Shang Yang

| Shang Yang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

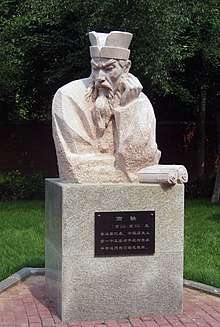

Statue of pivotal reformer Shang Yang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 商鞅 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

|

Early figures |

|

Founding figures |

|

Later figures |

Shang Yang (/ʃɑːŋ/;[1] Chinese: 商鞅; pinyin: Shāng Yāng), or Wei Yang Gongsun[2] (Chinese: 衞鞅; pinyin: Wèi Yāng; c. 390 – 338 BCE). Born in Wey, Zhou Kingdom,[2] he was a statesman and reformer of the State of Qin during the Warring States period of ancient China. His policies laid the administrative and political foundations that would enable Qin to conquer all of China, uniting the country for the first time and ushering in the Qin dynasty. He and his followers contributed to the Book of Lord Shang, a foundational work for the development of Chinese Legalism.[3]

Biography

With the support of Duke Xiao of Qin, Shang Yang left his lowly position in Wei (to whose ruling family he had been born, but had yet to obtain a high position in)[4] to become the chief adviser in Qin. There his numerous reforms transformed the peripheral Qin state into a militarily powerful and strongly centralized kingdom. Changes to the state's legal system (which were said to have been built upon Li Kui's Canon of Laws) propelled the Qin to prosperity. Enhancing the administration through an emphasis on meritocracy, his policies weakened the power of the feudal lords.

Mark Edward Lewis once identified his reorganization of the military as responsible for the orderly plan of roads and fields throughout north China. This might be far fetched, but Gongsun was as much a military reformer as a legal one.[5] Gongsun oversaw the construction of Xiangyang.[6]

The Shang Yang school of thought was favoured by Emperor Wu of Han,[7] and John Keay mentions that Tang figure Du You was drawn to Shang Yang.[8]

Reforms

He is credited by Han Fei with the creation of two theories;

Believing in the rule of law and considering loyalty to the state above that of the family, Gongsun introduced two sets of changes to the State of Qin. The first, in 356 BCE, were:

- Li Kui's Book of Law was implemented, with the important addition of a rule providing punishment equal to that of the perpetrator for those aware of a crime but failing to inform the government. He codified reforms into enforceable laws.

- Assigning land to soldiers based upon their military successes and stripping nobility unwilling to fight of their land rights. The army was separated into twenty military ranks, based upon battlefield achievements.

- As manpower was short in Qin, Gongsun encouraged the cultivation of unsettled lands and wastelands and immigration, favouring agriculture over luxury commerce (though also paying more recognition to especially successful merchants).

Gongsun introduced his second set of changes in 350 BCE, which included a new standardized system of land allocation and reforms to taxation.

The vast majority of Gongsun's reforms were taken from policies instituted elsewhere, such as from Wu Qi of the State of Chu; however, Gongsuns's reforms were more thorough and extreme than those of other states. Under Gongsun's tenure, Qin quickly caught up with and surpassed the reforms of other states.

Domestic policies

Gongsun introduced land reforms, privatized land, rewarded farmers who exceeded harvest quotas, enslaved farmers who failed to meet quotas, and used enslaved subjects as (state-owned) rewards for those who met government policies.

As manpower was short in Qin relative to the other states at the time, Gongsun enacted policies to increase its manpower. As Qin peasants were recruited into the military, he encouraged active migration of peasants from other states into Qin as a replacement workforce; this policy simultaneously increased the manpower of Qin and weakened the manpower of Qin's rivals. Gongsun made laws forcing citizens to marry at a young age and passed tax laws to encourage raising multiple children. He also enacted policies to free convicts who worked in opening wastelands for agriculture.

Gongsun partly abolished primogeniture (depending on the performance of the son) and created a double tax on households that had more than one son living in the household, to break up large clans into nuclear families.

Gongsun moved the capital to reduce the influence of nobles on the administration.

Gongsun's death

Deeply despised by the Qin nobility,[9] Gongsun could not survive Duke Xiao of Qin's death. The next ruler, King Huiwen, ordered the nine familial exterminations against Gongsun and his family, on the grounds of fomenting rebellion. Yang had previously humiliated the new duke "by causing him to be punished for an offense as though he were an ordinary citizen."[10] Yang went into hiding and tried to stay at an inn. The innkeeper refused because it was against Yang's laws to admit a guest without proper identification, a law Yang himself had implemented.

Yang was executed by jūliè (車裂, dismemberment by being fastened to five chariots, cattle or horses and being torn to pieces);[11][12] his whole family was also executed.[9] Despite his death, King Huiwen kept the reforms enacted by Gongsun. A number of alternate versions of Gongsun's death have survived. According to Sima Qian in his Records of the Grand Historian, Gongsun fled to his fiefdom, where he raised a rebel army but was killed in battle. After the battle, King Hui of Qin had Yang's corpse torn apart by chariots as a warning to others.

Following the execution of Gongsun, King Huiwen turned away from the central valley south to conquer Sichuan (Shu and Ba) in what Steven Sage calls a "visionary reorientation of thinking" toward material interests in Qin's bid for universal rule.[13]

In fiction and popular culture

- Portrayed by Shi Jingming in The Legend of Mi Yue (2015)

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Shang". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- 1 2 Antonio S. Cua (ed.), 2003, p. 362, Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy

- ↑ Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), 1.1 Major Legalist Texts, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/chinese-legalism/

- ↑ pg 79 of Classical China

- ↑ Paul R. Goldin, Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism. p. 18

- ↑ John Man 2008. p. 51. Terra Cotta Army.

- ↑ Creel 1970, What Is Taoism?, 115

- ↑ Arthur F. Wright 1960. p. 99. The Confucian Persuasion.

- 1 2 商君列传 (vol. 68), Records of the Grand Historian, Sima Qian

- ↑ pg 80 of Classical China, ed. William H. McNeill and Jean W. Sedlar, Oxford University Press, 1970. LCCN: 68-8409

- ↑ 和氏, Han Feizi, Han Fei

- ↑ 东周列国志, 蔡元放

- ↑ Steven F. Sage 1992. p.116. Ancient Sichuan and the Unification of China. https://books.google.com/books?id=VDIrG7h_VuQC&pg=PA116

References

- Zhang, Guohua, "Shang Yang". Encyclopedia of China (Law Edition), 1st ed.

- Xie, Qingkui, "Shang Yang". Encyclopedia of China (Political Science Edition), 1st ed.

- 国史概要 (第二版) ISBN 7-309-02481-8

- 戰國策 (Zhan Guo Ce), 秦第一

Further reading

- Li Yu-ning, ShangYang's Reforms (M.E. Sharpe Inc., 1977).

External links

- Hansen, Chad. "Lord Shang (died 338 BC)". Chad Hansen's Chinese Philosophy Pages.

- Duyvendak, J. J. L. "商君書 - Shang Jun Shu". Chinese Text Project.

- "秦一". Chinese Text Project.

- Works by Yang Shang at Project Gutenberg