Frank Porter Graham

| Frank Porter Graham | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from North Carolina | |

|

In office March 29, 1949 – November 26, 1950 | |

| Appointed by | W. Kerr Scott |

| Preceded by | Joseph Melville Broughton |

| Succeeded by | Willis Smith |

| President of the University of North Carolina | |

|

In office 1930–1949 | |

| Preceded by | Harry Woodburn Chase |

| Succeeded by | Gordon Gray |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

October 14, 1886 Fayetteville, North Carolina |

| Died |

February 16, 1972 (aged 85) Chapel Hill, North Carolina |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Marian Drane Graham |

| Relations | Archibald Wright "Moonlight" Graham |

| Alma mater |

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Columbia University |

| Profession | Educator, diplomat, politician |

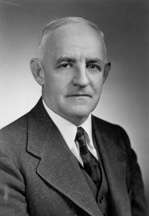

Frank Porter Graham (October 14, 1886 – February 16, 1972) was an American educator and political activist. A professor of history, he was elected President of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1930, and he later became the first President of the consolidated University of North Carolina system.

Graham was an active champion of many liberal causes including academic freedom, economic justice, civil rights, disarmament and world peace. He served on numerous advisory boards for Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, and in 1949 he was appointed by the North Carolina governor to fill a vacant seat in the United States Senate. His effort to win election in the following year turned into a bitter and ultimately unsuccessful struggle with conservative Democrat Willis Smith.

In 1951 he was appointed as a United Nations mediator for the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. He pursued that elusive goal for 16 years, and he continued his advocacy work on many other issues, until failing health forced him to retire from public life in 1967.

Early life

Frank Porter Graham was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina in 1886, the sixth of nine children born to Alexander and Katherine Bryan Sloan Graham.[1][2] His father was superintendent of the Charlotte school system for 25 years,[2] and many of his siblings and other family relations were teachers.[3] His older brother, Archibald Wright "Moonlight" Graham (December 28, 1879 – August 25, 1965), was a professional baseball player with the New York Giants (and inspiration for the 1989 film Field of Dreams).

Graham attended the original University of North Carolina (UNC, now called University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), from which he was graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors in 1909.[2] He was an active and popular student, serving as the editor of the college newspaper and the yearbook, president of the debating society, president of the campus YMCA, Senior class president, and the university's head cheerleader.[4] He thereafter studied law and received his license in 1913. He received a graduate degree in 1916 from Columbia University. While he was studying law, Graham worked as a high school teacher in Raleigh, North Carolina. He went on to serve as a history instructor at UNC beginning in 1915. He interrupted his teaching career to enlist in 1917 in the United States Marine Corps for service in World War I. Enlisted as a private, he was discharged as a first lieutenant in 1919.[2][5]

Graham returned to the History department at UNC and was promoted to a professorship in 1927, despite not having earned a Ph.D. He also served briefly as Dean of Students.[2]

President of the University of North Carolina

In June 1930, Graham was elected President of UNC, succeeding Harry Woodburn Chase.[6] Two years later, he married Marian Drane of Baltimore, Maryland. Their wedding ceremony was performed by the bride's father, who was the rector of Baltimore's historic St. Paul's Episcopal Church for more than 50 years.[7]

Just months after his marriage, in November 1932, Graham was chosen to lead the consolidation of the University of North Carolina system, which brought together the three public colleges in the state: Graham's UNC at Chapel Hill, the North Carolina College for Women (now the University of North Carolina at Greensboro), and State College (now North Carolina State University).[2][8] He served as President of the university system for the next 17 years.[2]

In 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Graham as chairman of his Advisory Council on Economic Security, which made proposals that led to the Social Security Act the following year.[9] In 1938, Graham headed the Advisory Committee on Economic Conditions in the South which issued a report detailing the dire position of the region.[10] Immediately afterward, Graham helped establish the Southern Conference on Human Welfare (SCHW), an advocacy group that organized poverty relief efforts and promoted New Deal policies.[10]

After Roosevelt's death, new President Harry Truman continued to utilize Graham, and appointed him to the President's Committee on Civil Rights in 1946. But in the following year, Graham was mentioned in hearings held by the House Committee Investigating Un-American Activities for his involvement with the SCHW, which was alleged to be a Communist front organization.[11] Graham denied any Communist affiliation, but was tarnished by accusations of "pinkish" sympathies for years.[12]

During this time, Graham became involved with United Nations diplomatic work. Appointed to the UN commission arbitrating peace in the Indonesian National Revolution, Graham helped open direct negotiations between Indonesian and Dutch representatives at Batavia aboard USS Renville in December 1947.[13]

United States Senator

In 1948, former state agriculture commissioner W. Kerr Scott was elected Governor of North Carolina. Like Graham, Scott was a pro-Truman Democrat who had supported the New Deal. Two months after Scott's inauguration, incumbent U.S. Senator J. Melville Broughton died in office. Broughton's death provided Scott with a prime opportunity to make a mark in Washington, D.C. After three weeks of intense speculation throughout March 1949 as to whom the governor might choose for the Senate, attention focused on individuals ranging from the senator's widow, who expressed no interest; Scott's former campaign manager, Capus Miller Waynick; another Scott supporter, Major Lennox Polk McLendon, a lawyer from Greensboro, North Carolina; former Senator Umstead; and the governor himself. Scott appointed Graham, which shocked many in the state.[14]

At the time of his appointment, Graham had never sought nor served in any political office, an unusual phenomenon at the time for North Carolina senators.[14] Also atypical was that the particular Senate seat Graham occupied was in a period of considerable turnover. Beginning with the death of Senator Josiah W. Bailey in 1946, and concluding with the election of B. Everett Jordan in 1958, no fewer than eight men served in the seat in a dozen years.

1950 Democratic primary

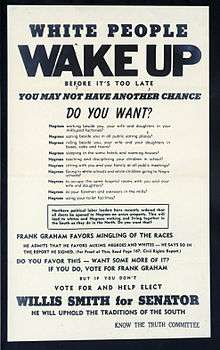

Graham faced two opponents in the 1950 Democratic primary, including former Senator Robert R. Reynolds and former Speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives Willis Smith. Reynolds was eliminated with only 10% of the vote, while Smith and Graham received 41% and 49% respectively. Graham was one percentage point below the threshold of receiving the nomination outright, and Smith could have chosen to engage Graham in a runoff. Smith initially declined, but when his supporters rallied outside his house in a show of support, Smith changed his mind.[14]

In the runoff, Smith ran as an anti-Truman Democrat. According to his staffers, Smith never said anything outright racist, but some of his supporters released unofficial pamphlets stirring up fears of an integrated society.[14] The campaign is considered by historians as the most racist for a senate race in North Carolina since the beginning of popular vote for senators.[15]

At the time of the election, few African-Americans were voting in North Carolina because of Jim Crow laws designed to disenfranchise them. Those blacks who were registered usually were Republicans who cast ballots only in routine general elections. Graham was hence unable to appeal to many black voters, and he did not call for immediate integration, either.[14] Graham was not a natural campaigner and hesitated to even ask voters for their vote.[14] His political views were different from most North Carolinians'.[14]

In the virtually all-white Democratic primaries, the tactics of Smith's campaign supporters (among whom was future Republican Senator Jesse Helms) worked along with these other factors,[14] and Smith prevailed by a narrow 52%-48%.

Graham's supporters mounted a write-in candidacy for the November general election, but he received only one-half of one percent, and Smith won in a landslide against a desultory GOP opponent.

Post-Senate

After his short Senate stint, Graham entered the field of world politics and diplomacy. He served as a mediator at the United Nations as a representative to India and Pakistan in the Kashmir dispute, serving in this capacity from 1951 through 1967.[16] He retired from U.N. service in 1967 at the age of 81 and returned to Chapel Hill, after his wife died.[14]

Graham died in Chapel Hill at the age of 85. He is interred at the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery.[5] Some nine months after Graham's death, his old Senate seat went to a former aide to the late Willis Smith, Jesse Helms.

UNC-Chapel Hill's student union building is named in Graham's honor, as is the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute (FPG.unc.edu), one of the nation's oldest and largest multidisciplinary centers devoted to the study and care of young children. The Frank Porter Graham Elementary School in Chapel Hill and the Frank Porter Graham Building on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro also honor the former senator.

Graham, along with Eleanor Roosevelt and Hubert Humphrey and other anticommunist liberals of the era, was affiliated with the liberal advocacy group, the Americans for Democratic Action.

Since 1968, the North Carolina chapter of the ACLU has acknowledged people who work towards the promotion of civil liberties in the state with the Frank Porter Graham Award.[17] Graham's life story was the subject of a 1994 documentary, Dr. Frank: The Life and Times of Frank Porter Graham, narrated by Charles Kuralt.[18]

References

- ↑ Wilson and Clark, 06:50

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sitterson, J. Carlyle (1996) [1979]. Powell, William S., ed. Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. University of North Carolina Press. "Graham, Frank Porter".

- ↑ Wilson and Clark, 07:30

- ↑ Wilson and Clark, 08:40

- 1 2 United States Congress. "Frank Porter Graham (id: G000353)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Frank P. Graham Is Head N.C. University". The Greenville News. Greenville, South Carolina. AP. June 10, 1930. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Head of North Carolina University Takes Bride". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. July 22, 1932. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Dr. Graham To Head Greater N.C. University". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. AP. November 15, 1932. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Wilson and Clark, 26:15

- 1 2 Wilson and Clark, 26:45

- ↑ Wilson and Clark, 34:10

- ↑ Wilson and Clark, 37:10

- ↑ "Java Negotiations Open Amicably" (PDF). The New York Times. AP. December 8, 1947. p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wilson and Clark

- ↑ "The 1950 Senate campaign". LEARN NC. UNC-Chapel Hill School of Education. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ Staff (February 17, 1972). "Dr. Frank Graham Dies at 85; Civil Rights Leader in the South". The New York Times.

- ↑ "2016 Frank Porter Graham Award recipient: Bob Hall". ACLUofNorthCarolina.org. February 18, 2016. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018.

- ↑ "UNC-TV documentary recalls life of Frank Porter Graham". Asheville Citizen-Times. Asheville, North Carolina. November 2, 1994. p. 11. Retrieved September 10, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

- John Wilson and Martin Clark (producers) (1994). Dr. Frank: The Life and Times of Frank Porter Graham. Chapel Hill: UNC-TV.

Further reading

- Pleasants, Julian M.; Augustus M. Burns III (1990). Frank Porter Graham and the 1950 Senate Race in North Carolina. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1933-3.

- Finley, Keith M. Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938-1965 (Baton Rouge, LSU Press, 2008).

External links

- Office of President of the University of North Carolina: Frank Porter Graham Records, 1930–1932, in the University Archives, UNC-Chapel Hill

- Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Frank Porter Graham Records, 1932–1949, in the University Archives, UNC-Chapel Hill

- Frank Porter Graham Papers, 1908–1972, in the Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

| U.S. Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by J. Melville Broughton |

U.S. Senator (Class 2) from North Carolina 1949–1950 Served alongside: Clyde Roark Hoey |

Succeeded by Willis Smith |