Vanguard 1

Artist's rendition of Vanguard 1 in orbit. | |

| Mission type | Earth science |

|---|---|

| Operator | U.S. Navy |

| Harvard designation | 1958 Beta 2 |

| COSPAR ID | 1958-002B |

| SATCAT no. | 00005 |

| Mission duration | ~2,200 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Naval Research Laboratory |

| Launch mass | 1.47 kilograms (3.2 lb) |

| Dimensions | 6.4 inches (16 cm) diameter |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | March 17, 1958, 12:15:41 UTC |

| Rocket | Vanguard TV-4 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-18A |

| End of mission | |

| Last contact | May 1964 |

| Decay date | Est. 2198 (240-year orbital lifetime) |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Medium Earth |

| Semi-major axis | 8,619 kilometers (4,654 nmi)[1] |

| Eccentricity | 0.1846373[1] |

| Perigee | 657.3 kilometers (354.9 nmi)[1] |

| Apogee | 3,840.3 kilometers (2,073.6 nmi)[1] |

| Inclination | 34.3 degrees[1] |

| Period | 132.7 minutes[1] |

| RAAN | 124.3 degrees[1] |

| Argument of perigee | 229.0 degrees[1] |

| Mean anomaly | 113.6 degrees[1] |

| Epoch | August 23, 2018[1] |

| Revolution no. | +235,000[2] |

Vanguard 1 (ID: 1958-Beta 2 [3]) was the fourth artificial Earth orbital satellite to be successfully launched (following Sputnik 1, Sputnik 2, and Explorer 1). Vanguard 1 was the first satellite to have solar electric power.[4] Although communication with the satellite was lost in 1964, it remains the oldest man-made object still in orbit, together with the upper stage of its launch vehicle. It was designed to test the launch capabilities of a three-stage launch vehicle as a part of Project Vanguard, and the effects of the space environment on a satellite and its systems in Earth orbit. It also was used to obtain geodetic measurements through orbit analysis. Vanguard 1 was described by the Soviet Premier, Nikita Khrushchev, as "the grapefruit satellite".[5]

Spacecraft design

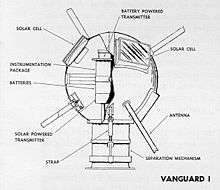

The spacecraft is a 1.47 kg (3.2 lb) aluminum sphere 16.5 cm (6.4 inches) in diameter. It contains a 10 mW, 108 MHz transmitter powered by a mercury battery and a 5 mW, 108.03 MHz[6] transmitter that was powered by six solar cells mounted on the body of the satellite. Six short antennas protrude from the sphere. The transmitters were used primarily for engineering and tracking data, but were also used to determine the total electron content between the satellite and the ground stations. Vanguard also carries two thermistors which measured the interior temperature over sixteen days in order to record the effectiveness of the thermal protection.

A backup version of Vanguard 1 is on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.[7]

Mission

On March 17, 1958, the three-stage launch vehicle placed Vanguard into a 654-by-3,969-kilometer (353 nmi × 2,143 nmi), 134.2 minute elliptical orbit inclined at 34.25 degrees. Original estimates had the orbit lasting for 2,000 years, but it was discovered that solar radiation pressure and atmospheric drag during high levels of solar activity produced significant perturbations in the perigee height of the satellite, which caused a significant decrease in its expected lifetime to only about 240 years.[8] Vanguard 1 transmitted its signals for nearly seven years as it orbited the Earth.[9]

Radio beacon

A 10 mW transmitter, powered by a mercury battery, on the 108 MHz band used for International Geophysical Year (IGY) scientific satellites, and a 5 mW, 108.03 MHz[10] transmitter powered by six solar cells were used as part of a radio phase-comparison angle-tracking system. The tracking data were used to show that the shape of the Earth has a very slight[11] north-south asymmetry, occasionally described as "pear-shaped" with the stem at the North Pole. These radio signals were also used to determine the total electron content between the satellite and selected ground-receiving stations.[8] The battery-powered transmitter provided internal package temperature for about sixteen days and sent tracking signals for twenty days. The transmitter powered by solar cells transmitted for more than six years. Its signal gradually weakened and was last received at Quito, Ecuador, in May 1964. Since then the spacecraft has been tracked optically from Earth, via telescope.[8]

Satellite drag atmospheric density

Because of its symmetrical shape, Vanguard 1 was used by experimenters for determining upper atmospheric densities as a function of altitude, latitude, season, and solar activity. As the satellite continuously orbited, it would deviate from its predicted positions slightly, accumulating greater and greater shift due to drag of the residual atmosphere. By measuring the rate and timing of orbital shifts, together with the body's drag properties, the relevant atmosphere's parameters could be back-calculated. It was determined that atmospheric pressures, and thus drag and orbital decay, were higher than anticipated, since Earth's upper atmosphere does taper off into space gradually.

This experiment was planned extensively prior to launch. Initial Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) proposals for the project included conical satellite bodies; this eliminated the need for a separate fairing and ejection mechanisms, and their associated weight and failure modes. Radio tracking would gather data and establish a position. Early in the program, optical tracking (with a Baker-Nunn camera network and human spotters) was added. A panel of scientists proposed changing the design to spheres, at least twenty inches in diameter and hopefully thirty. A sphere would have a constant optical reflection, and constant coefficient of drag, based on size alone, while a cone would have properties that varied with its orientation. James Van Allen of the University of Iowa proposed a cylindrical satellite based on his work with rockoons, which became Explorer 1, the first American satellite. The Naval Research Laboratory finally accepted a sphere with a 6.4-inch diameter as a "test vehicle", with a diameter of twenty inches set for the follow-on satellites. The weight savings, from reduced size as well as decreased instrumentation in the early satellites, was considered to be acceptable.

Since three of the Vanguard satellites are still orbiting 23 October 2018 with their drag properties essentially unchanged, they form a baseline data set on the atmosphere of Earth that is over 50 years old and continuing.[13][14][15]

After the mission

After its scientific mission ended in 1964, Vanguard 1 became a derelict object—just like the upper stage of the rocket used to launch the satellite had after it finished the delta-v maneuver to place Vanguard 1 in orbit in 1958. As of April 2018, both objects remain in orbit.[13][16]

50th anniversary

The Vanguard 1 satellite and upper launch stage hold the record for being in space longer than any other man-made object.[17][18]

A small group of former NRL and NASA workers had been in communication with one another, and a number of government agencies were asked to commemorate the event. The Naval Research Laboratory commemorated the event with a day-long meeting at NRL on March 17, 2008.[19] The meeting concluded with a simulation of the satellite's track as it passed into the orbital area visible from Washington, D.C., (where it is visible from the Earth's surface). The National Academy of Sciences scheduled some seminars to mark the 50th anniversary of the International Geophysical Year, which were the only official observances known.[20]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Vanguard 1 Satellite details 1958-002B NORAD 00005". N2YO. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "Vanguard 1, Oldest Manmade Satellite, Turns 60 This Weekend". AmericaSpace. Ben Evans. March 18, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ↑ "U.S. Space Objects Registry". Archived from the original on 2013-10-06. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ↑ Vanguard I the World's Oldest Satellite Still in Orbit Archived 2015-03-21 at the Wayback Machine., accessed September 24, 2007

- ↑ "Vanguard I - the World's Oldest Satellite Still in Orbit". Spacecraft Engineering Department, U.S. Navy. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19.

- ↑ "Project Vanguard Report No. 23 Minitrack Report No. 3, Receiver System". dtic.mil. Archived from the original on 2011-08-23.

- ↑ "Satellite, Vanguard 1, Backup". si.edu. Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Vanguard 1". NASA. Archived from the original on 2012-05-11. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Alfred. "A record of NASA space missions since 1958". NASA. NASA Technical Reports Server. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Sounds from the First Satellites". AMSAT. 2006-12-15. Archived from the original on 2008-03-12. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ↑ "Asimov - The Relativity of Wrong". tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-06-23.

- ↑ "Vanguard 1". NASA NSSDC. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15.

- 1 2 "Vanguard 1 - Satellite Information". Satellite database. Heavens-Above. Archived from the original on 2018-01-14. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- ↑ "Vanguard 2 - Satellite Information". Satellite database. Heavens-Above. Archived from the original on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Vanguard 3 - Satellite Information". satellite database. Heavens-Above. Archived from the original on 2013-09-25. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Vanguard 1 Rocket - Satellite Information". Satellite database. Heavens-Above. Archived from the original on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- ↑ Hollingham, Richard. "The world's oldest scientific satellite is still in orbit". Archived from the original on 2017-10-07.

- ↑ Lance K. Erickson (2010). Space Flight: History, Technology, and Operations. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-86587-419-0.

- ↑ "Vanguard I celebrates 50 years in space". EurekAlert!. 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Vanguard Approaches Half A Century In Space, Space Ref Interactive, by Keith Cowing, November 4, 2007