Xu Guangqi

| Xu Guangqi 徐光啓 Servant of God | |

|---|---|

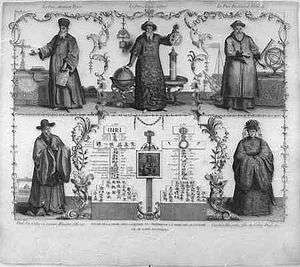

Portrait of Xu Guangqi | |

| Born |

April 24, 1562 Shanghai, Songjiang, Southern Zhili, China[1] |

| Died |

November 8, 1633 (aged 71)[2] Beijing, Shuntian, Northern Zhili, China |

| Resting place | Guangqi Park, Xujiahui, Xuhui District, Shanghai, China |

| Residence | Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Other names | Paul Xu |

| Citizenship | Ming Dynasty |

| Education | Jinshi Degree (1604)[3] |

| Occupation | scholar-official (Minister of Rites and Grand Secretary) |

| Employer | Ming imperial court (under the Wanli, Taichang, Tianqi and Chongzhen Emperors) |

| Known for |

Three Pillars of Chinese Catholicism Chinese translation of Euclid's Elements Chongzhen calendar Complete Treatise on Agriculture |

| Home town | Shanghai |

| Spouse(s) | Wu[4] |

| Children | Xu Ji (徐驥) |

| Parent(s) | Xu Sicheng (徐思誠), father |

| Relatives |

Candida Xu (granddaughter)[5] (Xu Zhun)[6] (Xu Maheux)[6] |

| Xu Guangqi | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 徐光啓 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 徐光启 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 子先 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 玄扈 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 保祿 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 保禄 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Paulus | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Xu Guangqi or Hsü Kuang-ch'i (April 24, 1562 – November 8, 1633), also known by his baptismal name Paul, was a Chinese scholar-bureaucrat, Catholic convert, agricultural scientist, astronomer, and mathematician under the Ming dynasty.[7] Xu was a colleague and collaborator of the Italian Jesuits Matteo Ricci and Sabatino de Ursis and assisted their translation of several classic Western texts into Chinese, including part of Euclid's Elements. He was also the author of the Nong Zheng Quan Shu, a treatise on agriculture. He was one of the "Three Pillars of Chinese Catholicism". His current title is Servant of God.[8] On April 15, 2011, Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi announced the beatification of Xu Guangqi.[9][10]

Name

Xu Guangqi is the pinyin romanization of the Standard Chinese pronunciation of Xu's Chinese name. It was formerly written Hsü Kuang-ch‘i using the Wade–Giles system. His courtesy name was Zixian and his penname was Xuanhu. In the Jesuits' records, it is the last which is used as his Chinese name, in the form "Siù Hsven Hú".[11]

At his conversion, he adopted the baptismal name Paul (Latin: Paulus). In Chinese, its transcription is employed as a kind of courtesy name (i.e., Xu Baolu) and the Jesuits sometimes referred to him as "Siù Pao Lò"[11] or Ciù Paulus.[12] More often, however, they describe him as "Doctor Paul" (Latin: Doctor Paulus;[13][11] Portuguese: Doutor Paulo),[14] "Our Paul" (Latin: noster Paulus), or "Paul Siu"[15] or "Ciu".[12][lower-alpha 1]

Life

Xu Guangqi was born in Shanghai in Southern Zhili's Songjiang Prefecture on April 24, 1562,[1] under China's Ming dynasty. At the time, Shanghai was merely a small walled county seat in the old quarter around the present city's Yu Garden. His family, including an older and younger sister, lived in the Taiqing Quarter at the south end of the town. Guangqi's branch of the Xus were not related to those who had passed the imperial examinations and joined Shanghai's local gentry.[17] His father Xu Sicheng (died c. 1607)[18] had been orphaned at age 5 and seen most of his inheritance lost to "Japanese" pirate raids and insolvent friends in the 1550s.[17]

At the time of Guangqi's birth, his father worked twenty mu (1¼ ha)[19] or less south of the city wall.[20] About half of this would have been used to feed the family,[21] with the rest used to supplement his income from small-scale trading.[17] By the time Guangqi was 6, the family had saved enough to send him to a local school, where a later hagiographer records him piously upbraiding his classmates when they spoke of wanting to use their education for wealth or mystical power. Instead, he supposedly advised, "None of these things is worth doing. If you want to talk about the sort of person you want to become, then it should be to establish yourself and to follow the Way. Bring order to the state and the people. Revere the orthodox and expose the heterodox. Don't waste the chance to be someone who matters in this world."[20] From 1569 to 1573, the family sent Guangqi to the school at the Buddhist monastery at Longhua.[1] It is not recorded, but this school was probably a separate secular and fee-based institution for families too poor to hire private tutors for their sons.[20]

His mother died on May 8, 1592, and he undertook the ritual mourning period in her honor.[22] His whereabouts over the next few years are uncertain but he seems to have failed the provincial exam at Beijing in 1594, after the mourning period was over.[22]

In 1596, he moved to Xunzhou (now Guiping) in Guangxi to assist its prefect Zhao Fengyu, a Shanghai native who had passed the juren exams in 1555.[22] The next year, he traveled to Beijing in the spring and passed its provincial exam, becoming a juren.[22] He seems to have stayed there for the imperial exam the next year, but failed to pass. He then returned to Shanghai around April, turning his attention to the study of military and agricultural subjects.[22] The next year he studied under Cheng Jiasui.[22]

He first met Matteo Ricci, the Italian Jesuit, in Nanjing in March or April 1600.[22] He collaborated with Ricci in translating several classic Western texts—most notably the first part of Euclid's Elements—into Chinese, as well as several Chinese Confucian texts into Latin.[23] Ricci's influence led to Xu being baptized as a Roman Catholic in 1603. His descendants remained Catholics or Protestants into the 21st century..

From 1607 until 1610, Xu was forced to retire from public office and returned to his home in Shanghai. It was during this time that he experimented with Western-style irrigation methods.[24] He also experimented with the cultivation of sweet potatoes, cotton, and the nu zhen tree.[24] He was called once more to serve the Chinese bureaucracy, where he rose to a high rank and became known late in his career simply as "The Minister".[23] Yet he continued to experiment and learn of new agricultural practices while he served his office, promoting the use of wet-rice in the Northeast China.[24] From 1613 until 1620 he often visited Tianjin, where he helped organize self-sufficient military settlements (tun tian).[24]

In 1629, memorials by Xu and his fellow convert Leo Li successfully moved the court to permit the Portuguese captain Gonçalo Teixeira-Correa to bring 10 artillery pieces and 4 "excellent bombards" across China to the capital to demonstrate the effectiveness of Western artillery.[13] An earlier demonstration in 1623 had gone disastrously, with an exploding cannon killing one Portuguese artillerist and three Chinese observers, but on this occasion the pieces were accepted and directed to Dengzhou (now Penglai) in Shandong.[25] The Christian convert Ignatius Sun, a protégé of Xu's, was governor there and had also been a strong advocate of modernizing China's military.[26] Together with Captain Teixeira and his translator João Rodrigues, Sun used the pieces to train his troops to oppose the ongoing Manchu invasion. However, Sun's lenient treatment of a 1632 mutiny under Kong Yude and Geng Zhongming permitted them to successfully capture Dengzhou, seize the artillery, and establish an independent power base that eventually joined the Manchus.[26] Xu's memorials for clemency were unsuccessful and Sun was court-martialed and executed.[15]

He held the positions of Minister of Rites (禮部尙書), overseeing government programs related to culture, education, and foreign affairs, and Deputy Senior Grand Secretary (內閣次輔), effectively a deputy premier for the imperial cabinet.

Johann Adam Schall von Bell stayed with Xu during his final illness in 1633 and oversaw the return of his body to his family in Shanghai.[27] There, it was publicly displayed at his villa until 1641, when it was buried "in a time of hardship".[15]

Legacy

Xu Guangqi's tomb remains the centerpiece of Shanghai's Guangqi Park on Nandan Road (南丹路), just south of Xujiahui Cathedral.

The 350th anniversary of his death in 1983 was celebrated very publicly, both with ceremonies in Shanghai and a laudatory article in the Beijing Review. The vocal Communist support for these memorials has been seen as signaling support for Deng Xiaoping's policies of opening up and modernizing China.[28] Most Chinese treatments of his life and legacy, however, focus upon his desire for scientific, technological, and political progress and its effect upon Chinese development, whereas western treatments nearly universally attach great importance to his Christian conversion and identity.[28]

Works

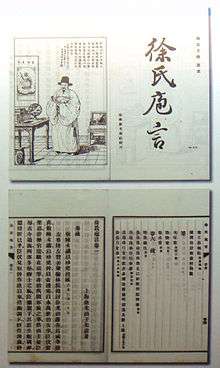

Military sciences

Xu Guangxi was especially worried about the ability of his country to defend itself, especially in the face of the threat of invasion from the Manchus. He wrote a book on military techniques and strategies entitled Cook Xu's Words in response to the criticisms he faced for daring discuss military matters in spite of being a mere scholar.[29] He frequently cited the Xunzi and Guanzi, and made use of rewards and punishments along the lines of the Legalists, at least in relief activities.[30]

Xu Guangqi put forward the concept of a "Rich Country and Strong Army" (富國強兵), which would be adopted by Japan for its modernization in the end of the 19th century, under the name Fukoku Kyohei.

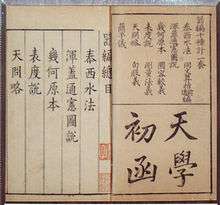

Mathematics

In 1607, Xu and Ricci translated the first parts of Euclid's Elements into Chinese, introducing his countrymen to new concepts in mathematics and Western logic. Chinese scholars credit Xu as having "started China's enlightenment".[23]

Astronomy

After followers of Xu and Ricci publicly predicted a solar eclipse in 1629, Xu was appointed by the Emperor as the leader of an effort to reform the Chinese calendar. The reform, which constituted the first major collaboration between scientists from Europe and from the Far East, was completed after his death.[23]

Agriculture

Xu Guangqi wrote the Nong Zheng Quan Shu (Complete Treatise on Agriculture), an outstanding agricultural treatise that followed in the tradition of those such as Wang Zhen (wrote the Wang Zhen Nong Shu of 1313 AD) and Jia Sixia (wrote the Chi Min Yao Shu of 535 AD).[31] Like Wang Zhen, Xu lived in troubled times, and was devoted as a patriot to aiding the rural farmers of China.[24] His main interests were in irrigation, fertilizers, famine relief, economic crops, and empirical observation with early notions of chemistry.[24] It was an enormous written work, some 700,000 written Chinese characters, making it 7 times as large as the work of both Jia Sixia and Wang Zhen.[32] Although its final draft was unfinished by Xu Guangqi by the time of his death in 1633, the famous Jiangnan scholar Chen Zilung assembled a group of scholars to edit the draft, publishing it in 1639.[32]

The topics covered by his book are as follows:[32]

- The Fundamentals of Agriculture (Nong Ben): quotations from the classics on the importance of encouraging agriculture

- Field System (Tian Zhi): land distribution, field management

- Agricultural Tasks (Nong Shi): clearing land, tilling; also a detailed exposition on settlement schemes

- Water Control (Shui Li): various methods of irrigation, types of irrigation equipment, and the last two chapters devoted to new Western-style irrigation equipment

- Illustrated Treatise on Agricultural Implements (Nong Chi Tu Pu): based largely on Wang Zhen's book of 1313 AD

- Horticulture (Shi Yi): vegetables and fruit

- Sericulture (Can Sang): silk production

- Further Textile Crops (Can Sang Guang Lei): cotton, hemp, etc.

- Silviculture (Chong Chi): forestry preservation

- Animal Husbandry (Mu Yang)

- Culinary Preparations (Zhi Zao)

- Famine Control (Huang Zheng): administrative measures, famine flora

Family

Xu's only son was John Xu[15] (t 徐驥, s 徐骥, Xú Jì),[4] whose daughter was Candida Xu (徐甘第大, Xú Gāndìdà; 1607–1680). A devout Christian, she was recognized as an important patron of Christianity in Jiangnan during the early Qing era. The Jesuit Philippe Couplet, who worked closely with her, composed her biography in Latin. This was published in French translation as A History of the Christian Lady of China, Candide Hiu (Histoire d'une Dame Chrétienne de la Chine, Candide Hiu) in 1688.[33] Her son was Basil Xu, who served as an official under the Qing.[15]

See also

- Xu Guangqi Memorial Hall

- Roman Catholicism in China

- Shanghainese people

- History of agriculture

- Xavier School in San Juan, Metro Manila, the Philippines

Notes

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Dudink (2001), p. 399

- ↑ Dudink & 2001 (409).

- ↑ Liam Matthew Brockey, Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724 (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 59.

- 1 2 Dudink (2001), p. 400

- ↑ Liam Matthew Brockey, Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724 (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 140.

- 1 2 Liam Matthew Brockney, Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724 (cambridge: The Belknap press of Harvard University Press , 2008),140.

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/HSU_KUANG-CH'I.html

- ↑ Roman Catholic Diocese of Shanghai: 徐光启列品案筹备进程

- ↑ "Church to beatify early China convert in Shanghai - ucanews.com". Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ↑ http://shanghaiist.com/2011/04/18/xu-guangqi-beatification.php

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blue (2001), p. 48

- 1 2 Blue (2001), p. 33

- 1 2 Blue (2001), p. 44

- ↑ Vasconcelos (2012), p. 163.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blue (2001), p. 45

- ↑ Blue (2001), p. 49

- 1 2 3 Brook (2001), p. 93

- ↑ Blue (2001), p. 35.

- ↑ Wilkinson (2000), p. 243.

- 1 2 3 Brook (2001), p. 94

- ↑ Clunas (1996), p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dudink (2001), p. 402

- 1 2 3 4 Stone (2007).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Needham (1984), p. 65.

- ↑ Chan (1976), p. 1147.

- 1 2 Fang (1944).

- ↑ Blue (2001), pp. 42–3.

- 1 2 Blue (2001), p. 19

- ↑ Xu Guangqi Memorial Hall permanent exhibit

- ↑ Smith (2009), p. 252.

- ↑ Needham (1984), pp. 64–5.

- 1 2 3 Needham (1984), p. 66.

- ↑ Mungello (1989), pp. 253–254.

Sources

- Blue, Gregory (2001), "Xu Guangqi in the West: Early Jesuit Sources and the Construction of an Identity", Statecraft & Intellectual Renewal in Late Ming China: The Cross-Cultural Synthesis of Xu Guangqi (1562–1633), Sinica Leidensia, Vol. 50, Leiden: Brill, pp. 19–71 .

- Brook, Timothy (2001), "Xu Guangqi in His Context: The World of the Shanghai Gentry", Statecraft & Intellectual Renewal in Late Ming China: The Cross-Cultural Synthesis of Xu Guangqi (1562–1633) .

- Chan, Albert (1976), "João Rodrígues", Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644, Vol. II: M–Z, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1145–47 .

- Clunas, Craig (1996), Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China, Envisioning Asia, London: Reaktion Books .

- Dudink, Adrianus Cornelis (2001), "Xu Guangqi's Career: An Annotated Chronology", Statecraft & Intellectual Renewal in Late Ming China .

- Wilkinson, Endymion Porter (2000), Chinese History: A Manual, Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard–Yenching Institute .

- Fang Zhaoying (1944), "Sun Yüan-hua", Eminent Chinese of the Ch‘ing Period (1644–1912), Vol. II: P–Z, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 686 .

- Mungello, David E. (1989), Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1219-0 .

- Needham, Joseph (1984), Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. VI: Biology and Biological Technology, Part 2: Agriculture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Smith, Joanna Handlin (2009), The Art of Doing Good: Charity in Late Ming China .

- Stone, Richard (2007), "Scientists Fete China's Supreme Polymath", Science, Vol. 318, p. 733 .

- Vasconcelos de Saldanha, António (2012), "The Last Imperial Honours: From Tomás Pereira to the Eulogium Europeorum Doctorum in 1711", In the Light and Shadow of an Emperor: Tomás Pereira, SJ (1645–1708), the Kangxi Emperor, and the Jesuit Mission in China, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 144–227 .

Further reading

- Needham, Joseph (1959). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; reprinted: Taipei: Caves Books, 1986. OCLC

- Zhao, Jikai, "Xu Guangqi". Encyclopedia of China (Economics Edition), 1st ed.

- Mei, Rongzhao, "Xue Guangqi". Encyclopedia of China (Mathematics Edition), 1st ed.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |