Tamambo language

| Tamambo | |

|---|---|

| Malo | |

| Native to | Vanuatu |

| Region | Malo Island, Espiritu Santo |

Native speakers | 4,000 (2001)[1] |

|

Austronesian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

mla Malo[2] |

| Glottolog |

malo1243 Tamambo[3] |

Tamambo,[3] or Malo,[1][2] is an Oceanic language spoken by 4,000 people on Malo and nearby islands in Vanuatu.

Phonology

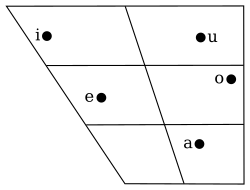

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Low | a |

/i u/ become [j w] respectively when unstressed and before another vowel. /o/ may also become [w] for some speakers.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labiovelarized | |||||

| Nasal | m | mʷ | n | ŋ | ||

| Stop | prenasalized | ᵐb | ᵐbʷ | ⁿd | ᶮɟ | |

| plain | t | k | ||||

| Fricative | voiced | β | βʷ | x | ||

| voiceless | s | |||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Lateral | l | |||||

The prenasalized postalveolar stop /ᶮɟ/ is often affricated and voiceless, i.e. [ᶮtʃ].

Younger speakers often realize /β/ as [f] initially and [v] medially, while /βʷ/ is often replaced by [w].

/x/ is usually realized as [x] initially, but some speakers use [h]. Medially, it may be pronounced as any of [x ɣ h ɦ ɡ].

Writing system

Few speakers of Tamambo are literate, and there is no standard orthography. Spelling conventions used include:

| Phoneme | Representation |

|---|---|

| /ᵐb/ | B initially, mb medially. |

| /ᵐbʷ/ | Bu or bw initially, mbu or mbw medially. |

| /x/ | C or h. |

| /ⁿd/ | D initially, nd medially. |

| /ᶮɟ/ | J initially, nj medially. |

| /k/ | K. |

| /l/ | L. |

| /m/ | M. |

| /mʷ/ | Mu or mw. |

| /n/ | N. |

| /ŋ/ | Ng. |

| /r/ | R. |

| /s/ | S. |

| /t/ | T. |

| /β/ | V. |

| /βʷ/ | Vu or w. |

Pronouns and person markers

In Tamambo, personal pronouns distinguish between first, second, and third person. There is an inclusive and exclusive marking on the first-person plural and gender is not marked. There are four classes of pronouns, which is not uncommon in other Austronesian languages:[5]

- Independent pronouns

- Subject pronouns

- Object pronouns

- Possessive pronouns.

| Independent pronouns | Subject pronouns | Object pronouns | Possessive pronouns | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | iau | ku | -(i)au | -ku |

| 2SG | niho | o | -ho | -m |

| 3SG | nia | mo (realis) / a (irrealis) | -a / -e | -na |

| 1PL.I | hinda | ka | -nda | -nda |

| 1PL.E | kamam | ka | kamam | -mam |

| 2PL | kamim | no | kamim | -mim |

| 3PL | nira | na | -ra | -ra |

Independent pronouns

Independent pronouns behave grammatically similarly to other NPs in that they can occur in the same slot as a subject NP, functioning as the head of a NP. However, in regular discourse, they are not used a great deal due the obligatory nature of cross-referencing subject pronouns. Use of independent pronouns is often seen as unnecessary and unusual except in the following situations:

- Indicate person and number of conjoint NP

- Introduce new referent

- Reintroduce referent

- Emphasise participation of known referent

Indicating person and number of conjoint NP

In the instance where two NPs are joined as a single subject, the independent pronoun reflects the number of the conjoint NP:

Ku vano. 1SG go 'I went.'

and

Nancy mo vano. Nancy 3SG go 'Nancy went.'

Thus, merging the two above clauses into one, the independent pronoun must change to reflect total number of subjects:

Kamam mai Nancy ka vano. IP:1PL.E PREP Nancy 1PL go 'Nancy and I went.'[7]

Introducing a new referent

When a new referent is introduced into the discourse, the independent pronoun is used. In this case, kamam:

Ne kamam mwende talom, kamam ka-le loli na hinau niaro. But IP:1PL.E particular.one first IP:1PL.E 1PL-TA do ART thing EMPH 'But we who came first, [well] as for us, we do this very thing'[8]

Reintroduction of referent

In this example, the IP hinda in the second sentence is used to refer back to tahasi in the first sentence.

Ka tau tahasi mo sahe, le hani. Hani hinda ka-le biri~mbiri. 1PL put.in.place stone 3SG go.up TA burn burn IP:1PL.I 1PL-TA RED~grate 'We put the stones up (on the fire) and it’s burning. While it’s burning we do the grating [of the yams].'[9]

Emphasis on participation of known subject

According to Jauncey,[10] this is the most common use of the IP. Comparing the two examples, the latter placing the emphasis on the subject:

O vano? 2SG go 'Are you going?'

and

Niho o vano? IP:2SG 2SG go 'Are you going?'[11]

Subject pronouns

Subject pronouns are an obligatory component of a verbal phrase, indicating the person and number of the NP. They can either co-occur with the NP or independent in the subject slot, or exist without if the subject has been deleted through ellipsis or previously known context.

Balosuro mo-te sohena. nowadays 3SG-NEG the.same 'It's not like that nowadays.'[12]

Object pronouns

Object pronouns are very similar looking to independent pronouns, appearing to be abbreviations of the independent pronoun as seen in the pronoun paradigm above. Object pronouns behave similarly to the object NP, occurring in the same syntactic slot, however only one or the other is used, both cannot be used simultaneously as an object argument – which is unusual in Oceanic languages as many languages have obligatory object pronominal cross-referencing on the verb agreeing with NP object.

Mo iso ka turu ka vosai-a 3SG finish 1PL stand 1PL cook.in.stones-O:3SG 'Then we bake it in the stones.'[13]

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns substitute for NP possessor, suffixing to the possessed noun in direct possessive constructions or to one the four possessive classifiers in indirect constructions.

Direct possession

Tama-k' mo vora bosinjivo. Father-POSS:1SG 3SG be.born bosinjivo.area 'My father was born in the Bisinjivo area.'[14]

Indirect possession

ma-m ti CLFR-POSS:2SG tea 'your tea'[15]

External links

- Materials on Malo are included in the open access Arthur Capell collections (AC1 and AC2) held by Paradisec.

References

- 1 2 Malo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- 1 2 "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: mla". ISO 639-3 Registration Authority - SIL International. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

Name: Malo

- 1 2 Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Tamambo". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Riehl & Jauncey (2005:256)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:87)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:88)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:89)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:89)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:90)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:90)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:91)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:435)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:430)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:434)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:102)

Bibliography

- Jauncey, Dorothy G. (1997). A Grammar of Tamambo, the Language of Western Malo, Vanuatu. Ph.D. dissertation, Australian National University, Canberra.

- Jauncey, Dorothy G. (2002), "Tamambo", in Lynch, J.; Ross, M.; Crowley, T., The Oceanic Languages, Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, pp. 608&ndash, 625

- Jauncey, Dorothy G. (2011). A Grammar of Tamambo, the Language of Western Malo, Vanuatu. Australian National University, Canberra.

- Riehl, Anastasia K.; Jauncey, Dorothy (2005). "Illustrations of the IPA: Tamambo". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 255–259. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002197.