UN mediation of the Kashmir dispute

The United Nations has played an important role in maintaining peace and order in Jammu and Kashmir soon after the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, when a dispute erupted between the two States on the question of Jammu and Kashmir. India took this matter to the UN Security Council, which passed resolution 39 (1948) and established the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) to investigate the issues and mediate between the two countries. Following the cease-fire of hostilities, it also established the United Nations Military Observer Group for India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) to monitor the cease-fire line.

Overview

Following the outbreak of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, India's Governor General Mountbatten flew to Lahore On 1 November 1947 for a conference with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, proposing that, in all the princely States where the ruler did not accede to a Dominion corresponding to the majority population (which would have included Junagadh, Hyderabad as well Kashmir), the accession should be decided by an `impartial reference to the will of the people'. Jinnah rejected the offer.[1] The Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan met again in December, where Nehru informed Khan of India's intention to refer the dispute to the United Nations under article 35 of the UN Charter, which allows the member states to bring to the Security Council attention situations `likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace'.[2]

India sought resolution of the issue at the UN Security Council on 1 January 1948.[3] Following the set-up of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP), the UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on 21 April 1948. The measure imposed an immediate cease-fire and called on the Government of Pakistan 'to secure the withdrawal from the state of Jammu and Kashmir of tribesmen and Pakistani nationals not normally resident therein who have entered the state for the purpose of fighting.' It also asked Government of India to reduce its forces to minimum strength, after which the circumstances for holding a plebiscite should be put into effect 'on the question of Accession of the state to India or Pakistan.' However, it was not until 1 January 1949 that the ceasefire could be put into effect, signed by General Gracey on behalf of Pakistan and General Roy Bucher on behalf of India.[4] However, both India and Pakistan failed to arrive at a truce agreement due to differences over interpretation of the procedure for and the extent of demilitarisation. One sticking point was whether the Azad Kashmiri army was to be disbanded during the truce stage or at the plebiscite stage.[5]

The UNCIP made three visits to the subcontinent between 1948 and 1949, trying to find a solution agreeable to both India and Pakistan.[6] It reported to the Security Council in August 1948 that "the presence of troops of Pakistan" inside Kashmir represented a "material change" in the situation. A two-part process was proposed for the withdrawal of forces. In the first part, Pakistan was to withdraw its forces as well as other Pakistani nationals from the state. In the second part, "when the Commission shall have notified the Government of India" that Pakistani withdrawal has been completed, India was to withdraw the bulk of its forces. After both the withdrawals were completed, a plebiscite would be held.[7] The resolution was accepted by India but effectively rejected by Pakistan.[note 1]

The Indian government considered itself to be under legal possession of Jammu and Kashmir by virtue of the accession of the state. The assistance given by Pakistan to the rebel forces and the Pakhtoon tribes was held to be a hostile act and the further involvement of the Pakistan army was taken to be an invasion of Indian territory. From the Indian perspective, the plebiscite was meant to confirm the accession, which was in all respects already complete, and Pakistan could not aspire to an equal footing with India in the contest.[8]

The crux of India's argument, which it felt the UN Security Council had ignored, that Pakistan was an aggressor in a territory which had legally become part of India by the Instrument of Accession, has been criticized. The point is raised that the refusal of India to accept the accession of Junagadh's Muslim ruler to Pakistan must be taken into consideration when India raises such legalistic arguments.[9][10] Korbel points out that by agreeing to the Commission's resolutions as a basis for solving the dispute, India no longer has the right to use arguments such as ″Pakistani aggression″.[11]

The Pakistan government held that the state of Jammu and Kashmir had executed a Standstill Agreement with Pakistan which precluded it from entering into agreements with other countries. It also held that the Maharaja had no authority left to execute accession because his people had revolted and he had to flee the capital. It believed that the Azad Kashmir movement as well as the tribal incursions were indigenous and spontaneous, and Pakistan's assistance to them was not open to criticism.[12]

In short, India required an asymmetric treatment of the two countries in the withdrawal arrangements regarding Pakistan as an `aggressor', whereas Pakistan insisted on parity. The UN mediators tended towards parity, which was not to India's satisfaction.[13] In the end, no withdrawal was ever carried out, India insisting that Pakistan had to withdraw first, and Pakistan contending that there was no guarantee that India would withdraw afterwards.[14] No agreement could be reached between the two countries on the process of demilitarisation.[note 2]

Scholars have commented that the failure of the Security Council efforts of mediation owed to the fact that the Council regarded the issue as a purely political dispute without investigating its legal underpinnings.[note 3] Declassified British papers indicate that Britain and US have let their cold war calculations influence their policy in the UN disregarding the merits of the case.[note 4]

Stages of the UN involvement

McNaughton proposals

In December 1949 the Security Council asked its Canadian President General McNaughton to meet both sides for a solution. McNaughton forwarded his proposals to both Governments on 22 December and reported to the Security Council on 29 December, before his term as President of the Security Council expired on the 31st. Nevertheless, he continued his mediatory activities at the Council's request and submitted a final report on 3 February 1950.[15]

On 22 December he proposed that there be a simultaneous withdrawal of Pakistan's regular forces and India's regular forces not required for security, that there be a disbanding of both the Azad Kashmir forces and the Kashmir State forces and millitia and thirdly the inclusion of the Northern Areas in this demilitarisation scheme while the civil administration there would continue to be vested in the local authorities subject to United Nations supervision. Pakistan accepted these proposals but India rejected them.[16][17]

India was unhappy that Pakistan was treated as an equal party as in its view Pakistan was present illegally in Kashmir while India was present legally. The United States warned India that if it refused the McNaughton proposals it would be the third consecutive time it rejected the findings of an impartial UN agent and the United States would be left with no choice but to support whatever action the Security Council would take. Nehru responded by accusing the United States of pressuring the Indian Government. US policy makers saw India's rejection of the proposals as the "worst example yet" of its intransigence.[18][19]

Cold War historian Robert J. McMahon states that American officials increasingly blamed India for rejecting various UNCIP truce proposals under various dubious legal technicalities just to avoid a plebiscite. McMahon adds that they were 'right' since a Muslim majority made a vote to join Pakistan the 'most likely outcome' and postponing the plebiscite would serve India's interests. Some Indian officials privately admitted to their American counterparts that they would prefer a partition of the State to a plebiscite.[20]

US ambassador Loy Henderson told Indian officials that the American impression that India was evading a plebiscite was being fuelled by India's refusal to have a conciliatory attitude which would help in the prompt holding of a plebiscite.[21]

Despite India's rejection the McNaughton proposals were warmly received by the Security Council. It passed a resolution giving both countries five months to arrange the demilitarisation scheme. India later accepted the draft resolution on 14 March 1950. The Council then appointed Sir Owen Dixon who was to implement McNaughton's demilitarisation proposals for the State.[22][23][24]

Dixon Mission

In the first phase, Dixon proposed that areas evacuated by Pakistani troops could be administered by local authorities under the Commission's surveillance. To meet India's objections regarding the terms 'authorities' and 'surveillance' Dixon proposed that the administration in areas west to the ceasefire line be carried out according to the law and custom of the Jammu and Kashmir State before the present troubles. An officer of the United Nations would be attached to each district magistrate to ensure the impartiality required for the holding of a plebiscite. India refused this plan because it believed that the local authorities, who had replaced the 'legally authorised' State executives, were biased in favour of Pakistan and this was not in India's interests. India suggested no alternative.[25]

Dixon also believed that on the Indian side of the ceasefire line certain conditions needed to be met to ensure a fair plebiscite. This included attaching a United Nations officer with each district magistrate who would be allowed to see the Magistrate's records and proceedings, the UN officer was to observe, inspect, remonstrate and report. Nehru objected to these proposals on the grounds that they constituted a "derogation from the sovereignty of the state". Nehru also gave no alternative proposal.[26]

Sir Owen Dixon then put before the Prime Ministers of the two countries an alternative set of plans which would practically in the process eliminate the ceasefire line. These plans included a coalition government between Sheikh Abdullah and Ghulam Abbas, or allocating portfolios among the different parties. The second suggestion was instituting a neutral government by respected non-political persons for a period of six months before the plebiscite would take place. The membership would be equally split between Hindus and Muslims under a United Nations supervisor. The third proposal was the installation of an administrative body manned totally by UN representatives. None of these proposals appealed to Nehru.[27] Sir Owen Dixon took India to task in very strong language for its negative reactions to the various alternative demilitarisation proposals.[28]

Dixon next asked Nehru in the presence of the Pakistani Prime Minister whether it would be advisable to have plebiscites by region and allocate each region according to the results of a plebiscite in each. India reacted favourably to this plan.[29] According to the Indian commentator Raghavan, it was first Nehru who proposed a partition-cum-plebiscite plan: Jammu and Ladakh would go to India, Azad Kashmir and Northern Areas to Pakistan, and a plebiscite would be held in the Kashmir Valley. Dixon favoured the plan, which bears his name till this day.[30] Dixon agreed that people in Jammu and Ladakh were clearly in favour of India; equally clearly, those in Azad Kashmir and the Northern Areas wanted to be part of Pakistan. This left the Kashmir Valley and 'perhaps some adjacent country' around Muzaffarabad in uncertain political terrain. However, according to Dixon, Pakistan "bluntly rejected" the proposal. It believed that the plebiscite should be held in the entire state or the state should be partitioned along religious lines.[31] Pakistan believed that India's commitment to a plebiscite for the whole of Jammu and Kashmir should not be departed from.[32][33][34]

Dixon also had concerns that the Kashmiris, not being high-spirited people, may vote under fear or improper influences.[35] Following Pakistan's objections, he proposed that Sheikh Abdullah administration should be held in "commission" (in abeyance) while the plebiscite was held. This was not acceptable to India.[37] According to Raghavan, at this point, Dixon lost patience and declared failure.[30]

The Dixon Plan had involved the exclusion of both Indian and Pakistani troops from the plebiscite zone. On 16 August 1950 Nehru turned down Dixon's plan for a limited plebiscite on the grounds that the State Government's authority should not be suppressed for any period of time. Another reason for India's rejection of the Dixon Plan was that it wanted Indian troops to remain during the plebiscite for "security reasons" while it demanded at the same time that Pakistani troops be excluded.[38]

Dixon felt that India would not agree to demilitarisation and other provisions governing the plebiscite that guard against influence and abuse.[39][40] Without a demilitarisation by India, Pakistan and the Azad forces were not willing to withdraw from the territory they had retained. Dixon's final comment was to suggest that India and Pakistan be left to solve the situation on their own.[41]

Dixon's failure compounded American ambassador Loy Henderson's suspicions about India's motives and good faith. He concluded that Indian allegations of America's pro-Pakistan bias, which he noted were being quietly stimulated by Nehru himself, made it more suitable for the Commonwealth nations to intervene. Washington heeded its ambassador's advice and for the rest of 1950 played a scant role in the Kashmir issue.[42] Henderson became the first American to visit Kashmir and observed that the majority of the Valley would choose Pakistan over India in a plebiscite. The majority if given the third option would opt for independence.[43]

Frank Graham's mediation

When Dixon's successor, Dr Frank Graham, arrived in the subcontinent during a time of tension, he tried to effect demilitarisation prior to a plebiscite but India and Pakistan could not agree on the number of troops who were to remain in Kashmir.[44]

Dr Frank Graham was appointed by the Security Council as the UN representative for India and Pakistan on 30 April 1951. Dr Graham arrived in the subcontinent on 30 June 1951. The Graham mission had to reach an agreement between the two countries concerning the demilitarisation of Kashmir. Similar to the experience of previous UN envoys, Graham had first suggested a demilitarisation plan which found acceptance from Pakistan but rejection from India. Thereafter, Graham gave an alternative proposal whereby both countries were to gradually reduce their forces to a minimum and in proportion to the forces of both countries that were in Kashmir on 1 January 1949. This proposal was accepted by Pakistan but rejected by India.[45]

On 16 July 1952 Dr Graham offered a fresh set of proposals. By them Pakistan would reduce its forces to a size between 3,000 and 6,000 and India would reduce its troops number to between 12,000 and 16,000. But these figures did not include the state militias on the Indian side or the Gilgit and Norther Scouts in the Pakistani side. Because Pakistan was hopeful for a plebiscite it accepted this plan but India rejected it, possibly because the question of irregular forces was not solved. Graham revised the figures so that 6,000 would be the limit of Pakistan's forces and 18,000 would be the limit for India's forces. India answered by asking that it be allowed to keep 21,000 troops including the state militia in its side but that Pakistan be allowed only a civilian force of 4,000. Dr Graham reported his failure to the Security Council, which subsequently passed a resolution in December 1951 calling for India and Pakistan to come to an agreement on reducing the size of their forces. The resolution suggested Pakistan to cut the number of its troops to between 3,000 and 6,000 and India to cut its own troop numbers to a number between 12,000 and 18,000. The Security Council urged both countries to consider DR Graham's criterion for troop reductions Graham had suggested on 4 September 1951. Pakistan accepted this Security Council resolution but India rejected it and gave no reason for its rejection.[46]

Graham then tried to move the mediation further and, without proposing a corresponding increase of the Pakistani force size, gave a proposal which would allow India to keep 21,000 troops in Kashmir as had been India's demand. This proposal was also unsuccessful. Dr Graham submitted a second report to the United Nations in December to recount the failure of his attempts to achieve a demilitarisation for a plebiscite. His third submission to the UN in April 1952 reported some progress on the demilitarisation question as both countries had begun withdrawing forces since March. But by the fourth report in October 1952 Graham had to inform the Security Council that the talks had stumbled again over the question of the number and character of forces to be allowed on both sides. The Security Council then passed a resolution asking that the countries negotiate directly on this question. These negotiations took place in Geneva in February 1953 but it became obvious to the UN representative that this approach would be unsuccessful. Dr Graham submitted his final report on 27 March 1953 and his mediatory efforts ended. The two questions during this mediation which India and Pakistan differed upon was the number of forces to remain after demilitarisation on each side and when the plebiscite administrator could assume their duty.[47]

United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan

The Security Council Resolution 47 (1948) also enlarged the membership of the UNCIP to 5 members. India and Pakistan signed the Karachi Agreement in March 1951 and established a ceasefire line to be supervised by observers. After the termination of the UNCIP, the Security Council passed Resolution 91 (1951) and established a United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) to observe and report violations of ceasefire.

After the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the two countries signed the Simla Agreement in 1972 to define the Line of Control in Kashmir. India and Pakistan disagree on UNMOGIP’s mandate in Kashmir because India argued that the mandate of UNMOGIP has lapsed after the Simla agreement because it was specifically established to observe ceasefire according to the Karachi Agreement.

However, The Secretary General of the United Nations maintained that the UNMOGIP should continue to function because no resolution has been passed to terminate it. The military authorities of Pakistan have continued to lodge complaints with the UNMOGIP about ceasefire violations. The military authorities of India have lodged no complaints since January 1972 and have restricted the activities of the UN observers on the Indian side of the Line of Control.[48][49]

Map issues

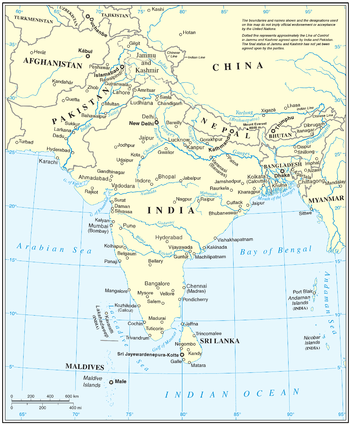

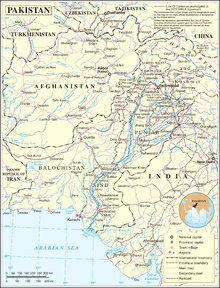

Map of UN's version of the South Asia region

Map of UN's version of the South Asia region

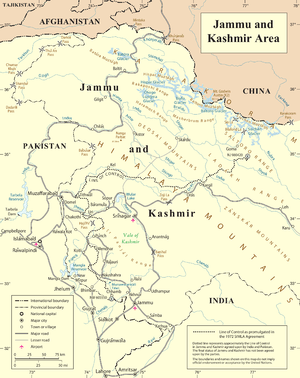

Map of UN's version of the Kashmir region

Map of UN's version of the Kashmir region_-_IND_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) Map of UN's version of the Republic of India and border areas

Map of UN's version of the Republic of India and border areas

As with other disputed territories, each government issues maps depicting their claims in Kashmir as part of their territory, regardless of actual control. It is illegal in India to exclude all or part of Kashmir in a map. It is also illegal in Pakistan not to include the state of Jammu and Kashmir as disputed territory, as permitted by the U.N. Non-participants often use the Line of Control and the Line of Actual Control as the depicted boundaries, as is done in the CIA World Factbook, and the region is often marked out in hashmarks, although the Indian government strictly opposes such practices . When Microsoft released a map in Windows 95 and MapPoint 2002, a controversy was raised because it did not show all of Kashmir as part of India as per Indian claim. However, all the neutral and Pakistani companies claim to follow UN's map and over 90% of all maps containing the territory of Kashmir show it as disputed territory.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Korbel (1953, p. 502): "Though India accepted the resolution, Pakistan attached to its acceptance so many reservations, qualifications and assumptions as to make its answer `tantamount to rejection'.

- ↑ Korbel (1953, pp. 506–507): "When a further Security Council resolution urged the governments of India and Pakistan to agree within thirty days on the demilitarization of Kashmir, on the basis of Dr. Graham's recommendation, Pakistan once more accepted and India once more refused....Dr. Graham met the Indian request for retaining in Kashmir 21,000 men, but continued to propose 6,000 soldiers on the Azad side. Pakistan could not accept the first provision and India continued to insist on its stand concerning the Azad forces. The meeting, which ended in failure, was accompanied by bitter comments in the newspapers of both India and Pakistan about United Nations intervention in the Kashmir dispute."

- ↑

- Korbel (1953, p. 507): "With the hindsight of six years, the Council's approach, though impartial and fair, appears to have been inadequate in that it did not reflect the gravity of the Kashmir situation.... The Security Council did not deal with either of these arguments [India's assumption of the legal validity of the accession and Pakistan's refusal to recognize its validity]. Nor did it consider the possibility of asking the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion on the juridical aspect of the conflict under Article 96 of the Charter. Nor did it invoke any provisions of Chapter VII of the Charter, which deals with `acts of aggression'."

- Subbiah (2004, p. 180): "From the beginning, the Security Council framed the problem as primarily a political dispute rather than looking to a major legal underpinning of the dispute: the Instrument of Accession's validity or lack thereof."

- ↑

- Ankit (2013, p. 276): To Cadogan [Britain's permanent representative at the UN], irrespective of “whether forces in question are organised or disorganised or whether they are controlled by, or enjoy the convenience of, Government of Pakistan,” India was entitled to take measures for self-defence: repelling invaders, pursuing invaders into Pakistan under Article 51 of the UN Charter and charging Pakistan as aggressor under Article 35.

- Ankit (2013, p. 279): Mountbatten, too, pleaded directly with Attlee along political as well as personal lines: "I am convinced that this attitude of the United States and the United Kingdom is completely wrong and will have far reaching results. Any prestige I may previously have had with my Government has of course been largely lost by my having insisted that they should make a reference to the United Nations with the assurance that they would get a square deal there."

References

- ↑ Noorani 2014, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Schofield 2003, pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Wellens, Karel (1990), Resolutions and Statements of the United Nations Security Council: (1946 - 1989) ; a Thematic Guide, BRILL, pp. 322–, ISBN 0-7923-0796-8

- ↑ Schofield 2003, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ "Plebiscite Conundrum". Kashmirlibrary.org. 5 January 1949. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Schofield 2003, p. 70.

- ↑ Varshney 1992, p. 211.

- ↑ Schofield 2003, pp. 70-71.

- ↑ Howley, James (1991). "Alive and Kicking: The Kashmir Dispute Forty Years Later". Penn State International Law Review. 9 (1): 96.

Indian commentators emphasize the legality of India's acts, condemning Pakistan for the use of force and coercion. However, such arguments must be viewed with an eye on India's overall conduct. Junagadh, one of the three Indian states which had not determined their future at the time of partition, consisted of a Hindu majority ruled by a Moslem dynasty. Here, India rejected the Moslem ruler's decision to accede to Pakistan

- ↑ Howley, James (1991). "Alive and Kicking: The Kashmir Dispute Forty Years Later". Penn State International Law Review. 9 (1): 97.

Indian commentators brand Pakistan as the aggressor in Kashmir, using force and coercion to usurp the territory. But here again, India's claims must be considered in context with its words and deeds elsewhere. India's treatment of Junagadh and Hyderabad must be considered in viewing Pakistan's actions in Kashmir and its claim of anticipatory self-defense

- ↑ Josef Korbel (8 December 2015). Danger in Kashmir. Princeton University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-1-4008-7523-8.

India again based her whole stand on Kashmir upon the conviction that Kashmir was already a part of India, against which Pakistan had been an aggressor. She expressed thorough indignation that this important fact had been ignored by the Security Council, by the Commission, and by Sir Owen Dixon. This was not quite the fact, of course; both the resolution of the Commission and the recommendation of Sir Owen Dixon had given concrete expression to its disapproval of the Pakistani army's presence on Kashmir. On the other hand, if India felt so strongly that the aggressiveness of Pakistan in Kashmir was the heart of the dispute, why had she not asked the Security Council to deal with it according to Chapter VII of the Charter, which is concerned with 'Acts of Aggression'? Why had she invoked only Chapter VI concerning 'Pacific Settlements of Disputes'? This may, of course, have been a serious error in political judgement on her part which she was now attempting to correct. But it is highly questionable whether, having decided to follow one procedure, India could now legitimately insist that the Security Council could proceed only on the basis of the assumption of Pakistan's 'act of aggression.' But finally, and it would appear decisively, India had already accepted as the basis for the solution of the Kashmir dispute the Commission's resolutions which contained no direct condemnations of Pakistan, and by so doing had forfeited the right to fall back on such arguments as Pakistani 'aggression.'

- ↑ Schofield 2003, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ Schofield 2003, pp. 82-85.

- ↑ Varshney 1992, p. 212.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. pp. 153–155. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. p. 154. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

Mr. McNaughton submitted the following proposals on 22 December for their consideration: First, the withdrawal of the regular forces of Pakistan and of the regular forces of India, not required for security, law and order, should be undertaken simultaneously. Next, the armed forces of the two halves of Kashmir were to be reduced by disbanding and disarming the Azad Kashmir forces on the one hand, and Kashmir State forces and militia on the other. Thirdly, the Northern Areas were to be brought within this scheme of demilitarization, but there the civil administration should continue to be vested in the local authorities subject to the supervision of the United Nations. India suggested two far reaching amendments to the proposals and thus rejected them by implication. It was her view that only the Azad Kashmir forces were to be disbanded and disarmed. She also held that the defence of the Northern Areas should revert to India and their civil administration to the Kashmir State Government. Pakistan accepted these proposals with minor modifications.

- ↑ Victoria Schofield (30 May 2010). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-85773-078-7.

General A. G. L. McNaughton, the Canadian president of the Security Council, was appointed as an 'informal mediator' in order to establish a plan for demilitarisation prior to the holding of a plebiscite. Although Pakistan agreed to his proposals, India did not.

- ↑ Robert J. McMahon (1 June 2010). The Cold War on the Periphery: The United States, India, and Pakistan. Columbia University Press. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-231-51467-5.

He urged India to reconsider its position and noted rather pointedly that if McNaughton's effort failed owing to India's rejection, it "will be [the] third consecutive time Ind[ia] has refused [to] accept findings [of an] impartial UN agent."

- ↑ Howard B. Schaffer (1 September 2009). The Limits of Influence: America's Role in Kashmir. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-8157-0370-9.

U.S. policymakers considered India's rejection the worst example yet of its intransigence

- ↑ Robert J. McMahon (1 June 2010). The Cold War on the Periphery: The United States, India, and Pakistan. Columbia University Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-231-51467-5.

- ↑ Howard B. Schaffer (1 September 2009). The Limits of Influence: America's Role in Kashmir. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-0-8157-0370-9.

The ambassador was characteristically forthright in his reply. He told Bajpai that U.S. officials' doubts about Indian intentions had been fueled by New Delhi's unwillingness to adopt the kind of conciliatory attitude that could help promote a prompt holding of the plebiscite.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

At the next meeting the Security Council appointed Sir Owen Dixon as the U.N. representative for India and Pakistan on 12 April 1950. He was to implement the McNaughton proposals for the demilitarization of the State.

- ↑ Josef Korbel (8 December 2015). Danger in Kashmir. Princeton University Press. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-1-4008-7523-8.

It called upon India and Pakistan 'to prepare and execute within a period of five months from the date of this resolution a programme of demilitarization on the basis of principles 2 of General McNaughton's proposal.; It further decided to replace the United Nations Commission by a representative entrusted with arbitrary powers 'to interpret the agreements reached by the parties for demilitarization,' in case they should agree in this most important matter. It also requested this representative to make any suggestions which would in his opinion expedite and offer an enduring solution to the Kashmir dispute.

- ↑ Victoria Schofield (30 May 2010). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-85773-078-7.

On 27 May 1950 the Australian jurist, Sir Owen Dixon, arrived in the sub-continent, as the one man successor to UNCIP...Patel wrote to Nehru that Dixon was working to bring about an agreement on the question of demilitarisation.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. p. 159. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

To meet the Indian objection and to resolve the uncertainties of terms like “local authorities” and “surveillance,” Sir Owen Dixon proposed that to the west of the cease-fire line the administration be carried on in accordance with the law and custom of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, as existing before the present troubles. An officer of the United Nations was to be attached to each District Magistrate or subordinate officer now holding power, to ensure the impartiality required for the organization of the plebiscite. The U.N. officer, exercising supervisory power, was to report his specific findings to the U.N. representative or his delegate for appropriate action. Although the plan was reportedly made to subserve the ends of justice and to demonstrate the sovereignty of the law of Jammu and Kashmir, India objected to the scheme on the ground that the existing local officials, who had replaced the legally authorised executives of the State, were biased in favour of Pakistan, and their contemplated retention would act against India's interests. No alternative plan was suggested by India.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. p. 159. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. p. 160. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

No alternative proposal was made. Sir Owen Dixon put before the two Prime Ministers alternative plans for the administration of the whole of Kashmir as a unit, eliminating in the process the cease-fire line. The first possibility was a coalition government of Abdullah and Ghulam Abbas, or allocation of portfolios among the different parties. The second suggestion was for the institution of a neutral government by non-political persons commanding respect and functioning for a specific period of six months before the plebiscite. The members would be equally divided between the Hindus and the Muslims, and a U.N. Chairman would supervise. The third plan would have installed an administrative body wholly manned by U.N. representatives. Dixon reported to the Council that none of these suggestions commended itself to the Prime Minister of India.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

He summed up his impressions in very strong language, sharply taking India to task for its negative attitude towards the various alternative demilitarization proposals.

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

- 1 2 Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India 2010, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Snedden, Christopher (2005), "Would a plebiscite have resolved the Kashmir dispute?", South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 28 (1): 64–86, doi:10.1080/0085640050005614

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

In any case, Pakistan turned down the proposal on the ground that India's commitment for a plebiscite in the whole of Jammu and Kashmir should not be departed from.

- ↑ Josef Korbel (8 December 2015). Danger in Kashmir. Princeton University Press. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-1-4008-7523-8.

India, Pakistan insisted, was committed to a plebiscite in the State of Jammu and Kashmir as a whole.

- ↑ Hilal, A.Z. (1997). "Kashmir dispute and UN mediation efforts: An historical perspective". Small Wars & Insurgencies. 8 (2): 75.

This time it was Pakistan who refused to accept his proposal, arguing that Pakistan considered it a breach of India's agreement that: 'The destination of the state....as a whole should be decided by a single plebiscite taken over the entire state'.

- ↑ Christopher Snedden (2005) Would a plebiscite have resolved the Kashmir dispute?, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 28:1, 75, DOI: 10.1080/00856400500056145

- ↑ Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, vol. 15, part I, p.227, quoted in Shankar, Nehru's Legacy in Kashmir 2016, p. 10

- ↑ Nehru asked Dixon, "What could be more advantageous to Pakistan, than to be able to say that they had “kicked out the Kashmir Government and the India Government from Kashmir…[that would be] patently ninety per cent of victory for Pakistan then and there, quite apart from the plebiscite."[36]

- ↑ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6.

Troops of both countries were to be excluded from the limited plebiscite area...On 16 August 1950 the Indian Prime Minister rejected the plan for limited plebiscite on the following grounds:...4)The security of the State necessitated the presence of Indian troops and the exclusion of the Pakistani troops from the plebiscite area. India would not depart from that principle. Sir Owen Dixon disagreed with the Indian position. He aired his views that a neutral administration was necessary for a fair plebiscite, that the exclusion of Indian troops...were essential prerequisites of the same.

- ↑ Bradnock, Robert W. (998), "Regional geopolitics in a globalising world: Kashmir in geopolitical perspective", Geopolitics, 3 (2): 11, doi:10.1080/14650049808407617,

More importantly, Dixon concluded that it was impossible to get India's agreement to any reasonable terms. 'In the end I became convinced that India's agreement would never be obtained to demilitarisation in any such form, or to provisions governing the period of the plebiscite of any such character, as would in my opinion permit of the plebiscite being conducted in conditions sufficiently guarding against intimidation and other forms of influence and abuse by which the freedom and fairness of the plebiscite might be imperilled.

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 83.

- ↑ Victoria Schofield (2000). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-1-86064-898-4.

Without such demilitarisation, the local 'Azad' and regular Pakistani forces were not prepared to withdraw from the territory they had retained.

- ↑ Howard B. Schaffer (1 September 2009). The Limits of Influence: America's Role in Kashmir. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-8157-0370-9.

The failure of the Dixon mission seems to have sharpened even further Ambassador Henderson's already deep suspicions of Indian motives and good faith. He concluded that growing resentment in India about the allegedly pro-Pakistan attitude of the United States on Kashmir—which he reported had been quietly stimulated by Nehru himself-made it desirable to have Britain and other commonwealth countries take the lead in working out a solution...Washington appears to have heeded the ambassador's advice.

- ↑ Howard B. Schaffer (1 September 2009). The Limits of Influence: America's Role in Kashmir. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-8157-0370-9.

He found the military officers of the UN monitoring group and other foreigners in Kashmir almost unanimous in holding that the people of the Valley would prefer Pakistan to India if they had the opportunity to vote freely. Most thought that a majority would prefer independence if offered that option.

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 83-86.

- ↑ Hilal, A.Z. (1997). "Kashmir dispute and UN mediation efforts: An historical perspective". Small Wars & Insurgencies. 8 (2): 76.

However, like the previous UN envoys, Graham suggested a plan for demilitarisation of Kashmir which was accepted by Pakistan and again the Indian attitude was negative. India rejected his earlier plan and Graham proposed another plan which called for gradual reduction of the forces to a minimum and the troop withdrawal in proportion to the Indian and Pakistani forces present in Kashmir on 1 January 1949. Pakistan accepted this plan and Indian rejected it.

- ↑ Hilal, A.Z. (1997). "Kashmir dispute and UN mediation efforts: An historical perspective". Small Wars & Insurgencies. 8 (2): 77.

Pakistan was asked to cut the number of troops to between 3,000 and 6,000 and a range of 12,000 to 18,000 was suggested for Indian force. Both sides were urged to consider the criteria for reduction of forces suggested by Dr Graham in his proposals of 4 September 1952. Pakistan accepted this resolution but India rejected it without any justification and reason

- ↑ Hilal, A.Z. (1997). "Kashmir dispute and UN mediation efforts: An historical perspective". Small Wars & Insurgencies. 8 (2): 77.

- ↑ https://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unmogip/background.shtml

- ↑ Shucksmith, Christy; White, Nigel D. (2015), "United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP)", in Joachim Alexander Koops; Norrie MacQueen; Thierry Tardy; Paul D. Williams, The Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, Oxford University Press, pp. 139–, ISBN 978-0-19-968604-9

- Sources

- Ankit, Rakesh (2013), "Britain and Kashmir, 1948: "The Arena of the UN"", Diplomacy & Statecraft, 24 (2): 273–290, doi:10.1080/09592296.2013.789771, (Subscription required (help))

- Bose, Sumantra (2003). Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01173-2.

- Korbel, Josef (1953), "The Kashmir dispute after six years", International Organization, Cambridge University Press, 7 (4): 498–510, doi:10.1017/s0020818300007256, JSTOR 2704850, (Subscription required (help))

- Noorani, A. G. (2014) [first published in 2013 by Tulika Books], The Kashmir Dispute, 1947-2012, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-940018-8

- Panigrahi, D. N. (2009), Jammu and Kashmir, the Cold War and the West, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-51751-8

- Rai, Mridu (2004). Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 1850656614.

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

- Snedden, Christopher (2013) [first published as The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir, 2012], Kashmir: The Unwritten History, HarperCollins India, ISBN 9350298988

- Subbiah, Sumathi (2004), "Security Council Mediation and the Kashmir Dispute: Reflections on Its Failures and Possibilities for Renewal", Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, 27 (1): 173–185

- Varshney, Ashutosh (1992). "Three Compromised Nationalisms: Why Kashmir has been a Problem" (PDF). In Raju G. C. Thomas. Perspectives on Kashmir: the roots of conflict in South Asia. Westview Press. pp. 191–234. ISBN 978-0-8133-8343-9.