Tokyo Rose

Tokyo Rose (alternative spelling Tokio Rose) was a name given by Allied troops in the South Pacific during World War II to all female English-speaking radio broadcasters of Japanese propaganda.[1] The programs were broadcast in the South Pacific and North America to demoralize Allied troops abroad and their families at home by emphasizing troops' wartime difficulties and military losses.[1][2] Several female broadcasters operated under different aliases and in different cities throughout the Empire, including Tokyo, Manila, and Shanghai.[3] The name "Tokyo Rose" was never actually used by any Japanese broadcaster,[2][4] but it first appeared in U.S. newspapers in the context of these radio programs in 1943.[5]

During the war, Tokyo Rose was not any one individual, but rather a group of largely unconnected women working within the same propagandist effort throughout the Japanese Empire.[3] In the years shortly following the war, the figure of 'Tokyo Rose' – whom the FBI now avers to be "mythical" – became an important symbol of Japanese villainy for the United States.[1] American cartoons,[6][7] films,[8][9][10] and propaganda videos[11] between 1945 and 1960 tend to portray her as highly sexualized, manipulative, and deadly to American interests in the South Pacific, particularly by leaking intelligence of American losses in radio broadcasts. Similar accusations surround the propaganda broadcasts of Lord Haw-Haw[12] and Axis Sally,[13] and in 1949 the San Francisco Chronicle described Tokyo Rose as the "Mata Hari of radio."[14]

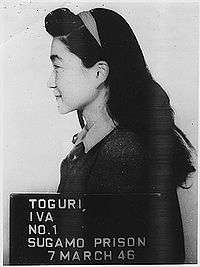

Tokyo Rose ceased to be merely a symbol in September 1945 when Iva Toguri D'Aquino, an American-born Japanese disc jockey for a propagandist radio program, attempted to return to the United States.[1] Toguri was accused of being the 'real' Tokyo Rose, arrested, tried, and became the seventh person in U.S. history to be convicted of treason.[1] Toguri was eventually paroled from prison in 1956, but it was more than 20 years before she received an official presidential pardon for her role in the war.[1]

Iva Toguri and The Zero Hour

Although she broadcast under the name "Orphan Ann," Iva Toguri has been known as "Tokyo Rose" since her return to the United States in 1945. An American citizen and the daughter of Japanese immigrants, Toguri traveled to Japan to tend to a sick aunt just prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.[15] Unable to leave the country when war broke out with the United States, unable to stay with her aunt's family as an American citizen, and unable to receive any aid from her parents who were placed in internment camps in Arizona, Toguri eventually took a job as a part-time typist at Radio Tokyo (NHK).[3] She was quickly recruited as a broadcaster for the 75-minute propagandist program The Zero Hour, which consisted of skits, news reports, and popular American music.[2]

According to studies conducted in 1968, of the 94 men who were interviewed and who recalled listening to The Zero Hour while serving in the Pacific, 89% recognized it as propaganda, and less than 10% felt "demoralized" by it.[2] 84% of the men listened because the program had "good entertainment," and one GI remarked, "[l]ots of us thought she was on our side all along."[2]

After World War II ended in 1945, the U.S. military detained Toguri for a year before releasing her for lack of evidence. Department of Justice officials agreed that her broadcasts were "innocuous".[16] But when Toguri tried to return to the United States, a popular uproar ensued because Walter Winchell (a powerful broadcasting personality) and the American Legion lobbied relentlessly for a trial, prompting the Federal Bureau of Investigation to renew its investigation[17] of Toguri's wartime activities. Her 1949 trial resulted in a conviction on one of eight counts of treason. In 1974, investigative journalists found that key witnesses claimed that they were forced to lie during testimony. U.S. President Gerald Ford pardoned Toguri in 1977.[1]

Tokyo Mose

Walter Kaner (May 5, 1920 – June 27, 2005) was a journalist and radio personality who broadcast under the name Tokyo Mose during and after World War II. Kaner aired on US Army Radio, at first to offer comic rejoinders to the propaganda broadcasts of Tokyo Rose and then as a parody to entertain U.S. troops abroad. In U.S.-occupied Japan, his "Moshi, Moshi Ano-ne" jingle was sung to the tune of "London Bridge is Falling Down" and became so popular with Japanese children and GIs that the army paper called it "the Japanese occupation theme song." In 1946, Elsa Maxwell referred to Kaner as "the breath of home to unknown thousands of our young men when they were lonely."[18]

Popular culture

Tokyo Rose has been the subject of songs, movies, and documentaries:

- 1945: Tokyo Woes, propaganda cartoon directed by Bob Clampett featuring Seaman Hook. The cartoon's titular character (voiced by an uncredited Sara Berner) is portrayed as an overly enthusiastic, crooked-toothed Japanese woman speaking on a propaganda broadcast with a loud voice and an American accent.[6]

- 1945: Tokyo Rose "Voice of Truth", five-minute film short produced by the U.S. Treasury Department to promote public support of the 7th war loan.[11]

- 1946: Tokyo Rose, film drama directed by Lew Landers.[8] Lotus Long played "Tokyo Rose", a "seductive jap traitress";[19] Byron Barr played the G.I. protagonist sent to kidnap her.

- 1949: In the musical "South Pacific", sailors mention getting "advice from Tokyo Rose" in the song "There is Nothin' Like a Dame".

- 1957: The Hollywood service comedy "Joe Butterfly", about U.S. military journalists in Japan just after World War II, includes a fictionalized subplot about the search for the "real" Tokyo Rose.

- 1957: In the film The Bridge on the River Kwai, a Tokyo Rose broadcast is briefly heard on the demolition team's portable radio.

- 1958: In the film Run Silent, Run Deep a Tokyo Rose broadcast detailed ships and sailors lost at sea based on information gained from trash jettisoned by U.S. submarines.[9]

- 1959: In the film Operation Petticoat a Tokyo Rose broadcast warns the crew of a U.S. submarine to surrender.

- 1969: The Story of "Tokyo Rose", CBS-TV and WGN radio documentary written and produced by Bill Kurtis.

- 1974: UK rock band Chapman Whitney Streetwalkers recorded a song called Tokyo Rose on their album Chapman Whitney Streetwalkers.

- 1976: Tokyo Rose, CBS-TV documentary segment on 60 Minutes.

- 1976: "Harbor Lights", a hit song by Boz Scaggs on his album Silk Degrees, begins with the line "Son of a Tokyo Rose, I was bound to wander from home".

- 1978: Dutch rock band Focus released a song entitled "Tokyo Rose" on their album Focus con Proby.

- 1985: Canadian rock band Idle Eyes had a Top 20 hit in their homeland with the song "Tokyo Rose" from their self-titled debut album. The song's narrator addresses his lover, saying she "tells a story like Tokyo Rose".

- 1987: American heavy metal band Shok Paris released the song "Tokyo Rose" on their 1987 album Steel and Starlight. It's about a lonely GI who fell in love with the propaganda broadcaster during the war, and remembers her voice many years later.[20]

- 1988: Canadian singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell mentions "Tokyo Rose on the radio" in her song "The Tea Leaf Prophecy (Lay Down Your Arms)" on the album Chalk Mark in a Rainstorm.

- 1989: American composer and musician Van Dyke Parks released a concept album titled Tokyo Rose, on the subject of American and Japanese relations.

- 1992: In season 7 episode 5 ("Where's Charlie?") of the American TV sitcom The Golden Girls: terminally naive Rose Nylund mistakenly believes her roommate Blanche Devereaux's beau has left Blanche for Tokyo Rose ...

- 1995: Tokyo Rose: Victim of Propaganda, A&E Biography documentary, hosted by Peter Graves, available on VHS (AAE-14023).

- 1997: the Vigilantes of Love released the song "Tokyo Rose" on their album Slow Dark Train.

- 2002: Japanese band Cali Gari released the song "Tokyo Rose au Monde Club" on their album Dai 7 Jikkenshitsu.

- 2010: In his dissent from Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310, 424 (2010) Justice Stevens remarked: "If taken seriously, our colleagues' assumption that the identity of a speaker has no relevance to the Government's ability to regulate political speech would lead to some remarkable conclusions. Such an assumption would have accorded the propaganda broadcasts to our troops by "Tokyo Rose" during World War II the same protection as speech by Allied commanders".

- 2011: American country-rockabilly band Whiskey Kill, released the song "Tokyo Rose", the opening track for their debut album Pissed Off Betty.[21]

See also

- Eastern Jewel – Chinese woman who spied for Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War

- Lord Haw-Haw – propagandist who broadcast from Nazi Germany during World War II

- Mildred Gillars – propagandist who broadcast from Nazi Germany during World War II

- Rita Zucca – propagandist who broadcast from Fascist Italy during World War II

- Mitsu Yashima – the American equivalent of Tokyo Rose[22]

- Radiostacja Wanda (Südstern Aktion) – Nazi Germany radio station broadcasting propaganda aimed at Polish II Corps fighting in the Italian Campaign (World War II)

- Pyongyang Sally – propagandist who broadcast from North Korea during the Korean War

- Hanoi Hannah – propagandist who broadcast from North Vietnam during the Vietnam War

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Iva Toguri d'Aquino and "Tokyo Rose"". Famous Cases & Criminals. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berg, Jerome S. The Early Shortwave Stations: A Broadcasting History Through 1945. Jefferson: McFarland, 2013. CREDO Reference. Web. Retrieved 5 March 2017. p.205.

- 1 2 3 Shibusawa, Naoko (2010). "Femininity, Race, and Treachery: How 'Tokyo Rose' Became a Traitor to the United States after the Second World War". Gender and History. 22:1: 169–88 – via Wiley Online LIbrary.

- ↑ Kushner, Barak. "Tokyo Rose." Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present. Ed. Nicholas John Cull, et al. 2003. Credo Reference. Accessed 05 Mar 2017.

- ↑ Arnot, Charles P. (June 22, 1943). "American Submarines Have Sunk 230 Japanese Ships in Pacific". Brainerd Daily Dispatch. p. 6.

We were tuned in on Radio Tokyo when Tokyo Rose, the woman who broadcasts in English, came on the air with "Hello America ... You build 'em, we sink 'em..."

- 1 2 Tokyo Woes (1945) on IMDb

- ↑ Leon Schlessinger, Tokyo Woes, retrieved 2017-05-22

- 1 2 Tokyo Rose (1946) on IMDb

- 1 2 Beach, Edward Latimer (1955). Run Silent, Run Deep. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 245–7. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ↑ Pfau, Ann Elizabeth (2008). "The Legend of Tokyo Rose". Miss Yourlovin: GIs, Gender, and Domesticity during World War II. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231509565.

- 1 2 Tokyo Rose "Voice of Truth" on YouTube

- ↑ Pfau, Ann Elizabeth; Householder, David (2009). "'Her Voice a Bullet': Imaginary Propaganda and the Legendary Broadcasters of World War II". In Strasser, Susan; Suisman, David. Sound in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ↑ Pfau, Ann; Hochfelder, David (April 24, 2008). "World War II Radio Propaganda: Real and Imaginary". Talking History.

- ↑ Stanton Delaplane, 'Tokyo Rose on Trial: "Bribery" Comes up, but it's Ruled out of Court', San Francisco Chronicle, 16 July 1949, p. 3.

- ↑ CriticalPast (2014-03-24), Iva Toguri D'Aquino (Iva Ikuko Toguri) reads propaganda from Radio Tokyo and talk...HD Stock Footage, retrieved 2017-03-06

- ↑ Pierce, J. Kingston (October 2002). "Tokyo Rose: They Called Her a Traitor". American History. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30.

- ↑ "FBI — Tokyo Rose". 2017-05-03. Archived from the original on 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ "Walter Kaner, Gazette Columnist, Foundation Head". Queens Gazette. June 29, 2005. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ↑ Tokyo Rose (Movie poster). Cleveland, Ohio: Morgan Litho. Corp. 1945.

- ↑ "Tokyo Rose-Shok Paris".

- ↑ "Whiskey Kill "Tokyo Rose" Live on Stay Tuned". Stay Tuned. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: WSCA 106.1FM. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ Stone, Judy (March 18, 2007). "An unlikely heroine of World War II". SFGate. Hearst Communications Inc.

Bibliography

- Duus, Masayo (1979). Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific (hardcover)

|format=requires|url=(help). New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-0870113543. - Howe, Russell Warren (1990). The Hunt for 'Tokyo Rose' (paperback)

|format=requires|url=(help). New York: Madison Books. ISBN 978-1568330136. - Kaelin, J. C., Jr. ""Orphan Ann" ("Tokyo Rose")". EarthStation1.com.

- "Iva Toguri [obituary]". The Telegraph. September 28, 2006. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tokyo Rose. |

- "Zero Hour" broadcasts archived at EarthStation1.com

- "Zero Hour" broadcast (excerpt) and commentary by Iva Toguri D'Aquino ("Orphan Ann") in 1945, at YouTube.com

- FBI file on Tokyo Rose at vault.fbi.gov

- "The Zero Hour" show 8-14-1944,[1] music with "Ann the Orphan," Iva Toguri D'Aquino, a Japanese-American dubbed "Tokyo Rose" by the American military

- "Tokyo Woes"- Voice of Mel Blanc (of Bugs Bunny fame) in this US Navy cartoon. Because they wanted to keep this a secret, all original negatives were destroyed shortly after release.

- ↑ Federal Communications Commission. Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service (1944-08-14), Zero Hour, 08-14-1944 (Tokyo Rose), retrieved 2017-05-14