The Iron Bridge

| The Iron Bridge | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The Iron Bridge | |

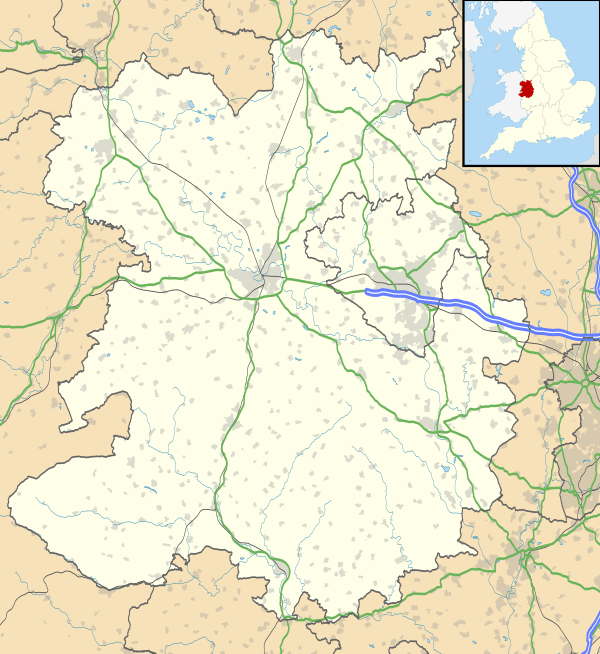

| Coordinates | 52°37′38″N 2°29′08″W / 52.627245°N 2.485533°WCoordinates: 52°37′38″N 2°29′08″W / 52.627245°N 2.485533°W |

| Carries | Pedestrian traffic |

| Crosses | River Severn |

| Locale | Ironbridge Gorge near Coalbrookdale |

| Heritage status | Grade I listed |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | cast iron arch bridge |

| Longest span | 100 ft 6 in (30.63 m) |

| History | |

| Construction start | November 1777 |

| Construction end | July 1779 |

| Opened | 1 January 1781 |

| |

The Iron Bridge is a bridge that crosses the River Severn in Shropshire, England. Opened in 1781, it was the first major bridge in the world to be made of cast iron, and was greatly celebrated after construction owing to its use of the new material.[1]

In 1934 it was designated a Scheduled Ancient Monument and closed to vehicular traffic.[1] Tolls for pedestrians were collected until 1950, when ownership of the bridge was transferred to Shropshire County Council. It now belongs to Telford and Wrekin Borough Council. The bridge, the adjacent settlement of Ironbridge and the Ironbridge Gorge form the UNESCO Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site.[2] The bridge is a Grade I listed building, and a waypoint on the South Telford Heritage Trail.[3]

History

Background

Abraham Darby I first smelted local iron ore with coke made from Coalbrookdale coal in 1709, and in the coming decades Shropshire became a centre for industry due to the low price of fuel from local mines.[4] The River Severn was used as a key trading route, but it was also a barrier to travel around the deep Severn Gorge, especially between the then important industrial parishes of Broseley and Madeley, the nearest bridge being at Buildwas two miles away.[5][6] The iron bridge was therefore proposed to link the industrial town of Broseley with the smaller mining town of Madeley and the industrial centre of Coalbrookdale. The use of the river by boat traffic and the steep sides of the gorge meant that any bridge should ideally be of a single span, and sufficiently high to allow tall ships to pass underneath.[6][7] The steepness and instability of the banks was problematic for building a bridge, and there was no point where roads on opposite sides of the river converged.[8]

The Iron Bridge was the first of its kind to be constructed, although not the first to be considered or the first iron bridge of any kind. An iron bridge was partly constructed at Lyons in 1755, but was abandoned for reasons of cost,[9] and a 72-foot-10-inch (22.2 m) span wrought iron footbridge over an ornamental waterway was erected in Yorkshire in 1769.[10]

Proposal

In 1773, architect Thomas Farnolls Pritchard wrote to his 'iron mad' friend and local ironmaster, John Wilkinson of Broseley, to suggest building a bridge out of cast iron.[11] Pritchard had previous experience with the design of both wooden and stone bridges, and it is possible that he had integrated into these designs elements of iron.[12]

During the winter of 1773–74, local newspapers advertised a proposal to petition Parliament for leave to construct an iron bridge with a single 120-foot (37 m) span.[13] In 1775, a subscription of between three and four thousand pounds was raised, and Abraham Darby III, the grandson of Abraham Darby I and an ironmaster working at Coalbrookdale, was appointed treasurer to the project.[13]

In March 1776, the Act to build a bridge received Royal Assent. It had been drafted by Thomas Addenbrooke, secretary of the trustees, and John Harries a London barrister[lower-roman 1] then presented to the House of Commons by Charles Baldwyn, MP for Salop.[14] Abraham Darby III was commissioned to cast and build the bridge.[6][15] In May 1776, the trustees withdrew Darby's commission, and instead advertised for plans for a single arch bridge to be built in "stone, brick or timber".[16] No satisfactory proposal was made, and the trustees agreed to go with Pritchard's design, but there was continued uncertainty about the use of iron, and conditions were set on the cost and duration of the construction.[16] In July 1777 the span of the bridge was decreased to 90 feet (27 m), and then increased again to 100 feet 6 inches (30.63 m), possibly in order to accommodate a towpath.[17][lower-roman 2]

Construction

The site, adjacent to where a ferry had run between Madeley and Benthall, was chosen for its high approaches on each side and the relative solidity of the ground.[6] The Act of Parliament described how the bridge was to be built from a point in Benthall parish near the house of Samuel Barnett to a point on the opposite shore near the house of Thomas Crumpton.[18] Pritchard died on 21 December 1777 in his towerhouse at Eyton on Severn, only a month after work had begun, having been ill for over a year.[6][11][19]

The masonry and abutments were constructed between 1777 and 1778, and the ribs were lifted into place in the summer of 1779 by the use of wooden derricks and cranes.[20][21] The bridge first spanned the river on 2 July 1779, and it was opened to traffic on 1 January 1781.[22][23]

More information about how the bridge was built came from the discovery in 1997 of a small watercolour by Elias Martin in a Stockholm museum, which shows the bridge under construction in 1779.[22] A half-size replica of the main section of the bridge was built in 2001 as part of the research for the BBC's Timewatch programme, which was shown the following year.[22][24]

Unusually the bridge was left incomplete: it is missing two of its lower arch sections on the town side. These sections were cast and added much later, however they were cast hollow and not solid, as the rest of the bridge is, pointing to their completion work as being more of an aesthetic than necessary exercise.

Design

The bridge is to a carpenters' design typically used for wood structures, built from five sectional cast-iron ribs that give a span of 100 feet 6 inches (30.63 m).[21] Exactly 378 long tons 10 cwt (847,800 lb or 384.6 t) of iron was used in the construction of the bridge, and there are almost 1,700 individual components, the heaviest weighing 5.5 long tons (5.6 tonnes).[21][25] Components were cast individually to fit with each other, rather than being of standard sizes, with discrepancies of up to several centimetres between 'identical' components in different locations.[26]

Decorative rings and ogees between the structural ribs of the bridge suggest that the final design was Pritchard's, as the same elements appear in a gazebo he rebuilt.[20][27] A foreman at the foundry, Thomas Gregory, drew the detailed designs for the members, resulting in the use of carpentry jointing details such as mortise and tenon joints and dovetails.[6][21][28]

Two supplemental arches, of similar cast iron construction, carry a towpath on the southern bank and also act as flood arches. A stone arch carries a small path on the northern (town side) bank.

Cast iron

The Iron Bridge is made of cast iron, which is not a good structural material for handling tension or bending moments because of its brittleness and relatively low tensile strength compared to steel and wrought iron. In a few instances bridges and buildings built with cast iron failed. Cast iron has good compressive strength and was successfully used for certain structural components in well designed old bridges and buildings. Puddled wrought iron, which was introduced after the Iron Bridge was constructed, was a much better structural material. Puddled iron became widely available after 1800 and eventually became the preferred material for bridges, rails, ships and buildings until new steel making processes were developed in the late 19th century.

Analysis of an arch and a strut from the Iron Bridge revealed the following elemental compositions:

Element Proportion Arch Strut Carbon 2.65% 3.25% Silicon 1.22% 1.48% Manganese 0.46% 1.05% Sulphur 0.102% 0.037% Phosphorus 0.54% 0.54%

The presence of 0.1% sulphur in cast iron is at the upper limit of what have been acceptable; however, some of this sulphur was rendered harmless because of the manganese present. Also, the phosphorus levels were high.[29]

Cost

Darby had agreed to construct the bridge with a budget of £3,250 (equivalent to £380,000 in 2016) and this was raised by subscribers to the project, mostly from Broseley. While the actual cost of the bridge is unknown, contemporary records suggest it was as high as £6,000 (equivalent to £701,000 in 2016), the excess being borne by Darby, who was highly indebted from other ventures as well.[30] However, by the mid-1790s the bridge was highly profitable, and tolls were giving the shareholders an annual dividend of 8 per cent.[31]

Later history

The opening of the bridge resulted in changes in the pattern of settlement in the gorge, and roads around the bridge were improved in the years after its construction.[32] The town of Ironbridge, taking its name from the bridge, developed at the northern end.[32] The trustees, as well as local hotel keepers and coach operators, promoted interest in the bridge among members of high society.[32]

Repairs

In July 1783, a 35-yard (32 m) wall was built in order to prevent the north bank from slipping into the river.[33] Cracks were found in the stone land arch on the south side in December 1784, and the neighbouring abutment showed signs of movement.[21] The Gorge is very prone to landslides, and over 20 are recorded in the British Geological Survey's National Landslide Database in the area.[34] It was suspected that the sides of the gorge were moving towards the river, forcing the feet of the arch towards each other, and consequently repairs were carried out in 1784, 1791 and 1792.[21][33]

It was the only bridge on the River Severn to survive the flood of February 1795 undamaged, due to its strength and small profile against the floodwaters.[35] The medieval bridge at Buildwas was replaced with a cast iron bridge by Thomas Telford, which, by virtue of superior design, required half the quantity of iron despite a longer span of 128 feet (39 m).[36][37] The Buildwas bridge survived until 1906.[36]

In 1800 the trustees commissioned repairs which lasted for several years, which involved the replacement of the stone land arches with wooden ones to relieve pressure on the main span.[21][33] A proposal to build a rigid support between the abutments to keep them apart was found to be impossible with the available technology, but was achieved during the later restoration of the bridge in the 1970s.[38] In 1812, its construction was described as "very bad" by Charles Hutton, and he predicted that it would not last for long, "though not from any deficiency in the iron-work."[39] The timber arches were replaced with cast iron ones in December 1820, and further repairs were necessary throughout the remainder of the 19th century.[21][40]

On 24 August 1902, a 30-foot (9.1 m) length of parapet collapsed into the river, and a section of deck plate weighing around 5 long hundredweight (250 kg) fell from the bridge in July 1903.[40] The opening of a toll-free concrete bridge in 1909 caused concern among the trustees, but it continued to be used by vehicles and pedestrians.[41][42]

Closure

A 1923 report by Mott, Hay and Anderson suggested that other than the paintwork, the main span of the bridge was in good condition. It was suggested that the metal deck of the bridge was dangerously heavy, and that after removing the dead weight the bridge should be reopened to vehicles no heavier than 2 tons and restricted to the centre of the roadway.[43] A weight limit of 4 tons was imposed, but the housing boom of the 1930s meant that drivers distributing tiles produced at Jackfield were insistent that they should be allowed to use the bridge, so the trustees took the decision to close the bridge to vehicular traffic with effect from 18 June 1934.[43] That same year, it was designated a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[21] Tolls for pedestrians were collected until 1950, when ownership of the bridge was transferred to Shropshire County Council.[44] The tolls collected only marginally covered the cost of collection, leaving no money for conservation, and the bridge had not been cleaned or painted for many years.[43] In 1956 the County Council made a proposal to demolish the bridge and replace it with a new one, but this plan did not come to fruition.[7]

Restoration

After negotiations to raise the required funds, a programme of repairs took place on the foundations of the bridge at a cost of £147,000 between 1972 and 1975.[45] The consulting engineers Sandford, Fawcett, Wilton and Bell elected to place a ferro-concrete inverted arch under the river to counter inward movement of the bridge abutments.[21][46] Construction of the arch was carried out by the Tarmac Construction Company starting in the spring of 1973, but unusually high summer floods washed over the cofferdam, frustrating hopes that the work could be done in a single summer.[47] Filling material was removed from the south abutment to reduce its weight, and the arch through it was reinforced with concrete.[48] The road surface was replaced with a lighter tarmac, the stone of the abutments was renewed and the toll-house was restored as an information centre.[49] In 1980, the structure was painted for the first time in the 20th century, and the work was complete for the bicentenary of the opening, which was celebrated with a pig roast on 1 January 1981.[50]

In 1999–2000, the bridge was scaffolded to allow examination by English Heritage. The bridge was also repainted and minor repairs were carried out.[51] In January 2017 English Heritage announced a £1.2 million restoration project on the Iron Bridge, starting in September 2017, the "biggest ever conservation project" undertaken by English Heritage.[52] The cost was quoted in 2018 at £3.6 million, with English Heritage describing it as "an ambitious conservation of its ribs and arches, its stonework and decking."[53]

Artistic depictions

Over fifty painters and engravers came to the area around Coalbrookdale between 1750 and 1830 to witness and record the rise of industry.[20] Possibly the first artist to depict the bridge was William Williams, who was paid 10 guineas (equivalent to £1,227 in 2016) in October 1780 by Darby for a "drawing" of the bridge.[54] An engraving by Michael Angelo Rooker proved popular, and a copy was purchased by Thomas Jefferson.[55]

In 1979, the Royal Academy of Arts held an exhibition entitled "A View from the Iron Bridge" to commemorate the bicentenary of the bridge.[56]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Harries may have been related to the local Reverend Harries.[14]

- ↑ For a fuller description of the background of the construction of the bridge, see Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 9–18.

References

Citations

- 1 2 "Iron Bridge". Engineering Timelines. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ "Ironbridge Gorge". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ "The Iron Bridge". South Telford Heritage Trail. Stirchley and Brookside Parish Council. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 3

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 3–4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "History and Research: Iron Bridge". English Heritage. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- 1 2 "John Wilkinson and the Iron Bridge". Broseley Local History Society. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Charlton 2002, p. 11

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 9

- 1 2 "Thomas Farnolls Pritchard". ironbridge.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 10–11

- 1 2 Cossons & Trinder (2002), p. 19.

- 1 2 Cossons & Trinder (2002), p. 23.

- ↑ "Why build an Iron Bridge in Coalbrookdale?". Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- 1 2 Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 15

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 16

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 23

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 17

- 1 2 3 Smith 1979, p. 4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "The Iron Bridge". engineering-timelines.com. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 "The Iron Bridge - How was it Built?". BBC. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ↑ "The Iron Bridge". English Heritage. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ↑ "Solved - The mystery of Ironbridge". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ↑ Briggs 1979, p. 7

- ↑ "Secrets of the past: How Ironbridge was built". sean.co.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ↑ Historic England. "Gazebo in garden of number 5 (not included) (1219113)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Tilly 2002, p. 167

- ↑ Tylecote, R. F. (1992). A History of Metallurgy, Second Edition. London: Maney Publishing, for the Institute of Materials. p. 122. ISBN 978-0901462886.

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 29

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 30

- 1 2 3 Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 31–33

- 1 2 3 Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 47

- ↑ "Landslides in the Ironbridge Gorge, Shropshire". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ↑ Petroski 1996, p. 161

- 1 2 Lay 1992, p. 272

- ↑ Powell 2013, p. 57

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 48

- ↑ Hutton 1812, p. 146

- 1 2 Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 50

- ↑ "A Watching Brief at the Free Bridge, Jackfield, Shropshire" (PDF). shropshirehistory.org.uk. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 50–51

- 1 2 3 Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 51

- ↑ Briggs 1979, pp. 50–51

- ↑ "Ironbridge Gorge gets £12m government grant". BBC News. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 52

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 53–54

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 54

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 54–55

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, p. 55

- ↑ "Work on Shropshire's Iron Bridge to start soon". www.ShropshireStar.com. 3 January 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ↑ Bloomfield, Paul (March 2018). "Attention span". English Heritage Members' Magazine. p. 25.

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Cossons & Trinder 2002, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Smith 1979

Sources

- Briggs, Asa (1979). Iron Bridge to Crystal Palace: Impact and Images of the Industrial Revolution. Thames and Hudson in collaboration with the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. ISBN 978-0-500-01222-2.

- Charlton, T. M. (2002). A History of the Theory of Structures in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52482-7.

- Cossons, Neil; Trinder, Barrie Stuart (2002) [1979]. The Iron Bridge: symbol of the Industrial Revolution. Phillimore. ISBN 978-1-86077-230-6.

- Hutton, Charles (1812). Tracts on Mathematical and Philosophical Subjects, Comprising Among Numerous Important Articles, the Theory of Bridges, With Several Plans of Recent Improvement. 1.

- Lay, M. G. (1992). Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles That Used Them. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2691-1.

- Petroski, Henry (1996). Invention by Design: How Engineers Get from Thought to Thing. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-46368-4.

- Powell, John (2013). Ironbridge Gorge Through Time. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-2896-7.

- Smith, Stuart (1979). A View from the Iron Bridge. Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. ISBN 0-903971-09-7.

- Tilly, Graham (2002). Conservation of Bridges. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-419-25910-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Iron Bridge. |

- Iron Bridge & Tollhouse – Ironbridge Gorge Museums Trust

- Virtual tour, from the BBC (VRML plugin required, then use PgUp/PgDn to move between viewpoints)

- River Severn Bridges

- A geological assessment of the landslides in the Ironbridge Gorge, Shropshire (Report)

- The Iron Bridge at Structurae