This is a timeline of music in the United States from 1880 to 1919.

1880

- George Upton's "Women in Music" is the "first of many articles and reviews by prominent male critics which sought to trivialize and undermine the achievements of what was considered an alarming number of new women composers in the realm of 'serious' classical music".[1]

- The Native American Sun Dance is banned.[2]

- John Knowles Paine's second symphony, In Spring, premiers in Boston, and is "received with unparalleled success".[3]

- Gussie Lord Davis has his first hit with "We Sat Beneath the Maple on the Hill", making him the first African American songwriter to succeed in Tin Pan Alley.[4]

- Patrick Gilmore's Twenty-Second Regimental Band becomes the first fully professional ensemble of any kind in the country to be engaged in performances full-time, year-round.[5]

1881

- Henry Lee Higginson forms the Boston Symphony Orchestra; Higginson would personally run the Orchestra for almost four decades.[6][7]

- The Thomas B. Harms music publishing company is established solely to publish popular music, then referring to parlor music.[8]

- Tony Pastor becomes an established theater owner on 14th Street in New York City, where he becomes the first person "to bid... for women customers in the variety theater", bringing that field out of "disreputable saloons" and transforming it "into decent entertainment that respectable women could enjoy".[9][10]

1882

| Mid-1880s music trends |

- The Office of Indian Affairs outlaws a wide range of Native American customs and rituals, having begun with the Sun Dance in 1880.[2]

- Norwegian American choirs begin to form organizations, putting together festivals and other periodic gatherings to celebrate Norwegian culture and music.[21]

|

1883

- The Metropolitan Opera opens in New York City.[7][22][23]

- C. C. Perkins and J. S. Dwight publish the first history of a musical society in the United States, that of the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston.[24][25]

- John Slocum, who began preaching revelations the year before, is seen as being healed by his wife Mary's prayers; the Slocums' followers come to create the Shaker Church, of which music is an integral part.[26]

- F. L. Ritter publishes the first comprehensive music history of the United States, Music in America.[27]

- The Freeman, an Indianapolis, Indiana-based periodical, is founded, soon becoming the primary trade paper for African American theatrical groups.[28]

- Gretsch becomes the first drum manufacturer in the United States.[29]

- J. S. Putnam's "New Coon in Town" is one of the first hit coon songs to be published.[30]

1885

- Charles Fletcher Lummis begins one of the earliest collections of Spanish folk songs soon after he arrives in Los Angeles.[36]

- M. Wittmark and Sons is formed to focus exclusively on publishing popular parlor music.[8]

- A Hawaiian schoolboy named Joseph Kekuku is credited with inventing the Hawaiian guitar, in which strings are melodically picked and stopped by a metal bar, with the guitar held across the lap.[37][38]

- Scott Joplin arrives in St. Louis, Missouri and soon becomes a fixture at the Silver Dollar Saloon, beginning his career which will put "his creative stamp on that great body of music that came to be known as classic ragtime".[39][40] The Saloon is owned by John Turpin, an important patron of ragtime whose son, Thomas Million Turpin is known as the "Father of St. Louis Ragtime".[41]

- The Chicago Music Company releases the first opera by an American woman to be published, The Joust, Or, The Tournament, by G. Estabrook[42]

- The Anglo-Canadian Music Publishers' Association is formed to protect the copyrights of European music publishers.[43]

1886

- (Approximate) Wovoka, a medicine man of the Northern Paiute, articulates the messianic message of the Ghost Dance spiritual movement, which fused Christian (particularly Presbyterian and Mormon) teachings with those of Wovoka's father, Ta'vibo, which revolved around traditionalism and resurrection.[44]

- Several Swedish American choirs join together to form the Union of Scandinavian Singers, which becomes a major part of the Swedish American music industry.[21]

- John Philip Sousa's "The Gladiator March" sells more than a million copies, marking a turning point in his career.[45]

- The principal international agreement on copyright, the Berne Convention, is signed; the United States will not sign until 1989.[46]

1889

- Antoni Mallek forms the Polish Singers Alliance, an influential national Polish American organization.[54]

- The composer Edward McDowell premiers his Piano Concerto No. 2 in New York, establishing him as one of the most prominent composers of the era.[55]

- W. S. B. Matthews' A Hundred Years of Music in America is the first attempt at a history of "popular and the higher music education" in the country; it hails Lowell Mason as the founder of American music.[24][56]

- The first African American woman to compose a produced opera is Louisa Melvin Delos Mars, with Leoni, the Gypsy Queen.[57] She is also one of the three women who each became the first to have an operetta they composed produced, along with Emma Marcy Raymond's Dovetta and Emma Roberts Steiner's Fleurette.[42]

- John Philip Sousa's "The Washington Post" establishes his reputation as the country's foremost composer of marches.[58]

- Ethnologist J. Walter Fewkes becomes the first to use a phonograph, a treadle-run machine, to record Native American music and speech[59]

- Harriett Gibbs Marshall becomes the first African American woman to graduate with a degree in music from Oberlin College. She will go on to found the Washington Conservatory of Music.[60]

- Louis Glass installs a coin-operated phonograph in a saloon in San Francisco,[61] the first predecessor of the jukebox.[62]

- Columbia Records releases the first catalog of recordings, consisting of ten pages worth of cylinder recordings. The catalog is intended primarily for jukeboxes.[63]

1890

- An era that has been called a "golden age" begins, centered around a group of composers in Boston including John Knowles Paine, Horatio Parker, George Whitefield Chadwick, Arthur Foote and Amy Beach. This group is variously called the Second New England School, the Boston Classicists or the Boston Academics[64]

- Native American music is recorded for the first time.[65]

- The Tin Pan Alley neighborhood begins to form in New York City, and Oliver Ditson & Co. becomes the most prominent music publisher of the era.[66]

- A Trip to Chinatown is a historical theatrical production, running for a record 657 performances.[8]

- Jesse Walter Fewkes makes the first musical field recordings, specifically of Passamaquoddy songs and stories, performed in Calais, Maine by Peter Selmore and Noel Josephs.[16][67]

- The Ghost Dance, a Native American spiritual movement, of which music and dance were integral parts, is banned after the Wounded Knee Massacre.[44]

- Sam Jacks' Creole Burlesque Company opens in New York, and is a popular novelty act, unusual for a time in that the cast includes both men and women, and the show's format is more variety than minstrel show.[68]

- Samuel W. Cole leads what is probably the first high school production of a full oratorio in the country.[69]

1891

- The Chicago Symphony Orchestra forms, with income from backers who pledged $1000 for each of three years. The backers formed an Orchestral Association, which hired a music director. Many cities subsequently used the same model, including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Cincinnati and Minneapolis.[6][7]

- Leopold Vincent publishes the Alliance and Labor Songster, a pioneering early collection of labor songs.[70]

- Carnegie Hall is built in New York City as a venue for classical performances.[71] It will become the foremost concert stage in the city.[72]

- Changes in copyright law under the International Copyright Act of 1891 make it impossible to publish foreign music without payment to the original composer or publisher.[73] This stimulates the establishment of American subsidiaries of foreign publishing companies.[74]

- A Trip to Chinatown is first published; it can be considered one of the first examples of American musical theater, as it consists of a single plot that the entire production revolves around.[7]

- Charles Davis Tillman (1861–1943) publishes "The Old Time Religion" to his largely white audience.[75]

1892

- Bohemian composer Antonín Dvořák arrives for a stay in the United States as director of the National Conservatory in New York.[76] He becomes a fierce advocate for cultural and musical nationalism, and is very interested in American music incorporating African American and Native American music.[7][11]

- Papa Jack Laine, a white drummer and saxophonist from New Orleans, claims that he is the first to use the first saxophone in the proto-jazz bands of New Orleans. He is sometimes said to have formed the first ragtime band as well.[77] Laine is considered one of the first white jazz musicians.[78]

- John Philip Sousa forms a band that set a new standard for American professional bands, having left the U.S. Marine Band.[79] He and his band will be the most prominent and influential professional symphonic group at the peak of popularity for bands of that sort.[7]

- Charles K. Harris premiers "After the Ball", a waltz typical of the time,[8] which is said to be the most popular song of the decade,[80] and the biggest hit of the century.[81] It is interpolated into a play, and the sheet music is said to have sold more than five million copies.[8]

- Harry Lawrence Freeman becomes the first African American to have an opera he wrote produced, his first work, Epthelia. He will become known for combining secular and sacred African American music with traditional Western opera.[82]

| Early 1890s music trends |

- Irish-American dominance in musical theater ends.[83]

- The husband-and-wife duo Dora Dean and Charles E. Johnson, in Sam T. Jack's Creole Show, become probably the first African Americans to perform the cakewalk onstage.[84]

|

1893

- Alice Fletcher begins her prolific scholarly career with a study of the music of the Omaha tribe of Native Americans.[85][86] The study, done with the assistance of Francis La Flesche, took ten years to complete.[24]

- The World's Columbian Exposition, a watershed in American culture,[87] attracts attention to the Chicago ragtime scene, led by patriarch Plunk Henry and exemplified in performance at the Exposition by Johnny Seymour[88] and Scott Joplin[89] Violinist Joseph Douglass achieves wide recognition after his performance there, and will become the first African American violinist to conduct a transcontinental tour, and the first to tour as a concert violinist.[90][91] The first Indonesian music performance in the United States is believed to occur at the Exposition.[92] At the same event, an ensemble of musicians with a dancer known as Little Egypt, is the first exposure to Middle Eastern culture for many Americans,[93] while a group of hula dancers leads to an increased awareness of Hawaiian music among Americans throughout the country.[37]

- Katherine Lee Bates writes "America the Beautiful" at Pike's Peak, Colorado. Though "The Star-Spangled Banner" will be chosen, "America the Beautiful" will be the other major option for a national anthem when it is chosen in 1931.[94]

- Czech composer Antonín Dvořák calls spirituals "all that is needed for a great and noble school of music".[95]

- Jane Addams' Hull House in Chicago is the first music school connected to the settlement work.[96]

- Philosopher Richard Wallaschek sparks the "origins" controversy when he puts forth the claim that African American spirituals are primarily derived from European music.[97] This will not be solved conclusively until the 1960s, when scholars showed that spirituals were "grounded in African-derived music values yet shaped into its distinctiveness as a direct result of the North American sociocultural experience".[98]

- The first Chinese opera theater in New York City is opened in Chinatown.[19]

- The murder of Ellen Smith in Mount Airy, North Carolina leads to the composition of "Poor Ellen Smith", set to the melody of "How Firm a Foundation"; the subsequent controversy regarding the trial of Peter DeGraff for her murder leads to the song's spread across the state, so much so that Forsyth County, North Carolina banned the singing of "Poor Ellen Smith".[99]

- Ruthven Lang's Dramatic Overture is presented by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, marking the first time that institution had performed the work of an American woman composer.[100]

| Mid 1890s music trends |

- The massacres of numerous Armenians in Turkey leads to the first wave of large-scale Armenian immigration to the United States, and the beginning of Armenian American music.[93]

- The public exhibition of motion pictures, almost always with live music played locally, begins.[101]

- The bands of John Robichaux and Buddy Bolden in New Orleans become the top dance bands of the era, and frequently competitive, both economically and in actual performances. These bands are a significant precursor of jazz.[102]

|

1894

- The Standard Quartette of Chicago becomes the first commercial recording of an African American singing quartet.[103]

- The Black Extravaganza, an outdoor concert in New York City, featuring the Four Harmony Kings, the Old South Quartette and other popular African American musicians, a "breakthrough" show in the history of African American music.[104]

- Henry Franklin Belknap Gilbert begins presenting concerts of Slavic music Harvard University, one of the first American composers to incorporate Slavic elements.[105]

- Orville Gibson begins selling guitars, his technical innovations helping to spread the instrument throughout the United States.[106]

- New Orleans, Louisiana passes a law requiring Creoles to live uptown, thus bringing them and their music into closer contact with African Americans.[102]

- Approximate: Dee Dee Chandler is the first "dance drummer to use the foot pedal.[107]

- Edward B. Marks and Joe Stern hire George Thomas to "illustrate" through Magic lantern glass slides the lyrics of their song "The Little Lost Child" being performed by a group of Primrose and West minstrels. This was probably the first-ever example of a "music video".[108][109]

- E. B. Marks forms a music publishing company, which will become one of the first to publish African American songwriters with great success.[110]

1895

- The Octoroon becomes the first "important black (theatrical) production".[8]

- Charles L. Edwards publishes Bahama Songs and Stories, featuring spirituals collected in the Bahamas, much of the population of which, at the time, was descended from African American slaves.[111]

- Alice Fletcher makes the first known recordings of the Ghost Dance, specifically the songs of two Southern Arapaho men who were visiting Washington, D.C., Left Hand and Row of Lodges.[26] Some of her previous research had inspired Frances Densmore, who began series of very successful lectures on Native American music.[112]

- The first permanent orchestras are established in Cincinnati and Pittsburgh.[7]

- John Philips Sousa's El Capitan is his most successful operetta, and will run continuously from 1896 to 1900 in North America.[113]

- The murder of William Lyons by Lee Shelton in St. Louis will inspire a ballad called "Stagger Lee", which will be recording more than 150 times since 1897, making Lee the most prominent criminal in American folk music.[114]

- With The Wizard of the Nile, Victor Herbert launches a string of forty successful operettas, several of which have become staples of the American repertoire and produced a "lasting heritage of popular songs".[115]

- The American Federation of Musicians is founded.[116]

- Thaddeus Cahill's Telharmonium (Dynamophone) is one of the earliest, and possibly still the largest, electric instrument.[117]

- Aeolian introduces the Aeriola player piano.[61]

1896

- The American Federation of Musicians is founded.[118]

- Edward McDowell's Indian Suite is premiered; it is an influential work that incorporates aspects of Native American music.[119] He is also offered the first music professorship at Columbia University, whose nominating committee praises him as "the greatest musical genius America has produced".[120]

- Six booking agents pool their resources to form the Syndicate, which came to control theaters in New York and across the country.[121]

- The first "distinctively syncopated songs (are) published under the 'ragtime' label".[122] These include "My Coal Black Lady" by W. H. Krell and Ernest Hogan's "All Coons Look Alike to Me".[123]

- The Church of God and Saints of Christ is founded in Oklahoma by William Saunders Crowdy. The Church is known in part for a "self-sufficient musical tradition without equal that consumes more than half of any service".[124]

- James Mooney publishes a monograph of Native American Ghost Dance songs, which are first commercially released this year by the National Gramophone Company; it is probable that the recordings are of Mooney or his brother Charles.[26]

- Ernest Hogan's "All Coons Look Alike to Me" is an immediate hit,[125] and launches a fad for syncopated coon songs that lasts until World War I.[126] The published version carries a caption, describing the second chorus, which is the "earliest association of the word rag (as in ragtime) to instrumental music".[127]

- Gussie L. Davis, the most successful African American songwriter in Tin Pan Alley, has his biggest hit with "In the Baggage Coach Ahead".[128]

- Amy Cheney Beach's Gaelic Symphony is the first symphony composed by a woman to be performed, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[100] Beach will be accepted as the first American female "composer of significance" in the country.[129]

- Homer A. Norris publishes Practical Harmony on a French Basis, a precursor and harbinger of American classical music's upcoming move from a German-oriented style to a French one.[130]

- Tom Turpin's "Harlem Rag" is the first published ragtime song.[131]

- Vaudeville shows begin using motion pictures.[132]

- John Phillips Sousa's El Capitan becomes the first major American operetta.[133]

| Late 1890s music trends |

- The first music festival celebrating Finnish American culture are organized by various Finnish temperance societies.[21]

|

1897

- The "golden age" of composition in the Second New England School ends.[64]

- The Library of Congress creates a section for music-related materials.[134]

- Bob Cole and Billy Johnson compose A Trip to Coontown, one of the productions that helped to establish the field of African American musical comedy.[57] It is the first black show to appear on Broadway.[135]

- Buddy Bolden's band begins performing; some will consider this the first jazz band,[126] and Bolden the first jazz musician.[136] Bolden is an influential cornetist in the early history of jazz,[137] and his band innovates the use of the string bass in place of the tuba.[138]

- Paul Dresser writes "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away", one of his most popular songs and later the state song of Indiana.[139]

- William H. Krell copyrights "Mississippi Rag", the first "published piano piece to include the word rag (as in ragtime) in its title". It is advertised as the first ragtime song.[140] However, Theodore Northrup's "Louisiana Rag", published later in the year, is sometimes considered the first "genuine piano rag".[133][141] Tom Turpin's "Harlem Rag", the first rag composed by an African American to be published, is also published in this year, and the first ragtime recordings are made by Vess L. Ossman and the Metropolitan Band, while Ben Harney, pianist-composer, publishes the Rag-time Instructor.[142] The first actual use of the word in a popular media ragtime is in a Chicago newspaper article this year.[143][144]

- New Orleans, led by Alderman Story, sets up a prostitution district called Storyville. Musicians gravitate there, and the area becomes a hotbed of innovation and a major part of the origins of jazz.[102][145]

- Henry Sloan, a legendary, little-known bluesman, played the blues as early as this year. He will go on to mentor Charley Patton, one of the earliest bluesmen.[146]

1898

- Ragtime songs begin to appear on the stage.[147]

- Will Marion Cook's Clorindy, or The Origin of the Cake Walk and Bob Cole's A Trip to Coontown are the first musicals "written, directed and performed by African American artists".[8] Clorindy, a ragtime operetta, introduced "syncopated 'hot' music to Broadway" and starred Ernest Hogan.[82] A Trip to Coontown is the "first full-length musical play written and produced by blacks on Broadway",[148][149] and the first black operetta in the modern syncopated style.[150] It is a harbinger of a new style: the American musical theater.[135]

- Music education is first introduced into the public school system of New York City.[151]

- Victor Herbert's "Romany Life" is the first major American composition in the Hungarian "Gypsy" style.[7]

- Puerto Rico becomes a part of the United States, leading to the arrival of numerous immigrants and with them, Puerto Rican music in New York City and elsewhere.[152]

- The first African Methodist Episcopal hymnal to contain written music is published.[153]

- The first African American nationalist composer, Harry T. Burleigh, "to achieve national distinction as a composer, arranger, and concert artist" begins composing.[154]

- The National Federation of Music Clubs, the largest music teachers association in the country, is founded.[151]

- The William Morris Agency is founded. It will be the largest agency in the country by the end of the 20th century.[155]

- Wurlitzer builds the first coin-operated player piano.[61]

1899

- Scott Joplin's "Maple Leaf Rag" is published by John Stillwell Stark in Sedalia, Missouri; the song is a "landmark in American music history" and is a great commercial success, unprecedented for a black composer.[156][157] It remains the most famous and popular piano rag,[126] and "establishe(s) a model for classic ragtime that (will be) emulated by all rag composers interested in serious composition". Since its first publication, Maple Leaf Rag has never been out of print.[158][159]

- The wildly popular "My Wild Irish Rose" continues the popular Irish song tradition within the United States.[7]

- Eubie Blake's "Charleston Rag" is published; it is his "first and most famous ragtime piece", and it will establish his career as one of the top composers of Eastern ragtime.[160]

- African-English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor attends a concert held by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, inspiring him to create a collection of African-derived melodies, arranged for the piano. The Bamboula becomes the most popular, and his works make a "marked impression on the American public, particularly in black communities".[161]

- Perry J. Lowery becomes the "first black musician to take his vaudeville acts into the circus", with his group's performance in Madison Square Garden for the Sells and Forepaugh Brothers Circus.[162]

- The Jewish chorister's union strikes for wages rather than profit shares.[163]

1900

- Violinist and cornetist Helen May Butler's Ladies Military Band begins touring, bucking "stereotypes of the time by showing that women could endure the rigors of touring life and lease enough paying customers to survive in the music business".[165]

- The vaudeville musical theater format begins to take shape.[166]

- Symphony Hall is built in Boston.[71]

- The first permanent orchestra is established in Philadelphia.[7]

- J. Rosamond Johnson and James Weldon Johnson compose "Lift Every Voice and Sing", the official anthem of the NAACP.[82]

- Harry Von Tilzer's "A Bird in a Gilded Cage" is released, becoming his "most famous and enduring" composition.[167]

- Amy Cheney Beach becomes the first American woman composer to perform as a soloist on her own work, the Piano Concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[100]

- Pat Chappelle organizes an African American theater touring company, initially based in Jacksonville, Florida but from 1918 in Port Gibson, Mississippi, to produce musicals, beginning with A Rabbit's Foot. It becomes phenomenally successful, and would go on to employ many of the early African American blues and vaudeville performers, including Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey.[168]

- Fred Stone's "My Ragtime Baby" wins a prize at the Paris Exposition, performed by John Philips Sousa's band. This is the first exposure of ragtime to most Europeans.[169]

- The Bach Choir of Bethlehem begins a series of annual concert festivals presenting the music of Johann Sebastian Bach; these festivals are a "major early stimulus" in the revival of Bach's compositions.[170]

- The first two music education periodicals begin to be issed: School Music and School Music Monthly.[171]

- Steel strings for the guitar are introduced, making the instrument more easily heard in crowded and noisy settings, which helps the guitar spread across the South.[106]

- Florodora, with music and lyrics mostly by Leslie Stuart, becomes the first piece of musical theatre to be recorded by its original cast.[172]

1903

- Will Marion Cook's Walker and Williams in Dahomey, with the comic duo George Walker and Bert Williams, is the first black show on Broadway,[187][188] and the "first with an all-black cast".[8][189] Walker and Williams would go on to star in many major productions, and would "revolutionize black theater".[190] Williams will become the first and most important African American performer in vaudeville and on Broadway.[191]

- Enrico Caruso becomes a major star after performing at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.[192] He will be the first internationally renowned performer to realize the full potential of audio recording technology.[193]

- The first permanent orchestra is established in Minneapolis.[7]

- The publication of Francis O'Neill's O'Neill's Music is a milestone in Irish American music history.[194]

- J. Berni Barbour and N. Clark Smith found the "first relatively permanent (African American) music publishing" company, in Chicago; it is also "probably the first black-owned music publishing company in history".[195]

- Wilbur Sweatman and his band record "Maple Leaf Rag" in Minneapolis, Minnesota, becoming the first African American group to record.[196]

- Early music performer and instrument maker Arnold Dolmetsch moves to the United States. His work with the Chickering company is a landmark of American early music performed on period instruments.[170]

- The first recordings of African American music - camp meeting shouts - are made by the Victor Talking Machine Company.[131]

- The first popular recorded song dealing with the subject of death is Theodore F. Morse's and Edward Madden's "Two Little Boys".[197]

- W. C. Handy is in Tutwiler, Mississippi, and hears a blues performance. This inspires his career, and is said to be the first documentation of actual blues and the use of the slide guitar.[198]

1905

- Victor Herbert, a popular songwriter, publishes the operetta Mlle. Modiste, which is successful and launches the hit song "Kiss Me Again".[8]

- Most blues performers born before this year generally considered themselves musicians whose repertoire included a wide variety of musical styles; those born later will mostly view themselves as playing a distinct genre.[203]

- The first large-scale Filipino immigration to the United States begins, thus beginning the Filipino American musical tradition.[204]

- Hawaiian music is commercially recorded by Columbia and Victor Records, achieving surprising success throughout the country.[37]

- Arthur Farwell publishes Folk-Songs of the West and South, a collection of songs that include "The Lone Prairee", which Farwell called the first cowboy song to be printed, both words and music".[205]

- Robert Motts founds the first permanent black theater, in Chicago, the Pekin Theatre.[206]

- The Philadelphia Concert Orchestra becomes the first black symphony in the North.[185]

- Ernest Hogan creates a vaudeville act that is the "first syncopated music concert in history".[207] The performers are the Memphis Students, organized by James Reese Europe and later led by Will Marion Cook. The show featured a '"dancing conductor", Will Dixon, who danced rhythms to keep the band performing tightly, and the band's drummer, Buddy Gilmore, used unusual noisemaking devices besides drummers. Unorthodox folk instruments are also used in place of the traditional brass and woodwind lineup. The group was the first to "introduce the concept of the 'singing band' to the entertainment world", and performed in a style now known as barbershop music for some songs.[208]

- Hallie Anderson begins promoting a well-attended Annual Reception and Ball. She is the first major American woman conductor.[209]

- Harvard University grants the first PhD in music in the country.[151]

- A standardized piano roll, capable of being fitted to any model of instrument, is introduced.[29]

1906

- At a Congressional hearing, John Philips Sousa testifies that the phonograph was discouraging Americans from performing themselves.[210]

- The United Booking Office of America forms to connect theater managers and performers in the eastern United States.[166]

- The Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, led by William J. Seymour, an integral part of the origin of Holiness-Pentecostal-style gospel music.[177]

- Freddie Keppard becomes bandleader of the Olympia Band, soon becoming one of the most prominent jazz trumpeters in that city. He will later turn down a recording contract, fearing it will make his music too easy to steal; the contract will instead be given to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, who will become national stars.[211]

- The first African American orchestra in the nation to be incorporated is in Philadelphia.[212]

- The first radio broadcast of music is sent by Reginald A. Fessenden in Brant Rock, Massachusetts.[213]

- The Victor Talking Machine Company releases the Victrola, the most popular gramophone model until the late 1920s.[214] The Victrola is also the first playback machine containing an internal horn.[193] Victor also erects the world's largest illuminated billboard at the time, on Broadway in New York, to advertise the company's records.[215]

- The Gabel Automatic Entertainer is an early jukebox-like machine, the first to play a series of gramophone records.[216]

1907

- Richard Strauss' Salome premiers in New York at the Metropolitan Opera, to great controversy over the scandalous subject matter.[22]

- Beginning with Franz Lehár's The Merry Widow, light operettas, or comic operas, begin to dominate the theaters of Broadway.[217]

- The Intercolonial Hall on Dudley Street in Boston opens as a social club for Irish Americans and Canadians. It will be one of the preeminent Irish music venues in the country during the mid-20th century.[218]

- Scott Joplin publishes "Gladiolus Rag" with Joseph W. Stern, intending to "reposition ragtime in the sheet music marketplace by playing down its African American roots."[219]

- The battle over cultural ownership of the patriotic song "Dixie" continues, with Southerner William Shakespeare Hays claiming to have written the song in 1858. He is able to convince the Filson Club of Louisville, Kentucky.[220]

- The migration of Japanese-Hawaiians to the mainland United States is banned, preceding a ban on labor emigration in Japan, effectively isolating Japanese Americans on the mainland and in Hawaii, both from each other and from Japan itself.[34]

- Florenz Ziegfeld launches the show that will become known as Ziegfeld's Follies, which "enlarged the scope of entertainment with every kind of extravagant presentation, including current topics, comedy routines, and of course, the ever-present gorgeous girls.[221] It will "set the standard and (break) box-office records".[222]

- Natalie Curtis Burlin publishes The Indians Book, a "definitive collection" of songs that "set the standard for all future musicologists in the study" of Native American music.[223]

- The Music Educators National Conference is founded.[151]

- A Victor Records recording of Enrico Caruso singing "Vesti la Giubba" becomes the first to sell a million copies.[48]

- The Green Mill opens in Chicago. As of 2009, it is the oldest extant nightclub in the city.[224]

1908

- Arturo Toscanini becomes the conductor of the Metropolitan Opera; he is lauded for "his energy, the command he brought to the podium, his demands for perfection, and his uncanny musical memory."[225]

- Scott Joplin publishes the education School of Ragtime, "a landmark in the development and diffusion of classic ragtime".[157]

- The first black bandmasters are appointed to the U.S. Army, for the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry and the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry regiments.[185]

- Edward L. Gruber composes "The Caissons Go Rolling Along", which, as "The Army Goes Rolling Along", will become the official song of the U.S. Army.[226]

- Frederick Converse's Iolan, Or, the Pipe of Desire is the first American full opera scores to be published abroad.[42]

- Antonio Maggio's "I Got the Blues" is the first published song to use the word blues.[131]

- N. Howard "Jack" Thorp's Songs of the Cowboys is the first published collection of cowboy music.[227]

- Sound recordings, along with photography and cinematography, are added to the Berne Convention, an international copyright agreement which the United States is not yet a signatory to.[46]

1909

- The Copyright Act is passed to secure royalties for composers on the sale of recordings and public performances.[228][229] It also required publishers of music to allow mechanical reproduction by anybody if they allow any individual to do so; furthermore, the law is the first in American history to intervene directly into the marketplace by setting a price for the use of private property, requiring payment of two cents to the copyright holder from the creator of each piano roll, recording cylinder and phonograph record.[230][231]

- Charles Wakefield Cadman's "From the Land of the Sky-Blue Water", a classical work using American indigenous musical themes, crosses over and becomes a surprise mainstream success.[7]

- The first African American bandmasters in the American military are appointed; these are Wade Hammond (Ninth Cavalry), Alfred Jack Thomas (Tenth Cavalry), William Polk (Twenty-fourth Infantry) and Egbert Thompson (Twenty-fifth Infantry).[232]

- Kurt Schindler organizes the MacDowell Chorus, soon known as the New York Schola Cantorum, one of the earliest ensembles in the country to gain recognition for performing Renaissance music.[170]

- John Phillips Sousa's operetta, The American Maid, is the first known American stage production to use motion pictures.[42]

- Charles "Doc" Herrold and his wife, Sybil, start the first college radio station.[213]

- The Theater Owners' Booking Agency is founded by the Barasso Brothers, S. H. Dudley and other black theater owner-managers. It will become the primary booking agency for African American performers of the era.[233]

- The first use of the word jazz in print, in reference to dancing.[234]

1910

- The Clef Club, the first booking agency for African American performers, is formed by James Reese Europe and others.[235][236] Europe would go on to make it into a performing orchestra as well.[185][237]

- Arthur Finlay Nevin's Poia is the first American opera accepted by one of the great European opera houses, the Royal Opera House of Berlin.[238] Later this year, Frederick Converse's Iolan, Or, the Pipe of Desire becomes the first American opera to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera.[42]

- Inayat Khan, a vina player, comes to the United States to spread Sufism, of the Chishti order.[239]

- Homer Allen Rodeheaver is hired by Billy Sunday, an influential development in the early history of gospel music. Rodeheaver will be the first gospel artist to record, and will found the first gospel label, Rainbow Records.[240] Music historian Don Cusic has called Rodeheaver the first American chorister perceived as a ladies' man or sex symbol.[241]

- John Lomax publishes a collection of cowboy songs, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, a ground-breaking publication that launched his career;[242] he is shortly afterwards elected president of the American Folklore Society.[243] This collection is the first of American folk songs to be printed with the music.[134]

- The Metropolitan Opera performs its first show by an American composer, with Frederick Converse's The Pipe of Desire.[244]

- The Mexican Revolution spurs a wave of immigration, mostly to states with large Mexican populations, like Colorado and New Mexico; these immigrants bring with them contemporary Mexican culture and helped to revitalize the indigenous music of the Hispanic Southwest.[245]

- The Music Supervisors National Conference is formed to promote music in public schools.[32]

- The New York Philharmonic Society ceases to be a musician-run cooperative, and is taken over by a board of directors.[6]

- The first convention of the Norwegian Singers Association of America is held.[21]

- Vassily Andreyev brings his balalaika and domra orchestra to the United States, inspiring a similar orchestra, supported by the Russian Orthodox Church, to form in St. Louis, followed by Chicago and New York in the next two years.[246][247]

- R. Nathaniel Dett becomes the "first black pianist to make a transcontinental tour of the nation".[201]

- Homer Rodeheaver publishes the first of many gospel song collections that will quickly become a major part of the repertoire for African American churches across the nation.[248]

- The Vaughan Quartet becomes first all-white and all-male professional gospel vocal quartet in the country.[249]

- "A Perfect Day" by Carrie Jacobs-Bond (1862–1946) sells 25 million copies. Bond becomes America's first woman to make a living as a composer.[250]

1911

- Alice Fletcher and Francis La Flesche publish The Omaha Tribe, a monograph that documents the music and culture of the Omaha; it is often called the first ethnomusicological work.[252]

- Irving Berlin's "That Mysterious Rag" is the first ragtime song to not revolve around explicitly black lyrical themes. Berlin shifts to describing his work in this style as "syncopated", rather than "ragtime".[253] His "Alexander's Ragtime Band" is "conspicuously representative" of the Tin Pan Alley songwriters,[254] and brings about a "brief revival of interest in (ragtime)" despite being the "swan song" of the ragtime era.[255]

- Charles Griffes moves away from a German Romantic style and towards a more free-form style that comes to include French, East Asian and other influences.[256]

- The first permanent orchestra is established in San Francisco.[7][257]

- The term barbershop quartet comes into usage with the release of "Mr. Jefferson, Lord, Play That Barbershop Chord".[258]

- The Victor Gramophone Company hires Frances Elliott Clark to create educational materials that could be sold alongside recordings, for the purpose of music education.[32][151]

- Henry Cowell's Adventures in Harmony is premiered in San Francisco, an early use of tone clusters in the field of classical music.[259]

- Mary Carr Moore composes Narcissa, or The Cost of Empire, with a libretto by her mother, Sarah Pratt Carr, which is "very likely the first grand opera to be composed, scored, and then conducted by an American woman".[260]

- A private performance of Treemonisha by Scott Joplin is the first of an African American "folk opera written by a black composer".[185]

- Raymond Lawson becomes the first known African American pianist to perform concertos with a symphony orchestra, the Hartford Symphony.[201]

- Victor Herbert's Natoma is the first American opera to display verismo (realism).[42]

- The United States Army's bandmaster school is founded at Fort Jay on Governors Island in New York,[261] led by Walter Damrosch and directed by Arthur A. Clappe.[262]

1912

- W. C. Handy publishes "The Memphis Blues",[263] a song he had written for the mayoral campaign of Edward Hull Crump;[264][265] its publication creates "an unprecedented vogue" for blues-styled songs, and made Handy's band the most popular in Memphis.[266] Earlier in the year, the first blues texts to be published were Artie Matthews's "Baby Seal Blues" and Hart A. Wand's "Dallas Blues".[267][268][269]

- Community dance halls begin to grow more common, as a number of new dances become a part of the American music scene.[270]

- The All-Kansas Music Competition Festival becomes the first contest devoted to music in schools.[262]

- Leopold Stokowski becomes the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, becoming well known for his showmanship.[271]

- James Reese Europe, the first black bandleader in the country,[72] presents the first Concert of Negro Music at Carnegie Hall, the first "organized attempt" to showcase African American music for mainstream audiences in New York.[24][272]

- Lydia Parrish begins going to St. Simons Island in the Sea Islands of Georgia, eventually founding the Spiritual Singers Society of Coastal Georgia.[273]

- Within a week of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, songs have been composed about the disaster, one being a ballad being sold by a black, seemingly blind, preacher to A. E. Perkins.[274]

- Cyrus H. K. Curtis gives the first public recital of organ music in the United States, in Portland, Maine.[275]

- George Whitefield Chadwick's opera The Padrone is rejected by the Metropolitan Opera on the basis that it was "probably too real to life" in its portrayal of "life among the humble Italians". The opera takes place in "the seamy side of Boston (which) Chadwick was the first to dramatize... musically and realistically".[276] It is among the earliest American operas to present its subject realistically.[42]

- John Stillwell Stark publishes Standard High-Class Rags, a collection of ragtime songs arranged for small orchestra. It will eventually become known as The Red-Backed Book of Rags, "and as such it (will be) a wellspring of the 1970s ragtime revival".[277]

- Helen Hagan becomes the first African American pianist to matriculate from Yale University with a Bachelor of Music, and is also the first to win the Sanford Fellowship.[201]

- David I. Martin and Helen Elise Smith found the Martin-Smith School of Music, "one of the most important black musical institutions" of the era.[278]

- A series of concerts begin to be held in New York, sponsored by the Clef Club and the Music School Settlement for Colored; these attract large, mixed-race audiences, and inspire other similar concerts in cities around the country. The most remarkable feature is the use of mandolin, banjo and other elements of African American folk culture by the Clef Club Symphony Orchestra.[279]

- The first piano-roll recordings of African American performers are made by the QRS company, a subsidiary of the Melville Clark Piano Company.[196]

1913

- The word jazz is used in print for the first time, in San Francisco in reference to "speed and excitement" in a game of baseball.[280] The word's first use to describe a genre of music this year as well, in the catalogue for the International Exhibition of Modern Art (Armory Show) in New York,[281] and in reference to US Army musicians "trained in ragtime and 'jazz'".[234]

- The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) is formed to take advantage of recent changes in copyright law on behalf of composers of music, specifically by collecting royalties from public performances of music.[73]

- Frances Densmore's research constitutes the most extensive description of traditional Ojibwe music,[282] and the "largest collection ever published from one tribe".[112]

- Ragtime is a major part of a brief craze for social and ballroom dancing, which spurs the rise of two well-known dancers, Vernon and Irene Castle, especially after their performance in Watch Your Step the following year.[283] They work with James Reese Europe, whose band becomes the first all-African American dance band to receive a commercial recording contract,[236] recording "Down Home Rag" this year.[126] Europe and the Castles are best known for introducing the castle walk, turkey trot, bunny-hug, Castle rock and fox trot.[283][284]

- The Italian Luigi Russolo publishes L'arte dei rumori, "in which he (views) the evolution of modern music as parallel to that of industrial machinery", a basis for futurism, a movement "identified with technology and the urban-industrial environment... "seeking to enlarge and enrich the domain of sounds in all categories".[285] The foremost proponent of futurism in the United States is Leo Ornstein, who composes Dwarf Suite this year; it is the first of his "anarchistic" and highly dissonant pieces.[286]

- The "first black theater circuit" is founded by Sherman H. Dudley. It will lead to the creation of the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA).[287]

- Robert Nathaniel Dett becomes the first African American director of music at Hampton Institute in Virginia.[288]

- James Mundy begins founding community groups in Chicago, and staging "mammoth concerts" at the Coliseum and Orchestra Hall. Choruses led by Mundy and J. Wesley Jones will sing at "all important occasions in Chicago that called for the participation of blacks" into the 1930s, when the duo's choruses attracted wide attention for their rivalry.[161]

- Bill Johnson founds the Original Creole Orchestra featuring Freddie Keppard, who become the first African American dance band to make transcontinental tours, on the vaudeville circuit. This band carries the "jazz of New Orleans to the rest of the nation".[289]

- Harry Pace and W.C. Handy found the first black-owned music publishing firm.[131]

- Thomas Edison forms a disc company, essentially conceding to the new format rather than his long-time business of cylinders.[290]

- Billboard begins publishing information on the relative success of sheet music for various songs.[74]

- The Lyric Theater opens in Miami, soon becoming one of the pre-eminent African American music venues in the area.[291]

- The Apollo Theatre in New York opens, eventually becoming a music venue and cultural symbol of unparalleled importance in African American music.[292]

1914

- The operetta ends its period of dominating the Broadway stage.[217]

- The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) is founded to ensure that composers are paid for performances of their work.[228][293] There are 170 charter members, of whom, six are black: Will Tyers, Harry T. Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond.[185][294]

- W. C. Handy publishes "St. Louis Blues", "the most widely popular and enduring commercial success of all blues songs"[295] It will carry "the blues all over the world".[266]

- Dance is becoming a major part of social life in New York and other cities, while certain dancers become national symbols, including Vernon and Irene Castle, and Maurice Mouvet and Florence Walton.[296] The Castles' recordings are with James Reese Europe's Syncopated Society Orchestra, the first black ensemble with a recording contract.[294][297][298]

- The Boston Symphony Orchestra hosts the American premier of Arnold Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra, a composition that experimented with atonality and other new elements; the premier scandalized the musical establishment of Boston.[299]

- R. Nathaniel Dett composes and publishes one of the first "anthemized" versions of a spiritual, specifically "Listen to the Lambs".[300]

- The first permanent professional orchestra is established in Baltimore.[7]

- The Hardanger Violinist Association of America is established in Ellsworth, Wisconsin to preserve and celebrate the traditions of the Norwegian Hardanger fiddle. The Association's main activities are fiddling contests known as kappleikar.[21]

- Freddie Kreppard, a jazz cornetist, takes his Original Creole Orchestra to California, causing a popular sensation with his music, which he calls jass.[301]

- Jewish American choirs begin springing up in urban areas across the country, many of them associated with socialism.[302]

- James P. Johnson publishes "Carolina Shout", the song that will make him famous and launch his career as one of the big composers of Eastern ragtime.[277]

- Joseph Douglass becomes the first violinist to record, for the Victor Talking Machine Company, but the results are never released.[90]

- Nicola A. Montani organizes the Society of St. Gregory of America to assist in implementing the musical reforms of the Motu proprio encyclical issued by Pope Pius X in 1903.[170]

- Tom Brown becomes the first white jazz performer to leave New Orleans to make a career in Chicago.[303]

1915

| Mid-1910s music trends |

- The United States begins to become an "outpost where new European works were seldom heard into an important international center for the presentation of new music."[304]

- The creative peak of jazz in New Orleans.[305]

- English folklorist Cecil Sharp visits the United States and recruits May Gadd to form the Country Dance and Song Society of America to teach morris and country dancing in the Northeast US, including at the Pinewoods Camp near Plymouth, Massachusetts.[306]

|

- The Panama-Pacific Exposition is held in San Francisco, and Hawaiian performances lead to unprecedented interest for Hawaiian music, as well as the ukulele and the Hawaiian guitar, which eventually becomes the steel guitar used primarily in country music. The song "On the Beach at Waikiki" is usually credited with sparking the craze.[37]

- Jerome Kern receives his first "major success with a musical comedy", with Very Good Eddie with lyrics by Schuyler Greene and a libretto by Guy Bolton, based on a farce written by Phillip Bartholomae.[307]

- The score for the film The Birth of a Nation, composed by Joseph Carl Breil, launches the idea of a written film score being a musical work in its own right.[101]

- "Jelly Roll Blues" by Jelly Roll Morton becomes the first published jazz arrangement. Morton, one of the first jazz pianists,[308] will come to be regarded as "the first true jazz composer" in that he was probably the first to write down his jazz arrangements in musical notation.[309] Clarence Williams claimed to be the first to use the word jazz on sheet music, for the song "Brown Skin, Who You For?", which he described as a "Jazz Song".[234]

- Melville Charlton becomes the first African American to become an associate in the American Guild of Organists.[310]

- Marie Lucas' Famous Ladies Orchestra begins performing, soon making Lucas the best known of the "female leaders of syncopated orchestras".[209]

- Charles Demuth begins a series of jazz-themed paintings that are a "definitive contribution to the early history of jazz.[281]

- Tom Brown forms a white band, Brown's Dixieland Jass Band, for the Lamb's Club in Chicago; this dance orchestra was the first group to "formally introduce the music called jazz or jazz" to white Americans. African American ensembles did not use the word jazz consistently until the 1920s.[281]

- The Howard Theater.the most prominent African American music venue in Washington, D.C., opens.[311]

- African Americans begin moving to northern cities, especially Chicago,[312] in large numbers, bring with them their distinctive forms of music.[313]

- The founding Musical Quarterly, with Oscar Sonneck as chief editor, gives musicologists their first "specialized forum" in the country.[170]

1916

- Harry T. Burleigh arranges a series of spirituals, artistically composed to fit within the Western classical hymn and aria traditions,[258] in Jubilee Songs of the United States of America. He is the first to arrange a spiritual for solo voice,[185] and is also credited with "starting the practice of closing recitals with a group of spirituals".[177]

- Lucie Campbell becomes the music director of the National Baptist Convention's Sunday School and the Union Congress of the Baptist Young People; during her career, she will compose a number of important hymns, including "Heavenly Sunshine", "Something Within", "He Understands, He'll Say 'Well Done'" and "The King's Highway".[314]

- Victor Herbert writes the first full-length score for a motion picture, for The Fall of a Nation.[315]

- English folklorist Cecil Sharp begins collecting Scottish and English folk songs in the southern Appalachian region, and is surprised to discover that the "cult of singing (British) traditional songs is far more alive than it is in England, or has been, for fifty years or more".[227][316][317]

- The first Lithuanian American song festival is held, predating the first similar festival in Lithuania by eight years.[21]

- A bookstore in New York is opened by Myron Surmach, becoming one of the major institutions of the Ukrainian American music industry.[318]

- Irish American music's commercial recording begins in earnest with the work of Ellen O'Byrne DeWitt in Boston.[319]

- Ernest Bloch comes to America. His subsequent work will mark "the crux of the Hebraic impact in America's art music".[320]

- Sherman Clay begins publishing Hawaiian sheet music in San Francisco, greatly improving distribution for Hawaiian music on the mainland, while Ernest Ka'ai publishes a ukulele instruction book, The Ukulele: A Hawaiian Guitar and How to Play It, the first of many to come throughout the following decade.[37]

- Charles A. Tindley's New Songs of Paradise is a popular work,[321] the "first publication of a collection of gospel hymns written by a black songwriter".[185]

- Emma Azalia Hackley becomes one of the first African Americans to record, though the results are never released.[178]

- Nathaniel Clark Smith begins his teaching career at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri. He will go on to pioneer the African American "master teacher" phenomenon, in which a public school teacher contributes an "enormous amount of time to developing the skills of talented young people". Smith becomes a local legend, and his students include many of the "leading jazz and concert artists" of the mid-20th century.[322]

- John Alden Carpenter's Concertino for Piano and Orchestra is the first work by a white composer to use elements of ragtime.[323]

- W. Benton Overstreet uses the word jass (jazz) in reference to the performers he directed for the vaudevillean Estelle Harris at the Grand Theatre of Chicago.[281]

- Congress authorizes the creation of a band for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and headquarters companies.[261]

- Westfield, New Jersey is home to the first contest for students on the memorization of recording works ("music memory contests").[151]

- "When the Saints Go Marching In", a jazz standard, is published in a Baptist hymnal. Its author is Edward Boatner, who also composed "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands".[324]

1917

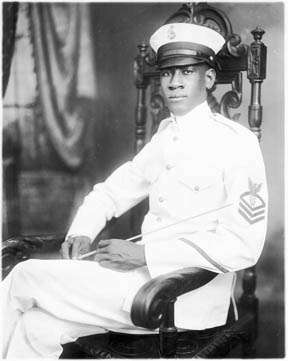

- The U.S. Navy appropriates the St. Thomas Juvenile Band, led by Alton Adams; this is the first black band and bandmaster in the Navy.[325][326][327]

- The Original Dixieland Jazz Band makes the first jazz recordings,[131][281][328][329] though the white band's style is meant for white audiences with little awareness of African American music practices, and the band is unable to impress black audiences or jazz enthusiasts.[294][330][331]

- English folk song collector Cecil Sharp publishes an anthology of songs from western North Carolina, Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians, with Olive Dame Campbell;[332] this is the "first major scholarly collection of the mountain people's music".[333]

- The October Revolution in Russia leads to political change, soon resulting in state support for professional, virtuoso balalaika orchestras; these groups come to be seen as "role models" by similar groups in the United States.[246]

- The Supreme Court rules that the "public performance of music contributed to the ability of an establishment to make profits even if no special admission was charged for that music".[73]

- With the United States' entry into World War 1, warrior customs among the Plains Native Americans are briefly revived, as many ceremonies and rituals are allowed, after many years of being banned, for the duration of the war.[2]

- Harry T. Burleigh, one of the most prominent African American composers of his time, publishes "Deep River", the first of many classically arranged spirituals.[82]

- George M. Cohan writes "Over There", which will become the most popular song of World War I.[334]

- W. Benton Overstreet's "Jazz Dance", popularized by vaudevillean Estelle Harris at Chicago's Grand Theatre, is an early use of the word jazz and is used by "more black vaudeville acts than any other song ever published".[281]

- The Navy shuts down Storyville, the prostitution district of New Orleans, because the Secretary of the Navy believed it threatened the moral integrity of the armed forces;[329] the result is an exodus of black musicians, who had played in the bars and clubs of Storyville, to cities like Memphis and Chicago.[313] Many of the musicians are hired by Northern bands because their style was considered a novelty that is thought to increase an ensemble's commercial potential; the Northerners, however, tended to adopt the "hot", bluesy style themselves.[284]

- Leo Sowerby, bandmaster of service bands during World War I composes "Tramping Tune".[327]

- W. C. Handy's band makes some of the earliest major recordings by African American artists at a session for the Columbia Phonograph Company.[263]

- The most famous riverboat bandleader of the early jazz era, Fate Marable, forms his first band. He will play with a wealth of well-remembered recording artist, though he will only play on one record, from 1924.[335]

- Art Hickman, a San Francisco bandleader, publishes "Rose Room". Hickman and his pianist-arranger, Ferde Grofé, are influential figures, who "are generally given credit for inventing the type of dance band which" dominates American popular music for the first half of the 20th century; they were among the earliest to "write separate music for the reed and brass sections, combining the higher and lower instruments in each section into choirs... for dancing rather than listening." Hickman was also probably the first to hire three saxophones, enabling the use of more complex and richer harmonies.[336]

1918

| Late 1910s music trends |

- The wind ensembles that have dominated local community bands since the Civil War begin to decline in importance.[79]

- More than 60,000 African Americans from Texas, Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana and Texas move to Chicago, especially in the city's South Side. The black population boom "ushered in the city's jazz age, widening the market for black musical entertainment", including cabarets, dance halls, and vaudeville and movie theaters.[337]

- Tin Pan Alley songwriters capitalize on the Hawaiian music fad, creating songs with thematic elements evoking Hawaii.[37]

- Stride piano grows popular in New York City.[338]

|

- The Cotton Club is founded in Harlem, soon becoming the most prominent jazz venuesof the era.[339]

- Henry Cowell, an ultramodernist, while working under Charles Seeger, writes New Musical Resources, and "important compositional and theoretical primer".[340]

- Charles N. Daniels' "Mickey (Pretty Mickey)" is one of the first pieces of music written expressly for a film, for the movie of the same name starring Mabel Normand.[73]

- The Native American Church, which uses many musical elements in its services, including peyote songs, is formally incorporated.[26]

- The first permanent professional orchestra is established in Cleveland.[7]

- The Million Dollar Theater is opened in Los Angeles, eventually becoming one of the premier avenues for Spanish language performances in the Western hemisphere.[200]

- A Kansas woman named Nora Holt becomes the first African American to complete a master's degree education in music, from the Chicago Musical College.[341]

- The Pace and Handy Music Company music publishing, a firm for African American composers, co-owned by W. C. Handy, relocates to New York and becomes a leading local institution.[342]

- Charles Tomlinson Griffes' Sonata for Piano is considered his "most original... most complex and ambitious work", and a "powerfully creative and consistently conceived work that (stands) as a peak for neo-Romantic expression in American music for piano".[343]

- Shanewis by Charles Wakefield Cadman is the "most notable" of the Native American-themed operas then popular; it will run for eight shows in two seasons, setting a new American record for opera.[344]

- James Reese Europe's band for the 369th Infantry is the only African American military band of World War 1 sent on a special mission to perform for troops on leave in Aix-les-Bains. The band performs throughout the area, and is very well received.[345] The band popularizes ragtime in France.[346][347][348]

- E. F. Goldman organizes the "first American competition for serious concert band work". Percy Grainger and Victor Herbert serve as judges.[349]

- North Dakota and Oklahoma become the first states to sponsor band contests.[349]

- Congress, on the suggestion of General John J. Pershing, authorizes the creation of twenty additional bands for the duration of World War I. Pershing also increases the size of bands to allow for full instrumentation, setting the standard lineup for future military bands, relieves bandsmen of all non-musical duties, and establishes a band school at Chaumont in France.[350]

- The first attempt to cross-promote a song and film comes from Mickey, a film whose title song, "Mickey", is written by Charles N. Daniels.[351]

1919

- Popular bandleader James Reese Europe is murdered; he becomes the first African American honored with a public funeral in New York City.[352]

- Tin Pan Alley publishes songs that spark a fad for blues-like music; these songs include syncopated foxtrots like "Jazz Me Blues", pop songs that were marketed as blues like "Wabash Blues", as well as actual blues songs.[353]

- Prohibition begins, driving the consumption of alcohol into secret clubs and other establishments, many of which became associated with the developing genre of jazz.[354]

- The first permanent orchestra is established in Los Angeles.[7][257]

- Carl Seashore's Measures of Musical Talent is a system of assessing musical aptitude that becomes widely adopted but also inspires controversy.[32][151]

- Merle Evans begins leading the Ringling-Barnum Band, becoming the most famous circus bandleader in the country, especially known for leading the other performers with one hand while simultaneously playing the cornet.[355]

- Canadian-born black composer R. Nathaniel Dett is the first to arrange a spiritual in a classical oratorio, with Chariot Jubilee.[82]

- Irving Berlin's "You Cannot Make Your Shimmy Shake on Tea" is one of many songs from the era that expressed opposition to Prohibition. Other songs, like "Drivin' Nails in My Coffin (Every Time I Drink a Bottle of Booze)" expressed support for the abolition of alcohol.[356]

- James Sylvester Scott publishes three rags, "which are among the most demanding of all published piano ragtime": "New Era Rag", "Troubadour Rag" and "Pegasus: A Classic Rag".[357]

- George Gershwin's "Swanee", performed by Al Jolson, becomes a "tremendous hit" and Gershwin's "big breakthrough".[358]

- The National Association of Negro Musicians is founded, after Nora Holt organizes a black musicians summit in Chicago.[359]

- Ryles Jazz Club opens in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It will become the oldest and most renowned jazz club in Cambridge, and the second-most in the Boston area.[360]

References

- Abel, E. Lawrence (2000). Singing the New Nation: How Music Shaped the Confederacy, 1861–1865. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0228-6.

- Bird, Christiane (2001). The Da Capo Jazz and Blues Lover's Guide to the U.S. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81034-4.

- Mellonnee V. Burnim; Portia K. Maultsby, eds. (2005). African American Music: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-94137-7.

- Birge, Edward Bailey (2007). History of Public School Music - In the United States. ISBN 1-4067-5617-2.

- Chase, Gilbert (2000). America's Music: From the Pilgrims to the Present. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00454-X.

- Crawford, Richard (2001). America's Musical Life: A History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04810-1.

- Cusic, Don (1990). The Sound of Light: A History of Gospel Music. Popular Press. ISBN 0-87972-498-6.

- Darden, Robert (1996). People Get Ready: A New History of Black Gospel Music. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1752-3.

- Davis, Francis (2003). The History of the Blues: The Roots, The Music, The People. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81296-7.

- Elson, Louis Charles (1915). The History of American Music. Macmillan & Co.

- Elson, Louis Charles (1912). University Musical Encyclopedia: Hymn, Plain Song, Chant, Mass, Requiem. The University Society.

- Erbsen, Wayne (2003). Rural Roots of Bluegrass: Songs, Stories and History. Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications. ISBN 0-7866-7137-8.

- Gedutis, Susan (2005). See You at the Hall: Boston's Golden Era of Irish Music And Dance. Mick Moloney. UPNE. ISBN 1-55553-640-9.

- Greene, Victor R. (2004). A Singing Ambivalence: American Immigrants Between Old World and New, 1830–1930. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-794-5.

- Hansen, Richard K. (2005). The American Wind Band: A Cultural History. GIA Publications. ISBN 1-57999-467-9.

- Hardie, Daniel (2002). Exploring Early Jazz: The Origins and Evolution of the New Orleans Style. iUniverse. 0595218768.

- Heskes, Irene (Winter 1984). "Music as Social History: American Yiddish Theater Music, 1882–1920". American Music: Music of the American Theater. University of Illinois Press. 2 (4): 73–87. doi:10.2307/3051563.

- Hinkle-Turner, Elizabeth (2006). Women Composers and Music Technology in the United States: Crossing the Line. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-0461-6.

- Hitchcock, H. Wiley; Stanley Sadie (1984). The New Grove Dictionary of American Music, Volume II: E - K. Macmillan Press.

- Jones, LeRoi (2002) [1963]. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. Perennial. ISBN 0-688-18474-X.

- InfoUSA. "Spotlight: Biography". Department of State. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- Klitz, Brian (June 1989). "Blacks and Pre-Jazz Instrumental Music in America". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music. Croatian Musicological Society. 20 (1): 43–60. doi:10.2307/836550.

- Kirk, Elise Kuhl (2001). American Opera. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02623-3.

- Komara, Edward M. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Blues. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92699-8.

- Koskoff, Ellen (ed.) (2000). Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 3: The United States and Canada. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-4944-6.

- Koskoff, Ellen (2005). Music Cultures in the United States: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96589-6.

- Levine, Victoria Lindsay (2002). Writing American Indian Music. American Musicological Society. ISBN 0-89579-494-2.

- Malone, Bill C.; David Stricklin (2003). Southern Music/American Music. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9055-X.

- Miller, James. Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947–1977. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80873-0.

- Moore, Allan (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00107-2.

- Lankford, Jr., Ronald D. (2005). Folk Music USA: The Changing Voice of Protest. New York: Schirmer Trade Books. ISBN 0-8256-7300-3.

- Malone, Bill C.; David Stricklin (2003). Southern Music/American Music. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9055-X.

- Nicholls, David (1998). The Cambridge History of American Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45429-8.

- Peretti, Burton W. (2008). Lift Every Voice. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-5811-8.

- Office of the Press Secretary (June 17, 2008). "President Bush Honors Black Music Month". White House. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- John Shepherd; David Horn; Dave Laing; Paul Oliver; Peter Wicke, eds. (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 1: Media, Industry and Society. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-6321-5.

- Souchon, Edmund (June–July 1957). "Jazz in New Orleans". Music Educators Journal. MENC: The National Association for Music Education. 43 (6): 42–45.

- Southern, Eileen (1997). Music of Black Americans. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-03843-2.

- Tribe, Ivan M. (2006). Country: A Regional Exploration. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-33026-3.

- Ukpokodu, Peter (May 2000). "African American Males in Dance, Music, Theater, and Film". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 569 (The African American Male in American Life and Thought): 71–85. doi:10.1177/0002716200569001006.

- "U.S. Army Bands in History". U.S. Army Bands. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

Notes

- ↑ Hinkle-Turner, pg. 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gooding, Erik D. (440–450). "Plains". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music.

- ↑ Chase, pg. 342

- ↑ Southern, pg. 242

- ↑ Hansen, pg. 223

- 1 2 3 Crawford, pg. 311

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Kearns, Williams. "Overview of Music in the United States". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 519–553.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cockrell, Dale and Andrew M. Zinck, "Popular Music of the Parlor and Stage", pgs. 179–201, in the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music

- ↑ Chase, pgs. 363–364

- ↑ Hansen, pg. 233

- 1 2 3 Crawford, pg. 383

- ↑ Chase, pg. 395 calls it the "first quasi-scientific treatise on North American Indian music".

- ↑ Levine, pg. xxxv

- ↑ Nicholls, pg. 28

- ↑ President Bush Honors Black Music Month

- 1 2 Seeger, Anthony and Paul Théberg, "Technology and Media", pgs. 235–249, in the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music

- ↑ Darden, pg. 126

- ↑ Burk, Meierhoff and Phillips, pg. 183

- 1 2 Zheng, Su. "Chinese Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 957–966.

- ↑ Heskes, pg. 86

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Levy, Mark; Carl Rahkonen and Ain Haas. "Scandinavian and Baltic Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 866–881.

- 1 2 3 Crawford, pg. 525

- ↑ Burk, Meierhoff and Phillips, pg. 229

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blum, Stephen. "Sources, Scholarship and Historiography" in the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, pgs. 21–37

- ↑ Perkins, C. C.; J. S. Dwight (1883). History of the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston, Massachusetts. Boston: Stone & Forell.

- 1 2 3 4 Levine, Victoria Lindsay; Judith A. Gray. "Musical Interactions". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 480–490.

- ↑ Reyes, Adelaida. "Identity, Diversity, and Interaction". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 504–518.

- ↑ Southern, pg. 237

- 1 2 Bastian, Vanessa. "Instrument Manufacture". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 526–529.

- ↑ Clarke, pg. 62

- ↑ Elson, pg. 116

- 1 2 3 4 Campbell, Patricia Sheehan and Rita Klinger, "Learning", pgs. 274–287, in the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music

- ↑ Birge, pg. 139

- 1 2 Asai, Susan M. "Japanese Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 967–974.

- ↑ Birge, pg. 133

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 437

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stillman, Amy Ku'uleialoha. "Polynesian Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 1047–1053.

- ↑ Koskoff, pg. 130

- ↑ Chase, pg. 415; Chase indicates that the year, 1885, is approximate.

- ↑ Southern, pg. 324; Southern does not refer to any ambiguity in the year of Joplin's arrival in St. Louis.

- ↑ Southern, pgs. 324–325

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kirk, pg. 386

- ↑ Laing, Dave; David Sanjek and David Horn. "Music Publishing". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music. pp. 595–599.

- 1 2 Romero, Brenda M. "Great Basin". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 420–427.

- ↑ Chase, pg. 323

- 1 2 Laing, Dave. "Berne Convention". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 480–481.

- ↑ Southern, pg. 309

- 1 2 Linehan, Andrew. "Soundcarrier". Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 359–366.

- ↑ Heskes, pg. 75

- ↑ Gronow, Pekka. "Phonograph". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 517–518.

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 604

- ↑ Malone and Stricklin, pg. 29

- ↑ Chase, pg. 383

- ↑ Greene, pg. 97

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 373

- ↑ Matthews, W. S. B. (1889). A Hundred Years of Music in America. Chicago: G. L. Howe.

- 1 2 Riis, Thomas L. "Musical Theater". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 614–623.

- ↑ Chase, pg. 324

- ↑ Chase, pg. 398

- ↑ Southern, pg. 288

- 1 2 3 Clarke, pg. 229

- ↑ Laing, Dave. "Jukebox". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 513–515.

- ↑ Laing, Dave; Paul Oliver. "Catalog". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. p. 535.

- 1 2 Crawford, pg. 352

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 389

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 471

- ↑ Oliver, Paul. "Field Recording". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Southern, pg. 301

- ↑ Birge, pg. 142

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 449

- 1 2 3 Crawford, pg. 497

- 1 2 Bird, pg. 133

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sanjek, David and Will Straw, "The Music Industry", pgs. 256–267, in the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music

- 1 2 Horn, David; David Sanjek. "Sheet Music". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music. pp. 599–605.

- ↑ Tillman's Revival songbook for 1891, where it appears as Item 223.

- ↑ Southern, pg. 267

- ↑ Hardie, pg. 175; Hardie notes some doubt about Laine's claims, but acknowledges that Laine is a key figure in the transition to white jazz.

- ↑ Bird, pg. 24

- 1 2 Crawford, pg. 455

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 479

- ↑ Chase, pg, 337

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wright, Jacqueline R. B. "Concert Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 603–613.

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 484

- ↑ Gates and Appiah, pg. 560

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 396

- ↑ Chase, pg. 396

- ↑ Clarke, pg. 58

- ↑ Southern, pg. 329

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 539

- 1 2 Southern, pg. 283

- ↑ Caldwell Titcomb (Spring 1990). "Black String Musicians: Ascending the Scale". Black Music Research Journal. Center for Black Music Research - Columbia College Chicago and University of Illinois Press. 10 (1): 107–112. doi:10.2307/779543. JSTOR 779543.

- ↑ Diamond, Beverly; Barbara Benary. "Indonesian Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 1011–1023.

- 1 2 Rasmussen, Anne K. "Middle Eastern Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 1028–1041.

- ↑ Clarke, pg. 16

- ↑ Darden, pg. 7

- ↑ Burk, Meierhoff and Phillips, pg. 284

- ↑ Burnim and Maultsby, pg. 11

- ↑ Maultsby, Portia K.; Mellonee V. Burnin and Susan Oehler. "Overview". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 572–591.

- ↑ Erbsen, pg. 134

- 1 2 3 Chase, pg. 384

- 1 2 Steiner, Fred; Martin Marks. "Film music". New Grove Dictionary of Music, Volume II: E - K.

- 1 2 3 Southern, pg. 343

- ↑ Darden, pg. 148

- ↑ Darden, pg. 156

- ↑ Chase, pg. 352

- 1 2 Malone and Stricklin, pg. 10

- ↑ Southern, pg. 344

- ↑ Marks, Edward B.; A.J. Liebling (1934). They All Sang: from Tony Pastor to Rudy Vallee. The Viking Press. p. 321.

- ↑ "Music Video 1900 Style". PBS. 2004. Archived from the original on 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ↑ Sanjek, David. "E. B. Marks". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music. pp. 588–589.

Sanjek specifically names Bob Cole, James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson

- ↑ Darden, pg. 128

- 1 2 Chase, pg. 397

- ↑ Chase, pg. 370

- ↑ Hilts, Janet; David Buckley and John Shepherd. "Crime". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 189–196.

- ↑ Chase, pg. 371

- 1 2 3 Southern, pg. 221

- ↑ Schrader, Barry. Electroacoustic music. New Grove Dictionary of American Music. pp. 30–35.

- ↑ Laing, Dave. "Musicians' Unions". The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. pp. 785–787.

- ↑ Crawford, pgs. 381–382

- ↑ Chase, pg. 345

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 476

- ↑ Crawford, pgs. 540–541

- ↑ Clarke, pg. 59

- ↑ Miller, Terry, "Religion", pgs. 116–128, in the Garland Encyclopedia of Music

- ↑ Southern, pg. 317

- 1 2 3 4 Monson, Ingrid. "Jazz". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 650–666.

- ↑ Southern, pg. 320

- ↑ Erbsen, pg. 124

- ↑ Struble, pg. 36

- ↑ Chase, pg. 392

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moore, pg. xii

- ↑ Hansen, pg. 240

- 1 2 Hansen, pg. 241

- 1 2 Bergey, Barry, "Government and Politics", pgs. 288–303, in the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music

- 1 2 Peretti, pg. 50

- ↑ Bird, pg. 28

- ↑ Malone and Stricklin, pg. 52

- ↑ Jones, pgs. 144–145

- ↑ Chase, pg. 337