Secular state

A secular state is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion.[1] A secular state also claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of religion, and claims to avoid preferential treatment for a citizen from a particular religion/nonreligion over other religions/nonreligion. Secular states do not have a state religion (established religion) or equivalent, although the absence of a state religion does not necessarily mean that a state is fully secular.

Origin and practice

Secular states become secular either upon creation of the state (e.g. the United States of America), or upon secularization of the state (e.g. France or Nepal). Movements for laïcité in France and for the separation of church and state in the United States defined modern concepts of secularism. Historically, the process of secularizing states typically involves granting religious freedom, disestablishing state religions, stopping public funds being used for a religion, freeing the legal system from religious control, freeing up the education system, tolerating citizens who change religion or abstain from religion, and allowing political leadership to come to power regardless of their religious beliefs.[2]

In France and Spain for example, official holidays for the public administration seem to be Christian feast days whereas they have older pagan roots prior to christianism, Toussaint is pagan Halloween and Paques/Easter is pagan god Eostre celebration which english kept the name. Also any private school in France that contracts with Education Nationale gets the teachers salaried by the state, so most of Catholic school are in this case and they are the majority because of history but it's not an exclusive pass right and other religion or non religion school can contract this way.[3] In some European states where secularism confronts monoculturalist philanthropy, some of the main Christian sects and sects of other religions depend on the state for some of the financial resources for their religious charities.[4] It is common in corporate law and charity law to prohibit organized religion from using those funds to organize religious worship in a separate place of worship or for conversion; the religious body itself must provide the religious content, educated clergy and laypersons to exercise its own functions and may choose to devote part of their time to the separate charities. To that effect some of those charities establish secular organizations that manage part of or all of the donations from the main religion(s).

Religious and non-religious organizations can apply for equivalent funding from the government and receive subsidies based on either assessed social results where there is indirect religious state funding, or simply the number of beneficiaries of those organisations.[5] This resembles charitable choice in the United States. It is doubtful whether overt direct state funding of religions is in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights. Apparently this issue has not yet been decided at supranational level in ECtHR case law stemming from the rights in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which mandates non-discrimination in affording its co-listed basic social rights. Specifically, funding certain services would not accord with non-discriminatory state action.[6]

Many states that are nowadays secular in practice may have legal vestiges of an earlier established religion. Secularism also has various guises which may coincide with some degree of official religiosity. In the United Kingdom, the head of state is still required to take the Coronation Oath enacted in 1688, swearing to maintain the Protestant Reformed religion and to preserve the established Church of England.[7] The UK also maintains seats in the House of Lords for 26 senior clergymen of the Church of England, known as the Lords Spiritual.[8] The reverse progression can also occur, however; a state can go from a secular state to a religious state, as in the case of Iran where the secularized state of the Pahlavi dynasty was replaced by an Islamic Republic (list below). Nonetheless, the last 250 years has seen a trend towards secularism.[9][10][11]

List of self-described secular states by continent

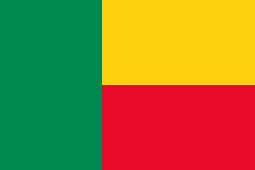

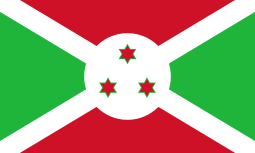

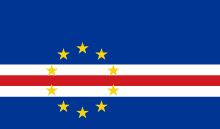

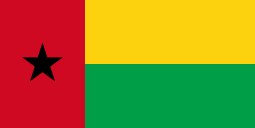

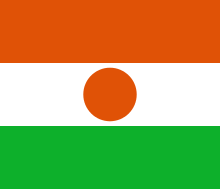

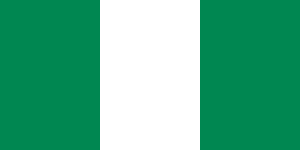

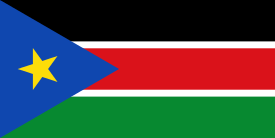

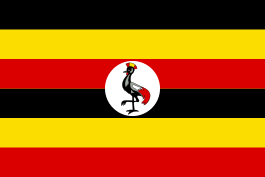

Africa

Asia

Europe

.svg.png)

1 Transcontinental country.

2 States with limited recognition.

3 In Belgium, Article 20 of the Constitution provides: No one can be obliged to contribute in any way whatsoever to the acts and ceremonies of a religion, nor to observe the days of rest.[72]

North America

- Article 77 of the Constitution of Honduras states: "It guarantees the free exercise of all religions and cults without precedence, provided they do not contravene the laws and public order. The ministers of different religions, may not hold public office or engage in any form of political propaganda, on grounds of religion or using as a means to that end of the religious beliefs of the people." [75][76]

- Article 130 of the Constitution of Mexico states that "Congress cannot enact laws establishing or prohibiting any religion."

Oceania

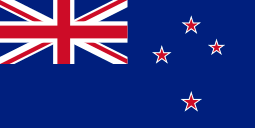

- Section 116 of the Constitution of Australia provides that "the Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.[77]

- Article 4 of the 2013 Constitution of Fiji explicitly provides that Fiji is a secular state. It guarantees religious liberty, while stating that "religious belief is personal", and that "religion and the State are separate."[78]

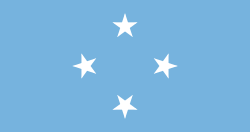

- Section 2 of Article IV of the Micronesian constitution provides that "no law may be passed respecting an establishment of religion or impairing the free exercise of religion, except that assistance may be provided to parochial schools for non-religious purposes."[79]

South America

Former secular states

.svg.png)

- Afghanistan became a secular state after the Saur Revolution but Islam became an official religion again in 1980.

.svg.png)

- Iran was a secular state until the Islamic Revolution of 1979, which overthrew the Shah.

.svg.png)

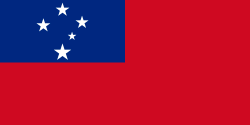

- In 2017, the Samoan legislative assembly approved an constitutional amendment that instituted Christianity as the state religion.[87]

Ambiguous states

- According to Section 2 of the Constitution of Argentina, "The Federal Government supports the Roman Catholic Apostolic religion" but it does not stipulate an official state religion, nor a separation of church and state. In practice, however, the country is mostly secular, and there is no kind of persecution of people of other religions; they are completely accepted and even encouraged in their activities.

- The constitution formally separates the church from the state; however, it recognizes the Armenian Apostolic Church as the national church.[88]

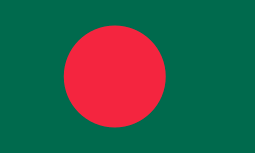

- There is a constitutional ambiguity that Bangladesh is both Islamic[89] and secular.[90] The Bangladesh high court rejected a proposal to turn all to Islamic feature.[91] However, on 28 March 2016, the court then issued a verdict which "upholds Islam as the religion of the State"[92] But the nation did not remove secularism from its constitution.[93] Secularism is still one of founding principles of Bangladesh.[94][95] There is also another Freedom of Religion law in Bangladesh that always existed.

- Article 26 of the El Salvadoran constitution recognizes the Catholic Church and gives it legal preference.[96][97]

- Claims to be secular, but the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland and the Finnish Orthodox Church have the right to collect church tax from their members in conjunction with government income tax. In addition to membership tax, businesses also contribute financially to the church through tax.

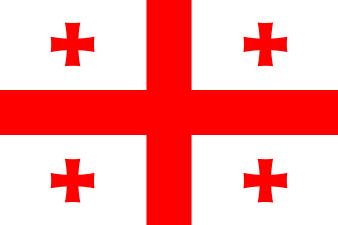

- Georgia gives distinct recognition to the Georgian Orthodox Church in Article 9 of the Constitution of Georgia[98] and through the Concordat of 2002.[99] However, the Constitution also guarantees "absolute freedom of belief and religion".[98]

- The first principle of Pancasila, the national ideology of Indonesia, refers to "belief in the one and only God" (in Indonesian: Ketuhanan yang Maha Esa). A number of different religions are practiced in the country.[100] The Constitution of Indonesia guarantees freedom of religion among Indonesians. However, the government only recognizes six official religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.[101][102] Other religious groups are called kepercayaan (Indonesian: faith), including several indigenous beliefs. Religious studies are compulsory for students from elementary school to high school. Places of worship are prevalent in schools and offices. A Minister of Religious Affairs is responsible for administering and managing government affairs related to religion.[103] If a secular state is defined as "supporting neither religion nor irreligion", then Indonesia is not a secular state, since irreligion is not allowed, even though not prosecuted. There is a preference for several official religions, which is represented in the government through the ministry of religion.

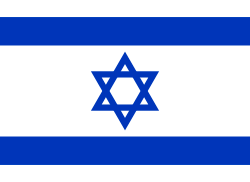

- When the idea of modern political Zionism was introduced by Theodor Herzl, his idea was that Israel would be a secular state which would not be influenced at all by religion. When David Ben-Gurion founded the state of Israel, he put religious parties in government next to secular Jews in the same governing coalition. Many secular Israelis feel constrained by the religious sanctions imposed on them. Many businesses close on Shabbat, including many forms of public transportation, restaurants, and Israeli airline El Al. In order for a Jewish couple to be formally married in Israel, a couple has to be married by a rabbi. Jewish married couples can only be divorced by a rabbinical council. Many secular Israelis may go abroad to be married, often in Cyprus. Marriages officiated abroad are recognized as official marriages in Israel. Also, all food at army bases and in cafeterias of government buildings has to be kosher, even though the majority of Israelis do not follow these dietary laws. Many religious symbols have found their way into Israeli national symbols. For example, the flag of the country is similar to a tallit, or prayer shawl, with its blue stripes. The national coat of arms also displays the menorah. However, some viewpoints argue that these symbols can be interpreted as ethnic/cultural symbols too, and point out that many secular European nations (Sweden, Georgia, and Turkey) have religious symbols on their flags. Reports have considered Israel to be a secular state, and its definition as a "Jewish state" refers to the Jewish people, who include people with varying relations to the Jewish religion including non-believers, rather than to the Jewish religion itself.[104]

- Under the terms of its preamble, the Constitution of Kiribati is proclaimed by "the people of Kiribati, acknowledging God as the Almighty Father in whom we put trust". However, there is no established church or state religion, and article 11 of the Constitution protects each person's "freedom of thought and of religion, freedom to change his religion or belief", and freedom of public or private religious practice and education.[105]

- Under the terms of the National Pact of 1920, senior positions in the Lebanese state are strictly apportioned by religion:

- the President of the Republic must be Maronite Christian;

- the Prime Minister of the Republic must be Sunni Muslim;

- the Speaker of the Parliament must be Shi'a Muslim;

- the Deputy Speaker of the Parliament and the Deputy Prime Minister must be Greek Orthodox;

- the Chief of the General Staff must be Druze.

- Under the terms of the National Pact of 1920, senior positions in the Lebanese state are strictly apportioned by religion:

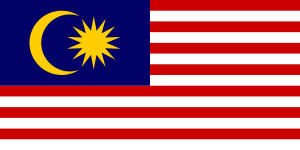

- In Article 3 of the Constitution of Malaysia, Islam is stated as the official religion of the country: "Islam is the religion of the Federation; but other religions may be practiced in peace and harmony in any part of the Federation." In 1956, the Alliance party submitted a memorandum to the Reid Commission, which was responsible for drafting the Malayan constitution. The memorandum quoted: "The religion of Malaya shall be Islam. The observance of this principle shall not impose any disability on non-Muslim nationals professing and practicing their own religion and shall not imply that the state is not a secular state."[106] The full text of the Memorandum was inserted into paragraph 169 of the Commission Report.[107] This suggestion was later carried forward in the Federation of Malaya Constitutional Proposals 1957 (White Paper), specifically quoting in paragraph 57: "There has been included in the proposed Federal Constitution a declaration that Islam is the religion of the Federation. This will in no way affect the present position of the Federation as a secular State...."[108] The Cobbold Commission also made another similar quote in 1962: "....we are agreed that Islam should be the national religion for the Federation. We are satisfied that the proposal in no way jeopardises freedom of religion in the Federation, which in effect would be secular."[109] In December 1987, the Lord President of the Supreme Court, Salleh Abas described Malaysia as governed by "secular law" in a court ruling.[110] In the early 1980s, then-prime minister Mahathir Mohamad implemented an official programme of Islamization,[111] in which Islamic values and principles were introduced into public sector ethics,[112] substantial financial support to the development of Islamic religious education, places of worship and the development of Islamic banking. The Malaysian government also made efforts to expand the powers of Islamic-based state statutory bodies such as the Tabung Haji, JAKIM (Department of Islamic development Malaysia) and National Fatwa Council. There has been much public debate on whether Malaysia is an Islamic or secular state.[113]

- Article 19 of the 2008 Myanmar constitution states that "The State recognizes the special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the State." while Article 20 mentions "The State also recognizes Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Animism as the religions existing in the Union on the date on which the State Constitution comes into force."[114] The government pursues a policy of religious pluralism and tolerance in the country, as stipulated in Article 21 of its constitution, "The State shall render assistance and protect as it possibly can the religions it recognizes." In 1956, the Burmese ambassador in Indonesia U Mya Sein quoted that "The Constitution of the Union of Burma provides for a Secular State although it endorses that Buddhism is professed by the majority (90 per cent) of the nation."[115] While Buddhism is not a state religion in Myanmar, the government provides funding to state Universities to Buddhist monks, mandated the compulsory recital of Buddhist prayers in public schools and patronises the Buddhist clergy from time to time to rally popular support and political legitimization.[116]

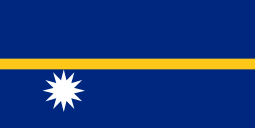

- The Constitution of Nauru opens by stating that "the people of Nauru acknowledge God as the almighty and everlasting Lord and the giver of all good things". However, there is no state religion or established church, and article 11 of the Constitution protects each person's "right to freedom of conscience, thought and religion, including freedom to change his religion or beliefs and freedom", and right to practice his or her religion.[117]

- Norway changed the wording of the constitution on May 21, 2012, to remove references to the state church. Until 2017, the Church of Norway was not a separate legal entity from the government. In 2017, it was disestablished and became a national church, a legally distinct entity from the state with special constitutional status. The King of Norway is required by the Constitution to be a member of the Church of Norway, and the church is regulated by a special canon law, unlike other religions.[118]

- The Romanian constitution declares freedom of religion, but all recognized religious denominations remain state-funded. Since 1992, these denominations have also maintained a monopoly on the sale of religious merchandise, which includes all candles except decorative candles and candles for marriage and baptism. It is currently illegal in Romania to sell cult candles without the approval of the Eastern Orthodox Church or of another religious denomination which employs candles (law 103/1992, appended O.U.G. nr.92/2000 to specify penalties).[119] Romania recognizes 18 denominations/religions: various sects of the Orthodox Church, the Catholic Church, Protestantism and Neo-Protestantism (including Jehovah's Witnesses), Judaism and Sunni Islam.[120] Unrecognized cults or denominations are not prohibited, however.

- The Sri Lankan constitution[121] does not cite a state religion. However, Article 9 of Chapter 2, which states "The Republic of Sri Lanka shall give to Buddhism the foremost place, and accordingly, it shall be the duty of the State to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana" makes Sri Lanka an ambiguous state with respect to secularism. In 2004, Jathika Hela Urumaya proposed a constitutional amendment that would make a clear reference to Buddhism as the state religion, which was rejected by the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka.[122]

- The Swiss Confederation remains secular at federal level. However, the constitution begins with the words "In the name of Almighty God!"

- 24 of the 26 cantons support either the Catholic Church or the Swiss Reformed Church.

- The Syrian constitution requires the president to be a Muslim and Islamic jurisprudence to be a major source of legislation[123] despite the governments of Bashar al-Assad and his father before him, Hafez al-Assad, being largely secular in practice.

- Section 9 of the 2007 Thai constitution states that "The King is a Buddhist and Upholder of religions", and section 79 makes another related reference: "The State shall patronise and protect Buddhism as the religion observed by most Thais for a long period of time and other religions, promote good understanding and harmony among followers of all religions as well as encourage the application of religious principles to create virtue and develop the quality of life."[124] The United States Department of State characterised that these provisions provides Buddhism as the de facto official religion of Thailand. There have been calls by Buddhists to make an explicit reference to Buddhism as the country's state religion, but the government has turned down these requests.[122] Academics and legal experts have argued that Thailand is a secular state as provisions in its penal code are generally irreligious by nature.[125]

- The Constitution of Tonga opens by referring to "the will of God that man should be free". Article 6 provides that "the Sabbath Day shall be kept holy", and prohibits any "commercial undertaking" on that day. Article 5 provides: "All men are free to practice their religion and to worship God as they may deem fit in accordance with the dictates of their own worship consciences and to assemble for religious service in such places as they may appoint". There is no established church or state religion.[126] Any preaching on public radio or television is required to be done "within the limits of the mainstream Christian tradition", though no specific religious denomination is favoured.[127]

- The Church of England is the established state religion of England only. It is no longer established in Northern Ireland or Wales since the Anglican Church in these respective regions (Church of Ireland and Church in Wales) received autonomy from the main Church of England in 1871 and 1920 respectively. In Scotland, the generally Protestant Church of Scotland has an ambiguous, special constitutional status as national church. Furthermore, unlike its Welsh and Irish counterparts, the Anglican Church in Scotland (the Scottish Episcopal Church) never received established status; however, like the Church of Ireland and Church in Wales, the Scottish Episcopal Church is autonomous from the main Church of England.

- The respective churches of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales are all, however, still in full communion with the Anglican Church.

- Two archbishops and 24 senior diocesan bishops of the Church of England (the Lords Spiritual) have seats in the House of Lords, where they participate in debates and vote on decisions affecting the entire United Kingdom.

- The full term for the expression of the Crown's sovereignty via legislation is the Crown-in-Parliament under God. At the coronation, The sovereign is anointed with consecrated oil by the Archbishop of Canterbury in a service at Westminster Abbey and must swear to maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel, maintain Protestantism in the United Kingdom, specifically the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof as by established law in England.

- Thus, though the Church of Ireland is no longer established and the Church of England has been disestablished in Wales as the Church in Wales, the Crown is still bound to protect Protestantism in general in the whole of the United Kingdom by the Coronation Oath Act 1688 and the Bill of Rights, and to protect the Church of Scotland by the Act of Union 1707.[129] All Members of Parliament (MPs) must declare their allegiance to the Queen in order to take their seat. Each individual MP, however, can choose whether or not to affirm a religious oath.

- The Church of England is the established state religion of England only. It is no longer established in Northern Ireland or Wales since the Anglican Church in these respective regions (Church of Ireland and Church in Wales) received autonomy from the main Church of England in 1871 and 1920 respectively. In Scotland, the generally Protestant Church of Scotland has an ambiguous, special constitutional status as national church. Furthermore, unlike its Welsh and Irish counterparts, the Anglican Church in Scotland (the Scottish Episcopal Church) never received established status; however, like the Church of Ireland and Church in Wales, the Scottish Episcopal Church is autonomous from the main Church of England.

- The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

- Some U.S. states have laws that would prevent atheists from holding office, such as Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Texas. However, these laws were declared unconstitutional in the U.S. Supreme Court case Torcaso v. Watkins on the basis that they violated the first and fourteenth amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

- A clause in Article 11 of Treaty of Tripoli between the U.S. and present-day Libya states that "the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion."

- The United States Senate does, however, come into session with a prayer by an appointed chaplain. Citing violation of the separation of church and state, there have been numerous attempts to abolish the position.

- The American Pledge of Allegiance contains the phrase "one nation under God."

- The official motto of the United States is "In God We Trust."

- The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

- The preamble to the Constitution of Vanuatu provides that the Republic of Vanuatu is "founded on traditional Melanesian values, faith in God, and Christian principles". There is no state religion or established church, and article 5 of the Constitution protects "freedom of conscience and worship."[130]

See also

| Look up secular in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Notes

- ↑ Madeley, John T. S. and Zsolt Enyedi, Church and state in contemporary Europe: the chimera of neutrality, p. 14, 2003 Routledge

- ↑ Jean Baubérot The secular principle Archived February 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Richard Teese, Private Schools in France: Evolution of a System, Comparative Education Review, Vol. 30, No. 2 (May, 1986), pp. 247–59

- ↑ Twinch, Emily. "Religious charities: Faith, funding and the state". Article dated 22 June 2009. Third Sector – a UK Charity Periodical. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ↑ "Department for Education". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ [Sejdic and Finci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina (application nos. 27996/06 and 34836/06) found a violation of the non-discrimination overarching right vis-à-vis all other rights on a wider subject from often arbitrary funding of social charities viz. rights afforded by law Art. 1 of Prot. No. 12, namely protecting "any right set forth by law". The convention introduces a general prohibition of discrimination in legally enshrined state action, as well as where rights under the convention such as an education or health care are funded. A superior level of services supported by religious bodies is permitted.]

- ↑ "Coronation Oath". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "How members are appointed". UK Parliament. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Harris Interactive: Resource Not Found". Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "A Portrait of "Generation Next"". Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 9 January 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Secularization and Secularism – History and Nature of Secularization and Secularism to 1914". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - Angola Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Article 2 of Constitution

- ↑ "Botswana". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Leaders say Botswana is a secular state Archived February 10, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Article 31 of Constitution

- ↑ Article 1 of Constitution Archived October 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Preamble of Constitution

- ↑ "Constitution of Cape Verde 1992". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Article 1 of Constitution

- ↑ "Côte d'Ivoire's Constitution of 2000" (PDF).

- ↑ "Constitution de la République démocratique du Congo". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - Congo-Brazzaville - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - Ethiopia - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Article 2 of Constitution Archived October 19, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.Ghana

- ↑ Article 1 of Constitution Archived September 13, 2004, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Article 1 of Constitution Archived November 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

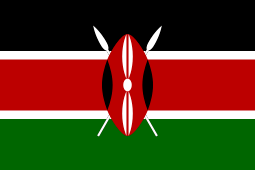

- ↑ "The Constitution of Kenya" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

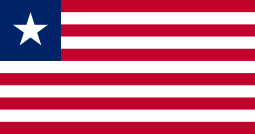

- ↑ "ICL - Liberia - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

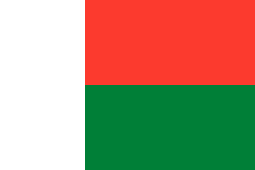

- ↑ "Madagascar's Constitution of 2010" (PDF).

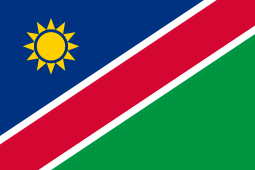

- ↑ Preamble of Constitution Archived September 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "ICL - Namibia - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ John L. Esposito. The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press US, (2004) ISBN 0-19-512559-2 pp.233-234

- ↑ "Nigerian Constitution". Nigeria Law. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "Senegal". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "The right to differ religiously.(News)". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ PART ONE: SOUTH SUDAN AND THE CONSTITUTION 8. RELIGION

- 1 2 Article 7.1 of Constitution

- ↑ "CONSTITUTION OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Eastimorlawjournal.org". Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT)". Archived from the original on 2015-03-28.

- ↑ "ICL - Japan - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-09-24. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "ICL - South Korea - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Article 1 of Constitution Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Religious Intelligence - News - Nepal moves to become a secular republic Archived January 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Article 2, Section 6 of Constitution Archived March 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 design: Babenko Vladimir, redesign: Davidov Denis. "Êîíñòèòóöèÿ Ðîññèéñêîé Ôåäåðàöèè". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ See Declaration of Religious Harmony, which explicitly states the secular nature of society

- ↑ "INTRODUCTION TO THE WEB VERSION OF THE CONSTITUTION". Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - Taiwan - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Tajikistan's Constitution of 1994 with Amendments through 2003" (PDF).

- ↑ "Constitution of Turkmenistan". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ "ICL - Vietnam - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - Albania - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - Austria Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Racius, Egdunas (19 September 2013). "Yearbook of Muslims in Europe". BRILL – via Google Books.

- ↑ "ICL - Bosnia and Herzegovina - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms Archived 2008-04-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "ICL - Estonia - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - France Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - The Fundamental Law of Hungary -- Part I". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Article 44.2.1º of the Constitution of Ireland - The State guarantees not to endow any religion.

- ↑ "ICL - Latvia - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Article 11 of the Constitution Archived June 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Article 1 of Constitution

- ↑ "Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Article 16 of Constitution" (PDF). Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ The Swedish head of state must according to the Swedish Act of Succession adhere to the Augsburg Confession

- ↑ "ICL - Belgium - Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- ↑ "Article 8 of the Cuban Constitution". Archived from the original on April 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Honduras: Constitución de 1982". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Honduras - THE CONSTITUTION". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ICL - Australia Constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Fiji Archived 2016-02-06 at the Wayback Machine., 2013

- ↑ "Constitution of the Federated States of Micronesia".

- ↑ "Article 19 of the Brazilian Constitution".

- ↑ Since 1925 by the Chilean Constitution of 1925 (article 10), and "1980 Chilean Constitution Article 19, Section 6º". Archived from the original on 2006-12-07.

- ↑ (PDF) http://www.iclrs.org/content/blurb/files/Colombia.1.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Articles 1, 11, 26, and 66.8 of the Ecuadorian Constitution" (PDF).

- ↑ "Article 50° of the Peruvian Constitution". Archived from the original on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, Chapter III, Article 5".

- ↑ "Americanchronicle.com". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20170616153746/http://thediplomat.com/2017/06/samoa-officially-becomes-a-christian-state/

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of Armenia". president.am. 27 November 2005.

- ↑ "2A. The state religion". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "12".

- ↑ "Secularism is back in Bangladesh, rules High Court".

- ↑ "Bangladesh court upholds Islam as religion of the state". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ "As Bangladesh court reaffirms Islam as state religion, secularism hangs on to a contradiction". Scroll.In. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ "Bangladesh`s court restores `secularism` in Constitution". Zee News.

- ↑ "Bangladesh's Constitution of 1972, Reinstated in 1986, with Amendments through 2011" (PDF). Constitute. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ "Google Translate". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20150103200933/http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/ElSalvador1983English.pdf

- 1 2 "Georgia's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2013" (PDF).

- ↑ Georgia: International Religious Freedom Report 2007. U.S. Department of State. Accessed on February 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Instant Indonesia: Religion of Indonesia". Swipa. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ↑ Yang, Heriyanto (2005). "The History and Legal Position of Confucianism in Post Independence Indonesia" (PDF). Marburg Journal of Religion. 10 (1). Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ↑ Hosen, N (2005-09-08). "Religion and the Indonesian Constitution: A Recent Debate" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 36: 419. doi:10.1017/S0022463405000238. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ "Tugas dan Fungsi Menteri Departemen". tunas63. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Religion and the Secular State in Israel. Page 421-422: " Not every Jew, in Israel or elsewhere, is a religious individual. It is in collective terms that religion has been an essential ingredient in the self-definition and behavior of the Jews, believers or not, observant or not. For that reason, it was aptly stated that Judaism conceived of itself not as a denomination but as the religious dimension of the life of a people. Hence peoplehood is a religious fact in the Jewish universe of discourse. In its traditional self-understanding, Israel is related not to other denominations but to the “‟nations of the world‟… Israel‟s… body is the body politic of a nation. a denomination but as the religious dimension of the life of a people. Hence peoplehood is a religious fact in the Jewish universe of discourse. In its traditional self-understanding, Israel is related not to other denominations but to the “‟nations of the world‟… Israel‟s… body is the body politic of a nation". Page 423: "It seems reasonable to accept that the reference to Israel as a “Jewish State” is equivalent to stating that in historical, political, and legal terms, it is the state of the Jewish people". Page 424: "all refer to a Jewish state, and Jewish means, in all of them, pertaining to Jews, namely the individuals seeing themselves as composing the Jewish people, or nation, or community. It clearly does not mean the body of religious precepts, commands or convictions regulated by the Halakha, the Jewish religious law developed over centuries.".

- ↑ "Constitution of Kiribati". Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Tan Sri Datuk Ahmad Ibrahim, Our Constitution and Islamic Faith, p. 8, 25 August 1987, New Straits Times

- ↑ Islam's status in our secular charter, Richard Y.W. Yeoh, Director, Institute of Research for Social Advancement, 20 July 2006, The Sun, Letters (Used by permission)

- ↑ Federation of Malaya Constitutional Proposals Kuala Lumpur: Government Printer 1957–Articles 53-61 (PDF document) hosted by Centre for Public Policy Studies Malaysia, retrieved 8 February 2013

- ↑ The birth of Malaysia: A reprint of the Report of the Commission of Enquiry, North Borneo and Sarawak, 1962 (Cobbold report) and the Report of the Inter-governmental Committee, (1962–I.G.C. report), p. 58

- ↑ Wan Azhar Wan Ahmad, Historical legal perspective, 17 March 2009, The Star (Malaysia)

- ↑ Zainon Ahmad PAS remains formidable foe despite defeat, p. 2, 10 Sep 1983, New Straits Times

- ↑ Moderate policy will ensure UMNO leads, says Mahathir, p. 1, 25 April 1987, New Straits Times

- ↑ Zurari AR, History contradicts minister’s arguments that Malaysia is not secular Archived 2013-02-25 at the Wayback Machine., October 22, 2012, The Malaysian Insider

- ↑ Temperman (2010), p. 77

- ↑ Burma. Dept. of Information and Broadcasting, Burma. Director of Information, Union of Burma, 1956 Burma, Volume 6, Issue 4, p. 84

- ↑ Juliane Schober, BUDDHISM, VIOLENCE AND THE STATE IN BURMA (MYANMAR) AND SRI LANKA, Universitat Passau, retrieved 19 February 2013

- ↑ "THE CONSTITUTION OF NAURU*". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "International Humanist and Ethical Union - State and Church move towards greater separation in Norway". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Legea 103/1992 dreptul exclusiv al cultelor religioase pentru producerea obiectelor de cult - Textul integral al legilor".

- ↑ http://culte.gov.ro/?page_id=57

- ↑ ":.The Constitution of Sri Lanka: An Introduction .:". Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- 1 2 Temperman (2010), p. 66

- ↑ "Constitution of the Syrian Arabic Republic – Syrian Arab News Agency". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2550 (2007) (Unofficial translation), FOREIGN LAW BUREAU, OFFICE OF THE COUNCIL OF STATE

- ↑ Andrew Harding, Buddhism, Human Rights and Constitutional Reform in Thailand, Asian Journal of Comparative Law, Volume 2, Issue 1 2007 Article 1, retrieved 19 February 2013

- ↑ "Tonga". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "2010 Report on International Religious Freedom - Tonga", United States Department of State, 2011

- ↑ http://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-information-office/g07.pdf

- ↑ http://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons/lib/research/briefings/snpc-00435.pdf

- ↑ Constitution of Vanuatu Archived October 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

Bibliography

- Temperman, Jeroen, State Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law: Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance, BRILL, 2010, ISBN 9004181482