Tokugawa Yoshinobu

| Prince Tokugawa Yoshinobu | |

|---|---|

| 徳川 慶喜 | |

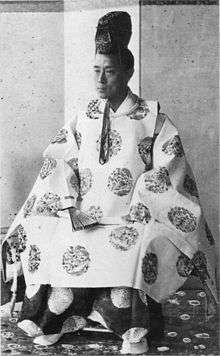

Tokugawa Yoshinobu as shōgun | |

| Shōgun | |

|

In office August 29, 1866 – November 19, 1867 | |

| Monarch | |

| Preceded by | Tokugawa Iemochi |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Member of the House of Peers | |

|

In office 1902–1910 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

October 28, 1837 Edo |

| Died |

November 22, 1913 (aged 76) Bunkyō |

| Resting place | Yanaka Cemetery |

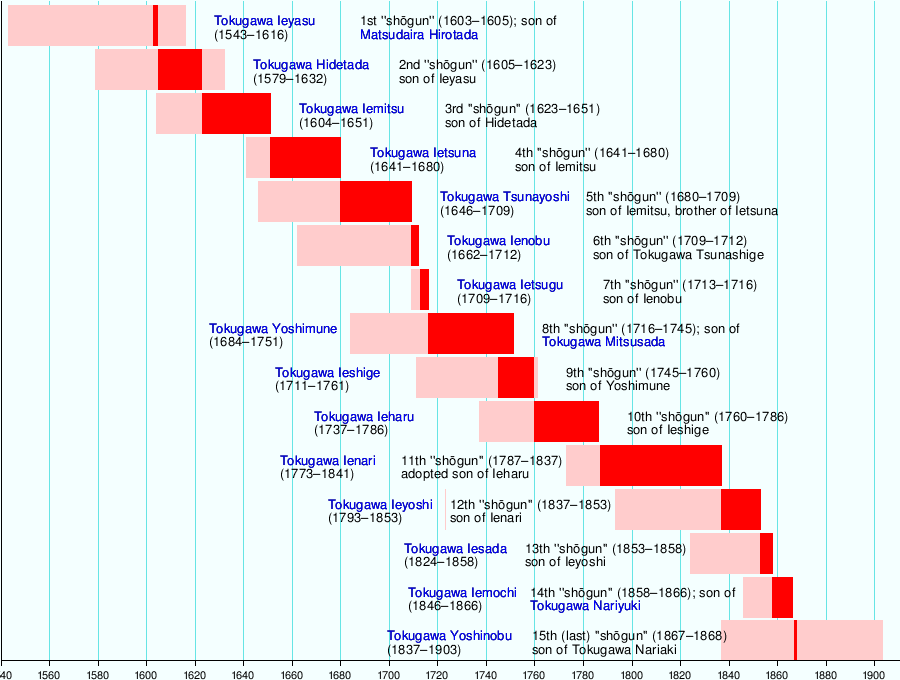

Prince Tokugawa Yoshinobu (徳川 慶喜, also known as Tokugawa Keiki; October 28, 1837 – November 22, 1913) was the 15th and last shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He was part of a movement which aimed to reform the aging shogunate, but was ultimately unsuccessful. After resigning in late 1867, he went into retirement, and largely avoided the public eye for the rest of his life.

Early life

Tokugawa Yoshinobu was born in Edo, as the seventh son of Tokugawa Nariaki, daimyō of Mito. Mito was one of the gosanke, the three branch families of the Tokugawa clan which were eligible to be chosen as shōgun. His birthname was Matsudaira Shichirōmaro (七郎麻呂)[1] His mother, Princess Arisugawa Yoshiko, was a member of the Arisugawa-no-miya, a cadet branch of the imperial family; through her, he was a third cousin (once removed) of the then Emperor, Ninkō. Shichirōmaro was brought up under strict, spartan supervision and tutelage.[2] While his father Nariaki respected the second Mito Tokugawa Mitsukuni who had sent off the second and younger sons from Edo to Mito to raise them, Shichirōmaro was seven months old when he arrived in Mito in 1838. He was taught in the literary and martial arts, as well as receiving a solid education in the principles of politics and government at Kōdōkan.[3]

At the instigation of his father, Shichirōmaro was adopted by the Hitotsubashi-Tokugawa family in order to have a better chance of succeeding to the shogunate[4] and changed his first name to Akimune(昭致). He became family head in 1847, coming of age that year, receiving court rank and title, and taking the name Yoshinobu.[5] Upon the death of the 13th shōgun, Iesada, in 1858, Yoshinobu was nominated as a potential successor.[6] His supporters touted his skill and efficiency in managing family affairs. However, the opposing faction, led by Ii Naosuke, won out. Their candidate, the young Tokugawa Yoshitomi, was chosen, and became the 14th shōgun Iemochi.[7] Soon after, during the Ansei Purge, Yoshinobu and others who supported him were placed under house arrest.[8] Yoshinobu himself was made to retire from Hitotsubashi headship.

The period of Ii's domination of the Tokugawa government was marked by mismanagement and political infighting. Upon Ii's assassination in 1860, Yoshinobu was reinstated as Hitotsubashi family head, and was nominated in 1862 to be the shōgun's guardian (将軍後見職 shōgun kōken-shoku), receiving the position soon afterwards.[9] At the same time, his two closest allies, Matsudaira Yoshinaga and Matsudaira Katamori, were appointed to other high positions: Yoshinaga as chief of political affairs (政治総裁職 seiji sōsai shoku),[10] Katamori as Guardian of Kyoto (京都守護職 Kyoto Shugoshoku).[11] The three men then took numerous steps to quell political unrest in the Kyoto area, and gathered allies to counter the activities of the rebellious Chōshū Domain. They were instrumental figures in the kōbu gattai political party, which sought a reconciliation between the shogunate and the imperial court.[12]

In 1864, Yoshinobu, as commander of the imperial palace's defense, defeated the Chōshū forces in their attempt to capture the imperial palace's Hamaguri Gate (蛤御門 Hamaguri-Gomon) in what is called the Kinmon Incident. This was achieved by use of the forces of the Aizu–Satsuma coalition.[13]

Shōgun (1866–1867)

After the death of Tokugawa Iemochi in 1866, Yoshinobu was chosen to succeed him, and became the 15th shōgun.[14] He was the only Tokugawa shōgun to spend his entire tenure outside of Edo: he never set foot in Edo Castle as shōgun.[15] Immediately upon Yoshinobu's ascension as shōgun, major changes were initiated. A massive government overhaul was undertaken to initiate reforms that would strengthen the Tokugawa government. In particular, assistance from the Second French Empire was organized, with the construction of the Yokosuka arsenal under Léonce Verny, and the dispatch of a French military mission to modernize the armies of the bakufu.[16]

The national army and navy, which had already been formed under Tokugawa command, were strengthened by the assistance of the Russians, and the Tracey Mission provided by the British Royal Navy. Equipment was also purchased from the United States.[17] The outlook among many was that the Tokugawa shogunate was gaining ground towards renewed strength and power; however, it fell in less than a year.

Boshin War (1868–69)

Fearing the renewed strengthening of the Tokugawa shogunate under a strong and wise ruler, samurai from Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa formed an alliance to counter it. Under the banner of sonnō jōi ("revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians!") coupled with a fear of the new shōgun as the "Rebirth of Ieyasu" (家康の再来) who would continue to usurp the power of the Emperor, they worked to bring about an end to the shogunate, though they varied in their approaches. In particular, Tosa was more moderate; it proposed a compromise whereby Yoshinobu would resign as shōgun, but preside over a new national governing council composed of various daimyōs. To this end, Yamanouchi Toyonori, the lord of Tosa, together with his advisor, Gotō Shōjirō, petitioned Yoshinobu to resign in order to make this possible.[18]

On November 9, 1867, Yoshinobu tendered his resignation to the Emperor and formally stepped down ten days later, returning governing power to the Emperor.[19] He then withdrew from Kyoto to Osaka. However, Satsuma and Chōshū, while supportive of a governing council of daimyōs, were opposed to Yoshinobu leading it.[18] They secretly obtained an imperial edict[18] calling for the use of force against Yoshinobu (later shown to be a forgery)[20] and moved a massive number of Satsuma and Chōshū troops into Kyoto.[21] There was a meeting called at the imperial court, where Yoshinobu was stripped of all titles and land,[22] despite having taken no action that could be construed as aggressive or criminal. Any who would have opposed this were not included in the meeting.[21] Yoshinobu opposed this action, and composed a message of protest, to be delivered to the imperial court;[23] at the urging of the leaders of Aizu, Kuwana, and other domains, and in light of the immense number of Satsuma and Chōshū troops in Kyoto, he dispatched a large body of troops to convey this message to the court.[24]

When the Tokugawa forces arrived outside Kyoto, they were refused entry, and were attacked by Satsuma and Chōshū troops, starting the Battle of Toba–Fushimi, the first clash of the Boshin War.[25] Though the Tokugawa forces had a distinct advantage in numbers, Yoshinobu abandoned his army in the midst of the fight once he realized the Satsuma and Chōshū forces raised the Imperial banner, and escaped to Edo.[26] He placed himself under voluntary confinement, and indicated his submission to the imperial court. However, a peace agreement was reached wherein Tayasu Kamenosuke, the young head of a branch of the Tokugawa family, was adopted and made Tokugawa family head;[27] On April 11, Edo Castle was handed over to the imperial army,[28][29] and the city spared from all-out war.

Together with Kamenosuke (who took the name Tokugawa Iesato), Yoshinobu moved to Shizuoka, the place to which Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of Tokugawa shogunate, had also retired, centuries earlier. Iesato was made the daimyō of the new Shizuoka Domain, but lost this title a few years later, when the domains were abolished.

Many of the hatamoto also relocated to Shizuoka; a large proportion of them did not find adequate means to support themselves. As a result, many of them resented Yoshinobu, some of them to the point of wanting him dead.[30] Yoshinobu was aware of this, and was so afraid of assassination that he redesigned his sleeping arrangement to confuse any potential assassin.[31]

Later life

Living a life in quiet retirement, Yoshinobu indulged in many hobbies, including oil painting, archery, hunting, photography, and cycling.[32] Some of Yoshinobu's photographs have been published in recent years by his great-grandson, Yoshitomo.[33]

In 1902, the Meiji Emperor allowed him to reestablish his own house as a Tokugawa branch (bekke) with the highest rank in the peerage, that of prince (kōshaku), for his loyal service to Japan.[34] He took a seat in the House of Peers, resigning in 1910. Tokugawa Yoshinobu died on November 21, 1913, at 4:10 pm and is buried in Yanaka Cemetery, Tokyo.

On 9 January 1896 his ninth daughter Tsuneko Tokugawa (1882–1939) married Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu, a second cousin to both Emperor Shōwa and Empress Kōjun and nephew of Prince Kan'in Kotohito.

On 26 December 1911 his granddaughter Kikuko Tokugawa was born. She married Prince Takamatsu, the brother of Emperor Shōwa, to become Princess Takamatsu.

Honors

With information from the corresponding article in the Japanese Wikipedia

- Prince (3 June 1902)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (30 April 1908)[35]

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (22 November 1913; posthumous)

Order of precedence

- Third rank (first day, 12th month of the fourth year of Koka (1847))

- Second rank (10th day, 12th month of the first year of Keio (1865))

- Senior second rank (fifth day, 12th month of the second year of Keio (1866); degraded 28th day, ninth month of the second year of Meiji (1869))

- Fourth rank (appointed 6 January 1872, following degradation in 1869)

- Senior second rank (18 May 1880, restored)

- Junior first rank (20 June 1888)

Eras of Yoshinobu's bakufu

The years in which Yoshinobu was shōgun are more specifically identified by more than one era name or nengō.

Family

- Father: Tokugawa Nariaki

- Mother: Arisugawa Yoshiko (1804–1893)

- Wife: Ichijo Mikako (1835–1894)

- Concubines:

- Isshiki Saga (1839–1929)

- Shinmura Nobu (1852–1905)

- Nakane Sachi (1836–1915)

- Children:

- Nagako (1878–1878) by Nobu

- Namiko (1880–1954) by Nobu married Matsudaira Hitoshi, son of Matsudaira Naritami

- Kuniko (1882–1942) by Nobu married Okouchi Kiko

- Itoko (1883–1953) by Nobu married Shijo Ryuai

- Danshi (1884–1884) by Nobu

- Yashi (1885–1886) by Nobu

- Yoshiko (1891–1891) by Nobu

- Kaneko (1875–1875) by Nobu

- Genji (1871–1872) by Nobu

- Takuma (1873–1873) by Nobu

- Kaito (1871–1872) by Saga

- Tokugawa Kyoko (1873–1893) married Tokugawa Satotaka (1856–1941) by Saga

- Tokugawa Tetsuko (1875–1921) married Tokugawa Satotoshi by Saga

- Hitoshi (1878–1878)

- Ryohime (1880–1880)

- Tokugawa Eiko (1887–1924) married Tokugawa Satotaka

- Tokugawa Yoshihisa (1884–1922) by Saga

- Tokugawa Atsushi (1874–1930) by Nobu

- Tokugawa Makoto (1887–1968) by Nobu

- Katsu Kuwashi (1888–1932) by Saga

- Ikeda Nakahiro (1877–1948) inherited Tottori Domain by Saga

- Hachisuka Fudeko (1876–1907) married Hachisuka Masaaki by Nobu

- Tokugawa Tsuneko (1882–1939) married Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu by Saga

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Tokugawa Yoshinobu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Patrilineal descent

| Patrilineal descent |

|---|

|

Yoshinobu's patriline is the line from which he is descended father to son. The existence of a verifiable link between the Nitta clan and the Tokugawa/Matsudaira clan remains somewhat in dispute.

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ Takano, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, p. 26. Sons of the lord of Mito did not bear the name Tokugawa unless they themselves became the next lord.

- ↑ Tokugawa, Tokugawa yonbyakunen no naishobanashi, pp. 138–140.

- ↑ Takano, p. 28.

- ↑ Takano, p. 38.

- ↑ Takano, p. 48.

- ↑ Borton, Japan's Modern Century, p. 40.

- ↑ Borton, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Takano, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Murray, Japan, p. 362; Kobiyama, Matsudaira Katamori no shōgai, p. 75; Bolitho, Collapse of the Tokugawa Bakufu, p. 9.

- ↑ Kobiyama, p. 75.

- ↑ Takano, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Kobiyama, pp. 84–87; Totman, p. 45; Takano, p. 20.

- ↑ See Japan 1853–1864, Or, Genji Yume Monogatari, trans. by Ernest Mason Satow. (Tokyo: Naigai Shuppan Kyokai), for more.

- ↑ Borton, p. 63.

- ↑ Tokugawa, Tokugawa yonbyakunen no naishobanashi, vol. 2, p. 162.

- ↑ Sims, French Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan, 1854–95, p. 236.

- ↑ Treat, Japan and the United States: 1853–1921, p. 89

- 1 2 3 Beasley, The History of Modern Japan, p. 96.

- ↑ Takano, p. 256.

- ↑ Yamakawa, Aizu Boshin Senshi, pp. 7–9.

- 1 2 Beasley, p. 97.

- ↑ Beasley, p. 97; Yamakawa, Aizu Boshin Senshi, p. 148–151.

- ↑ Totman, p. 416. For a copy of the original text of the message, see Yamakawa, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Totman, p. 417.

- ↑ Sasaki, pp. 23–24; Bolitho, pp. 420–422.

- ↑ Kobiyama, p. 124.

- ↑ Griffis, The Mikado: Institution and Person, p. 141.

- ↑ Takano, p. 267.

- ↑ Tokyo, an administrative perspective. Tokyo Metropolitan Government. 1958. p. 21. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Tokugawa Munefusa, Tokugawa yonbyakunen no naisho banashi, vol. 1, p. 131

- ↑ Tokugawa, pp. 131–133

- ↑ Tokugawa, pp. 136–138.

- ↑ For an example of Yoshinobu's photography, see: Tokugawa Yoshitomo, Tokugawa Yoshinobu-ke e yōkoso, p. 73.

- ↑ Takano, p. 273.

- ↑ Ibaraki Prefecture e-newsletter Archived 2007-12-02 at the Wayback Machine.

References

- Beasley, William G. (1963). The modern history of Japan. (New York: Praeger).

- Borton, Hugh (1955). Japan's Modern Century. (New York: The Ronald Press Company).

- Griffis, William Elliot. (1915). The Mikado: Institution and Person. (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- Kobiyama Rokurō (2003). Matsudaira Katamori no shōgai. (Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha).

- Murray, David (1905). Japan. (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons).

- Sasaki Suguru (1977). Boshin sensō. (Tokyo: Chūōkōron-shinsha).

- Sims, Richard L. (1998). French Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan, 1854–95. (London: Routledge).

- Takano Kiyoshi 高野澄 (1997). Tokugawa Yoshinobu: kindai Nihon no enshutsusha 德川慶喜 : 近代日本の演出者. (Tokyo: Nihon Hōsō Shuppan Kyōkai 日本放送出版協会).

- Tokugawa Munefusa 徳川宗英 (2004). Tokugawa Yonhyaku-nen no naisho-banashi 徳川四百年の内緒話 Vol. 1. (Tokyo: Bungei-shunju).

- Tokugawa Munefusa 徳川宗英 (2004). Tokugawa Yonhyaku-nen no naisho-banashi 徳川四百年の内緒話 Vol. 2: Raibaru tekishō hen. (Tokyo: Bungei-shunju).

- Tokugawa Yoshitomo 徳川慶朝 (2003). Tokugawa Yoshinobu-ke ni Yōkoso: Wagaya ni tsutawaru aisubeki "Saigo no Shogun" no Yokogao 徳川慶喜家にようこそ わが家に伝わる愛すべき「最後の将軍」の横顔. (Tokyo: Bungei-shunju). ISBN 4-16-765680-9

- Totman, Conrad (1980). The Collapse of the Tokugawa Bakufu, 1862–1868. (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press)

- Treat, Payson J. (1921). Japan and the United States: 1853–1921. (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company).

- Yamakawa Kenjirō (1933). Aizu Boshin Senshi. (Tokyo: Tokyo Daigaku Shuppankai).

Further reading

- Matsuura Rei 松浦玲 (1975). Tokugawa Yoshinobu: shōgun-ke no Meiji-ishin 德川慶喜 : 将軍家の明治維新. (Tokyo: Chūōkōronsha 中央公論社).

- Satow, Ernest Mason, trans. (1905). Japan 1853–1864, Or, Genji Yume Monogatari. (Tokyo: Naigai Shuppan Kyokai).

- Shibusawa Eiichi 渋沢栄一, ed. (1967–1968) Tokugawa Yoshinobu-kō den 德川慶喜公伝. (Tokyo: Heibonsha 平凡社).

Works of fiction

- Shiba, Ryōtarō (1998). The Last Shogun: The Life of Tokugawa Yoshinobu, trans. Juliet Winters Carpenter. (New York: Kodansha International). ISBN 1-56836-246-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tokugawa Yoshinobu. |

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Tokugawa Iemochi |

Shōgun: Tokugawa Yoshinobu August 29, 1866 – November 19, 1867 |

Shogunate abolished |