Sigilmassasaurus

| Sigilmassasaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

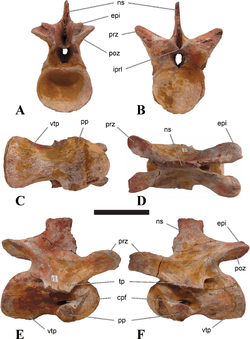

| Middle neck vertebra, specimen CMN 50791 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Spinosauridae |

| Tribe: | †Spinosaurini |

| Genus: | †Sigilmassasaurus Russell, 1996 |

| Species: | †S. brevicollis |

| Binomial name | |

| Sigilmassasaurus brevicollis Russell, 1996 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Sigilmassasaurus (/siːdʒɪlˌmɑːsəˈsɔːrəs/ see-jil-MAH-sə-SOR-əs; "Sijilmassa lizard") is a genus of tetanuran theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 100 to 94 million years ago during the middle of the Cretaceous Period in what is now northern Africa. Sigilmassasaurus was a moderately-built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore, like most other theropods.

Discovery and naming

Fossils of this dinosaur were recovered at the Kem Kem Formation in the Tafilalt Oasis region of Morocco, near the site of the ancient city of Sijilmassa, for which it was named. Canadian paleontologist Dale Russell named Sigilmassasaurus in 1996, from the ancient city and the Greek word sauros ("lizard"). A single species was named, S. brevicollis, which is derived from the Latin brevis ("short") and collum ("neck"), because the neck vertebrae are very short from front to back.[1]

Sigilmassasaurus comes from red sandstone sediments in southern Morocco, which are known by various names, including the Grès rouges infracénomaniens, Continental Red Beds, and lower Kem Kem Beds. These rocks date back to the Cenomanian, the earliest stage of the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 100 to 94 million years ago.[2]

Disputed validity

The holotype, or original specimen, of S. brevicollis, CMN 41857, is a single posterior neck vertebra, although Russell referred about fifteen other vertebrae found in the same formation to the species. Other material had been found in Egypt, and was referred to by Ernst Stromer as "Spinosaurus B".[3] Russell in 1996 considered this Egyptian specimen, IPHG 1922 X45, to belong to Sigilmassasaurus or a closely related animal, naming it as a Sigilmassasaurus sp. A second Sigilmassasaurus sp. was by him based on specimen CMN 41629, an anterior dorsal vertebra. "Spinosaurus B" would be intermediate in build between this latter Sigilmassasaurus sp. and S. brevicollis. Russell created the family Sigilmassasauridae for these animals.[1] The neck vertebrae of these dinosaurs are wider from side to side, about 50%, than they are long from front to back. Whether the neck as a whole was particularly short, is unknown: the holotype vertebra is a cervicodorsal, from the transition between the neck and the back, which would not be long anyway. The exact position of Sigilmassasaurus within the theropod family tree is unknown, but it belongs somewhere inside the theropod subgroup known as Tetanurae and most likely was a member of the family Spinosauridae.[4]

The validity of Sigilmassaurus, however, did not go unchallenged shortly after it was named. In 1996, Paul Sereno and colleagues described a Carcharodontosaurus skull (SGM-Din-1) from Morocco, as well as a neck vertebra (SGM-Din-3) which resembled that of "Spinosaurus B," which they therefore synonymized with Carcharodontosaurus.[5] A later in 1998 study went further, calling Sigilmassasaurus itself a junior synonym of Carcharodontosaurus.[6]

In 2005, however, Fernando Novas and colleagues found that SGM-Din-3, which was used to synonymize Carcharodontosaurus and "Spinosaurus B" was not actually associated with SGM-Din-1, the Carcharodontosaurus skull described in 1996, and shows clear differences with the holotype of Carcharodontosaurus. Other features of "Spinosaurus B" also clearly differ from Carcharodontosaurus, lending support to the notion that it (and therefore Sigilmassasaurus) is a separate taxon. The same study claimed that the tail vertebrae by Russell assigned to the species were in fact those of iguanodonts.[7] A study in 2013 confirmed that Sigilmassasaurus was valid and an indeterminate member of the Tetanurae.[8]

In 2014, Nizar Ibrahim and colleagues referred the specimens of Sigilmassasaurus to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, together with "Spinosaurus B" as the neotype, and Spinosaurus maroccanus was considered as a nomen dubium following the conclusions of the other papers.[9][10][11] In a 2015 re-description of Sigilmassasaurus by Serjoscha Evers and his team, it was considered a valid genus, belonging to Spinosauridae. This re-description also proposed Spinosaurus maroccanus as a junior synonym of Sigilmassaurus, and rejected the proposal of a Spinosaurus aegyptiacus neotype.[4]

A study by Thomas Arden and colleagues in 2018 concluded Sigilmassasaurus was a valid genus and formed a tribe with Spinosaurus termed Spinosaurini. The largest specimen of Spinosaurus cf. aegyptiacus, MSNM V4047, was tentatively assinged to S. brevicollis. On the basis of vertebrae, the researchers suggested that Sigilmassasaurus may have grown larger than Spinosaurus. Although in the absence of associated material, it is difficult to be certain what material belongs to which genus.[12]

Paleobiology

Diet and Feeding

On the bottoms of its cervical vertebrae, Sigilmassasaurus bore a series of highly rugged bony structures. These were suggested by Evers and colleagues as being possible evidence for substantial neck musculature, since the attachment sites of muscles and ligaments are often indicated by scarring on the bone surface. The neck muscles inferred from Sigilmassasaurus in particular would have enabled it to rapidly snatch fish out of the water, as indicated by the use of similarly-placed musculature in modern birds and crocodilians.[4] This has also been proposed for the related genus Irritator, on account of the prominent sagittal crest running towards the back of its head.[13] However, Evers and colleagues noted that a more thorough biomechanical analysis is required for confirmation of this condition in Sigilmassasaurus.[4]

Paleoecology

Several large theropods (more than one tonne) are known from the Cenomanian of northern Africa, raising questions about how such animals would have coexisted. Species of Spinosaurus, the largest known theropod, has been found in both Morocco and Egypt, as has the huge Carcharodontosaurus. Two smaller theropods, Deltadromeus and Bahariasaurus, have also been found in Morocco and Egypt, respectively, and may be closely related or possibly the same genus. Sigilmassasaurus, from Morocco, and "Spinosaurus B", from Egypt, represent a fourth type of large predator. This situation resembles that in the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of North America, which boasts up to five theropod genera over one tonne in weight, as well as several smaller genera.[14][15] Differences in head shape and body size among the large North African theropods may have been enough to allow niche partitioning as seen among the many different predator species found today in the African savanna.[16]

References

- 1 2 Russell, D.A. (1996). "Isolated Dinosaur bones from the Middle Cretaceous of the Tafilalt, Morocco". Bulletin - Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle Section C: Sciences de la Terre. 18: 349–402.

- ↑ Sereno, PC; Dutheil, DB; Iarochene, M; Larsson, HCE; Lyon, GH; Magwene, PM; Sidor, CA; Varricchio, DJ; Wilson, JA (1996). "Predatory dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous faunal differentiation". Science. 272: 986–991. Bibcode:1996Sci...272..986S. doi:10.1126/science.272.5264.986. PMID 8662584.

- ↑ Stromer, E. (1934). "Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltier-Reste der Baharije-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). 13. Dinosauria". Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung, Neue Folge (in German). 22: 1–79.

- 1 2 3 4 Evers, S. W.; Rauhut, O. W. M.; Milner, A. C.; McFeeters, B.; Allain, R. (2015). "A reappraisal of the morphology and systematic position of the theropod dinosaur Sigilmassasaurus from the "middle" Cretaceous of Morocco". PeerJ. 3: e1323. doi:10.7717/peerj.1323. PMC 4614847. PMID 26500829.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C.; Dutheil, Didier B.; Iarochene, M.; Larsson, Hans C. E.; Lyon, Gabrielle H.; Magwene, Paul M.; Sidor, Christian A.; Varricchio, David J.; Wilson, Jeffrey A. (1996). "Predatory Dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous Faunal Differentiation". Science. 272 (5264): 986–991. doi:10.1126/science.272.5264.986. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 8662584.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C.; Beck, Allison L.; Dutheil, Didier B.; Gado, Boubacar; Larsson, Hans C. E.; Lyon, Gabrielle H.; Marcot, Jonathan D.; Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Sadleir, Rudyard W. (1998). "A Long-Snouted Predatory Dinosaur from Africa and the Evolution of Spinosaurids". Science. 282 (5392): 1298–1302. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1298. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9812890.

- ↑ Novas, Fernando; de Valais, Silvina; Vickers Rich, Patricia; Rich, Tom (2005). "A large Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia, Argentina, and the evolution of carcharodontosaurids". Die Naturwissenschaften. 92: 226–30. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0623-3.

- ↑ McFeeters, Bradley; Ryan, Michael J.; Hinic-Frlog, Sanja; Schröder-Adams, Claudia (2013). "A reevaluation of Sigilmassasaurus brevicollis (Dinosauria) from the Cretaceous of Morocco". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 50: 636–649. Bibcode:2013CaJES..50..636M. doi:10.1139/cjes-2012-0129.

- ↑ dal Sasso, C.; Maganuco, S.; Buffetaut, E.; Mendez, M.A. (2005). "New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 888–896. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0888:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Fabri, Matteo; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir; Myhrvold, Nathan; Lurino, Dawid A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–6. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1613I. doi:10.1126/science.1258750. PMID 25213375. Supplementary Information

- ↑ Sereno, P.C.; Beck, A.L.; Dutheil, D.B.; Gado, B.; Larsson, H.C.E.; Lyon, G.H.; Marcot, J.D.; Rauhut, O.W.M.; Sadleir, R.W.; Sidor, C.A.; Varricchio, D.D.; Wilson, G.P; Wilson, J.A. (1998). "A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids". Science. 282 (5392): 1298–1302. Bibcode:1998Sci...282.1298S. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1298. PMID 9812890.

- ↑ Arden, T.M.S.; Klein, C.G.; Zouhri, S.; Longrich, N.R. (2018). "Aquatic adaptation in the skull of carnivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) and the evolution of aquatic habits in Spinosaurus". Cretaceous Research. In Press. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.06.013.

- ↑ Sues, H. D.; Frey, E.; Martill, D. M.; Scott, D. M. (2002). "Irritator challengeri, a spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 535–547. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ M Henderson, Donald (1998). "Skull and tooth morphology as indicators of niche partitioning in sympatric Morrison Formation theropods". Gaia. 15.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas; E. Molnar, Ralph; Currie, Philip (2004), "Basal Tetanurae", The Dinosauria: Second Edition, pp. 71–110

- ↑ Farlow, James O.; Planka, Eric R. (2002). "Body Size Overlap, Habitat Partitioning and Living Space Requirements of Terrestrial Vertebrate Predators: Implications for the Paleoecology of Large Theropod Dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1080/0891296031000154687. ISSN 0891-2963.

.jpg)

.png)