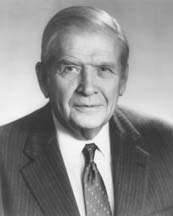

Terry Sanford

| Terry Sanford | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from North Carolina | |

|

In office November 5, 1986 – January 3, 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Jim Broyhill |

| Succeeded by | Lauch Faircloth |

| President of Duke University | |

|

In office 1969–1985 | |

| Preceded by | Douglas Maitland Knight |

| Succeeded by | H. Keith H. Brodie |

| 65th Governor of North Carolina | |

|

In office January 5, 1961 – January 8, 1965 | |

| Lieutenant | Harvey Cloyd Philpott (1961) |

| Preceded by | Luther H. Hodges |

| Succeeded by | Dan K. Moore |

| Chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Ethics | |

|

In office January 3, 1992 – January 3, 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Howell Heflin |

| Succeeded by | Richard Bryan |

| Member of the North Carolina Senate from the 10th district | |

|

In office 1953–1955 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Terry Sanford August 20, 1917 Laurinburg, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died |

April 18, 1998 (aged 80) Durham, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Resting place |

Duke Chapel Durham, North Carolina |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Rose Knight |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

North Carolina Army National Guard |

| Years of service | 1942-1960 |

| Unit | 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

James Terry Sanford (August 20, 1917 – April 18, 1998) was an American university administrator and politician from North Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, Sanford was the 65th Governor of North Carolina (1961–1965), a two-time U.S. Presidential candidate in the 1970s and a U.S. Senator (1986–1993). Sanford was a strong proponent of public education and introduced a number of reforms and new programs in North Carolina's schools and institutions of higher education as the state's governor, increasing funding for education and establishing the North Carolina Fund. From 1969 to 1985, Sanford was President of Duke University.

An Eagle Scout as a youth, Sanford became an FBI agent after graduating from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1939. During World War II, he saw combat in the European Theatre and received a battlefield commission. Following his return to civilian life after World War II, Sanford attended and graduated from the University of North Carolina School of Law and began a legal career in the late 1940s, soon becoming involved in politics. A lifelong Democrat, he was noted for his progressive leadership in civil rights and education; although his opponents criticized him as a "tax-and-spend" liberal, Sanford is remembered as a major public figure of the South after World War II.[1][2]

Early life

Sanford was born in 1917 in Laurinburg, North Carolina, the son of Elizabeth Terry (Martin) and Cecil Leroy Sanford,[3] both of English descent. He became an Eagle Scout in Laurinburg's Troop 20 of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). Shortly before he died, Sanford related his Scouting experience to journalist David Gergen and said that it "probably saved my life in the war. Boys who had been Scouts or had been in the CCC knew how to look after themselves in the woods.... What I learned in Scouts sustained me all my life; it helped me make decisions about what was best."[4] The BSA recognized him with its Distinguished Eagle Scout Award.[5]

Sanford graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1939 and then served as a special agent in the FBI for two years.[6][7] He married Margaret Rose Knight on July 4, 1942, and they later had two children: Terry Jr. and Elizabeth.[8] During World War II, he enlisted as a private in the US Army and later attained the rank of first lieutenant. He parachuted into France with the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment and subsequently fought in the Battle of the Bulge. He was awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart for his bravery and wounds, respectively. Sanford was honorably discharged in 1946.[7]

Sanford later served as a company commander with the rank of captain in Company K of 119th Infantry Regiment of the North Carolina Army National Guard from 1948 to 1960.[9] After the war, Sanford earned a law degree from the University of North Carolina School of Law and served as president of the Young Democratic Clubs of North Carolina, now known as the Young Democrats of North Carolina.

Gubernatorial career

Sanford was an assistant director of the Institute of Government of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1946 until 1948, then began a private practice of law in Fayetteville. Sanford served one term as a state senator (1953–55), and chose not to run for a second term. He ran for governor of North Carolina in 1960, defeating I. Beverly Lake, Sr., Malcolm Buie Seawell, and John D. Larkins in the Democratic primary and Robert Gavin in the general election. Elected to a single term (as North Carolina governors could then be elected for only one term), Sanford served from January 1961 to January 1965.[10]

Education

.jpg)

Driven by his belief that a person could accomplish anything with a good education,[11][12] Sanford nearly doubled North Carolina's expenditures on public schools. He began consolidating the University of North Carolina system to ensure its solvency and strength and oversaw the creation of the North Carolina Community College System. He conceived the idea for the Governor's School of North Carolina,[12] a publicly funded six-week residential summer program for gifted high school students in the state.[13] He established the North Carolina School of the Arts (now University of North Carolina School of the Arts) to keep talented students "in the fields of music, drama, the dance and allied performing arts, at both the high school and college levels of instruction" in their home state.[14]

Controversial tax increases were made to finance the educational programs. One such tax, on food, roused much opposition and was decried as regressive by many, even some of the governor's most loyal supporters. The food tax, nicknamed "Terry's Tax," and other taxes implemented by Sanford diminished his popularity and were heavily criticized by his political opponents.[12]

Race relations and civil rights

Sanford fought for racial desegregation, and he even sent his son to a desegregated public school when such a position was very unpopular. He also established the North Carolina Fund under the leadership of George Esser to fight poverty and promote racial equality across the state.[15]

In January 1964 James Farmer and Floyd McKissick of the Congress of Racial Equality demanded that the city of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, already one of the most integrated communities in the state, fully desegregate by February 1 or face a wave of demonstrations. Sanford released a statement of reproach towards the ultimatum and promised municipal officials his support. He later said, "I felt that I had been pushed around long enough."[16]

Handling the Klu Klux Klan

Meanwhile, activities of the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina rapidly increased. Sanford requested information on the Klan from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). When the reports were found to be insufficient and unsatisfactory, he arranged for an undercover agent of the FBI working in the North Carolina Division of Motor Vehicles to infiltrate the organization in the eastern portion of the state. Several months later the FBI announced that North Carolina had one of the largest Klan membership in the country.[17]

In June 1964 an interracial group of students traveled to Elm City to renovate a local African-American church. Members of the United Klans of America confronted the youths, who promptly left the state. When a larger interracial group arrived to complete the work, 250 klansmen marched into the town and two of them attempted to burn the church down. Sanford publicly condemned the Klan's methods and ordered the State Highway Patrol to assist the municipal police. His staff quietly brokered a compromise, convincing the local pastor to accommodate the white volunteers in a hotel instead of local black residents' homes and avoiding the racial mixing of which the klansmen disapproved. State authorities dealt with members of the Klan in a similarly accommodating manner throughout the rest of Sanford's tenure, allowing the organization to strengthen its position in the region.[18] In response to Sanford's criticism of their actions in Elm City, klansmen burnt a cross on the lawn of the Governor's Mansion in mid-August.[19] Sanford inspected the cross, later commenting, "It is a badge of honor to have such hoodlums against you, but it is a mark of shame for the state of North Carolina to have such childish activities going on."[20]

Relationship with John F. Kennedy

Sanford was a close political ally of President John F. Kennedy, a fact that disturbed some North Carolina Democrats suspicious of Kennedy's Catholicism.[21] According to Kennedy's personal secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, Sanford would have been Kennedy's choice for vice president on the 1964 Democratic ticket if Kennedy had lived. In her 1968 book Kennedy and Johnson she reported that Kennedy, told her that Lyndon B. Johnson would be replaced as Vice President.

Lincoln wrote of that November 19, 1963, conversation just three days before Kennedy's assassination:[6][22]

As Mr. Kennedy sat in the rocker in my office, his head resting on its back he placed his left leg across his right knee. He rocked slightly as he talked. In a slow pensive voice he said to me, 'You know if I am re-elected in sixty-four, I am going to spend more and more time toward making government service an honorable career. I would like to tailor the executive and legislative branches of government so that they can keep up with the tremendous strides and progress being made in other fields ... I am going to advocate changing some of the outmoded rules and regulations in the Congress, such as the seniority rule. To do this I will need as a running mate in sixty-four a man who believes as I do.' ... I was fascinated by this conversation and wrote it down verbatim in my diary. Now I asked, ... 'Who is your choice as a running-mate?' He looked straight ahead, and without hesitating he replied, 'At this time I am thinking about Governor Terry Sanford of North Carolina. But it will not be Lyndon.'

Additionally, Sanford used his leverage with the White House to expand the Research Triangle Park (RTP), which sparked an economic surge in the state, eventually luring IBM and the United States Environmental Protection Agency to the Triangle area.[21][23][24]

Other positions

Sanford was also a staunch opponent of capital punishment. His "numerous statements against capital punishment were so well known that prisoners on North Carolina’s death row pointedly referred to them in their clemency appeals."[25]

Return to private career

After his term in office ended, Sanford opened a law firm. He had agreed to serve as Johnson's campaign manager in 1968 just before Johnson's withdrawal on March 31. Sanford later took over as the campaign manager for the Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey in his race against Republican Richard Nixon for the presidency.[8]

Johnson wanted Humphrey to pick Sanford as his running mate. On one occasion, the Humphrey campaign asked Sanford if he wanted to be the vice presidential candidate. Sanford declined, and Humphrey ultimately picked Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine. Though Sanford received a number of legal and business offers from the private sector during this period, he was interested in a position that would allow him to keep his political prospects open.[26]

President of Duke University

In 1969, Sanford became president of Duke University, a position he held for the next 16 years.[27] That helped quell student unrest over the Vietnam War early in his tenure as university president. Addressing the protests of the 1970 Kent State shootings with tolerance, choosing to not call in police to clear the roads, leading to the protesting students going back to their rooms at night so that West Campus could be reopened the next day kept the campus calm during a turbulent spring.[28] Shortly before his tenure, on February 13, 1969, 60 student members of the Afro-American Society had occupied Duke's main administration center, the Allen Building, demanding the creation of a Black Studies program. After three days of clashes with police, they left the building peaceably February 16, when school officials agreed to the program.[29][30] During his tenure, Sanford strongly opposed confrontation and a heavy police action which helped defuse racial tensions.[31]

Perhaps the greatest controversy of Sanford's presidency was his effort to establish the presidential library of former US President Richard Nixon at Duke. Sanford raised the subject with Nixon during a visit to the former president at Nixon's New York City office on July 28, 1981. Sanford continued to seek Nixon's advice on multiple issues within the months that followed. The library proposal became public in mid-August, creating considerable controversy at the university. Though Sanford enjoyed some support for his effort, most of the faculty were against the proposal, the largest concern being that the facility would be a monument to Nixon rather than a center of study. Sanford tried to engineer a compromise, but the proposal by the Duke Academic Council of a library only a third the size of that which Nixon wanted and their rejection of a Nixon museum to accompany it, ultimately led Nixon to decline Sanford's offer and site his library in the city of his birth, Yorba Linda, California, instead; it was dedicated there in 1990.[32]

Campaigns for the Democratic presidential nomination

Though Sanford enjoyed his time as Duke's president, he still harbored political ambitions. As the 1972 presidential primary season began, he was approached by several people who felt that the field of Democratic candidates was weak. He was particularly keen to challenge Alabama governor George Wallace in an effort to show that Wallace's segregationist views did not represent majority Southern opinion. Announcing his candidacy on March 8, he faced long odds in a crowded field. Knowing that he could not win a majority of delegates in the primary, he hoped to secure enough to emerge as a compromise candidate in a deadlocked convention. Even in the North Carolina primary, however, Wallace beat Sanford by 100,000 votes, and Sanford managed only a fifth-place finish at the 1972 Democratic National Convention with 77.5 votes, behind George McGovern (1,864.95), Henry M. Jackson (525), Wallace (381.7), and Shirley Chisholm (151.95).[33][34]

Undeterred, Sanford began preparations two years later for a run for the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination.[35] Announcing his candidacy on June 1, 1975, he juggled campaign appearances with his obligations as president of Duke. While he developed a following among educators, he did not have a satisfactory campaign theme by the new year. Then, while campaigning in Massachusetts in January, he suffered sharp pains and was diagnosed with a heart murmur. On January 25, Sanford withdrew from the primaries, the first Democrat to do so that year.[36]

Senate career

After retiring as president of Duke University in 1985, Sanford remained active in party politics. He made an unsuccessful run for chairman of the Democratic National Committee in 1985, in which he was supported by future House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Sanford lost to Paul G. Kirk by a vote of 203–150.[37]

After failing to find a Democrat willing to run for the Senate seat being vacated by Republican John P. East,[38] Sanford announced his own candidacy for the nomination. His opponent was Congressman Jim Broyhill. After East committed suicide on June 29, 1986, Broyhill was temporarily appointed to the seat on July 3, until a special election could be held on November 4.[39] Despite being attacked as a liberal, Sanford defeated Broyhill by three percentage points in the November election. Critics of Sanford primarily focused on three areas: his promotion of opportunities for minorities, "tax-and-spend" education funding, and his anti-poverty campaign.[6] He took office on November 5, the day after the special election, to serve out the last two months of East's term and the subsequent six-year term.[10]

Sanford found his years in the Senate frustrating. He was concerned about the runaway deficit spending of the era, and he pursued economic development for Central America as an alternative to Republican-driven military policies. He led the Duke-based International Commission for Central American Recovery and Development, a task force of scholars and leaders that published Poverty, Conflict, and Hope: A Turning Point in Central America (also known as the Sanford Commission Report since he was "the principal catalyst of the commission's work") in 1989 with the principles for promoting peace, democracy and equitable development in Central America.[40] Sanford served on multiple Senate committees: Select Committee on Ethics (Chair); Special Committee on Aging; Budget; Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs including the Subcommittee on International Finance and Monetary Policy and Subcommittee on Securities; and Foreign Relations including Subcommittee on Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs (Chair), Subcommittee on African Affairs, and Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere and Peace Corps Affairs.[41] He had a liberal voting record in comparison to his Democratic colleagues from the South, and he campaigned successfully against the passage of a constitutional amendment prohibiting flag-burning with a counter-campaign promoting the United States Bill of Rights. Yet Sanford thought his accomplishments in the Senate paled against those he made as governor, and he seriously contemplated retiring and pursuing other projects before deciding to run for reelection.[42] His voting record was consistently more liberal than that of any of his predecessors, being given an American Conservative Union rating of 12%.[43]

Sanford's opponent in the 1992 election was Lauch Faircloth, a former Democrat turned Republican who had served as state Highway Commissioner in Sanford's gubernatorial administration. Enjoying substantial backing from Sanford's Senate colleague, Jesse Helms, Faircloth accused Sanford of being a tax-and-spend liberal bound to special interests. While initial polls showed that Sanford had a comfortable lead over his rival, he lost supporters after an operation for an infected heart valve kept him from campaigning for much of October and raised doubts as to whether he was capable of serving another term. On November 3, 1992, Faircloth won the election by a 100,000-vote margin.[44]

Later life

Sanford wrote several books, including: But What About the People?, where he describes his efforts during the 1960s to establish a system of quality public education in North Carolina; Storm Over the States, where he lays forth a new groundwork for state government and the federal system by recommending a "creative federalism"; and Outlive Your Enemies: Grow Old Gracefully, where he describes actions that will slow the aging process and rules for prolonging healthy life.[45] He also taught classes in law and political science at Duke University and campaigned for the construction of a major performing arts center in the Research Triangle area that would provide a permanent home for the American Dance Festival, the North Carolina Symphony and the Carolina Ballet.[46] Sanford practiced law again in his later years and merged his own firm with that of another former governor, James Holshouser. Holshouser continued to practice with Sanford Holshouser LLP until his death (the firm continues under that name), and their economic development consulting firm continued under that name.[47]

The New York Times writer David Stout characterized Sanford as a "contradictory politician" and a man who "lack[ed] burning desire."[48]

Sanford announced in late December 1997 that he had been diagnosed with inoperable esophageal cancer and that his doctors said he had a few months to live. After his release from the hospital, his condition slowly deteriorated. He died in his sleep while surrounded by his family at his Durham home. He was 80 years old. At his funeral, he was eulogized by a childhood friend who said Sanford "took [the Boy Scout] oath when he was twelve years old and kept it. It started out, 'On my honor, I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country,' and included such things as 'help other people at all times.' He believed it. He was the eternal Boy Scout."[4] Sanford is entombed in the crypt of Duke University Chapel.[8]

Legacy

"Sanford was a very engaging extrovert....His vision in life was to help people. He had a huge ego. Of all the people I've known in politics, he had the strongest focus on government being there to make life better for the people. He was very optimistic."

Sanford was a major public figure of the post-World War II South.[1][2] He played a key role in the transformation of Southern politics into the New South, primarily in the areas of race relations and education.[50][51] In recognition of his efforts in education and in countless other areas, a 1981 Harvard University survey named him one of the 10 best governors of the 20th century.[8][52]

The Terry Sanford Federal Building and Courthouse in Raleigh, the state capital, is named after Sanford.[53] President Bill Clinton said in a statement issued from the Summit of the Americas in Santiago, Chile: "His work and his influence literally changed the face and future of the South, making him one of the most influential Americans of the last 50 years."[2] John Edwards said in Terry Sanford and the New South that Sanford was his political hero.[51]

Duke University has since established an undergraduate and graduate school (formerly institute) in public policy called the Sanford School of Public Policy.[54] Fayetteville High School, in Fayetteville, North Carolina, was renamed Terry Sanford High School in his honor in 1968.[55][56]

See also

Citations

- 1 2 Clinton, Bill (1998-04-18). "Presidential Statement on the Death of Terry Sanford". William J. Clinton Foundation. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- 1 2 3 "Southern Connections: Connecting With Each Other, Connecting With The Future:Terry Sanford" (PDF). The Summary Report of the 1998 Commission on the Future of the South. Southern Connections. 1998. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-27. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ http://www.carolana.com/NC/Governors/tsanford.html

- 1 2 Townley 2007, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ "Distinguished Eagle Scouts" (PDF). Scouting.org. Retrieved 2010-11-04.

- 1 2 3 Stout, David (1998-04-18). "Terry Sanford, Pace-Setting Governor in 60's, Dies at 80". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- 1 2 "Biographical Conversations with Terry Sanford - Timeline". UNC TV. Archived from the original on 2002-01-02. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Christensen, Rob (April 18, 1998). "Terry Sanford dead at 80, April 19, 1998". Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, Duke University. Raleigh News & Observer. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, p. 99.

- 1 2 "Sanford, (James) Terry, (1917–1998)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 157, 194, 247, 257–258.

- 1 2 3 "State of Learning". Time Magazine. 1964-01-24. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ "Governor's School of North Carolina". Governor's School of North Carolina. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ "Semans Library: UNCSA History". University of North Carolina School of the Arts. Archived from the original on 2011-12-07. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ↑ "July 1963 – The North Carolina Fund". This Month in North Carolina History. UNC University Libraries. July 1963. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis, pp. 341–342.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis, p. 342.

- ↑ Cunningham 2013, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Cunningham 2013, p. 57.

- ↑ "Cross Is Burned On Governor's Mansion Lawn". The Robesonian. XCV (130). Raleigh: Associated Press. August 14, 1964. p. 1.

- 1 2 Christensen, Rob (2004). "Old ties bind N.C. to Mass". Raleigh News & Observer. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ↑ Lincoln 1968, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Bass & De Vries 1976, p. 230.

- ↑ McConville, Elizabeth (2005-12-02). "What was behind the main idea of behind "research triangle park"" (doc). Elon College. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Gottschalk, Marie (2011-03-16) Is Death Different?, The New Republic

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 367–385.

- ↑ "Inventory of the Terry Sanford Papers, 1946–1993". Collection Number 3531. Manuscript Department, University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, p. 259.

- ↑ 1970 Reader's Digest Almanac and Yearbook p. 12.

- ↑ Struggling for Its Place — Duke's Black Studies Program Appeals to President Terry Sanford Archived 2013-12-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chambers Jr., Stanley B. (2006-10-14). "Unity concept nothing new to Duke, N.C. Central". The News & Observer. Raleigh. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 369–396, 417–432.

- ↑ "Introducing... the McGovern Machine". Time Magazine. 1972-07-24. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ↑ Holland, Keating (1996). "All The Votes ... Really". CNN.com. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 396–400.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 396–416.

- ↑ Shogan, Robert (February 2, 1985). "Democrats Elect Paul Kirk Chairman in Bitter Contest". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ↑ "East, John Porter, (1931 - 1986)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ "Broyhill, James Thomas, (1927 –)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Zuvekas, Clarence, Jr. (1992). "Alternative Perspectives on Central American Economic Recovery and Development". Latin American Research Review. Pittsburgh, PA: The Latin American Studies Association. 27 (1): 125–150 [128]. ISSN 0023-8791. JSTOR 2503721.

- ↑ "Guide to the Terry Sanford Papers, 1926–1996". Duke University Libraries. 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 447–480.

- ↑ Cooper & Knotts 2012, p. 73.

- ↑ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 488–501.

- ↑ "A Joint Resolution Honoring The Life And Memory Of Terry Sanford, One Of North Carolina's Most Distinguished Citizens". General Assembly of North Carolina. 1999-03-23. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ "Terry Sanford: August 20, 1917 – April 18, 1998". Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy. Duke University. Archived from the original on December 14, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ↑ Sanford Holshouser Economic Development

- ↑ Stout, David (19 April 1998). "Terry Sanford, Pace-Setting Governor in 60's, Dies at 80". New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ↑ Eamon 2014, p. 78.

- ↑ Bass, Jack; DeVries, Walter (2004). "Oral History Interview with Terry Sanford". Southern Oral History Program. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill – Documenting the American South. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- 1 2 "Terry Sanford and the New South". Duke University News. 2007-04-03. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Adams, Kathleen; Buechner, M.M.; Eisenberg, Daniel; Gray, Tam; Hamilton, Anita; Kaplan, Glenn; Morse, Jodie; Orecklin, Michele; et al. (1998-04-27). "Milestones". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ "North Carolina Federal Building". United States General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2009-06-17. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ↑ "Terry Sanford School of Public Policy". Duke University. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ "Terry Sanford High School, Fayetteville, NC". Terry Sanford High School. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ "The History of Fayetteville Senior High School". Fayetteville High School Classmates. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

References

- Bass, Jack; De Vries, Walter (1995). The Transformation of Southern Politics:Social Change and Political Consequence Since 1945 (reprint ed.). Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. p. 230. ISBN 0-452-00470-5.

- Cooper, Christopher A.; Knotts, H. Gibbs, eds. (2012). The New Politics of North Carolina. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469606583.

- Covington, Howard E., Jr; Ellis, Marion A. (1999). Terry Sanford: Politics, Progress, and Outrageous Ambitions. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822323563.

- Cunningham, David (2013). Klansville, U.S.A: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-era Ku Klux Klan (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 9780199752027.

- Eamon, Tom (2014). The Making of a Southern Democracy: North Carolina Politics from Kerr Scott to Pat McCrory. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469606972.

- Lincoln, Evelyn (1968). Kennedy and Johnson (1st ed.). Austin, TX: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Townley, Alvin (2007) [2006]. Legacy of Honor: The Values and Influence of America's Eagle Scouts. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-36653-1.

Further reading

- Drescher, John (2000). Triumph of Good Will: How Terry Sanford Beat a Champion of Segregation in and Reshaped the South. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-310-8.

- Korstad, Robert R.; Leloudis, James L. (2010). To Right These Wrongs: The North Carolina Fund and the Battle to End Poverty and Inequality in 1960s America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-7114-0.

- Leloudis, James L.; Korstad, Robert R. (2003). "Citizen Soldiers; The North Carolina Volunteers and the South's War on Poverty". In Elna C. Green. The New Deal and Beyond: Social Welfare in the South since 1930. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. pp. 138–162.

Selected books by Terry Sanford

- Sanford, Terry (1966). But What about the People?. New York, NY: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-8223-2356-7.

- Sanford, Terry (1967). Storm over the States. Rochester, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-054655-X.

- Sanford, Terry (1981). A Danger of Democracy: The Presidential Nominating Process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-86531-159-5.

- Sanford, Terry (1996). Outlive Your Enemies: Grow Old Gracefully. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 1-56072-289-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terry Sanford. |

- To Right These Wrongs: The North Carolina Fund and the Battle to End Poverty and Inequality in 1960s America

- Civil Rights Greensboro: Terry Sanford

- Guide to the Terry Sanford Papers, 1926–1996, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.

- Terry Sanford for President 1976 Campaign Brochure

- Oral History Interviews with Terry Sanford , , , , from Oral Histories of the American South

- Appearances on C-SPAN

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Luther H. Hodges |

Governor of North Carolina January 5, 1961- January 8, 1965 |

Succeeded by Dan K. Moore |

| Preceded by Howell Heflin |

Chairman of the Senate Ethics Committee 1992–1993 |

Succeeded by Richard Bryan |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by James Thomas Broyhill |

Senator from North Carolina (Class 3) November 5, 1986–January 3, 1993 Served alongside: Jesse Helms |

Succeeded by Lauch Faircloth |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Douglas Maitland Knight |

President of Duke University 1969–1985 |

Succeeded by H. Keith H. Brodie |