Sukhoi Su-35

| Su-27M / Su-35 | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| A Russian Air Force Su-35S | |

| Role | Multi-role air superiority fighter |

| National origin | Soviet Union / Russia |

| Design group | Sukhoi Design Bureau |

| Built by | Komsomolsk-on-Amur Aircraft Production Association |

| First flight | Su-27M: 28 June 1988 Su-35S: 19 February 2008 |

| Introduction | February 2014 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Air Force People's Liberation Army Air Force |

| Produced | Su-27M: 1987–1995 Su-35S: 2007–present |

| Number built | Su-27M: 14[1] Su-35S: 85 (71 for Russia,[2][3][4] 14 for export[5]) |

| Unit cost | |

| Developed from | Sukhoi Su-27 |

| Variants | Sukhoi Su-37 |

The Sukhoi Su-35 (Russian: Сухой Су-35; NATO reporting name: Flanker-E) is the designation for two improved derivatives of the Su-27 air-defence fighter. They are single-seat, twin-engine, supermaneuverable aircraft, designed by the Sukhoi Design Bureau and built by the Komsomolsk-on-Amur Aircraft Plant.

The first variant was designed during the 1980s as an improvement on the Su-27 and was known as the Su-27M. This derivative incorporated canards and a multi-function radar that transformed the aircraft into a multi-role aircraft, which was structurally reinforced to cope with its greater weight. The first prototype made its maiden flight in June 1988. As the aircraft was not mass-produced due to the Dissolution of the Soviet Union, Sukhoi re-designated the aircraft as Su-35 to attract export orders. The fourteen aircraft produced were used for tests and demonstrations; one example had thrust-vectoring engines and the resultant Su-37 was used as a technology demonstrator. A sole Su-35UB two-seat trainer was also built in the late 1990s that resembled the Su-30MK family.

In 2003, Sukhoi embarked on a second modernization of the Su-27 to serve as an interim aircraft awaiting the development of the Sukhoi PAK FA (Su-57) program. Also known as Su-35, this version has a redesigned cockpit and weapons-control system compared to the Su-27M and features thrust-vectoring engines in place of the canards. The type made its first flight in February 2008; although the aircraft was designed for export, the Russian Air Force in 2009 became the launch customer of the aircraft, with the production version called Su-35S. The Chinese People's Liberation Army Air Force and the Indonesian Air Force have also ordered the aircraft.

Design and development

Upgraded Su-27

The first aircraft design to receive the Su-35 designation had its origins in the early-1980s, at a time when the Su-27 was being introduced into service with the Soviet Armed Forces. The definitive production version of the Su-27, which had the factory code of T-10S, started mass ("serial") production with the Komsomolsk-on-Amur Aircraft Production Association (KnAAPO) in 1983. The following year, this Su-27 version reached initial operational readiness with the Soviet Air Defence Forces.[9] Having begun work on an upgraded Su-27 variant in 1982,[10] the Sukhoi Design Bureau was instructed in December 1983 by the Soviet Council of Ministers to use the Su-27 as the basis for the development of the Su-27M (T-10M).[11] Nikolay Nikitin would lead the design effort throughout much of the project's existence, under the oversight of General Director Mikhail Simonov, who had been the chief designer of the Su-27.[12]

.png)

While sharing broadly the blended wing-body design of the Su-27, the Su-27M is visibly distinguished from the basic version by the addition of canards, which are small lifting surfaces, ahead of the wings. First tested in 1985 using an experimental aircraft,[9] the canards, in complement with the reshaped wing leading-edge extension, redirected the airflow in such a way so as to eliminate buffeting at high angles of attack and allowed the airframe to sustain 10-g manoeuvres (as opposed to 9 g on the Su-27) without the need for additional structural reinforcement.[13] More importantly, when working with the relaxed-stability design and the accompanying fly-by-wire flight-control system, the aerodynamic layout improved aircraft's manoeuvrability; it enabled the aircraft to briefly fly with its nose past the vertical while maintaining forward momentum. Because of this, theoretically, during combat the pilot could pitch the Su-27M up 120 degrees in under two seconds and fire missiles at the target.[14] Other notable visible changes compared to the T-10S design included taller vertical tails, provisions for in-flight refuelling and the use of two-wheel nose undercarriage to support the heavier airframe.[15][16]

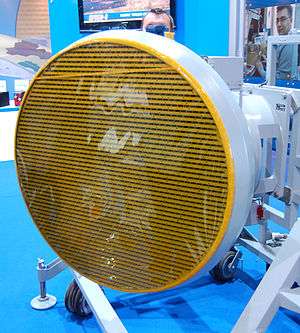

Besides the increase in manoeuvrability, another feature that distinguished the Su-27M from the original design was the new weapons-control system. The centrepiece of this system was the multi-function N011 Bars (literally "Panther") phased-array radar with pulse-Doppler tracking that allowed it to detect targets below the horizon. First installed on the third prototype, the radar transformed the Su-27M from simply being an air-defence fighter into a multi-role aircraft capable of attacking ground targets.[9][17] Compared to the N001 Myech ("Sword") radar of the Su-27, which could track 10 targets and only direct a two missiles towards one target at a time, the new radar could track fifteen targets and direct missiles towards six of them simultaneously.[9] The extra weight of the N011 radar at the front of the aircraft necessitated the addition of the canards; engineers would only later discover the aerodynamic advantages of these devices.[18][19] In addition, an N012 self-defence radar was housed in the rearward-projecting tail boom, making the aircraft the first in the world to have such a radar.[17] Other changes to the aircraft included the use of uprated turbofan engines, as well as the increased use of lightweight composites and aluminium-lithium alloys in the aircraft's structure.[15][20]

Testing and demonstration

In 1987, Sukhoi started converting the first prototype (designated T10M-1) from a T-10S airframe at its experimental plant in Moscow. Although it had canards, the first prototype, like several subsequent aircraft, lacked the many physical alterations of the new design.[21] It made its first flight after conversion on 28 June 1988, piloted by Oleg Tsoi, followed by the second prototype in January 1989.[22] Following the conversions of the two Su-27M prototypes, the actual production of the aircraft was transferred to the country's Far East where it was carried out by KnAAPO. The third aircraft (T10M-3), which was the first new-built Su-27M and first to be constructed by KnAAPO, made its first flight in April 1992.[22] By then, the Soviet Union had disintegrated, and the ensuing economic crisis in Russia throughout the 1990s meant that the original plan to mass-produce the aircraft between 1996 and 2005 was abandoned,[9] with the aircraft to serve as experimental test-beds to validate the canards, the flight-control system and thrust-vectoring technology.[15] In total, two prototypes, nine flying pre-production and three production aircraft were constructed by 1995;[18] the production aircraft were delivered in 1996 to the Russian Air Force for weapons testing.[23][1]

.jpg)

By the time of the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Sukhoi had been demonstrating the Su-27M to senior defence and government officials. With its debut to a Western audience at the 1992 Farnborough Airshow, the company redesignated the aircraft as Su-35.[24] The aircraft subsequently made flying demonstrations overseas in an effort to attract export orders, starting in November 1993 with Dubai, where Viktor Pugachev flew it in a mock aerial engagement with an Su-30MK in front of spectators.[25][26] The aircraft thereafter flew in Berlin and Paris, and would be a regular feature at Moscow's MAKS Air Show.[26] The Russian government cleared the aircraft for export during Sukhoi's unsuccessful sales campaign in South Korea during the late 1990s and early 2000s;[27] the company also marketed the aircraft to Brazil, China and the United Arab Emirates.[28]

As the flight-test programme of the Su-27M proceeded, engineers discovered that the pilot failed to maintain active control of the aircraft during certain manoeuvres, such as the Pugachev's Cobra. The eleventh Su-27M (T10M-11) was therefore installed with thrust-vectoring engine nozzles in 1995, and the resultant Su-37 technology demonstrator made its first flight on 2 April 1996.[29][30] It also tested the enhanced N011M radar, as did the twelfth developmental Su-27M.[28] The Su-37's ability to maintain a high angle of attack while flying at close to zero airspeed attracted considerable press attention.[31] It later received different engines and updated fly-by-wire controls and cockpit systems for evaluation.[28]

Apart from the single-seat design, a two-seat aircraft was also constructed. Working in cooperation with Sukhoi, KnAAPO's own engineers designed the Su-35UB so as to combine thrust-vectoring engines with features of the Su-27M. Modified from an Su-30MKK airframe, the aircraft made its first flight on 7 August 2000, and afterwards served as an avionics test-bed.[32] While the original Su-27M never entered mass production due to a lack of funding,[33] Sukhoi refined the Su-27M's use of canards and the Su-37's thrust-vectoring technology and later applied them to the Su-30MKI two-seat fighter for the Indian Air Force.[34] The tenth Su-27M (T10M-10) also served as a test-bed for the Saturn AL-41FS engine that is intended for the Sukhoi Su-57 (previously known under the acronym "PAK FA") jet fighter.[35]

Modernization

With the need to update Russia's ageing fleet of Su-27 aircraft, Sukhoi and KnAAPO in 2002 started integrating glass cockpits and improved weapons-control systems (to accommodate a greater variety of weapons) to existing air force aircraft. The Su-27SM, as the modified aircraft is called, made its first flight in December 2002.[36] The initial success of this project led Sukhoi in December 2003 to proceed with a follow-up modernization programme. Known internally as T-10BM,[18] the programme was aimed at a more thorough redesign of the airframe to narrow the qualitative gap between Russian aircraft and foreign so-called fourth-generation aircraft. The resultant design, also designated Su-35, would serve as an interim solution pending the introduction of the Sukhoi Su-57 fifth-generation fighter,[37][38] many features of which the aircraft would incorporate.[18] Additionally, the aircraft was to be a single-seat alternative to the two-seat design of the Su-30MK on the export market.[39][40]

In many respects, the T-10BM design outwardly resembles the Su-27 more than the Su-27M. During tests of the thrust-vectoring engines and the Su-27M's aerodynamic layout, Sukhoi had concluded that the loss of manoeuvrability due to the removal of the canards – the design of which imposed a weight penalty on the airframe – could be compensated for by the addition of thrust-vectoring nozzles.[N 1] Industry progress in the fields of avionics and radars have also reduced the weight and size of such components, which shifted the centre of gravity of an aircraft rearward.[42] Therefore, designers removed the canards (and the dorsal air brake) found on the Su-27M; the size of the vertical tails, aft-cockpit hump and tail boom were also reduced.[42] With such changes, as well as the increased use of aluminium and titanium alloys and composites, designers had reduced the empty weight of the aircraft,[43][44] while maintaining a similar maximum take-off weight to the Su-27M.

_(523-02).jpg)

While the Su-27M design had the avionics to give the aircraft the nominal designation as a multi-role fighter, flight tests with the Russian Air Force revealed difficulties in efficiently deploying the aircraft's armament. According to Aviation Week & Space Technology, air force pilots described weapons trials with the aircraft in Akhtubinsk and Lipetsk as a "negative experience", with a particular emphasis on the layout of the cockpit and its adverse impact on the workload of the single pilot.[41] Designers, test pilots and avionics software specialists therefore worked together to redesign the cockpit and its attendant systems and improve the human-machine interface. The information management system of aircraft's avionics suite had been changed so that it now has two digital computers which process information from the flight- and weapons-control systems. The information is then displayed on two 9 in × 12 in (23 cm × 30 cm) multi-function liquid crystal displays,[45] which replaced the smaller multi-function cathode-ray tube displays found on the Su-27M.[41] The pilot can also view critical flight information on the head-up display,[46] and is equipped with Hands On Throttle-And-Stick (HOTAS) controls.[45]

The Su-35 employs the powerful N035 Irbis-E ("Snow Leopard") passive electronically-scanned array (PESA) radar, which is a further development of the N011M radar that had been evaluated on Su-27M test-beds and constitutes the core of the Su-35's weapons-control system. It is capable of detecting an aerial target up to 400 km (250 mi; 220 nmi) away, and can track thirty airborne targets and engage eight of them simultaneously; in addition, the multi-function radar is capable of providing high-resolution images of the ground using synthetic aperture mode.[47] The aircraft is equipped with an OLS-35 optoelectronic targeting system ahead of the cockpit to provide other forms of tracking including infra-red search and track.[47] For defences against enemy tracking, the Su-35 is equipped with the L175M Khibiny-M electronic countermeasure system,[48] while engineers have applied radar-absorbent materials to the engine inlets and front stages of the engine compressor to halve the Su-35's frontal radar cross-section and minimise the detection range of enemy radars.[49] The multi-role Su-35 can deploy air-to-air missiles of up to 300-kilometre (190 mi) range, and can carry the heavy Oniks anti-ship cruise missile, as well as the multitude of air-to-ground weaponry.[50][51]

| "The classical air combat starts at high speed, but if you miss on the first shot—and the probability is there because there are maneuvers to avoid missiles—the combat will be more prolonged. After maneuvering, the aircraft will be at a lower speed, but both aircraft may be in a position where they cannot shoot. But supermaneuverability allows an aircraft to turn within three seconds and take another shot."[52] |

| — Sergey Bogdan, Sukhoi chief test pilot |

The Su-35 is powered by a pair of Saturn AL-41F1S, formerly known as izdeliye (Product) 117S, turbofan engines. While based on the AL-31F engine of the Su-27M, it shares some of the core design of Su-57's more-powerful Saturn AL-41F1 (izdeliye 117).[53] The aircraft is equipped with thrust-vectoring nozzles, which has their rotational axes canted at an angle, similar to the configuration on the Su-30MKI and Su-57. The nozzles operate in one plane for pitch, but the canting allows the aircraft to produce both roll and yaw by vectoring each engine nozzle differently.[54] The Su-35's thrust-vectoring system and integrated flight- and propulsion-control systems allow the aircraft to attain "supermaneuverability", enabling it to perform post-stall manoeuvres at low speeds. This differs from Western air combat doctrine, which emphasises the maintenance of a fighter aircraft's kinetic energy.[52]

The engine gives the Su-35 the limited ability to sustain supersonic speed without the use of afterburners.[43] According to Carlo Kopp of the think tank Air Power Australia, such a "supercruise" feature allows the Su-35 to engage an opponent at a greater speed and altitude and increases the range of its long-range missiles by 30–40 percent.[44] He cites the aircraft's mature airframe and carefully-balanced combination of advanced technology as allowing the Su-35 to achieve a favourable exchange rate against the F-35 stealth fighter.[55] A RAND Corporation study in 2008 found that the Su-35 could shoot down 2.4 F-35s for every aircraft lost;[56] however, the US Department of Defense and Lockheed Martin had refuted criticisms of the aircraft, claiming that it is 400 percent more effective in air-to-air combat than any other aircraft other than the F-22.[57]

Testing and production

Following the completion of design work, KnAAPO constructed the first prototype, which was finished in mid-2007. The prototype, Su-35-1, was then transferred to the Gromov Flight Research Institute at Zhukovsky Airfield, in preparation for its maiden flight.[58][59] On 19 February 2008, Sergey Bogdan took the aircraft aloft for its 55-minute first flight from Zhukovsky, accompanied by an Su-30MK2 acting as a chase plane.[58][60] Bogdan later piloted the second prototype on its maiden flight on 2 October from KnAAPO's Dzyomgi Airport.[61] The flight-test programme was expected to involve three flying prototypes, but on 26 April 2009, a day before its scheduled maiden flight, the fourth Su-35 (there's a static test aircraft) crashed during a taxi run at Dzyomgi Airport. The aircraft struck a barrier at the end of the runway and was destroyed by fire; the pilot ejected and sustained burn injuries.[62][63] A commission was opened to investigate the crash, but several sources initially speculated that the incident had been the result of a brake failure or a faulty fuel pump.[64]

.jpg)

The Su-35 project was aimed primarily at the export market.[65][66] During the early stages of the flight-test programme, Sukhoi estimated that there was such a market for 160 aircraft, with a particular emphasis on Latin America, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Some of the candidate countries, such as Algeria, Malaysia, and India, were already operators of the Su-30MK family.[67] As the aircraft was to be available for export starting in 2010,[68][69] the actual launch order for 48 Su-35S aircraft was placed by the Russian Defence Ministry at the 2009 MAKS Air Show (as part of a larger deal worth US$2.5 billion for 64 fighter aircraft).[70] During the type's international debut at the 2013 Paris Air Show, Mikhail Pogosyan, General Director of Sukhoi's parent company United Aircraft Corporation, stated that there was an estimated demand for 200 aircraft, split evenly between the domestic and export markets.[71] It was not until the end of 2015 when the first export contract was signed with China; by then, the Russian government had placed a follow-up order for 50 aircraft.[72]

Apart from the launch order at the 2009 MAKS Air Show, the Russian government and the state-owned VEB development bank agreed to provide Sukhoi with capital for the aircraft's production.[70] In November 2009, KnAAPO (which was renamed KnAAZ in 2013 after it became part of the Sukhoi Company) started manufacturing the first production aircraft,[73] the general assembly of which was completed in October 2010;[74] by then, pilots and engineers had successfully completed preliminary tests of the aircraft's systems.[75] The first Su-35S took its maiden flight in May 2011,[76] and would be delivered (along with other aircraft) to Akhtubinsk to start state joint tests with the Defence Ministry to prepare the aircraft for service. Because production of the Su-35S occurred alongside trials, some early-production aircraft were later modified as a result of such tests.[77]

Operational history

Russia

In 1996, three production Su-27Ms were delivered to the air force's 929th State Flight-Test Centre (GLITs) at Vladimirovka air base, Akhtubinsk, to perform weapons trials.[23] In 2001, the air force decided to transfer several Su-27Ms to re-equip the Russian Knights aerobatics team, and so the team's pilots took familiarisation flights with the aircraft.[78] The three production and two other pre-production Su-27Ms arrived at the team's Kubinka air base near Moscow in 2003. However, they were used as a source of spare parts for other aircraft in the demonstration fleet.[79]

In late May 2011, Sukhoi delivered the first Su-35S to Akhtubinsk to conduct state joint tests with the Defence Ministry to prepare the aircraft for operational service.[80] Before the start of the tests, the aircraft's Su-35's avionics and integrated defence systems were reportedly not up to the standard of American aircraft.[81] The first of two stages of the trials commenced in August 2011. By March 2012, the two prototypes and four production aircraft were conducting flights as the air force tested the type's technical characteristics,[80] which were assessed by the end of that year to have generally complied with requirements.[82][83] Of the batch of six production aircraft that were handed over in December 2012,[84] five flew to the Gromov Flight Research Institute in Zhukovsky where the aircraft would, in February 2013, start the second stage of the trials. This stage, which was scheduled to last eighteen months, would focus on the Su-35's weapons and manoeuvrability in combat.[83][85]

Twelve Su-35S fighters were delivered to the air force in December 2013,[86] followed in February 2014 by another twelve aircraft, ten of which were handed over to the 23rd Fighter Aviation Regiment stationed in the Far East with the remaining two tasked with carrying out the final phase of state joint tests.[77] The handover marked the official entry of the aircraft into operational service.[87] By then, 34 of the 48 aircraft originally ordered had been delivered with the remaining 14 due in 2015.[88] Several Su-35s were later transferred to Lipetsk to further develop combat tactics and to train service personnel.[89] The Su-35 is also permanently based at Besovets air base near the Finnish border,[90] and at Centralnaya Uglovaya air base near Vladivostok.[91]

The introduction of the Su-35 into service with the Russian Air Force is part of the state arms programme for 2011–2020 that was formulated following the war with Georgia in 2008.[92] It would be delivered alongside the heavier Su-34 strike aircraft,[93] as well as the Su-30M2 and Su-30SM. The latter two are domestic variants of KnAAPO's Su-30MK2 and Irkut's Su-30MKI two-seat export aircraft. According to reports, the simultaneous acquisition of three fighter derivatives of the original Su-27 was to support the two aircraft manufacturers amidst a slump in export orders.[87] The Su-30M2 serves as a trainer aircraft for the Su-35,[93] while several of the Su-30SMs replaced the Su-27s of the Russian Knights who selected the type instead of the Su-35 because of the convenience of a two-seat design.[94]

In January 2016, Russia, for the first time in combat conditions, deployed four Su-35S planes to Khmeimim air base in Syria as part of Russian air operations in the country.[95] This occurred following an increase in tension between Russia and Turkey as a result of reported incursions by Russian aircraft into Turkish airspace.[96] The aircraft complemented the Su-30SMs in flying combat air patrols and providing protection to other aircraft that were conducting bombing missions.[97] As a result of operations in Syria, problems were identified with the aircraft's avionics and were subsequently rectified.[98] The aircraft reportedly attained full operational capability in late 2018.[99][100][101]

China

During the early 1990s, a sales arrangement of the Su-27M to China was discussed. Sukhoi officials in 1995 announced their proposal to co-produce the Su-27M with China, contingent on Beijing's agreement to purchase 120 aircraft.[102] However, it was alleged that the Russian Foreign Ministry blocked the sale of the Su-27M and Tupolev Tu-22M bomber over concerns about the arrangements for Chinese production of the Su-27.[103]

In November 2015, China became the first export customer for the Su-35 when the Russian and Chinese governments signed a contract worth $2 billion for the purchase of 24 aircraft for the People's Liberation Army Air Force.[104][105] Although Chinese officials had first shown interest in the modernized Su-35 design in 2006,[106] it was not until 2010 that Rosoboronexport, the Russian state agency responsible for the export and import of defence products, was ready to start talks with the Chinese government on the sale of the Su-35.[107] Russian officials publicly confirmed that talks had been going on in 2012, when a protocol agreement on the purchase of the aircraft was signed.[108] There were subsequent media reports and official remarks that the two countries had signed a contract and deliveries of the aircraft were imminent,[109][110] but negotiations would not actually conclude until 2015.

Discussions over the sale of the Su-35 proved protracted due to concerns over intellectual property rights. As China had reverse engineered the Su-27SK and Su-33 to create the J-11B and J-15, respectively,[111] there were concerns that China would copy the airframe and offer the copied design on the export market. At one stage Rosoboronexport demanded that China provide a legally binding guarantee against copying.[111] However, industry sources believed that Chinese industry was interested in the AL-41FS1 engine and Irbis-E radar.[108][112] According to The Diplomat, China was specifically interested in the engine of the Su-35, as the country was already test flying the J-11D. While the aircraft reportedly has less range, payload and manoeuvrability than the Su-35, the J-11D has an active electronically-scanned array radar, instead of the less-advanced PESA radar as found on the Su-35.[113] Various reports have drawn attention to the need for Chinese industry to close the technological gap between its engine industry and those of the US, Europe and Russia.[105][108] Rosoboronexport insisted on China purchasing a minimum of 48 aircraft to offset risks of copying. After the Kremlin intervened in late 2012, the minimum number of aircraft was lowered to 24.[114] Another seemingly-intractable problem was the Chinese insistence that the aircraft include Chinese-made components and avionics. The Kremlin again intervened and conceded to such demands and allowed the deal to proceed. This was viewed as a major concession since the sales of such components are reportedly lucrative.[108] The contract did not include any technology transfer.[106]

At the end of January 2016, the Chinese military for the first time confirmed it had received four Russian-made Su-35 fighter jets on 25 December 2016.[115][116] Simultaneously, the People's Liberation Army's website opined that with the commissioning of the J-20, Russia had understood that the Su-35 would "lose its value on the Chinese market in the near future"; the article said, "Therefore we hope very much that Su-35 will be the last (combat) aircraft China imports."[115] However, the U.S. government′s Fact Sheet document published pursuant to the CAATSA-mandated sanctions in September 2018 said: ″China took delivery from Russia of ten Su-35 combat aircraft in December 2017″.[117] The Su-35S officially entered service with PLAAF in April 2018.[118]

On 20 September 2018, the U.S. imposed sanctions on China′s Equipment Development Department and its director, Li Shangfu, for engaging in ″significant transactions″ with Rosoboronexport, specifically naming China’s purchase of ten SU-35 combat aircraft in 2017 as well as S-400 surface-to-air missile system-related equipment in 2018.[119][117]

Indonesia

In late 2014, Russia offered the Su-35 to Indonesia as the country sought to replace its ageing F-5E Tiger II fleet.[120] The following year, the Indonesian Ministry of Defence selected the Su-35 ahead of the Eurofighter Typhoon, Dassault Rafale, F-16, and Saab JAS 39 Gripen; the Defence Ministry cited the Indonesian Air Force's familiarity with the Su-27SK and Su-30MK2 as the reason for the aircraft's selection.[121][122] By mid-2017, negotiations between the two parties for the sale of the Su-35 had reached an advanced stage,[123] with the Indonesian government later agreed in principle to conduct a barter trade of agricultural products for a reported eleven aircraft.[124][125] In February 2018, Russia and Indonesia finalised the Su-35 purchase contract for 11 aircraft, worth $1.14 billion. The first delivery is expected by October 2018.[126][127]

Potential operators

United Arab Emirates

In the mid-1990s, the United Arab Emirates evaluated the Su-27M,[128] but later acquired the Mirage 2000 due to the country's close relationship with France.[28] In 2015, its officials entered into negotiations with their Russian counterparts about the possible contract for the modernized Su-35.[129] In February 2017, the country signed a preliminary agreement for the purchase of a number of Su-35s, later reported to be 24,[130] and also signed an agreement with Rostec, Russia's state-owned corporation responsible for the development of advanced industrial products, to develop a fifth-generation aircraft based on the MiG-29.[131]

India

India has been reluctant to order the Sukhoi/HAL FGFA due to high cost, and it has been reported that India and Russia are studying an upgrade to the Su-35 with stealth technology (similar to the F-15 Silent Eagle) as a more affordable alternative to the FGFA (Su-57).[132]

Others

Following the deployment to Syria of several new Russian military systems, various countries had reportedly expressed interest in the Su-35. These countries included Algeria, Egypt, and Vietnam.[133][134][135] According to Kommersant, the Algerian military had requested an Su-35 for testing in February 2016; the country was satisfied with the fighter's flight characteristics and so Moscow is waiting for a formal application.[133] Other countries that had also expressed interest in the aircraft include Kazakhstan,[136] North Korea,[137] and Pakistan, although a Russian official denied that the country was in talks with the latter about the Su-35.[138] Sudan has reportedly also expressed an interest in acquiring of the Su-35 fighters during the Sudanese president Omar Hassan al-Bashir's visitation of Moscow in November 2017.[139]

Failed bids

Brazil

In the mid-1990s, Brazilian and Russian authorities conducted talks on the possible acquisition of the Su-27M.[140] In 2001, the Brazilian government launched the F-X tender, the objective of which was to procure at least twelve aircraft to replace the Brazilian Air Force's ageing aircraft, primarily the Mirage IIIs.[141][142] Since the Brazilian government was also looking to develop the country's aerospace and defence industries, Sukhoi partnered with the Brazilian defence contractor Avibras during the tender. The two companies submitted the Su-27M to the US$700-million tender, and included an offset agreement wherein the Brazilian industry would have participated in the manufacturing of certain aircraft equipment.[143] The tender was suspended in 2003 because of domestic political issues and then scrapped in 2005, pending the availability of new fighters.[141] The Su-27M was preferred over the next favourite, the Mirage 2000BR;[142] had the aircraft been purchased, it would have been the first heavy fighter delivered to Latin America.[140]

With the tender relaunched in 2007 as the F-X2 competition, the Brazilian Defence Ministry looked to purchase at least 36 aircraft – with a potential for 84 additional aircraft – to replace the country's A-1Ms, F-5BRs, and Mirage IIIs. Among the participants were the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, F-16BR, JAS Gripen NG, Dassault Rafale, Eurofighter Typhoon and the modernized Su-35.[144] Although the Brazilian government eliminated the Su-35 in 2008,[145] Rosoboronexport subsequently offered to sell the country 120 aircraft with full technology transfer,[146] as well as participation in the PAK FA programme.[147] In December 2013, the Gripen NG light fighter was selected because of its low cost and the transfer of technology to the Brazilian industry.[148]

Others

In 1996, Russia submitted the Su-27M and Su-37 for South Korea's F-X programme, which sought a 40-aircraft replacement for the Republic of Korea Air Force's F-4D/Es, RF-4Cs and F-5E/Fs. The two Russian designs competed against the Dassault Rafale, Eurofighter Typhoon, and F-15K Slam Eagle.[149] Sukhoi proposed a design which featured a phased-grid radar and thrust-vectoring engines, and offered full technology transfer as well as final assembly in South Korea. The US$5 billion contract would have been partially financed through a debt-reduction deal on money Russia owed to South Korea.[150][151] However, the Su-27M was eliminated early in the competition, which was won by the F-15K.[152]

A country that had been reported to be a likely early export customer for the modernized Su-35 was Venezuela. The Venezuelan government of Hugo Chavez in July 2006 placed an order for 24 Su-30MK2s to replace its fleet of F-16s that were subjected to a US arms embargo.[153] The aircraft were delivered to the Venezuelan Air Force from 2006 to 2008.[154] The country was expected to follow up with a second order for the same type, or make a purchase of the Su-35.[155] Despite subsequent reports that the Venezuelan government were interested in the aircraft and had placed an order for the Su-35,[156][157] the country was negotiating with Russia in 2016 for the Su-30 aircraft instead.[154]

Libya was also expected to be an early export customer for twelve to fifteen Su-35s along with other Russian weapons; however, the civil war in Libya and the resulting military intervention cancelled such plans.[158] Russia has also offered the modernized Su-35 to India, Malaysia, and Greece;[67][159] no firm contracts have materialised, with the first two countries having been occupied with other fighter projects and unlikely to procure the modernized Su-35.[40]

Variants

- Su-27M/Su-35

- Single-seat fighter design with a factory code of T-10M (Modernizerovany, "Upgraded"). The first two prototypes had a new forward fuselage, canards and updated fly-by-wire flight-control systems. Like three of KNAAPO's nine flying pre-production aircraft (T10M-5, T10M-6 and T10M-7), they were converted from Su-27 airframes.[160][161] The third aircraft (T10M-3) was the first of seven pre-production aircraft to have the taller vertical tails, two-wheel nose undercarriage and in-flight refuel capability.[22] The Su-27M was powered by AL-31FM turbofan engines.[20] Two prototypes, nine pre-production and three production aircraft were constructed by 1995;[18] two static-test aircraft was also constructed (T10M-0 and T10M-4).[162] The aircraft did not enter mass production.

- Su-37

- Technology demonstrator, converted from the eleventh developmental Su-27M (T10M-11). The Su-37 featured a digital fly-by-wire flight-control system, a glass cockpit, the N011M radar, and AL-31FP engines with thrust-vectoring nozzles.[163] The aircraft was later fitted with standard-production AL-31F engines, and had its flight-control system and cockpit systems revised.[164]

- Su-35UB

- Two-seat trainer designed and built by KnAAPO. The single aircraft (T-10UBM-1) featured the canards and taller vertical tails of the Su-27M and a forward fuselage similar to the Su-30MKK. The Su-35UB also shared the avionics suite of the Su-30MKK, although it had a different fly-by-wire flight-control system to accommodate the canards.[165] The aircraft was powered by AL-31FP engines with thrust-vectoring nozzles.[166] Although a training aircraft, the Su-35UB was designed to be fully combat-capable.[165]

- Su-35BM

- Single-seat fighter that is a major redesign of the original Su-27. The type features significant modifications to the airframe, including the removal of canards and dorsal air brake as found on the Su-27M. It features the updated N035 Irbis-E radar and a redesigned cockpit. The aircraft is powered by thrust-vectoring AL-41F1S turbofan engines that are capable of supercruise. Also known as T-10BM (Bolshaya Modernizatsiya, "Major Modernization"), Su-35BM is not the actual designation used by Sukhoi, who markets the aircraft as "Su-35".[70][167]

- Su-35S

- Designation of production T-10BM design for the Russian Air Force. According to Aviation Week & Space Technology, "S" stands for Stroyevoy ("Combatant").[112]

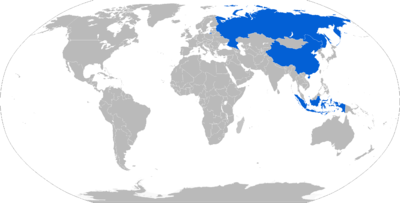

Operators

- People's Liberation Army Air Force – 24 Su-35S ordered in 2015. 14 aircraft in inventory as of December 2017.[5]

- Indonesian Air Force – confirmed in August 2017 it will buy 11 Su-35S fighters.[168] The contract was signed in February 2018 with first deliveries expected by October 2018.[126][127]

- Russian Air Force – 71 Su-35S in inventory as of July 2018.[2][3][4] The second order for 50 aircraft finalised in January 2016 is to increase the number to 98 of the variant; the rate of delivery should be 10 aircraft per year starting in the same year.[72]

- 23rd Fighter Aviation Regiment – Dzyomgi Airport, Komsomolsk-on-Amur[77]

- 22nd Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment – Centralnaya Uglovaya air base, Vladivostok[91]

- 159th Fighter Aviation Regiment – Besovets air base, Petrozavodsk[169]

- 4th Centre for Combat Employment and Retraining of Personnel – Lipetsk air base, Lipetsk

- 929th State Flight-Test Centre – Vladimirovka air base, Akhtubinsk

Specifications (Su-35S)

Data from KnAAPO,[46][170] Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2013[171]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 21.9 m (72 ft 11 in)

- Wingspan: (with wingtip pods) 15.3 m (50 ft 2 in)

- Height: 5.9 m (19 ft 5 in)

- Wing area: 62 m² (667 ft²)

- Empty weight: 17,200 kg (37,920 lb)

- Loaded weight: 25,300 kg (56,660 lb) at 50% internal fuel

- Max. takeoff weight: 34,500 kg (76,060 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 11,500 kg (25,400 lb) internally

- Powerplant: 2 × Saturn AL-41F1S afterburning turbofans

- Dry thrust: 86.3 kN (19,400 lbf) each

- Thrust with afterburner: 142 kN (31,900 lbf) each

Performance

- Maximum speed:

- At altitude: Mach 2.25 (2,400 km/h; 1,490 mph)

- At sea level: Mach 1.13 (1,400 km/h; 870 mph)

- Range:

- At altitude: 3,600 km (2,240 mi; 1,940 nmi)

- At sea level: 1,580 km (980 mi; 850 nmi)

- Combat radius: around 1,500 km[172] (932 mi; 810 nmi)

- Ferry range: 4,500 km (2,800 mi; 2,430 nmi) with 2 external fuel tanks

- Service ceiling: 18,000 m (59,100 ft)

- Rate of climb: >280 m/s (>55,000 ft/min)

- Wing loading:

- With 50% fuel: 408 kg/m² (84.9 lb/ft²)

- With full internal fuel: 500.8 kg/m² ()

- Thrust/weight: 1.13 at 50% fuel (0.92 with full internal fuel)

- Maximum g-load: +9 g

Armament

- Guns: 1 × internal 30 mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-30-1 autocannon with 150 rounds

- Hardpoints: 12 hardpoints, consisting of 2 wingtip rails, and 10 wing and fuselage stations with a capacity of 8,000 kg (17,630 lb) of ordnance and provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: S-25

- Missiles:

- Bombs:

- 8 × KAB-500KR TV-guided bombs

- 8 × KAB-500L laser-guided bombs

- 8 × KAB-500OD guided bombs

- 8 × KAB-500S-E satellite-guided bombs

- 3 × KAB-1500KR TV-guided bombs

- 3 × KAB-1500L laser-guided bombs

- GBU-500 laser-guided bomb

- GBU-500T TV-guided bomb

- GBU-1000 laser-guided bomb

- GBU-1000T TV-guided bomb

Avionics

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

Footnotes

References

- 1 2 Один из первых Су-35 продолжает летать. bmpd (blog) (in Russian). Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- 1 2 Шесть новых Су-35С идут в Карелию. bmpd (blog) (in Russian). Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. 31 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- 1 2 Полк на аэродроме Бесовец получил еще шесть истребителей Су-35С. bmpd (blog) (in Russian). Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- 1 2 Полк на аэродроме Бесовец получил еще пять истребителей Су-35С. bmpd (blog) (in Russian). Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. 14 July 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- 1 2 Китай получил уже 14 истребителей Су-35. bmpd (blog) (in Russian). Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. 2 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ На МАКСе заключат контракты на 64 российских истребителя. Lenta.ru (in Russian). 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "Russian Defense Ministry orders 64 Su-family fighters". RIA Novosti. 18 August 2009. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ http://eng.mil.ru/en/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12152160@egNews

- 1 2 3 4 5 Butowski, Piotr (1 November 1999). "Dominance by design: the reign of Russia's 'Flankers' – PART ONE". Jane's Intelligence Review. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. 11 (11). ISSN 1350-6226.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 69.

- ↑ Andrews 2003, p. 39.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 58, 122.

- ↑ Fink 1993, p. 45.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 122–123.

- 1 2 3 Williams 2002, p. 119.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 123, 127.

- 1 2 Gordon 2007, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Butowski 2004, p. 38.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 69.

- 1 2 Gordon 2007, p. 123.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 126–127.

- 1 2 3 Gordon 2007, p. 128.

- 1 2 Gordon 2007, p. 366.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 129–131.

- ↑ Fink 1993, p. 44.

- 1 2 Gordon 2007, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Flight International 2001, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Andrews 2003, pp. 58.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 142, 144.

- ↑ Velovich 1996, p. 16.

- ↑ Novichkov 1996, p. 52.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Barrie 1997, p. 8.

- ↑ Andrews 2003, p. 47.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 173.

- ↑ Fiszer 2004, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Fiszer 2004, p. 53.

- ↑ Butowski 2007, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Kramnik, Ilya (13 February 2008). Большая модернизация: ВВС России готовятся к государственным испытаниям истребителя СУ-35БМ. Lenta.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Russia's Su-35 Super-Flanker: Mystery Fighter No More". Defense Industry Daily. 27 March 2013. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 Barrie 2003, p. 39:

- 1 2 Butowski 2004, p. 39.

- 1 2 Karnozov, Vladimir (4 September 2007). "Sukhoi unveils 'supercruising' Su-35-1 multi-role fighter". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- 1 2 Kopp 2010, p. 9.

- 1 2 "Su-35". Sukhoi. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Su-35: Multifunctional Super-Maneuverable Fighter" (PDF). KnAAPO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- 1 2 Gordon 2007, p. 175.

- 1 2 "Sukhoi begins flight testing of Su-35S variant". Defenceweb.co.za. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Sweetman 2004, p. 26.

- ↑ Butowski 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 175–176.

- 1 2 Sweetman 2013, p. 33.

- ↑ Butowski 2004, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Sweetman 2013, p. 44.

- ↑ Kopp 2010, p. 10.

- ↑ Archibald 2016, p. 13.

- ↑ Wolf, Jim (21 September 2008). "Pentagon, Lockheed rebut F-35 fighter jet critics". Reuters. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

Citing U.S. Air Force analyses, he said the F-35 is at least 400 percent more effective in air-to-air combat capability than the best fighters currently available in the international market, including Sukhois.

- 1 2 Fomin 2008, p. 28.

- ↑ Usov, Pavel (16 February 2007). На КнААПО поступят двигатели для Су-35. Kommersant (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Начались испытания новой "сушки". Kommersant (in Russian). 19 December 2007. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Начались испытания второго летного образца новейшего Су-35 (Press release) (in Russian). Sukhoi. 3 October 2008. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Nechayev, Gennady (27 April 2009). Полностью разрушился и сгорел. Vzglyad (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Doronin, Nina (27 April 2009). В ходе испытаний на заводском аэродроме сгорел истребитель Су-35. Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Shcherbakov, Dmitriy (28 April 2009). Истребитель сгорел перед первым полетом. Kommersant (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ↑ Jennings, Gareth (19 June 2013). "Paris Air Show 2013: Le Bourget debut for Su-35". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. 50 (29). ISSN 2048-3430.

Also referred to as the Su-35S 'Super Flanker' (and sometimes the Su-35C), the Sukhoi was originally conceived purely for export sales, with China and Venezuela expressing interest.

- ↑ Butowski 2004, p. 40.

- 1 2 "Russia may export new Su-35 fighters to India, Malaysia, Algeria". RIA Novosti. 15 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 111.

- ↑ Zaitse, Yury (21 September 2007). "Sukhoi Su-35 fighter: winging its way into a new era". RIA Novosti. Archived from the original on 2 October 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Sukhoi signs record $2.5 billion deal with Russian defense ministry". RIA Novosti. 18 August 2009. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ "Su-35 Begins Global Journey". Flight Daily News. Sutton, UK: Reed Business Information. 20 June 2013. pp. 16–17.

The head of Sukhoi's parent company, United Aircraft, is forecasting 200 sales of the type, split 50:50 between domestic and export.

Missing or empty|url=(help) - 1 2 Pyadushkin, Maxim (12 January 2016). "Russia Places New Order For 50 Su-35S Fighters". Aerospace Daily & Defense Report. Aviation Week. Retrieved 29 July 2017. (Registration required (help)).

- ↑ "Sukhoi launches production of Su-35 for Russia". Defence Talk. 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "Sukhoi completed general units' assembly of the first production Su-35S" (Press release). Sukhoi. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "Sukhoi is completing preliminary tests of the Su-35" (Press release). Sukhoi. 20 July 2010. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "Russia begins test flights of Su-35S series fighter". RIA Novosti. 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 Fomin 2014, p. 37.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 365–366.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 137, 141.

- 1 2 Fomin 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ "Russian AF chief: US fighters superior to Su-35S" (blog). Flightglobal. 9 August 2011. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

The Su-35S avionics and integrated defence system is inferior to "American fighters of the same type", Zelin said.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Continues Tests of Su-35 Fighter Jet". RIA Novosti. 8 August 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- 1 2 Госиспытания истребителя Су-35С завершатся в 2015 году. Lenta.ru (in Russian). 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Delivered 6 Su-35S to the Ministry of Defense" (Press release). Sukhoi. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Mikhailov, Alexey (20 February 2013). "ВВС начали отработку сверхманевренного ближнего боя на Cу-35C". Izvestia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "TASS: Russia – Sukhoi supplies 12 Su-35 jet fighters to Russian Air Force in 2013". TASS. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 Newdick, Thomas (21 February 2014). "Russia's New Air Force Is a Mystery". War is Boring. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ↑ "Russia Arms Air Regiment in Far East With Su-35S Fighter Jets". Sputnik News. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Fomin 2014, p. 36.

- ↑ "New Generation Fighter Aircrafts [sic] Su-35 Were Added to Karelian Air Regiment" (Press release). Government of the Republic of Karelia. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- 1 2 "Pilots of the Eastern MD performed aerobatics over the Bay of Ayax in Vladivistok" (Press release). Russian Ministry of Defence. 5 September 2017. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Litovkin, Dmitry (20 January 2009). Армия станет "триллионером". Izvestia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- 1 2 Pyadushkin 2010, p. 28.

- ↑ Litovkin, Dmitry; Litovkin, Nikolai (24 March 2017). "Russian Knights demonstrate their new Su-30SM at Malaysian trade fair". Russia Behind the News. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ↑ "Turkish artillery shells Syrian territory – Russian military presents video proof". RT. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ de Larrinaga, Nicholas; O'Connor, Sean (3 February 2016). "Russia deploys Su-35S fighters to Syria". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. 53 (13). ISSN 2048-3430.

- ↑ Johnson, Reuben (10 February 2016). "New Fighter Aircraft to Expand Russian Air Campaign in Syria". Washington Free Beacon. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ Nikolsky, Alexey (24 May 2017). В боевых действиях в Сирии участвовали практически все летчики российских ВКС. Vedomosti (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ↑ "Russia's advanced Sukhoi Su-35S fighter put into operation". TASS. 19 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ http://www.armstrade.org/includes/periodics/news/2018/0404/115546147/detail.shtml

- ↑ http://www.armstrade.org/includes/periodics/news/2018/1012/100049102/detail.shtml

- ↑ Gill and Kim 1995, p. 60.

- ↑ Zhao 2004, p. 216.

- ↑ "Russia inks contract with China on Su-35 deliveries". TASS. 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- 1 2 Stolyarov, Gleb (19 November 2015). "UPDATE 2-Russia, China sign contract worth over $2 bln for Su-35 fighter jets -source". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- 1 2 Minnick, Wendell (20 November 2015). "Russia-China Su-35 Deal Raises Reverse Engineering Issue". Defense News. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ↑ "Russia ready to sell Su-35 fighter jets to China". RIA Novosti. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Johnson, Reuben (25 November 2015). "Su-35 deal signals PLAAF's lack of faith in Chinese defence sector". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. 53 (3). ISSN 2048-3430.

- ↑ Choi, Chi-yuk (26 March 2013). "China to buy Lada-class subs, Su-35 fighters from Russia". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Reuben (11 September 2013). "Reports of Su-35 sale to China met with scepticism". IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly. Coulsdon, UK: Jane’s Information Group. 50 (41). ISSN 2048-3430.

- 1 2 Johnson, Reuben (14 March 2012). "Russian industry wary of Su-35 sale to China". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. 49 (14). ISSN 2048-3430.

- 1 2 Pyadushkin 2014, p. 19.

- ↑ Sloman, Jesse; Dickey, Lauren (1 June 2015). "Why China's Air Force Needs Russia's SU-35". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ Karnozov, Vladimir (14 December 2012). "Sukhoi Nears Deal with China on Su-35 Fighters". AIN Online. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- 1 2 Zhao, Lei (6 January 2017). "Air Force receives 4 of Russia's latest fighters". China Daily. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ "PLA news portal: Su-35 intended to be last type of imported fighter". People's Daily. 30 December 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- 1 2 CAATSA Section 231: "Addition of 33 Entities and Individuals to the List of Specified Persons and Imposition of Sanctions on the Equipment Development Department" U.S. Department of State, September 20, 2018.

- ↑ http://www.airrecognition.com/index.php/archive-world-worldwide-news-air-force-aviation-aerospace-air-military-defence-industry/global-defense-security-news/global-news-2018/may/4272-su-35s-fighter-jets-officially-entered-service-with-plaaf.html

- ↑ "U.S. sanctions China for buying Russian fighter jets, missiles". Reuters, 20 September 2018.

- ↑ Grevatt, Jon (5 November 2014). "IndoDefence 2014: UAC announces Su-35 bid for Indonesian fighter competition". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. 51 (50). ISSN 2048-3430.

- ↑ "Kemhan Akan Ganti F-5 dengan Sukhoi SU-35". BeritaSatu (in Indonesian). 2 September 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ Grevatt, Jon (2 September 2015). "Indonesia selects Su-35 to meet air combat requirement". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. 52 (42). ISSN 2048-3430.

- ↑ "Moscow to ink contract on Su-35 jet deliveries to Indonesia this year". TASS. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ↑ "Indonesia to barter coffee, CPO for Russian jet fighters". Jakarta Post. 4 August 2017. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017.

- ↑ "Индонезия закупает 11 истребителей Су-35 за 1,14 миллиарда долларов". bmpd.livejournal.com. 23 August 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- 1 2 Grevatt, Jon (15 February 2018). "Indonesia finalises contract to procure Su-35 fighter aircraft". IHS Jane's 360. Bangkok. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- 1 2 Stocker, Joanne (15 February 2018). "Russia and Indonesia finalize Su-35 contract". The Defense Post. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Osborne, Tony (21 February 2017). "Russia, UAE To Partner On Fighter Development". Aerospace Daily & Defense Report. Aviation Week. (Registration required (help)).

- ↑ "Russia Negotiating With UAE Over Delivery of Su-35 Jets". Sputnik News. 8 November 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Russia plans to deliver 24 Su-35 fighter jets to UAE – FSMTC". Interfax. 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Yousef, Deena Kamel; Jasper, Christopher. "U.A.E. to Build Russian Warplane as Mideast Tensions Rise". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/could-russia-design-a-fifth-generation-variant-of-the-su-35-for-india/

- 1 2 Safranov, Ivan (4 March 2016). "Без кредита не взлететь". Kommersant (in Russian). Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ Litovkin, Nikolai; Egorova, Kira (27 June 2016). "Russian aircraft sales boosted by Syrian campaign". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ Nkala, Oscar (3 May 2016). "Algeria to test Su-35 fighter ahead of possible acquisition". Defenceweb.co.za. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "Arms Trade; Kazakh Defense Ministry interested in buying batch of Su-35 fighter jets". Russia & CIS Defense Industry Weekly. Interfax. 3 June 2016.

- ↑ "North Korea asked Russia for Su-35 fighter jet supplies – reports". TASS. 9 January 2015. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ "Russia not holding talks with Pakistan on supply of Su-35 jets". Sputnik News. 19 October 2016. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ↑ "Sudan seeking Su-35s". Defence Web. 29 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- 1 2 Lantratov, Constantine (31 March 2004). ""Сухой" против EmBrAer". Kommersant (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- 1 2 Rivers 2005, p. 18.

- 1 2 Lantratov, Constantine (28 February 2005). Бразилии не нужны новые истребители. Kommersant (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Komarov 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Истребитель Су-35 вернется в тендер ВВС Бразилии. Lenta.ru (in Russian). 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen (6 October 2008). "Brazil names three finalists for F-X2 contract, rejects three others". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ "Entrevista com Anatoly Isaikin Diretor General da EEFU Rosoboronexport sobre o Programa F-X2". DefesaNet (in Portuguese). 6 October 2009. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "Russia to pitch T-50 for Brazilian fighter deal". Flightglobal. 16 October 2016. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ↑ Salles, Filipe (18 December 2013). "Saab wins Brazil's F-X2 fighter contest with Gripen NG". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ↑ Sherman 2001, p. 22.

- ↑ Joo and Kwak 2001, p. 205.

- ↑ Gethin 1998, p. 32.

- ↑ Govindasamy, Siva (22 October 2007). "South Korean F-15K deal may close by end 2007". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Mader 2007, p. 102.

- 1 2 "Moscow, Caracas Complete Negotiations on 12 Su-30 Fighter Jets Deal". Sputnik News. 23 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Mader 2007, p. 103.

- ↑ "Venezuela's Chavez Eyes Russian Su-35 Fighters". RIA Novosti. 19 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Sweeney, Jack (15 October 2008). "Venezuela buys Russian aircraft, tanks to boost power". United Press International. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Russia big loser in Arab arms market slump". United Press International. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "Σαράντα οκτώ Su-35 παραδίδονται το 2015 – Υποψήφιο στην αξιολόγηση της Π.Α – Video: Su-35 Vs EF-2000". Defencenet.gr (in Greek). 20 September 2010. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Andrews 2003, p. 57.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 129.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 129, 591.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 151, 154, 158.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, pp. 170–171.

- 1 2 Andrews 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 172.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen (20 August 2009). "Russia signs $2.5 billion deal for 64 Sukhoi fighters". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ "Value of Indonesian Su-35 buy pegged at $1.14 billion". Flightglobal.com. 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- ↑ "ВКС России получили первые четыре Су-35 по новому контракту". Lenta.ru (in Russian). 12 November 2016. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ "Su-35". KnAAPO. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Su-35", Jane's All the World's Aircraft. Jane's Information Group. 6 February 2013.

- ↑ http://www.defenseworld.net/news/22128/US_Pressured_Indonesia_to_Abandon_Su_35_Fighter_Jet_Contract_with_Russia

Bibliography

- "Sukhoi fighter updates make debut appearance". Flight International. London: Reed Businees Information. 159 (4771): 20. 13–19 March 2001. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Andrews, Thomas (Spring 2003). "Su-27/30 family: 'Flanker' in the 21st Century". International Air Power Review. 8. Norwalk, Connecticut: AIRtime Publishing. ISBN 1-880588-54-4.

- Archibald, David (2016). "Resolving the F-35 Nightmare". Defense & Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy. Alexandria, Virginia: International Strategic Studies Association. 44 (2): 12–14. ISSN 0277-4933.

- Barrie, Douglas (26 February – 4 March 1997). "Advanced Flanker future hinges on export". Flight International. London: Reed Businees Information. 151 (4563): 8. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017.

- ——— (1 September 2003). "Singular Demands". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: McGraw-Hill. 159 (9): 39. ISSN 0005-2175.

- Butowski, Piotr (Summer 2004). "Halfway to PAK FA". Interavia Business & Technology. Geneva: Aerospace Media Publishing (676): 38–41. ISSN 1423-3215. Retrieved 19 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research. (Subscription required (help)).

- ——— (22 September 2007). "Wraps come off new Russian fighters". Interavia Business & Technology. Geneva: Aerospace Media Publishing (689): 34–36. ISSN 1423-3215. Retrieved 19 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research. (Subscription required (help)).

- Fink, Donald (6 December 1993). "New Su-35 Boasts Greater Agility". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: McGraw-Hill. 139 (23): 44–46. ISSN 0005-2175.

- Fiszer, Michal (August 2004). "Red Fighters Revised". Journal of Electronic Defense. Gainesville, Florida: Association of Old Crows. 27 (8): 43–44, 46–53. ISSN 0192-429X.

- Fomin, Andrey (May 2008). "Su-35 Has Flown!" (PDF). Take-Off. Moscow: Aeromedia Publishing: 24–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ——— (July 2012). "Su-35S in trials" (PDF). Take-Off. Moscow: Aeromedia Publishing: 16–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ——— (July 2014). "Su-35S Being Fielded With Success" (PDF). Take-Off. Moscow: Aeromedia Publishing: 36–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2017.

- Gethin, Howard (9–15 September 1998). "Sukhoi flies latest Su-37 demonstrator". Flight International. London: Reed Business Information. 154 (4642): 32. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Gill, Bates; Kim, Taeho (1995). China's Arms Acquisitions from Abroad: A Quest for 'Superb and Secret Weapons'. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829196-1.

- Gordon, Yefim (2007). Sukhoi Su-27. Famous Russian Aircraft. Hinckley, UK: Midlands Publishing. ISBN 1-85780-247-0.

- Joo, Seung-Ho; Kwak, Tae-Hwan Kwak (2001). Korea in the 21st Century. Hauppauge, New York: Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56072-990-7.

- Komarov, Alexey (4 February 2002). "Brazil Inks Fighter and Launcher Pacts with Russia and Ukraine". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: McGraw-Hill. 156 (5): 61. ISSN 0005-2175.

- Kopp, Carlo (March 2010). "Sukhoi's Su-35S – not your father's Flanker". Defence Today. Amberley, Queensland: Strike Publications: 8–10. ISSN 1447-0446.

- Mader, Georg (March 2007). "Los FLANKERs del Presidente". Military Technology. Bonn: Monch Publications. 31 (3): 102–104. ISSN 0722-3226.

- Novichkov, Nicolay (26 August 1996). "Sukhoi Set to Exploit Thrust Vector Control". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: McGraw-Hill. 145 (9): 52. ISSN 0005-2175.

- Pyadushkin, Maxim (13 December 2010). "Russian Revival". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: McGraw-Hill. 172 (45): 28. ISSN 0005-2175.

- ———; Perrett, Bradley (27 October 2014). "Back for More". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: Penton Media. 176 (38): 18–19. ISSN 0005-2175.

- Rivers, Brendan (February 2005). "Brazil Delays Fighter Program Again". Journal of Electronic Defense. Gainesville, Florida: Association of Old Crows. 28 (2): 18. ISSN 0192-429X.

- Sherman, Kenneth B. (1 September 2001). "US to ROK: "Buy American"". Journal of Electronic Defense. Gainesville, Florida: Association of Old Crows. 24 (9): 22. ISSN 0192-429X. Retrieved 22 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research. (Subscription required (help)).

- Sweetman, Bill (April 2004). "Russian stealth research revealed". Journal of Electronic Defense. Gainesville, Florida: Association of Old Crows. 27 (1): 26–27. ISSN 0192-429X. Retrieved 22 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research. (Subscription required (help)).

- ——— (24 June 2013). "Tight Corners". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: Penton Media. 175 (21): 33. ISSN 0005-2175. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ——— (19 August 2013). "New Moves". Aviation Week & Space Technology. New York: Penton Media. 175 (28): 43–44. ISSN 0005-2175. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Velovich, Alexander (8–14 May 1996). "Thrust-vectoring Sukhoi Su-35 flies". Flight International. London: Reed Business Publishing. 149 (4522): 16. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Williams, Mel, ed. (2002). "Sukhoi 'Super Flankers'". Superfighters: The Next Generation of Combat Aircraft. Norwalk, Connecticut: AIRtime Publishing. ISBN 1-880588-53-6.

- Zhao, Suisheng (2004). Chinese Foreign Policy: Pragmatism and Strategic Behavior. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1284-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sukhoi Su-35. |

- Official Sukhoi Su-35 webpages at Sukhoi and KnAAPO

- Sukhoi Su-35 Multifunctional fighter aircraft at AirRecognition.com

- Su-27M and Su-35BM webpages at GlobalSecurity.org