TRAPPIST-1d

| Exoplanet | List of exoplanets | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Parent star | ||

| Star | TRAPPIST-1[1] | |

| Constellation | Aquarius | |

| Right ascension | (α) | 23h 06m 29.283s |

| Declination | (δ) | –05° 02′ 28.59″ |

| Apparent magnitude | (mV) | 18.8[2] |

| Distance | 39.5 ± 1.3 ly (12.1 ±0.4[2] pc) | |

| Spectral type | M8V[2][3] | |

| Mass | (m) | 0.089 (± 0.006)[1] M☉ |

| Radius | (r) | 0.121 (± 0.003)[1] R☉ |

| Temperature | (T) | 2516 (± 41.0)[1] K |

| Metallicity | [Fe/H] | 0.04 (± 0.08)[4] |

| Age | 3-8[2] Gyr | |

| Physical characteristics | ||

| Mass | (m) | 0.297 +0.035 −0.039[5] M⊕ |

| Radius | (r) | 0.784 +0.023 −0.023[5] R⊕ |

| Stellar flux | (F⊙) | 1.043+0.06 −0.06[6] ⊕ |

| Density | (ρ) | 3.39 +0.34 −0.37 g cm−3 |

| Surface gravity | (g) | 0.483 +0.048 −0.052[5] g |

| Temperature | (T) | 282.1 ± 4.0 K (8.95 ± 4.00 °C; 48.11 ± 7.20 °F) (for a null albedo)[6] |

| Orbital elements | ||

| Semi-major axis | (a) | 0.02228038 (± 4.4e-7)[5] AU |

| Periastron | (q) | 0.022094 +0.0000206 −0.000021 AU |

| Apastron | (Q) | 0.022467 +0.0000206 −0.000021 AU |

| Eccentricity | (e) | 0.00837 (± 0.00093)[5] |

| Orbital period | (P) | 4.049959 (± 0.000078)[6] d |

| Inclination | (i) | 89.89 +0.08 −0.15[6]° |

| Other designations | ||

2MASS J23062928-0502285 d, 2MASSI J2306292-050227 d, 2MASSW J2306292-050227 d, 2MUDC 12171 d, K2-112 d | ||

| Discovery information | ||

| Discovery date | May 2, 2016 | |

| Discoverer(s) | ||

| Discovery method | Transit | |

| Discovery status | Published | |

| Database references | ||

| Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia | data | |

| SIMBAD | data | |

| Exoplanet Archive | data | |

| Open Exoplanet Catalogue | data | |

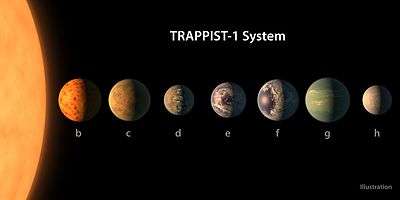

TRAPPIST-1d, also designated as 2MASS J23062928-0502285 d, is a small, water-rich, primarily rocky exoplanet orbiting within the habitable zone of the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 approximately 40 light-years (12.1 parsecs, or nearly 3.7336×1014 km) away from Earth in the constellation of Aquarius. The exoplanet was found by using the transit method, in which the dimming effect that a planet causes as it crosses in front of its star is measured. The first signs of the planet were announced in 2016, but it wasn't until the following years that the true nature of the planet was revealed. TRAPPIST-1d is the least massive planet of the system and has about 5% of its mass in water, likely in the form of a huge liquid ocean.[5] It is confirmed to have a compact, terrestrial atmosphere[7] and receives just 4.3% more sunlight than Earth, placing it within the habitable zone.[6]

Characteristics

Radius, mass, and temperature

TRAPPIST-1d was detected with the transit method, allowing scientists to accurately determine its radius. The planet is about 0.784 R⊕ with a small error margin of about 147 km. Transit timing variations and complex computer simulations helped accurately determine the mass of the planet, which led to scientists being able to calculate its density, surface gravity, and composition. TRAPPIST-1d is a mere 0.297 M⊕, making it one of the least massive exoplanets yet found. It has 61.6% the density of Earth (3.39 g/cm3) and just under half the gravity. Both its mass, density, and surface gravity are the lowest in the entire TRAPPIST-1 system. In addition, the density of TRAPPIST-1d indicates a mainly rocky composition, with about ≤5% of its mass in the form of water. The water of TRAPPIST-1d is likely in the form of a global ocean, but an ice shell (like TRAPPIST-1f, g, and h) or a steam atmosphere (like TRAPPIST-1b and c) cannot be ruled out.[5] TRAPPIST-1d has an equilibrium temperature of 282.1 K (9.0 °C; 48.1 °F), assuming an albedo of 0.[6] For an Earth-like albedo of 0.3, the planet's equilibrium temperature is around 258 K (−15 °C; 5 °F), very similar to Earth's at 255 K (−18 °C; −1 °F).[8]

Orbit

TRAPPIST-1d is a closely orbiting planet, with one full orbit taking just 4.05 days (about 97 hours) to complete.[6] It orbits at a distance of just 0.02228 AU from the host star, or about 2.2% the distance between Earth and the Sun.[5] For comparison, Mercury, our Solar System's innermost planet, takes 88 days to orbit at a distance of about 0.38 AU. The size of TRAPPIST-1 and the close orbit of TRAPPIST-1d around it means that the star as seen from the planet appears 5.5 times as large as the Sun from the Earth. While a planet at TRAPPIST-1d's distance from our Sun would be a scorched world, the low luminosity of TRAPPIST-1 means that the planet gets only 1.043 times the sunlight that Earth receives, placing it within the inner part of the conservative habitable zone.[6]

Host star

The planet orbits an (M-type) ultracool dwarf star named TRAPPIST-1. The star has a mass of 0.089 M☉ (close to the boundary between brown dwarfs and hydrogen-fusing stars) and a radius of 0.121 R☉. It has a temperature of 2,516 K (2,243 °C; 4,069 °F), and is between 3 and 8 billion years old. In comparison, the Sun is 4.6 billion years old[9] and has a temperature of 5778 K (5504.85 °C, 9940.73 °F).[10] The star is metal-rich, with a metallicity ([Fe/H]) of 0.04, or 109% the solar amount. This is particularly odd as such low-mass stars near the boundary between brown dwarfs and hydrogen-fusing stars should be expected to have considerly less metals than the Sun. Its luminosity (L☉) is 0.05% of that of the Sun.

Stars like TRAPPIST-1 have the ability to live up to 4–5 trillion years, 400–500 times longer than the Sun will live (which the Sun only has about 5.5 billion years of lifespan left (which is almost a halftime of life)).[11] Because of this ability to live for long periods of time, it is likely TRAPPIST-1 will be one of the last remaining stars when the Universe is much older than it is now, when the gas needed to form new stars will be exhausted, and the remaining ones begin to die off.

The star's apparent magnitude, or how bright it appears from Earth's perspective, is 18.8. Therefore, it is too dim to be seen with the naked eye.

The star is not just very small, and far away, it also emits comparatively little visible light, mainly shining in the invisible infrared. Even, from the close in proximity of TRAPPIST-1d, about 50 times closer than Earth is from the Sun, the planet receives less than 1% the visible light Earth sees from our Sun. This would probably make the days on TRAPPIST-1d never brighter than twilight is on Earth. However, that still means that TRAPPIST-1 could easily shine at least 3000 times brighter in the sky of TRAPPIST-1d than the full moon does in Earth's night sky.

Habitability

The exoplanet was announced to be orbiting on the inside part of the expected habitable zone of its parent star (the region where, with the correct conditions and atmospheric properties, liquid water may exist on the surface of the planet). The investigators' three-dimensional climate model resulted in a runaway greenhouse effect. However, a small quantity of water may have persisted in limited regions beyond the early hot phase in the planet's history.[12][13]

Later analyses that refined the parameters for the star and the planets revealed that TRAPPIST-1d likely can resist a runaway greenhouse effect, especially if it has an Earth-like albedo of ≥0.3. In addition, tidal heating from the host star could result in geothermal activity at the bottom of TRAPPIST-1d's oceans.[14]

Currently, TRAPPIST-1d is one of the most Earth-like exoplanets found. While being significantly smaller, it receives about the same amount of starlight as Earth and appears to be very similar in temperature as well. It does not have a large hydrogen-based atmosphere, which would render the planet uninhabitable if one were to exist. The planet also appears to be abundant in liquid water, having about 250 times more water than all of Earth's oceans.[5] TRAPPIST-1d has the highest Earth Similarity Index of any known exoplanet, at 0.91.[15] While the planet is most likely tidally locked, its atmosphere could be enough to transfer heat around the planet and keep the climate stable.

Discovery

A team of astronomers headed by Michaël Gillon of the Institut d’Astrophysique et Géophysique at the University of Liège[16] in Belgium used the TRAPPIST (Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope) telescope at the La Silla Observatory in the Atacama desert, Chile,[17] to observe TRAPPIST-1 and search for orbiting planets. By utilising transit photometry, they discovered three Earth-sized planets orbiting the dwarf star; the innermost two are tidally locked to their host star while the outermost appears to lie either within the system's habitable zone or just outside of it.[18][19] The team made their observations from September to December 2015 and published its findings in the May 2016 issue of the journal Nature.[17][20]

The original claim and presumed size of the planet was revised when the full seven-planet system was revealed in 2017:

- "We already knew that TRAPPIST-1, a small, faint star some 40 light years away, was special. In May 2016, a team led by Michaël Gillon at Belgium’s University of Liege announced it was closely orbited by three planets that are probably rocky: TRAPPIST-1b, c and d...

- "As the team kept watching shadow after shadow cross the star, three planets no longer seemed like enough to explain the pattern. “At some point we could not make sense of all these transits,” Gillon says.

- "Now, after using the space-based Spitzer telescope to stare at the system for almost three weeks straight, Gillon and his team have solved the problem: TRAPPIST-1 has four more planets.

- "The planets closest to the star, TRAPPIST-1b and c, are unchanged. But there’s a new third planet, which has taken the d moniker, and what had looked like d before turned out to be glimpses of e, f and g. There’s a planet h, too, drifting farthest away and only spotted once." [21]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Van Grootel, Valerie; Fernandes, Catarina S.; Gillon, Michaël; Jehin, Emmanuel; Scuflaire, Richard; et al. (5 December 2017). "Stellar parameters for TRAPPIST-1". arXiv:1712.01911 [astro-ph].

- 1 2 3 4 "Planet TRAPPIST-1 d". Exoplanet.eu. Retrieved 2016-05-06.

- ↑ Costa, E.; Mendez, R.A.; Jao, W.-C.; Henry, T.J.; Subasavage, J.P.; Ianna, P.A. (August 4, 2006). "The Solar Neighborhood. XVI. Parallaxes from CTIOPI: Final Results from the 1.5 m Telescope Program" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. The American Astronomical Society. 132 (3): 1234. Bibcode:2006AJ....132.1234C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.622.2310. doi:10.1086/505706.

- ↑ https://www.eso.org/public/archives/releases/sciencepapers/eso1615/eso1615a.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Grimm, Simon L.; Demory, Brice-Olivier; Gillon, Michael; Dorn, Caroline; Agol, Eric; Burdanov, Artem; Delrez, Laetitia; Sestovic, Marko; Triaud, Amaury H.M.J.; Turbet, Martin; Bolmont, Emeline; Caldas, Anthony; de Wit, Julien; Jehin, Emmanuel; Leconte, Jeremy; Raymond, Sean N.; Van Grootel, Valerie; Burgasser, Adam J.; Carey, Sean; Fabrycky, Daniel; Heng, Kevin; Hernandez, David M.; Ingalls, James G.; Lederer, Susan; Selsis, Franck; Queloz, Didier (5 February 2018). "The nature of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets". arXiv:1802.01377 [astro-ph.EP].

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Delrez, Laetitia; Gillon, Michael; H.M.J, Amaury; Brice-Oliver Demory, Triaud; de Wit, Julien; Ingalls, James; Agol, Eric; Bolmont, Emeline; Burdanov, Artem; Burgasser, Adam J.; Carey, Sean J.; Jehin, Emmanuel; Leconte, Jeremy; Lederer, Susan; Queloz, Didier; Selsis, Franck; Grootel, Valerie Van (9 January 2018). "Early 2017 observations of TRAPPIST-1 with Spitzer". arXiv:1801.02554 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ https://www.space.com/39613-trappist-1-planet-atmospheres-lack-hydrogen.html

- ↑ http://phl.upr.edu/projects/habitable-exoplanets-catalog/calculators

- ↑ Fraser Cain (16 September 2008). "How Old is the Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Fraser Cain (15 September 2008). "Temperature of the Sun". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory; Graves, Genevieve J. M. "Red Dwarfs and the End of the Main Sequence". Gravitational Collapse: From Massive Stars to Planets. Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. pp. 46–49. Bibcode:2004RMxAC..22...46A.

- ↑ Gillon, M.; Triaud, A. H. M. J.; Demory, B.-O.; Jehin, E.; Agol, E.; Deck, K. M.; Lederer, S. M.; De Wit, J.; Burdanov, A.; Ingalls, J. G.; Bolmont, E.; Leconte, J.; Raymond, S. N.; Selsis, F.; Turbet, M.; Barkaoui, K.; Burgasser, A.; Burleigh, M. R.; Carey, S. J.; Chaushev, A.; Copperwheat, C. M.; Delrez, L.; Fernandes, C. S.; Holdsworth, D. L.; Kotze, E. J.; Van Grootel, V.; Almleaky, Y.; Benkhaldoun, Z.; Magain, P.; Queloz, D. (2017). "Seven temperate terrestrial planets around the nearby ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1" (PDF). Nature. 542 (7642): 456. arXiv:1703.01424. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..456G. doi:10.1038/nature21360. PMC 5330437. PMID 28230125.

- ↑ "NASA telescope reveals largest batch of Earth-size, habitable-zone planets around single star". Exoplanet Exploration: Planets Beyond our Solar System (Press release). Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Barr, Amy C.; Dobos, Vera; Kiss, László L. (15 December 2017). "Interior structures and tidal heating in the TRAPPIST-1 planets". arXiv:1712.05641 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ http://phl.upr.edu/projects/habitable-exoplanets-catalog

- ↑ "AGO - Department of Astrophysics, Geophysics and Oceanography".

- 1 2 "Could these newly-discovered planets orbiting an ultracool dwarf host life?". The Guardian. 2 May 2016.

- ↑ "Three Potentially Habitable Worlds Found Around Nearby Ultracool Dwarf Star - Currently the best place to search for life beyond the Solar System". eso.org. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- ↑ "Three New Planets Are the Best Bets for Life". Popular Mechanics. 2016-05-02. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- ↑ Gillon, Michaël; Jehin, Emmanuël; et al. (2016). "Temperate Earth-sized planets transiting a nearby ultracool dwarf star". Nature. 533 (7602): 221–224. arXiv:1605.07211. Bibcode:2016Natur.533..221G. doi:10.1038/nature17448. PMID 27135924.

- ↑ New Scientist. Exoplanet discovery

.jpg)