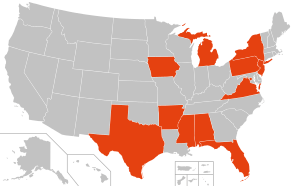

Solomon–Lautenberg amendment

Note: Virginia suspends driver's licenses for all drugs

except cannabis.

The Solomon–Lautenberg amendment is a U.S. federal law enacted in 1990, encouraging states to suspend the driver's license of anyone who commits a drug offense. A number of states passed laws in the early 1990s seeking to comply with the amendment, in order to avoid a penalty of reduced federal highway funds. These laws imposed mandatory driver's license suspensions of at least six months for persons committing a drug offense, regardless of whether any motor vehicle was involved. Although the amendment does contain a provision for states to opt out (without penalty), 10 states still had such laws in effect as of 2018.

Overview

The Solomon–Lautenberg amendment is named after its chief sponsors, Rep. Jerry Solomon (R–NY) and Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D–NJ).[1] It was signed into law on November 5, 1990, as part of the 1991 Department of Transportation and Related Agencies Appropriations Act.[1] The amendment urged states to impose a minimum six month driver's license suspension for any persons committing a drug offense, even for offenses unrelated to driving.[2] These suspensions were stipulated to apply to all illegal drugs (in any amounts), including the simple possession of cannabis.[3] States that took no action faced a 5% cut in federal highway funds by October 1993, and a 10% cut by October 1995.[1] As a result, many states passed so-called "Smoke a joint, lose your license" laws.[4]

For states that did not wish to implement such laws, however, the amendment did contain an opt-out provision, in which states would still be able to receive highway funds. To do so, state legislatures must vote specifically against implementing these suspensions, which a state's governor must also then approve.[1] The resolution is then sent to the Federal Highway Administration, which certifies that a state has properly opted out.[3] The process can take up to two years to complete.[3] In regards to the reasoning for this, an official in the Bush administration explained: "This forces the states to be accountable. We're not going to force you, but if you don't want to do it, you'll have to be public about it."[1]

The Solomon–Lautenberg amendment was criticized at the time by groups such as the National Governors Association and the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, but received little attention leading up to the bill's passage.[1] Speaking in support of his amendment, Rep. Jerry Solomon stated:[5]

Yes, we should do everything possible to interdict drugs coming into the country. Yes, we should provide adequate funds to treat addicts. And yes, we should jail – and in some cases even execute – those involved in the sale of drugs in this country. ... But let's not kid ourselves. That is not enough. ... Taking away driver's licenses in an automobile-oriented society will show that we are serious.

Complying states

As of 2018, the following jurisdictions still suspend driver's licenses for non-driving drug offenses: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia.[6] An estimated 191,000 licenses were suspended for non-driving drug offenses in the year 2016, according to a report by the Prison Policy Initiative.[6]

Jurisdictions that have opted out since 2009 include: Wisconsin (2009), Oklahoma (2010), Indiana (2014), Delaware (2014) Georgia (2015), Massachusetts (2016), Ohio (2016),[6] the District of Columbia (2017),[7] Utah (2018),[8] and Iowa (2018).[9] Additionally, Virginia passed opt-out legislation in 2017, but only as it pertains to the possession of cannabis.[10]

Criticisms

"Smoke a joint, lose your license" laws have been criticized for a variety of reasons, including the fact that the punishment often has nothing to do with the crime. The severity of punishment is also considered to be excessive, due to the life-altering impacts that losing one's license can cause. Loss of driving privileges can lead to loss of employment, which a New Jersey study showed happened in 42% of suspension cases.[11] In 45% of these cases, individuals were not able to find another job.[11]

Many who lose their license also continue to drive, a number PPI estimates to be as high as a 75%.[6] Drivers will then face even more severe punishments if caught, which further ties up police and other government resources.[6]

Critics have also noted the severe impact on minorities and low-income communities that these suspensions can cause. In New Jersey, 16% of the state population is considered low income, while 50% of people with suspended licenses are classified as such.[6] These individuals are then burdened by reinstatement fees that must be paid (up to $275 in Alabama), plus court fines and other fees.[6] Car insurance rates can also rise, even for suspensions that had nothing to do with driving.[3]

Efforts to repeal

In 2017, Rep. Beto O'Rourke (D–TX) introduced the Better Drive Act, seeking to repeal the Solomon–Lautenberg amendment.[12][13] To coincide with the bill's introduction, more than 30 advocacy groups signed a letter calling for the amendment's repeal.[11] Among the signatories of the letter was the NAACP, along with other civil rights, criminal justice reform, and addiction recovery organizations.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "States Are Pressed to Suspend Driver Licenses of Drug Users". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 16, 1990. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ↑ Beitsch, Rebecca (January 31, 2017). "States Reconsider Driver's License Suspensions for People With Drug Convictions". Stateline. The Pew Charitable Trusts. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Reefer sanity: States abandon driver's license suspensions for drug offenses". The Clemency Report. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ↑ Ingram, Carl (December 1, 1994). "'Smoke a Joint, Lose License' Law in Effect". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ↑ Mock, Brentin (January 18, 2018). "Why Is Pennsylvania Still Suspending Driver's Licenses for Drug Offenses?". CityLab. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Aiken, Joshua (December 12, 2016), "Reinstating Common Sense: How driver's license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving are falling out of favor", Prison Policy Initiative, retrieved January 26, 2018

- ↑ Kajstura, Aleks (March 23, 2018). "DC ends driver's license suspensions for unrelated drug offenses". Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ Davis, Molly (March 15, 2018). "Driver Licenses to No Longer Be Suspended for Drug Users". Libertas Institute. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ↑ Wolfe, Mary (June 12, 2018). "New laws will ease some driving restrictions". Clinton Herald. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ↑ Freedman, Emmy (November 7, 2017). "Law Removing Mandatory License Suspension with Marijuana Charge Goes into Effect". nbc29.com. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Driver's License Suspension Coalition Letter" (PDF). Drug Policy Alliance. April 6, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- 1 2 "U.S. Representative Beto O'Rourke Leads Bipartisan Bill that Repeals Federal Transportation Law Requiring States to Suspend Driver's Licenses for Drug Offenses". Drug Policy Alliance. April 5, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ↑ O'Rourke, Beto (April 5, 2017). "The Better Drive Act". Medium. Retrieved January 27, 2018.