Timeline of international trade

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

The history of international trade chronicles notable events that have affected the trade between various countries.

In the era before the rise of the nation state, the term 'international' trade cannot be literally applied, but simply means trade over long distances; the sort of movement in goods which would represent international trade in the modern world.

In the 21st century, China, the European Union and the United States are the three largest trading markets in the world.[1]

Chronology of events

Ancient

- Records from the 19th century BCE attest to the existence of an Assyrian merchant colony at Kanesh in Cappadocia.[2]

- The domestication of camel allows Arabian nomads to control long distance trade in spices and silk from the Far East.[3]

- The Egyptians trade in the Red sea, importing spices from the "Land of Punt" and from Arabia.[4]

- Indian goods are brought in Arabian vessels to Aden.[4]

- The "ships of Tarshish", a Tyrian fleet equipped at Ezion Geber, make several trading voyages to the East bringing back gold, silver, ivory and precious stones.[4]

- Tiglath-Pileser III attacks Gaza in order to control trade along the Incense Route.[5]

- The Greek Ptolemaic dynasty exploits trading opportunities with India prior to the Roman involvement.[6]

- The cargo from the India and Egypt trade is shipped to Aden.[6]

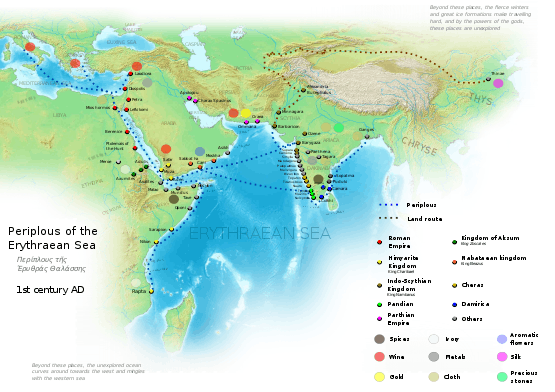

Roman trade with India according to the Periplus Maris Erythraei, 1st century CE.

- The Silk Road is established after the diplomatic travels of the Han Dynasty Chinese envoy Zhang Qian to Central Asia, with Chinese goods making their way to India, Persia, and the Roman Empire, and vice versa.

- With the establishment of Roman Egypt, the Romans initiate trade with India.[7]

- The goods from the East African trade are landed at one of the three main Roman ports, Arsinoe, Berenice or Myos Hormos.[8]

- Myos Hormos and Berencie (rose to prominence during the 1st century BCE) appear to have been important ancient trading ports.[7]

- Gerrha controls the Incense trade routes across Arabia to the Mediterranean and exercises control over the trading of aromatics to Babylon in the 1st century BC.[9] Additionally, it served as a port of entry for goods shipped from India to the East.[9]

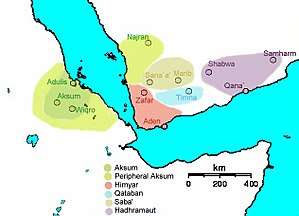

- Due to its prominent position in the incense trade, Yemen attracts settlers from the fertile crescent.[10]

The economy of the Kingdom of Qataban (light blue) was based on the cultivation and trade of spices and aromatics including frankincense and myrrh. These were exported to the Mediterranean, India and Abyssinia where they were greatly prized by many cultures, using camels on routes through Arabia, and to India by sea.

- Pre-Islamic Meccans use the old Incense Route to benefit from the heavy Roman demand for luxury goods.[11]

- In Java and Borneo, the introduction of Indian culture creates a demand for aromatics. These trading outposts later serve the Chinese and Arab markets.[12]

- Following the demise of the incense trade Yemen takes to the export of coffee via the Red Sea port of al-Mocha.[13]

Middle Ages

- The Abbasids use Alexandria, Damietta, Aden and Siraf as entry ports to India and China.[14]

- At the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, the Tang Dynasty Chinese capital at Chang'an becomes a major metropolitan center for foreign trade, travel, and residence. This role would be assumed by Kaifeng and Hangzhou during the Song Dynasty.

- Guangzhou was China's greatest international seaport during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), but its importance was eclipsed by the international seaport of Quanzhou during the Song Dynasty (960–1279).

- Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden pay tribute in form of musk, camphor, ambergris and sandalwood to Ibn Ziyad, the sultan of Yemen.[14]

- Indian exports of spices find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850), al-Ghafiqi (1150), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (14th century).[15]

- The Hanseatic League secures trading privileges and market rights in England for goods from the League's trading cities in 1157.

Early modern

This figure illustrates the path of Vasco da Gama heading for the first time to India (black) as well as the trips of Pêro da Covilhã (orange) and Afonso de Paiva (blue). The path common to both is the green line.

- Due to the Turkish hold on the Levant during the second half of the 15th century the traditional Spice Route shifts from the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea.[16]

- In 1492 a Spanish expedition commanded by Christopher Columbus arrive in America.

- Portuguese diplomat Pero da Covilha (1460 – after 1526) undertakes a mission to explore the trade routes of the Near East and the adjoining regions of Asia and Africa. The exploration commenced from Santarém (1487) to Barcelona, Naples, Alexandria, Cairo and ultimately to India.

- Portuguese explorer and adventurer Vasco da Gama is credited with establishing another sea route from Europe to India.

- In the 1530s, the Portuguese ship spices to Hormuz.[17]

- Japan introduced a system of foreign trade licenses to prevent smuggling and piracy in 1592.

- The first Dutch expedition left from Amsterdam (April 1595) for South East Asia.[18]

- A Dutch convoy sailed in 1598 and returned one year later with 600,000 pounds of spices and other East Indian products.[18]

- The Dutch East India Company is formed in 1602.

- The first English outpost in the East Indies is established in Sumatra in 1685.

- Japan introduces the closed door policy regarding trade(Japan was sealed off to foreigners and only very selective trading to the Dutch and Chinese was allowed) 1639.

- The 17th century saw military disturbances around the Ottawa river trade route.[19] During the late 18th century, the French built military forts at strategic locations along the main trade routes of Canada.[20] These forts checked the British advances, served as trading posts which included the Native Americans in fur trade and acted as communications posts.[20]

- In 1799, The Dutch East India company, formerly the world's largest company goes bankrupt, partly due to the rise of competitive free trade.

Later modern

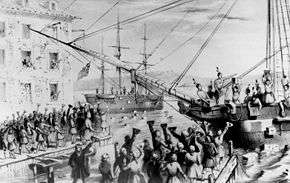

Monopolistic activity by the company triggered the Boston Tea Party.

- Japan is served by the Portuguese from Macao and later by the Dutch.[17]

- Despite the late entry of the United States into the spice trade, merchants from Salem, Massachusetts trade profitably with Sumatra during the early years of the 19th century.[21]

- In 1815, the first commercial shipment of nutmegs from Sumatra arrived in Europe.[22]

- Grenada becomes involved in the spice trade.[22]

- The Siamese-American Treaty of 1833 calls for free trade, except for export of rice and import of munitions of war.

- Opium War (1840) – Britain invades China to overturn the Chinese ban on opium imports.

- Britain unilaterally adopts a policy of free trade and abolishes the Corn Laws in 1846.[23]

- The first international free trade agreement, the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty, is finalised in 1860 between the United Kingdom and France, prepared by Richard Cobden and Michel Chevalier; it sparks off successive agreements between other countries in Europe.[23]

- The Japanese Meiji Restoration (1868) leads the way to Japan opening its borders and quickly industrialising through free trade. Under bilateral treaties restraint of trade imports to Japan were forbidden.

- In 1873, the Wiener Börse slump signals the start of the continental Long Depression, during which support for protectionism grows.

Post-World War II

- In 1946. the Bretton Woods system goes into effect; it had been planned since 1944 as an international economic structure to prevent further depressions and wars. It included institutions and rules intended to prevent national trade barriers being erected, as the lack of free trade was considered by many to have been a principal cause of war.

- In 1947, 23 countries agree to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade to rationalize trade among the nations.

- In Europe, six countries form the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951, the first international organisation to be based on the principles of supranationalism.

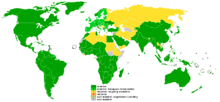

A world map of WTO participation:

Members

Members, dually represented with the European Union

Observer, ongoing accession

Observer

Non-member, negotiations pending

Non-member

- The European Economic Community (EEC) is established by the Inner Six European countries with a common commercial policy in 1957.

- The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is established in 1960 as a trade bloc-alternative by the Outer Seven European countries who did not join the EEC.

- Four important ISO (International Organization for Standardization) recommendations standardized containerization globally:[24]

- January 1968: R-668 defined the terminology, dimensions and ratings

- July 1968: R-790 defined the identification markings

- January 1970: R-1161 made recommendations about corner fittings

- October 1970: R-1897 set out the minimum internal dimensions of general purpose freight containers

- The Zangger Committee is formed in 1971 to advise on the interpretation of nuclear goods in relation to international trade and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

- 16 October 1973: OPEC raises the Saudi light crude export price, and mandate an export cut the next day, plus an Embargo on oil exports to nations allied with Israel in the course of the Yom Kippur War. (also see Oil crisis)

- The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) was created in 1974 to moderate international trade in nuclear related goods, after the explosion of a nuclear device by a non-nuclear weapon State.

- The breakdown of the Soviet Union leads to a reclassification of within-country trade to international trade, which has a small effect on the rise of international trade.[25]

- After expanding its membership to 12 countries, the European Economic Community becomes the European Union (EU) on 1 November 1993.[nb 1]

- 1 January 1994: The European Economic Area (EEA) is formed to provide for the free movement of persons, goods, services and capital within the internal market of the European Union as well as three of the four member states of the European Free Trade Association.[nb 2]

- 1 January 1994: the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) takes effect.

- 1 January 1995: World Trade Organization is created to facilitate free trade, by mandating mutual most favored nation trading status between all signatories.

- 1 January 2002: Twelve countries of the European Union launch the Euro zone (euro in cash), which instantly becomes the second most used currency in the world.

- 2008-2009 : during the Great Trade Collapse, a drop of world GDP of 1% surprisingly caused a drop of international trade of 10%.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The twelve countries are Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

- ↑ The three EFTA member states are Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. The fourth EFTA member, Switzerland, did not joined the EEA, and instead negotiated a series of bilateral agreements with the EU over the next decade which allow it also to participate in the internal market.

References

Citations

- ↑ "EU position in world trade". European Commission. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Stearns 2001: 37

- ↑ Stearns 2001: 41

- 1 2 3 Rawlinson 2001: 11–12

- ↑ Edwards 1969: 330

- 1 2 Young 2001: 19

- 1 2 Shaw 2003: 426

- ↑ O'Leary 2001: 72

- 1 2 Larsen 1983: 56

- ↑ Glasse 2001: 59

- ↑ Crone 2004: 10

- ↑ Donkin 2003: 59

- ↑ Colburn 2002: 14

- 1 2 Donkin 2003: 91–92

- ↑ Donkin 2003: 92

- ↑ Tarling 1999: 10

- 1 2 Donkin 2003: 170

- 1 2 Donkin 2003: 169

- ↑ Easterbrook 1988: 75

- 1 2 Easterbrook 1988: 127

- ↑ Corn 1999: 265 "The first few years of the nineteenth century were the most profitable in Salem's pepper trade with Sumatra ... The peak was reached in 1805 ... Americans had entered the spice game late in the day ... Even so, the Salemites had come into the pepper trade with sufficient vigor to establish what amounted to a monopoly.

- 1 2 Corn 1999: 217 "The first commercial shipment of Sumatran nutmegs reaching Europe in 1815 ... Similar experiments were tried in ... as well as Grenada in the West Indies. The tests were successful to the point where by the mid-nineteenth century these upstart colonies collectively rivaled Banda's exports.

- 1 2 International Monetary Fund Research Dept. (1997). World Economic Outlook, May 1997: Globalization: Opportunities and Challenges. International Monetary Fund. p. 113. ISBN 9781455278886.

- ↑ Rushton, A., Oxley, J., Croucher, P. (2004). The Handbook of Logistics and Distribution Management. Kogan Page: London.

- ↑ Roser, Max; Crespo-Cuaresma, Jesus (2012). "Borders Redrawn: Measuring the Statistical Creation of International Trade". World Economy. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2012.01454.x.

Bibliography

- Stearns, Peter N.; William L. Langer (24 September 2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

- Rawlinson, Hugh George (2001). Intercourse Between India and the Western World: From the Earliest Times to the Fall of Rome. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1549-2.

- Donkin, Robin A. (2003). Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87169-248-1.

- Easterbrook, William Thomas (1988). Canadian Economic History. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6696-8.

- Young, Gary Keith (2001). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC – AD 305. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24219-3.

- Corn, Charles (1999) [First published 1998]. The Scents of Eden: A History of the Spice Trade. Kodansha America. ISBN 1-56836-249-8.

- Larsen, Curtis (1983). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarcheology of an Ancient Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46906-9.

- Crone, Patricia (2004). Meccan Trade And The Rise Of Islam. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 1-59333-102-9.

- Edwards, I. E. S.; et al. (1969). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66369-5.

- O'Leary, De Lacy (2001). Arabia Before Muhammad. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23188-4.

- Colburn, Marta (2002). The Republic Of Yemen: Development Challenges in the 21st Century. Progressio. ISBN 1-85287-249-7.

- Glasse, Cyril (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0-7591-0190-6.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Morton, Scott and Charlton Lewis (2005). China: Its History and Culture: Fourth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

- Krugman, Paul., 1996 Pop Internationalism. Cambridge: MIT Press,

- Mill, John Stuart., 1844 Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy

- Mill, John Stuart., 1848 Principles of Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy (Full text)

- Smith, A. 1776, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

External links

- The BBC's illustrated history of free trade

- Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities: a dictionary of trade in Britain, 1550–1820. Part of British History Online, by permission of the University of Wolverhampton.

This article is issued from

Wikipedia.

The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.