American Federation of Musicians

.png) | |

| Full name | American Federation of Musicians of the United States and Canada |

|---|---|

| Founded | October 19, 1896 |

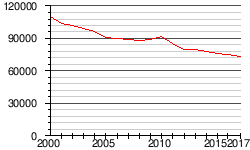

| Members | 73,617 (2017)[1] |

| Affiliation | AFL–CIO, CLC |

| Key people | Raymond M. Hair Jr., President |

| Office location | New York City, United States |

| Country | United States, Canada |

| Website |

www |

The American Federation of Musicians of the United States and Canada (AFM/AFofM) is a 501(c)(5)[2] labor union representing professional musicians in the United States and Canada. The AFM, which has its headquarters in New York City, is led by president Raymond M. Hair, Jr. Founded in Cincinnati in 1896 as the successor to the "National League of Musicians," the AFM is the largest organization in the world to represent professional musicians. They negotiate fair agreements, protect ownership of recorded music, secure benefits such as health care and pension, and lobby legislators. In the US, it is the American Federation of Musicians (AFM)—and in Canada, the Canadian Federation of Musicians/Fédération canadienne des musiciens (CFM/FCM).[3] The AFM is affiliated with AFL–CIO, the largest federation of Unions in the United States; and the Canadian Labour Congress, the federation of unions in Canada.[4][5]

Among the most famous AFM actions was the 1942–44 musicians' strike, to pressure record companies to agree to a better arrangement for paying royalties.

History

The American Federation of Labor recognized the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) in 1896. In 1900, the American Federation of Musicians modified its name to "American Federation of Musicians of the United States and Canada".

The downfall of the 1900s

In the early 1900s, record companies produced recordings and musicians profited. However, around World War I, general unemployment also affected musicians. Movies displaced some traditional entertainments, and were silent films. Because of that, the declining economy, and other factors, many musicians were laid off.

The Musical Mutual Protective Union of New York became Local 301 of the American Federation of Musicians in 1902.[6] In 1904, the local had 5,000 members, who were almost entirely German.[7][8] In 1910, approximately 300 black musicians were members in the roughly 8,000-member local.[9] The local lost its charter and was disbanded in 1921.[6]

By the end of the 1920s, many factors had reduced the number of recording companies. As the nation recovered from World War I, technology advanced and there was diversity in recording and producing music. This encouraged the American Federation of Musicians. AFM was motivated to bring music awareness of music to the public. In 1938, the American Federation of Musicians established signed an agreement with motion pictures companies.

Among the most famous AFM actions was the 1942–44 musicians' strike, to pressure record companies to agree to a royalty system more beneficial to the musicians. This was sometimes called the "Petrillo ban", because James Petrillo was the newly elected head of the union.[10] Petrillo organized a second recording ban in 1948 (from January 1 to December 14), in response to the Taft–Hartley Act.

Birth to a new generation, 1960s

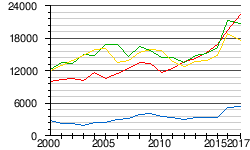

The early 1960s marked a new beginning to the music industry. Rock and roll became mainstream in the 1960s. After the Second World War, American culture entered the baby boom era. Rock and roll brought an explosion to the music industry market. It became "mainstream" music, proving its popularity through record sales.

By 1970s, North American music had divided into more genres than ever before. As more genres were entered the market, record sales accelerated as well. Earlier genres such as classical, jazz, and rhythm and blues contributed to new sounds such as gospel, rap, and hip hop.

21st century, New millennium

At the AFM convention in Las Vegas on June 23, 2010, the AFM elected Ray Hair for a three-year term as president.[11] Hair was re-elected for an additional three years in July 2013.[12] He was elected for a third term in June 2016.[13]

The AFM is active in trying to prevent plagiarism and illegal downloading. The sheer volume of recording industry output contributes to the possibility that songs might overlap in sound, melody, or other details of composition. Also, as the Internet and technology advances and becomes easily accessible, it is easier for people to share the music online.

Departments

There are several AFM departments:

- Administration offices (Presidents, Secretary)

- Education

- Symphonic

- Legislative

- International

- Immigration

Locations

The American Federation of Musicians headquarters is in New York City, it has branches in Los Angeles, Hawaii, Washington, Toronto, and hundreds of small branches in smaller cities throughout the United States and Canada.

Composition

According to the AFM's Department of Labor records since 2006, when membership classification was first reported, around 81%, or three quarters, of the union's membership are "regular" members, who are eligible to vote for the union. In addition to the other voting eligible "life" and "youth" classifications, the "inactive life" members have the rights of active union members except that "they shall not be allowed to vote or hold office" according to the bylaws in exchange for the rate less than "life" members.[14] As of 2017, this accounted for 61,907 "regular members" (84% of total), 10,509 "life" members (14%), 641 "inactive life" members (1%) and 560 "youth" members (1%).[1]

Leadership

As of 2017, the president of the AFM is Ray Hair. As of 2016, the executive committee consisted of the following AFM members: John Acosta, Tino Gagliardi, Tina Morrison, Joe Parente and Dave Pomeroy.[15]

Presidents

- 1896–1900 Owen Miller

- 1900–1914 Joseph Weber

- 1914–1915 Frank Carothers

- 1915–1940 Joseph Weber

- 1940–1958 James C. Petrillo

- 1958–1970 Herman D. Kenin

- 1970–1978 Hal Davis

- 1978–1987 Victor Fuentealba

- 1987–1991 Martin Emerson

- 1991–1995 Mark Massagli

- 1995–2001 Steve Young

- 2001–2010 Tom Lee

- 2010–present Ray Hair

References

- 1 2 US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-207. Report submitted March 29, 2018.

- ↑ "Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax". American Federation of Musicians of the United States and Canada. Guidestar. December 31, 2015.

- ↑ "About AFM". American Federation of Musicians. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Unions of the AFL-CIO". AFL-CIO. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Canadian Labour Congress Affiliated Unions". Congress of Union Retirees in Canada. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- 1 2 Gray, Christopher (June 6, 1999). "Streetscapes /Readers' Questions; Echoes of a Union Hall; Artificial Sunlight". The New York Times. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ↑ Koegel, John (2009). Music in German Immigrant Theater: New York City, 1840–1940. University Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1580462150. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ↑ Toff, Nancy (2005). Monarch of the Flute: The Life of Georges Barrere. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195346923. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ↑ Goldberg, Jacob (February 11, 2013). "Breaking the color line | Associated Musicians of Greater New York". Allegro. 113 (2). Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books Limited. p. 13. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- ↑ "Ray Hair Elected President of AFM at Vegas Convention". Film Music Magazine. June 23, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ↑ Handel, Jonathan (July 26, 2013). "American Federation of Musicians' President Ray Hair Re-Elected". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ↑ "Ray Hair Re-Elected International President at AFM's 100th Convention" (Press release). American Federation of Musicians. June 24, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- 1 2 3 US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-207. (Search)

- ↑ "Our Leaders". American Federation of Musicians. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

Further reading

- Michael James Roberts, Tell Tchaikovsky the News: Rock 'n' Roll, the Labor Question, and the Musicians' Union, 1942–1968. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-8223-5463-5 .

External links

- Official website

- Musicians' Association of Seattle Records. 1905–2010. 5.52 cubic feet (7 boxes).

- David Keller manuscript of The Blue Note: Seattle's Black Musician's Union, A Pictorial History. 2000. .21 cubic ft (1 box)

- Novak, Matt (February 10, 2012). "Musicians Wage War Against Evil Robots". Smithsonian. Retrieved 10 February 2017.