Iban people

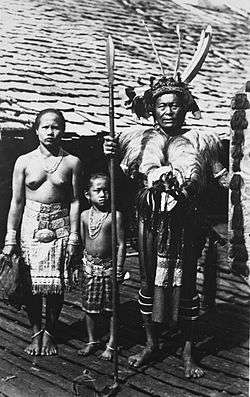

A traditional Iban family, circa 1920–1940. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approximately 1,052,400 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Borneo: | |

| 745,400[1] | |

West Kalimantan | 287,000[2] |

| 20,000[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Iban, Indonesian/Malaysian; most notably the Sarawak Malay dialect of the Malaysian language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Animism, some minorities Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kantu, Dayak Mualang, Semberuang, Bugau and Sebaru | |

The Ibans or Sea Dayaks are a branch of the Dayak peoples of Borneo, in South East Asia. Most Ibans are located in the Malaysian state of Sarawak. It is believed that the term "Iban" was originally an exonym used by the Kayans, who referred to the Sea Dayaks in the upper Rajang river region when they initially came into contact with them as the "Hivan".

Ibans were renowned for practicing headhunting and tribal/territorial expansion, and had a fearsome reputation as a strong and successful warring tribe in the past. Since the arrival of Europeans and the subsequent colonisation of the area, headhunting gradually faded out of practice although many other tribal customs and practices as well as the Iban language continue to thrive. The Iban population is concentrated in Sarawak, Brunei, and in the Indonesian province of West Kalimantan. They traditionally live in longhouses called rumah panjai.[4][5]

Nowadays the Ibans tend to become more urbanised, as most longhouses are built using modern materials such as concrete and brick, and equipped with not only basic domestic necessities of sewage, electricity, and running water but also with accessibility to modern facilities such as (tar sealed) roads, telephone lines and the Internet.

Ibanic Dayak regional groups

Although Ibans generally speak various dialects which are mutually intelligible, they can be divided into different branches which are named after the geographical areas where they reside.

- The majority of Ibans who live around the Lundu and Samarahan region are called Sebuyaus.

- Ibans who settled in areas in Serian district (places like Kampung Lebor, Kampung Tanah Mawang and others) are called Remuns. They may be the earliest Iban group to migrate to Sarawak.

- Ibans who originated from Sri Aman area are called Balaus.

- Ibans who come from Betong, Saratok and parts of Sarikei are called Saribas.

- The original Iban Lubok Antu Ibans are classed by anthropologists as Ulu Ai/batang ai Ibans.

- Ibans from Undup are called Undup Ibans. Their dialect is somewhat a cross between the Ulu Ai dialect and the Balau dialect.

- Ibans living in areas from Sarikei to Miri are called Rajang Ibans. This group is also known as "Bilak Sedik Iban". They are the majority group of the Iban people. They can be found along the Rajang River, Sibu, Kapit, Belaga, Kanowit, Song, Sarikei, Bintangor, Bintulu and Miri. Their dialect is somewhat similar to the Ulu Ai or lubok antu dialect.

In West Kalimantan (Indonesia), Iban people are even more diverse. The Kantu, Air Tabun, Semberuang, Sebaru, Bugau, Mualang, and many other groups are classed as "Ibanic people" by anthropologists. They can be related to the Iban either by the dialect they speak or their customs, rituals and their way of life.

Language

The Iban speaks more or less one language with a variation in intonation according to the region from which each comes from. They have a rich oral literature, noted by Freeman, who stated: "The Iban probably has more oral literature than the Greek." There is a body of oral poetry which is recited by the Iban depending on the occasion.

The recitation of pantun and various kinds of leka main (traditional poetry) is a particularly important aspect of festivals. Any ordinary person can recite poetry for entertainment and customary purposes but sacred incantations to invoke deities are only recited by specialists, who are either a manang (shaman) or lemambang (bard) or tukang sabak.

According one Iban scholar,[6][7] the leka main (poems, proses, and folklore) for Iban Dayaks can be categorised into three major groups: leka main pemerindang (for entertaining purposes), leka main adat basa (for customary purposes) and leka main invokasyen (for invocation purposes).

These invocatory incantations must be accompanied with piring (ritual offerings) to appease the gods invoked during the restival. The incantation can last the whole night of the festival, and the next morning a pig is sacrificed to use its liver for divination with its liver which is interpreted to forecast the luck, fortune, health and success of the feast host and his family in the future.

Religion and belief

For hundreds of years, the ancestors of the Iban practiced animistic beliefs, although after the arrival of James Brooke, many were influenced by European missionaries and converted to Christianity. Although the majority are now Christian; many continue to observe both Christian and traditional ceremonies, particularly during marriages or festivals, although some ancestral practice such as 'Miring' are still prohibited by certain churches. After being Christianized, the majority of Iban people have changed their traditional name to a Hebrew-based "Christian name" such as David, Christopher, Janet, Magdalene, Peter or Joseph, but a minority still maintain their traditional Iban name or a combination of both with the first Christian name followed by a second traditional Iban name such as David Dunggau, Kenneth Kanang, Christopher Changgai, Janet Jenna or Joseph Jelenggai.

The longhouses of Iban Dayaks are constructed in such a way to act as an accommodation and a religious place of worship. The entire structure is built as a standing tree when viewed along its length or sideways. The open veranda (tanju) is exposed to sunrise (Mata Ari tumboh), thus facing to the east and the sunset (Mata Ari padam) is the back of the longhouse. The first pillar to be erected during the longhouse construction is the tiang pemun (the main post) from which the pun ramu (the bottom of any tree trunks) is determined and followed along the longhouse construction. Any subsequent rituals will refer to the tiang pemun and pun ramu.

Iban religion and pantheon

The Iban religion involves worshiping and honouring at least four categories of beings, i.e. Petara, the supreme god, and his seven deities, the holy spirits of Orang Panggau Libau and Gelong, the ghost spirits (Bunsu Antu) and the souls of dead ancestors. Some Iban categorizes these gods into beings from the sky (ari langit) which refers to gods living in the sky, from the tree tops (vari pucuk kayu}}) which refers to omen birds, from the land/soil (ari tanah) which refers to augury animals, snakes and reptiles, and from the water (ari ai) which refers to fishes and water creatures.

The supreme God is called Bunsu (Kree) Petara, and is sometimes called Raja Entala or even Tuhan Allah Taala (Arabic defines the article al- "the" and ilāh "deity, god" to al-lāh meaning "the [sole] deity, God") in modern times. The Iban calls this supreme god who creates the universe by the three names of Seragindi which makes the water (ngaga ai), Seragindah which makes the land (ngaga tanah) and Seragindit which makes the sky (ngaga langit).

There are seven main petaras (deities or gods or regents) of Iban Dayaks who act as the messengers between human beings and God. These deities are the children of Raja Jembu and the grandchildren of Raja Burong.[9] Their names are as follows:

- Sengalang Burong the god of war

- Biku Bunsu Petara (female) the high priest

- Sempulang Gana the god of agriculture along with his father-in-law Semarugah as the god of land

- Selempandai/Selempeta/Selempetoh the god of creation and procreation.

- Menjaya Manang the god of health and shamanism being the first manang bali

- Anda Mara the god of wealth and fortune.

- Ini Andan/Inee (female) the natural-born doctor and the god of justice

In addition to these gods, there are mystical people namely the orang Panggau Libau and Gelong with the most notable ones being Keling and Laja, and Kumang and Lulong who often help the Iban Dayaks to be successful in life and adventures.

Other spirits are called bunsu jelu (animal spirits), antu utai tumboh (plant spirits), antu (ghosts) such as antu gerasi (huntsman) and antu menoa (place spirits like hills or mounts). These spirits can be helpful, cause sickness or even madness.

The souls of dead ancestors are invoked by the Iban when seeking their blessings. They pay their respects to their souls during Gawai Antu (Festival of the Dead) and when visiting their graves.

Stages of Iban propitiation

Masing in 1981 and Sandin clearly categorise Iban's propitiation and worshiping into three main successive stages of increasing importance, complexity and intensity, i.e. bedara (serving and distributing offerings), gawa (literally working) and gawai (festival).

Bedara can be divided into bedera mata (unripe rite) if the service is performed inside the family room (bilik) and bedara mansau (ripen rite) where it is carried out at the family gallery (ruai). Other specific miring rituals are called minta ujan (asking for rain), minta panas (asking for sunniness), berunsur (soul cleansing), mudas (omen appreciation), muja menua (praying to the region), pelasi menua (cleansing the territory), genselan menoa (smearing the earth with blood) or nasih tanah (paying land rent). Other bedara or miring ceremonies include makai di ruai/ngayanka asi (dinner at the gallery), sandau ari (mid-day ceremony) and enchaboh arong (head receiving ceremony).

Gawa includes all the medium-sized rites that normally involve one day and one night of ritual incantations by a group of bards such as gawa beintu-intu (self-caring rituals) and gawa tuah (fortune ritual). There are various types of gawa beintu-intu such as imang sukat (Life Measuring Chant), timang bulu (Human Mantle Chant), timang buloh ayu (Soul Bamboo Chant), timang panggang (Jar Board Chant), timang panggau (Wooden Platform Chant) and timang engkuni (House Post Chant). As this category of rites involves mainly timang (chant), it is also normally called nimang (chanting). Gawa Tuah has three stages called nimang ngiga tuah (fortune seeking), nimang namaka tuah (fortune welcoming) and madamka tuah ( fortune termination).

Gawai comprises seven main categories of large festivals, which mostly involve ritual incantation by a group of lemambang bards that can last from several to seven successive days and nights to follow the paddy farming cycle in succession of stages. These categories are namely gawai bumai (farming festivals), gawai amat/asal (real/original festival) or gawai burong (bird festival), gawai tuah (fortune festival), gawai lelabi (River turtle/marriage festival), gawai sakit (Healing festival), gawai antu (festival of the dead) and gawai ngar (dyeing/weaving festival).

Iban piring or ritual offerings

The Iban leka piring which is the number of each offering item is basically according to the single odd numbers which are piring turun 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9. Leka piring (the number of each offering item) depends on how many deities are to be invited and presented with offerings which number should normally be an odd figure.

The list of deities to be prayed to and offered with foods and drinks are as follows:

- Sengalang Burong – when preparing for war or major event like participating in election. Gawai Burong is usually held to honor him and to seek his blessing.

- Raja Simpulang Gana – when dealing with farming related activities, during Gawai Umai and related festivals.

- Raja Menjaya & Ini Inda – when asking for better health during Gawai Sakit and related activities (e.g. bemanang).

- Anda Mara – when seeking good fortune and material wealth, during Gawai Pangkong Tiang.

- Selampandai – when seeking blessings in marriage, growth of children, or fertility, during Gawai Melah Pinang.

- Raja Semarugah – when seeking permission to use land for construction and other activities like agricultural activities (when erecting the first pole).

- Keling and orang Panggau and Gelong – when seeking their help to go to war, election, defence from enemies, or when seeking their help to invite gods to festivals.

- Souls of dead ancestors – when seeking their blessing and showing respect for their soul. Usually during Gawai Dayak and when visiting their graves.

- Bunsu Antu – as and when instructed in dreams.

The set of offerings (agih piring) is dedicated to each part of the long house room (bilek) such as bilek four corners, tanju (verandah), ruai (gallery), dapur (kitchen), benda beras (rice jar), pelaboh (verandah behind the kitchen), farm (umai), garden of rubber or black pepper, other possessions like long boat (prau) with its engine, tajau (jar), cannon (meriam) and modern items like, car, motorcycle, etc. as deemed fit and necessary.

The rule on how to choose the leka piring according to its purpose is as follows:

- Leka piring 1 – piring jari (personal offering to God)

- Leka piring 3 – piring ampun/seluwak (for apologies or economy)

- Leka piring 5 – piring minta/ngiring bejalai (for requests or journey)

- Leka piring 7 – piring gawai/bujang berani (for festivals or brave men)

- Leka piring 8 – piring nyangkong (for including others)

- Leka piring 9 – piring nyangkong/turu (for including others and any leftover offering items are placed together)

- Leka lebih ari 9 (11, 13, 15, 18 up to 30) – piring turu (leftover offering items must be all offered and cannot be eaten). These are for piring tanam (base) or piring pucuk (tip) (offerings for setting up pnadong/ranyai (ritual shrine) during major festivals.

The number of offerings (leka pring) can be varied according to the importance of the god or item.

The basic items for the piring offerings include at least the following items:

- betel nuts, sirih leaves, sedi leaves and kapu chalk

- cigar leaves and tobacco

- 'senupat (sacheted glutinous rice)

- sungkoi (wrapped glutinous rice)

- asi pulut pansoh (glutinous rice cooked in bamboo container)

- tumpi (flattened glutinous rice flour cake)

- asi manis (semi-fermented glutinous rice)

- hard-boiled chicken eggs (telu mansau) and uncooked chicken eggs (telu mata)

- rendai or letup (pop glutinous paddy)

- tuak (alcoholic drink fermented from glutinous rice with yeast)

- penganan (disc-shaped cake made from glutinous rice flour which is deep-fried in cooking oil)

- cuwan (flowery-shaped molded biscuit made from glutinous rice flour)

- sarang semut (ant nest biscuit made of glutinous rice)

- A live chicken or a pig is caught and kept ready within a short distance

So it can be seen from the list of items above that it is customary to offer guests or gods cigarettes, sireh leaves and betel nuts as courtesy dictates. These first items are placed into a brass container which is always ready by each Iban family in the longhouse in anticipation of guests. Secondly it is necessary to offer food and drinks as essential items. It is customary to ask whether guests have already eaten or to invite them straight away to eat once food and dishes are ready, especially during meal times. In addition, biscuits and deserts are offered after meals as a sign of hospitality in Iban custom. All these ingredients are put onto plates or woven baskets made of bamboo or rattan which are then arranged in several rows on a ritual pua kumbu (ceremonial blanket). In urgent or emergency cases, ilum pinang (an odd number of lumps of sireh, betel nuts and cigarettes are offered because many Iban would always carry these items anywhere they go or during their travels to negate any bad omens or to show thanks for a good augury. A small offering platform may be built to place this simple offering and a short sampi prayer is recited. A fire may be also lit as necessary in recognition of the omen and to warm up those present.

A number of worthy men are chosen or nominated to divide and serve the offerings onto old clay plates (plastic plates are to be avoided because they are recent invention and indicative of cheapness or lower status unless clay plates are not available or cannot be borrowed from neighbors; at a minimum, the main offering plate must be on a clay plate). Women can be selected especially if the offering is done within the bilek room. Alternatively, if plates are not available as in the old times or interior upriver regions, square-bottom baskets (called kalingkang) made of bamboo split skins, woven-concave plates made of rattan or randau coils with daun buan or daun long leaves are used. Some offerings are placed on a long bamboo pole with a conical receptacle at its top (teresang). A bigger and more important set of offerings is served on tabak (brass tray) or bebendai (brass snare).

The piring items are taken by those chosen one by one in the order listed above or some people take the oily penganan (sweet disc shaped pancake) as the first favorite delicacy and placed it in the middle of the place or container to prevent stickiness of the fingers and followed by other items. The aim is to serve and present the offerings beautifully and as attractive as possible to arouse the appetite of the guests or gods.

As the propitiation increases in importance and size from normal and brief bedara offerings, to medium-sized gawa ceremonies to huge and lengthy gawai festivals, the number and set of offerings also increases accordingly. All major and minor gods are offered piring offerings to ensure prosperity and peace during the occasions and in life.

The genselan (animal offering) is normally made in the form of a chicken or a pig, depending on the scale of the ceremony. For small ceremonies, e.g. bird omens, chickens will be used, while on larger occasions such as animal omens, pigs will be sacrificed. The chicken feathers are pulled and smeared into the blood of the chicken whose throat has been slit and the chicken head may be put onto the main offering plate. For festivals, one or several pigs and tens of chickens may be sacrificed to appease the deities invoked and to serve human guests invited to the festivals within the territorial domain of the feast chief. The pig head may be offered with the offerings or buried into ground. The body of the chicken or pig and leftover piring materials can be eaten by guests, provided the chicken or pig is not killed or sacrificed to cleanse sin or bad luck like in incest cases which can cause havoc (ngudi menua) in the Iban faith. If not eaten, the body may be buried as sacrifice.

Iban omens and augury

%2C_Borneo%2C_Sarawak%2C_Iban%2C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

The augury system for the Iban Dayaks depends on several ways to obtain indicative omens for decision making and action taking:

- Dream to present charm gifts or sumpah (curse) by spirits which is believed to have a long or lifetime effect.

- Omen animals (burong laba) such as deer barkings which are also believed to have lifetime effects.

- Omen birds (burong Mali) which are believed to have temporary effects limited to certain activities with the hands e.g. that year of farming.

- Pig liver divination (Betenong ati babi) at the end of a certain festival to predict future luck.

- Areca nut blossom flower (betenong ngena bungai pinang) after the pelian healing ceremony.

- nampok (seclusion) or betapa (isolation)

The omens can be either purposely sought via dream during sleep, in the langkau burong (bird hut), pig liver divination and seclusion/isolation or received unexpectedly especially the animal and bird omens e.g. while working at farms or walking to enemy country.

The omen animals under Sempulang Gana are:

- Tuchok/Belangkiang lizard

- Ulat bulu caterpillar

- Ingkat tarsier

- Bengkang slow loris

- Bayak monitor lizard

- Landak porcupine

- Tengiling pangolin

- Pelandok mouse deer

- Kijang barking deer

- Rusa sambar deer

- Jani babas wild boar

- Jugam sun bear

- Remaong dawn Leopard cat

The omen birds of Iban Dayaks are seven in total namely:

- ketupong also known as jaloh or kikeh or entis (rufous piculet),

- beragai (scarlet-rumped trogon),

- pangkas (maroon woodpecker) on the right hand of the Sengalang Burong's longhouse bilek and

- Bejampong (crested jay),

- embuas (banded kingfisher),

- kelabu papau (Senabong) (Diard's trogon) and

- nendak (white-rumped shama).

Their types of calls, flights, places of hearing and circumstances of the listeners are factors to be considered during the interpretation of the bird omens.

The augural snakes are:

- Tedong cobra

- Kendawang coral snake

- Belalang Hamadryad

- Sawa pyhton

The augury under Selempandai include:

- Sempandai centipede

- Mengalai centipede

- Kemebai milipede

- Sempada

The Iban Dayaks used to believe that deities, spirit heroes, Antu spirits, and dead ancestors could bestow various charms. These included ubat (medicine), pengaroh (amulet), empelias (anti-line of fire) and engkerabun (invisibility). These were believed to give men good health, wealth, fame, long life, rice and jars easily, to make them kebal (invenerable), extraordinarily stronger (kering) than other men. They were also believed to give supernatural powers similar to those of deities or spirits, whose attributes are wanted for rice farming, headhunting, and other activities. For women, the charms are believed to help them to be skillful in weaving.

Iban conversion to Christianity

There are several reasons why some Iban and other Dayaks convert to Christianity:

- Observing the various penti pemali (prohibitions) and superstitions dictated by the traditional augury can make life complicated and introduce delays that will slow down one's progress with life and work.

- The healing (pelian) offered by the manangs is not effective in curing many diseases, e.g. smallpox, cholera (muang ai), dengue, etc.

- Christianity is considered a new branch of knowledge to be adopted and adapted to the traditional customs and way of life, leading to the realization that bad old practices such as headhunting are self-destructive to the survival of the Dayak race as a whole.

- Christianity comes with Western education, which can be used to seek employment on sojourns and upgrade one's standard of living to escape poverty.

- Defeats of Dayaks at the hands of Europeans with better weapons, such as guns and cannons against traditional hand-held weapons such as swords, shields, spears and blowpipes, despite strict adherence to traditional augury practices.

- Some Ibans consider Christianity an extension of human knowledge because it can accommodate some of their traditional practices, e.g. some the ritual festivals can be celebrated in the Christian ways.

- Some churches and pastors prohibit Christian Iban to practice their ancestors' traditional customary ceremonies to honour the Petara (gods), spirits and ancestors but they somehow replace the ceremonial procedures with Christian prayers and practices which propiate the Christian God and thereby still retaining the ceremonial title with the same purpose and function. (However, there is a certain degree of flexibility regarding individual observance).

For the majority of Ibans who are Christians, some Christian festivals such as Christmas, Good Friday, Easter are also celebrated. Most Ibans are devout Christians and follow the Christian faith strictly. Since conversion to Christianity, some Iban people celebrate their ancestors' festivals using Christian ways and the majority still observes Gawai Dayak (the Dayak Festival), which is a generic celebration in nature unless a gawai proper is held and thereby preserves their ancestors' culture and tradition.

Despite the difference in faiths, Ibans of different faiths do help each other during Gawai and at Christmas. Differences in faith are never a problem in the Iban community.[10] The Ibans believe in helping and having fun together. Some elder Ibans are worried that among most of their younger Iban generation, their culture has faded since the conversion to Christianity and the adoption of a more Western style of life. Nevertheless, most Iban embrace modern progress and development.

Iban ritual festivals and rites

Significant traditional festivals, or gawai, to propitiate the above-mentioned gods can be grouped into seven categories which are related to the main ritual activities among the Iban Dayak:

- Farming-related festivals to propitiate the deity of agriculture Sempulang Gana,

- War-related festivals to honor the deity of war Sengalang Burong,

- Fortune-related festivals dedicated to the deity of fortune Anda Mara,

- Procreation-related festival (Gawai Melah Pinang) for the deity of creation Selampandai,

- Health-related festivals for the deity of shamanism Menjaya and Ini Andan and

- Death-related festival (Gawai Antu or Ngelumbong) to invite the dead souls for final separation ritual between the living and the dead.

- Weaving-related festival (Gawai Ngar) for patrons of weaving.

Farming ritual festivals

Because rice farming is the key life-sustaining activity among Dayaks, the first category of festivals is related to agriculture. Thus, there are many ritual festivals dedicated to this foremost vital activity namely:

- Gawai Batu (Whetstone Festival),

- Gawai Benih (Seed Festival),

- Gawai Ngalihka Tanah (or Manggol) (Soil Ploughing Festival),

- Gawai Ngemali Umai (Farm-healing Festival),

- Gawai Matah (Harvest-starting Festival)

- Gawai Ngambi Sempeli (Taking Secondary Paddy Festival),

- Gawai Basimpan (Rice-Keeping) Festival and

- Gawai Tajau (Jar Welcoming Festival).

The Jar festival also invokes Raja Sempulang Gana as the god of agriculture because surplus paddy is used to buy jars and brassware in the past. There is one important rite called mudas for strengthening any omen encountered during farming activity. Several of these festivals have been relegated to simpler or intermediate ceremonies, which mainly involve nimang (incantation) only and are thus no longer prefixed with the word gawai, e.g. nimang benih in the case of Gawai Benih, ngalihka tanah, ngemali umai by a dukun (healer) for minor or intermediate damage of paddy farm instead of a full-scale Gawai Ngemali Umai, matah and ngambi sempeli.

The rice planting stages start from manggol (ritual initial clearing to seek good omen using a birdstick (tambak burong), nebas (clearing undergrowth), nebang (felling trees), ngerangkaika reban (drying out trees), nunu (burning), ngebak and nugal (clearing unburnt trees and dibbling), mantun (weeding), ninjau belayan (surveying the paddy growth), ngitang tali buru (hanging the protective rope), nekok/matah (first harvesting), ngetau (harvesting), {{lang|iba|nungku} (separating rice grains), basimpan (rice keeping) and nanam taya ba jerami/nempalai kasai (cotton planting).

With the coming of rubber and pepper planting, the Ibans have adapted the Gawai Ngemali Umai (Paddy Farm Healing Festival) and Gawai Batu (Whetstone Festival) to hold Gawai Getah (Rubber Festival) to sharpen the tapping knives and Gawai Lada (Pepper Festival) to avoid diseases and pests associated with pepper planting respectively.[11]

War ritual festivals

The next most important activity among the Iban in the past is headhunting (ngayau) in enemy country. Hence, the war-related festivals is held in honour of the war god, Sengalang Burong (Hawk the Bird) which is manifested as the brahminy kite. These festivals are collectively called Gawai Burong (Bird Festival) in the Saribas/Skrang region or Gawai Amat (Proper Festival) in the Mujong region or Gawai Asal (Original Festival) in the Baleh region. Each set of festivals has a number of successive stages to be initiated by a notable man of prowess from time to time and hosted by individual longhouses. It originally honors warriors, but during more peaceful times has evolved into a wellness or fortune seeking ceremony.

The rules regarding headhunting and skull-related rites are as follows:

- If a warrior got only 3 human skulls, he can hold enchaboh arong to cleanse and strengthen his souls against bad elements.

- If he got more than 3 human skulls, he can hold naku antu pala to parade and praise his trophy heads by the women.

- If he got 7 human skulls, he can hang a bengkong (circle made of rattan or randau).

- If he got one bengkong, he can become a raid leader attacking one longhouse at a time.

- If he got 3 bengkong, he can become a war leader and hold a gawai burung (bird festival) befitting his accomplishments where his human skulls are paraded, chanted for, and respected.

- If he does not hold a gawai burung, he can hold a gawai kenyalang berani (brave hornbill festival) instead.

- After praising the hornbill (nimang kenyalang) statue, he can parade and praise it (naku kenyalang) along the longhouse gallery and among the audience.

Bird Festival

Gawai Burong which is mainly celebrated in the Saribas and Skrang region comprises nine ascending stages as follows:[12]

- Gawai Kalingkang (munti/payan pole) - pengap until ngiga tanah

- Gawai Sandong (betung/pinang trunk)- pengap from ngamboh until manggul

- Gawai Sawi (sawai/rian pole) - pengap from nebang, nunu to ngerara ibun

- Gawai Salangking - selangking with a bungkong tajau baru - pengap until nyulap

- Gawai Mulong Merangau (Weeping Palm) or Lemba Bumbun (durian tree trunk cleverly carved like an old sago palm tree after all of its fruits has fallen to the ground - pengap until nugal

- Gawai Gajah Meram (Brooding Elephant) with Besandau Liau (a strong tree trunk with branches decorated with skulls and isang leaves)- pengap until mantun

- Gawai Meligai (Upper Palace) (decorated strong wood pole) - pengap until nyembui

- Gawai Ranyai (Tree of life) or Mudur Ruruh (the pole is made up of a bunch of warriors’s spears) - pengap until basimpan

- Gawai Gerasi Papa (Demon Huntman) - the house where this gawai is held is abandoned because the inhabitants have to transfer to a new house.

Each celebrant-to-be will decide which stage fits his life achievement or success so far.

Hornbill Festival

Alternatively, the Iban can choose to celebrate another type of bravery-related rite i.e. a rhinoceros hornbill festival (gawai kenyalang).

Proper Festival

In the Baleh region, the Iban there celebrates a slightly different set of Gawai Amat (Proper Festival) as listed by Masing but certainly for similar purposes:[13]

- Gawai Tresang Mansau (a red bamboo pole receptacle)

- Gawai Kalingkang (a bamboo pole receptacle with a pan made of bamboo)

- Gawai Ijok Pumpong (decapitating of gamuti palm ritual)

- Gawai Tangga Raja (notched-ladder of wealth)

- Gawai Kayu Raya (tree of wealth ritual)

- Gawai Kenyalang (hornbill ritual)

- Gawai Nangga Langit (notched-ladder to the sky)

- Gawai Tangga Ari (notched-ladder of day)

Each celebrant will choose which level fits his lifetime achievement as the purpose of the celebration.

There are nine levels of the timang inchantation length with their respective end timing as follows:

- Ngerara rumah (start of timang to discovery of Lang's absence)

- Ngua (nursing the trophy head) - Afternoon second day

- Nyingka (end of forging) - Later afternoon third day

- Bedua antara (dividing the land) - Afternoon fourth day

- Nyulap (first rite of planting) - Morning fifth day

- Ninjau balayan (surveying the padi) - Morning fifth day

- Nekok (first rite of harvesting) - Afternoon fifth day

- Nyimpan padi (storing the padi) - Afternoon fifth day

- Nempalai kasai (planting of cotton) - Morning seventh day

Original Festival

Besides that, there is another list of gawai asal (original gawai) of Iban living the upper Batang Rajang with eight successive stages as per Saleh:[14]

- Gawai Tresang Mansau

- Gawai Kalingkang

- Gawai Ijok Pumpong

- Gawai Sempuyung Mata Ari (a split bamboo cone to focus the sun ray into)

- Gawai Lemba Bumbun (Lemba split leaves which represent taken enemy's hairs)

- Gawai Kenyalang

- Gawai Sandung Liau (a wooden pole with a headhunting boat head statue (udu prau)

- Gawai Mapal Tunggul (Decapitating tree stump with erected three poles in series)

For all three groups of war-related festival above, as the stage of the celebration ascends the list, the level of the timang incantation also increases, following the paddy farming stages with the first stage normally ends up to ngua (nursing) level after which gods will presents gifts in the forms of charms or medicines which help or eases the life building activities of the festival host and fellow celebrants.

Fortune ritual festivals

Seeking wealth and prosperity is another important activity of the Iban. Therefore, the fourth category of festivals is fortune-related festivals which include Gawai Pangkong Tiang (House Main Post Striking Festival) or Gawai Tuah with three successive stages (Luck Seeking, Luck Welcoming and Luck Growing). Some Iban people call Gawai Pangkong Tiang as Gawai Niat (Intention Festival) or Gawai Diri (Rising up Festival).

Procreation ritual festivals

Furthermore, the Iban love to bear and raise many children to continue their descendancy (peturun), as a means to acquire more land and wealth and perhaps to multiply in numbers as a natural defence against enemy tribes. So comes the fifth category of festival which is procreation-related i.e. Gawai Melah Pinang (River Turtle Festival) that is held for daughters to announce that they are ready for marriage and to call for suitable suitors. The wedding ceremony is called Melah Pinang (Areca beetle nut splitting) which is celebrated with much fanfare and ritual. Here the God invoked is Selampandai for fertility and procreation purposes to bear many children. In addition, if an Iban married couple could not bear any child after some years of marriage, they can decide to adopt via a Gawai Bairu-Iru (Adoption Festival) to declare that they have adopted someone which shall have the same rights as their own born child. Furthermore, Gawai Batimbang (Manutrition Festival) can be held to free ulun slaves (war captives) or serfs (debtors) to adopt them as children or siblings or relatives of their masters.

Health ritual festivals

The Iban pay great attention to their health and well-being to have a long life (gayu). So the sixth category of festivals is health-related festivals which are Gawai Sakit (Sickness Festival), Gawai Betawai (Name Changing Festival), Besugi Sakit (Healing by Keling) and Barenong Sakit (Healing by Menjaya). Before employing these healing festivals, there are various types of pelian (healing ceremony) by a manang (traditional healer), pucau (short prayers) and begama (touching) by a dukun (medicinal healer) to be tried first. A candidate will become a manang (shaman) after an official ceremony called Gawai Babangun (Manang-Officiating Festival).

Death ritual festivals

The seventh category of festivals by the Iban is related to death which is called the Spirit festival for the dead (Gawai Antu) or Gawai Rugan (Dead Soul Altar Festival) or Gawai Sungkop (Tomb Festival) in the Saribas/Skrang region or Gawai Ngelumbong (Entombment Festival) in the Baleh region. This festival is used to be held once every 10 to 30 years per longhouse. This festival is the last honouring event in a series of morturial rites from nyengai antu/rabat (death vigil), nganjong antu (burial), baserara bungai (soul separation) and ngetas ulit (mourning termination). During this festival, the dead souls or spirits are invited to attend. A warrior is appointed to drink the ai garong (believed to be the lipid liquid from the dead body) as symbolized using tuak kept in a short bamboo cylinder placed inside a beautifully woven basket called garong hung on the erected ranyai tree. Another junior warriors may drink the ai jalong (put in several ceremonial cups) which is chanted for the whole night. The chanting is to narrate the invitation and coming of souls from the land of the dead (sebayan) led by their king by the name of Raja Niram. Among the entourage are the Iban famous warriors in the region who have passed away. So, the ai jalong drinking ceremony is performed in memory of the famous warriors. Before drinking the two sacred wines, the chanting bard will ask the warriors of their praisenames which they declare to the audience, which indicate the achievements of the warriors and are often followed by war cries and standing ovations. Only warriors who ever obtain enemy heads are permitted to drink both sacred wines. A sacred hut is made for each dead and erected over their grave on the following day.

Weaving ritual festivals

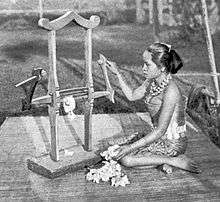

While the Iban man strives to be a successful in headhunting and wealth acquisition, the Iban women aims to be skillful in weaving. For women involved in weaving, their ritual festival is called Gawai Ngar (Cotton-Dyeing Festival). This can perhaps be considered the third category of festivals among the Iban. Pua Kumbu, the Iban traditional hand-woven cloth and custom, is used for both conventional and ceremonial uses in many occasions. There are various types of buah (motives or patterns) of pua kumbu which can be for ritual purposes or normal uses. Both female and male Iban will be graded according to their own personal accomplishments in their lifetime during the rite of ngambi entabalu (widow/widower fee taking).

Dream Festival

There is an emerging category of life-building gawai called dream festivals such as Gawai Lesong (Rice Mortar Festival) and Gawai Tangga (Notched Ladder Festival) and some newly innovated variants of the gawai proper as a result of dream by a person or several individuals. These are popular among the Iban in the upper Rajang region. It appears that the Iban people in this region distinguishes gawai asal (original/customary/traditional festival) from gawai mimpi (dream festival).

The original festival consists of the nine successive and ascending stages of major celebrations as listed by Dr. Robert Menua of Tun Jugah Foundation during an individual Iban man life as if he ascends the longhouse notched ladder rungs. This category of original festival can be celebrated by any Iban if it is deemed fit to do so as he ages during his lifetime, even without any dream.

The Iban will hold a dream festival when told to do so in a dream which will instruct the type and sometimes even the procedure of the festival to be held and thus it is fittingly coined as dream festival. Some variants of the gawai lesong (mortar festival) and gawai tangga (ladder festival) were inspired by dreams as mentioned in Dr. James Masing's PhD thesis so these can actually be considered as dream festival. However, these are called gawai amat (proper/real festival) as the full, elaborate and complex procedure of an Iban festival is strictly followed and implemented during its celebration. A good example to accompany this explanation is the hornbill festival which was held not only as an original festival but also as a dream festival with variations in its procedure of celebration.

Several types of Iban festivals originate from its own epic stories like the hornbill festival from the story of Keling and Laja of Panggau making a hornbill statue for their resptive maidens Kumang and Lulong whom they courted for their famous wives from Gelong while the Gawai Kayu Raya (Massive Tree Festival) also originates from Keling's adventure to fetch the massive tree from overseas that can bear many types of nutritional fruits as if it is a ranyai (tree of life).

Intermediate ritual rites

For simplicity and cost savings, some of the gawai have been relegated into the medium category of propitiation called gawa such as Gawai Tuah into Nimang Tuah, Gawai Benih into Nimang Benih and Gawa Beintu-intu into their respective nimang category wherein the key activity is the timang inchantation by the bards. Gawai Matah can be relegated into a minor rite simply called matah. The first dibbling (nugal) session is normally preceded by a miring offering ceremony of medium size with kibong padi (paddy's net) is erected with three flags. The paddy's net is erected by splitting a bamboo trunk into four pieces along its length with their tips inserted into the groud soil. Underneath the paddy's net, all the paddy seeds in baskets or gunny sacks are kept before being distributed by a line of ladies into dibbled holes by a line men in front.

With headhunting banned and with the advance of Christianity, only some lower ranking ritual festivals are often celebrated by the Iban today such as Sandau Ari (Mid-Day Rite), Gawai Kalingkang (Bamboo Receptacle Festival), Gawai Batu (Whetstone Festival), Gawai Tuah (Fortune Festival) and Gawai Antu (Festival for the Dead Relatives) which can be celebrated without the timang jalong (ceremonial cup chanting) which reduces its size and cost.

It is common that all those festivals are to be celebrated after the rice harvesting completion which is normally by the end of May during which rice is plenty for holding feasts along with poultry like pigs, chickens, fish from rivers and jungle meats like deer etc. Therefore, it is fitting to call this festive season among Dayak collectively as the Gawai Dayak festival which is celebrated every year on 1 June, at the end of the harvest season, to worship the Lord Sempulang Gana and other gods. On this day, the Iban get together to celebrate, often visiting each other.

Culture and customs

Adat Iban or customary law

Among the main sections of customary adat of the Iban Dayaks according to Benedict Sandin which are used to maintain order and keep peace are as follows:[15]

- Adat berumah (house building rule)

- Adat melah pinang, butang ngau sarak (marriage, adultery and divorce rule)

- Adat beranak (child bearing and raising rule)

- Adat bumai and beguna tanah (agricultural and land use rule)

- Adat ngayau (headhunting rule)

- Adat ngasu, berikan, ngembuah and napang manyi (hunting, fishing, fruit and honey collection rule)

- Adat tebalu, ngetas ulit ngau beserarak bungai (widow/widower, mourning and soul separation rule)

- Adat begawai (festival rule)

- Adat idup di rumah panjai (order of life in the longhouse rule)

- Adat betenun, main lama, kajat ngau taboh (weaving, past times, dance and music rule)

- Adat beburong, bemimpi ngau becenaga ati babi (bird and animal omen, dream and pig liver rule)

- Adat belelang tauka bejalai (journey or sojourn rule)

Tuak (rice wine)

.jpg)

Tuak is an Iban wine traditionally made from cooked glutinous rice (asi pulut) mixed with home-made yeast (chiping/ragi) for fermentation. It used to serve guests, especially as a welcoming drink when entering a longhouse. Nowadays, there are various kinds of tuak, made with rice alternatives such as sugar cane, ginger and corn. However, these raw materials are rarely used unless available in large quantities. Tuak and other types of drinks (both alcohol and non-alcoholic) can be served on several rounds in a ceremony called nyibur temuai (serving drinks to guests) as ai aus (thirst quenching drink), ai basu kaki foot washing drink), ai basa (respect drink) and ai untong (profit drink). Another type of a stronger alcoholic drink is called langkau, which contains a higher alcohol content because it is actually made of tuak which has been distilled over fire to boil off the alcohol, cooled and collected into containers.

Cuisine

The Iban plant at least two types of rice paddy in every farming cycle — normal rice and glutinous rice. Normal rice is consumed as a staple diet along with dishes. Glutinous rice is eaten as a staple diet and cooked up a lot during celebrations as rice cakes or rice wine.

Pansoh or lulun is a dish of rice or other food cooked in bamboo cylindrical sections (ruas) with one top end cut open to insert food while the bottom end remains closed and uncut to act as a container. A middle aged bamboo tree is normally chosen because its wall still contain water compared to the old, matured bamboo tree which is dryer and thus get burnt by fire more readily. The bamboo also imparts the famous and addicting, special bamboo taste or flavour to the cooked food or rice. Glutinous rice is often cooked in bamboo for routine diet or during celebrations. It is believed in the old days, bamboo cylinders were used to cook food in the absence of metal pots.

Kasam is preserved meat or fish. In the absence of refrigerators, often jungle meats from wild games or river fish are preserved by cutting them into small pieces and mixed with salt before being placed into a ceramic jar or glass jar nowadays. Therefore, ceramic jars were precious in the old days as food, tuak or general containers. The preserved meats can last for at least several months.

Another way of preserving food is by drying the meat or fish over slow fire to release most of the fluid out. This dried food can last for a month or so. Often the food is placed on the "para" (platform) over kitchen's fire. This dried meat, called salai, can later be cooked again or mixing it with other wild vegetables as a soup.

There are many wild vegetables which the Iban collect from the jungle or forest. Among them are fern such as kemiding, paku ikan and paku keru. A favourite vegetable during major celebrations is shoot of wild palms such as pantu, sago (mulong) or aping which provides a large amount of vegetable to a large crowd. Bamboo shoots (tubu) are another favourite vegetable. Iban women who are skillful at gathering these vegetables are called indu paku, indu tubu.

Music

Iban music is percussion-oriented. The Iban have a musical heritage consisting of various types of agung ensembles - percussion ensembles composed of large hanging, suspended or held, bossed/knobbed gongs which act as drones without any accompanying melodic instrument. The typical Iban agung ensemble will include a set of engkerumungs (small agungs arranged together side by side and played like a xylophone), a tawak (the so-called "bass"), a bendai (which acts as a snare) and also a set of ketebung or bedup (a single sided drum/percussion instrument).

There are various kinds of taboh (music), depending the purpose and types of ngajat, like alun lundai. The gendang can be played in some distinctive types corresponding to the purpose and type of each ceremony with the most popular ones are called gendang rayah and gendang pampat.

Sape is originally a traditional music by Orang Ulu (Kayan, Kenyah and Kelabit). Nowadays, both the Iban as well as the Orang Ulu Kayan, Kenyah and Kelabit play an instrument resembling the guitar called the sape. Datun Jalut and nganjak lansan are the most common traditional dances performed in accordance with a sape tune. The Sape (instrument) is the official musical instrument for the Malaysian state of Sarawak. It is played similarly to the way rock guitarists play guitar solos, albeit a little slower, but not as slow as blues.[16][17] One example of Iban traditional music is the taboh.

The Ibans perform a unique traditional dance called the ngajat, kajat or ajat. The word kajat or ajat originates from the word engkajat which means "jumping on the spot". The Ibans perform the many kinds of dances accompanied by the music of gongs and drums. These dances include the ngajat, bepencha, bekuntau, main kerichap, and main chekak.

The ajat dance is attributed to a spiritual being, Batu Lichin, Bujang Indang Lengain, who brought it to the Iban many generations ago. Another story says that the ajat dance originates from warriors who happily dance e.g. at the head of their war-boats after successfully obtain trophy heads during headhunting raids and the practice is continued until today. Today there are many kinds of ajat dances performed by the Ibans.

It serves many purposes depending on the occasion. During Gawai, it is used to entertain the people who once enjoyed ngajats as a form of entertainment. Iban men and women have different styles of ngajat. The ngajat involves graceful movements of the body, hands and legs, shouts or war-cries and sometimes precise body-turning movements. The dancers sometimes use hand-held weapons. The ngajat for men is more aggressive and depicts a man going to war, or a hornbill walking (as a respect to the Iban god of war, "Sengalang Burong"). The women's form of ngajat consists of soft, graceful movements with very precise body turns and sometimes uses the traditional pua kumbu or handkerchief. Each ngajat is accompanied by the taboh.

Types of Iban Ngajat Dance

There are about four categories of Iban traditional ngajat dance according to their respective functional purpose as follows:[18]

Showmanship dance

- Ngajat ngalu temuai (welcoming dance) by a group of females

- Ngajat indu (female dance)

- Ngajat pua kumbu (a female dance with a woven blanket which is most likely woven by herself)

- Ngajat lelaki (male dance)

- Ngajat lesung (rice mortar dance)

- Ngajat pinggai ngau kerubong strum (dance with one rice ceramic plate held on each palm while tapping the plates with an empty bullet shell inserted into the middle fingers of both hands)

- Ngajat bujang berani ngena terabai ngau ilang (warrior dance with full costume, a shield and sword)

- Ngajat bebunoh (hand combat dance normally between two male dancers)

- Ngajat nanka kuta (fort defence dance)

- Ngajat semain laki ngau indu (dance by a group of men and ladies)

- Ngajat niti papan (dance by a group of men and ladies on a raised up wooden plank)

- Ngajat atas tawak (dance on top of gongs by ladies with gentlemen in the background)

- Ngajat ngalu pengabang (dance by a man with several ladies behind who lead the procession of guests during festivals)

These types of dance can be performed either on an open space or around the pun ranyai which is the tree of life

Ritual dance

- Ngajat panggau libau as a group of men with a sword and isang leaves.

- Ngerandang jalai (pathway-clearing), ngelalau jalai (pathway fencing)

- Berayah pupu buah rumah (longhouse contribution collection)

- Berayah ngelilingi pun sabang ngau tiang chandi gawai (dancing around the festival ritual pole)

- Naku antu pala (welcoming human heads)

- Naku pentik kenyalang (welcoming hornbill statue)

Comedial dance

- Ngajat kera (monkey dance)

- Ngajat muar kesa(stinging Ants' nest collection)

- Ngajat matak wi (rattan pulling dance)

- Ngajat nyumpit (blowpiping dance)

- Ngajat bekayuh (paddling dance)

- Ngajat mabuk (drunk dance)

- Ngajat bunyan baka lari maya ngasu (running scared dance e.g. scared of animals while hunting)[19]

- Ngajat ngelusu berapi, beribunka anak ngau nutok (lazy woman dance)

- Ngajat pama (frog dance)

- Ngajat gerasi tunsang (upside down huntsman dance)

- Ngajat tempurung nyor (coconut shell dance)

- Ngajat turun tupai (squirrel going down dance)

- Ngajat jelu bukai (other animal mimicking dance)

Self-defence dance

- Bekuntau (self-defence dance)

- Bepenca (martial art dance)

- Main kerichap

- Main chekak

According to one Iban writer,[20] when a warrior performs the ajat bebunoh dance with the music of a gendang panjai orchestra, he does it as if he is fighting against an enemy. With occasional shouts he raises his shield with one arm and swings his ilang knife with his other arm as he moves towards the enemy. While he moves forward he is careful with the steps of his feet to guard them from being cut by his foe. The tempo of his action is very fast with his knife and shield gleaming up and down as he dances.

The man dance has various unique moves such as minta ampun (apologising to guests first), showing skills of playing with the sword and the shield, biting the sword in the mouth for affirming his strength, balancing the sword over his shoulder while still dancing, engkajat (fast foot movement to distract the attention of the enemy), running forward with the sword pointed towards the enemy and shouting war cries to strike the enemy and finally the glory of holding the enemy's freshly chopped head. The enemy head may be symbolised by a coconut which is hung beforehand on the tree of life and the ending move is apologising to the guests again.

The performance of ajat semain is done in slower tempo and with graceful movements. The dancer softens his body, arms and hands as he swings forward and backward. When he bends his body the swinging of his hands is very soft. The performance of the ngajat nanggong lesong dance is more or less like the ajat semain dance. Only when the dancer bites and raises the heavy wooden mortar (lesong) with his teeth and place it again carefully on the floor, does he use extraordinary skill.

When the dancers take the floor to dance, the musicians beat two dumbak drums, a bendai gong, a set of seven small gongs (engkerumong) and a large tawak gong. The music for the performance of ajat bebunoh dance is quicker in tempo than the music for the ajat semain and ajat nanggong lesong dances, as in the dance itself.

Types of Iban gendang music

As from time immemorial, the people of the longhouse have been skilled in playing all kinds of gendang music. Another important music performed by the Ibans is called gendang rayah. It is played only for religious festivals with the following instruments:

- The music from a first bendai gong is called pampat

- The music from a second bendai gong is called kaul

- The music from a third bendai gong is called kura

- As the three bendai gongs sound together, then a first tawak gong is beaten and is added to by the beating of another tawak gong to make the music.

Last but not least, is the music played using the katebong drums by one or up to eleven drummers. These drums are long. Its cylinder is made from strong wood, such as tapang or mengeris, and one of its ends is covered with the skins of monkeys and mousedeer or the skin of a monitor lizard. The major types of drum music are known as follows:

- Gendang Bebandong

- Gendang Lanjan

- Gendang Enjun Batang

- Gendang Tama Pechal

- Gendang Pampat

- Gendang Tama Lubang

- Gendang Tinggang Batang

- Singkam Nggam

All these types are played by drummers on the open air verandas during the celebration of the Gawai Burong festival. The Singkam Nggam music is accompanied by the quick beating of beliong adzes. After each of these types has been played, the drummers beat another music called sambi sanjan, which is followed by still another called tempap tambak pechal. To end the orchestral performance the music of gendang bebandong is again beaten.

The ordinary types of music beaten by drummers for pleasure are as follows:

- Gendang Dumbang

- Gendang Ngang

- Gendang Ringka

- Gendang Enjun Batang

- Kechendai Inggap Diatap

- Gendang Kanto

When a Gawai Manang or bebangun festival is held for a layman to be consecrated as a manang (shaman), the following music must be beaten on the ketebong drums at the open veranda (tanju) of the longhouse of the initiate:

- Gendang Dudok

- Gendang Rueh

- Gendang Kelakendai

- Gendang Tari

- Gendang Naik

- Gendang Po Umboi

- Gendang Sembayan

- Gendang Layar

- Gendang Bebandong

- Gendang Nyereman

Gendang Bebandong also must be beaten when a manang dies and is beaten again when his coffin is lowered from the open air verandah (tanju) to the ground below on its way to the cemetery for burial.

Iban musical instruments

In addition to playing music on the above-mentioned instruments, Iban men enjoy the music of the following instruments:

- Engkerurai (bagpipe)

- Kesuling (flute)

- Ruding (Jew's harp)

- Rebab (guitar with two strings)

- Balikan (guitar with 3 strings)

- Belula (violin)

- Engkeratong (harp)

The women, especially the maidens, are fond of playing the Jew's harp while conversing with their visiting lovers at night, with the tunes from the ruding Jew's harp, the girls and their boyfriends relate how much they love each other. In past generations, there were very few Iban men and women who did not know how to converse with each other by using the ruding Jew's harp. Today very few younger people know how to play this instrument and the art is rapidly dying out.

Traditional costumes

The ngajat dancers will usually wear their traditional costumes.

The male costume consists of the following:

- Sirat (loincloth)

- Baju burong (bird shirt)

- Baju buri (bead shirt)

- Baju gagong (animal skin cloth)

- Engkerimok

- Unus lebus

- Simpai rangki

- Tumpa bala (five on both sides)

- Labong pakau or lelanjang (headgear)

The female costume includes:[21]

- Kain batating (petticoat with decorated bells at the bottom end)

- Rawai tinggi (high corset with rattan coils inserted with small brass rings)

- Sugu tinggi (high headgear)

- Marik empang (beaded chain)

- Selampai (long scalp)

- Lampit (silver belt)

- Tumpak (armlet)

- Gelang kaki (anklet)

- Antin pirak (silver stud earrings)

- Buah pauh purse

Rhythms of taboh music

One Iban writer briefly describes the rhythms of taboh music played the Iban's brass band orchestra[22] which translates as "The number of musicians to play taboh music is four ie one playing the bebendai (small gong) which is beaten first of all to determine the rhythm of the taboh, responded to by the gendang or dedumbak drum, followed by the tawak (big gong) and finalized by the engkerumong set."

To the laymen's ears, the rhythms of taboh music for ngajat dance is only two i.e. fast or slow but actually it has four types namely Ayun Lundai (slow swing), Ai Anyut (flowing water), Sinu Ngenang (sad remembrance) and Tanjak Ai (against the water flow). The first three taboh types are slow to accompany the ajat semain (group dance), ajat iring (accompanying dance) and ajat kelulu (comedial dance). The fourth rhythm of taboh is fast which is suitable for the ajat bebunoh (killing dance). Other rhythms of taboh music are tinggang punggung for ngambi indu (taking the bride for wedding) and taboh rayah (rayah music) for ngerandang and ngelalau jalai (pathway clearing and fencing dance).

Handicrafts

Carvings

Traditional carvings (ukir) include hornbill effigy carving, terabai shield, engkeramba (ghost statue), knife stilt normally made of deer horn, knife scabbard, decorative carving on the metal blade itself during ngamboh blacksmithing e.g. butoh kunding, and frightening mask (India guru).

Another related category is designing motives either by engraving or drawing with paints such wooden planks, walls or house posts.

Even the traditional coffins will be beautifully decorated using both carving and ukir-painting.

Types of Iban pantang or kalingai (tattoo)

The Ibans like to tattoo themselves all over their body. There are motifs for each part of the human body. The purposes are to protect the tattoo bearers or to signify certain events in their life.

Some motifs are based on marine lives such as crayfish (rengguang), prawn (undang) and crab (ketam) while other motifs are based on dangerous creatures like cobra (tedong), scorpion (kala), ghost dog (pasun) and dragon (naga). Other normal motifs include items which Iban travellers meet during their journey such as aeroplane on the chest.

Some Ibans call this art of tattoing as kalingai or ukir.

To signify that an individual has killed an enemy (udah bedengah), he is entitled to tattoo his throat (engkatak) or his upper-side fingers (tegulun).

Some traditional Iban do have piercings on the penis (called palang) or ear lobes.

Weaving

Woven products are known as betenun. Several types of woven blankets made by the Ibans are pua kumbu, pua ikat, kain karap and kain sungkit.[23] Using weaving, the Iban makes blankets, bird shirt (baju burong), kain kebat, kain betating and selampai. Weaving is the women's warpath while kayau (headhunting) is the men's warpath.

The pua kumbu do have conventional or ritual motives depending on the purpose of weaving it. Those who finish the weaving lessons are called tembu kayu (finish the wood) [[24]]. Among well known ritual motives are Gajah Meram (Brodding Elephant), Tiang Sanding (Ritual Pole), Meligai (Shrine) and Tiang Ranyai.[25]

Types of Iban plaitings or beranyam

The Iban call this skill pandai beranyam (skilful in plaiting) various items namely mats (tikai), baskets and hats.

The Ibans weave mats of numerous types namely tikai anyam dua tauka tiga, tikai bebuah (motived mat),[26] tikai lampit made of rattan and tikai peradani made of rattan and tekalong bark.

Materials to make mats are beban to make the normal mat or the patterned mat, rattan to make tikai rotan, lampit when the rattan splits sewn using a thread or peradani when criss-crossed with the tekalong bark, senggang to make perampan used for drying and daun biruto make a normal tikai or kajang (canvas) which is very light when dry.

The names of Iban baskets are bakak (medium-sized container for transferring, lifting or medium-term storage), singtong (container for raping ripen paddy worn at the waist), raga (small container), tubang (cylindrical backpack), lanji (tall cylindrical backpack) and probably selabit (almost rectangular shaped backpack).

Another category of plaiting which are normally carried out by men is to make fish traps called bubu gali, bubu dudok, engsegah and abau using betong bamaboo splits except bubu dudok is made from ridan which can be bent without breaking.

The Iban also makes special baskets called garong for the dead during Gawai Antu with numerous feet to denote the rank and status of the deceased which indicates his ultimate achievement during his lifetime.

The Iban also make pukat (rectangular net) and jala (conical net) after nylon have ropes become available.

Types of Iban hunting apparatus

These include making panjuk (rope and spring trap), peti (bamboo blade trap) and jarin (deer net). Nowadays, they use shotguns and dogs for animal hunting. Dogs are reared by the Ibans in longhouses especially in the past for hunting (ngasu) purposes and warning of any danger approaching. Shotguns can be bought from the Brooke government. The Ibans make their own blowpipes, and obtain honey from the tapang tree.

The Iban boat or perau making

The Ibans can make their boats. The canoes for normal use is called perau but big war boats are called bangkong or bong which is probably fitted with long paddles and a wind sail made of kajang canvas. It is said that bangkong is used to sail along the sea coasts of northern Borneo or even to travel across the seas e.g. to Singapore.

The Iban blacksmithing or ngamboh

The Ibans make various blades called nyabur, ilang, pedang, duku chandong, duku penebas, lungga (small blade), sangkoh, jerepang, Beirut, and mata lanja sumpit.

Although silversmithing originates from the Embaloh, some Ibans became skilled in this trade to make silverware for body ornaments. The Iban always buy brasswares such tawak (gong), bendai (snare) and engkerumong, tabak (tray) and baku (small box) from other peoples because they do not have the skills of brasssmithing.

The Iban makes their own kacit pinang to split the ereca nuts and pengusok pinang to grind the split pieces of the ereca nut. They also make ketap (finger-held blade) to reap ripen paddy stalks and iluk (hand-held blade) to weed.

Iban traditional possessions

- Head Skull

The Ibans used to regard human skulls (called antu pala) obtained during headhunting raids (ngayau) as their most prized trophy and possession.

- Jar

The Ibans treasure jars which are called benda or tajau which include, pasu, salang-alang, alas, rusa, menaga, ningka, sergiu, pereni and guchi. Possession of these jars mark someone's wealth and any fines may be paid using benda or tajau in the old days and presently used nowadays as part of upah (pay) for bards and shamans.

- Brassware

Iban strive to own a full set of brass musical instruments which comprises a tawak (gong), bendai (snare), engkurumong (small gong) and bedup (drum).

- Paddy

Getting a lot of paddy used to be highly regarded and perhaps an indication of wealth.

- Shaman and bard

Having a manang shaman and lemambang bards is also regarded necessary possession with the Iban riverine community. This practice used to be to have one set per river tributary, if not per a longhouse. Nowadays, obtaining educational degrees is foremost in the Iban minds e.g. the target is to have a degree graduate per family bilek within a longhouse.

- Land

The Iban aims to own land as much as possible via berumpang menua (jungle clearing) before when fresh jungles were still available in abundance. Therefore the Ibans were willing to migrate to new areas. Before the arrival of James Brooke, the Iban had migrated from Kapuas to Saribas and Skrang, Batang Ai, Sadong, Samarahan, Katibas, Kapit and Baleh in order to own fress tracks of jungles among the reasons. Some Ibans participated in Brooke-led punitive expeditions against their own countrymen in exchange for areas to migrate to.

- Longhouse

Many Iban still believes in the necessity and importance of living in longhouses rather single-houses within a kampong village e.g. during gatherings, meetings, farming and festivals.

- Defence weaponry

Iban males will have a set of war weaponry which include a knife, a terabai shield, a blowpipe, a sangkoh spear and a baju gagong (tough animal skin shirt). In addition, the Iban will look for charms called pengaroh, empelias, pengerabun, etc.

- Longboat

Each Iban family will own at least one long boat for transportation along rivers.

Agriculture and economy

Ibans plant rice paddies once a year with twenty seven stages.[27][28] Other crops planted include ensabi, cucumber (rampu amat and rampu betu), brinjal, corn, lingkau, and cotton before commercial threads are sold in the market.

For cash, the Ibans find jungle produce for sale in the market. Later, they plant rubber, pepper and cocoa. Nowadays, many Ibans work in the town areas to seek employment or involve in trade or business.

Military

Two highly decorated Iban Dayak soldiers from Sarawak in Malaysia are Temenggung Datuk Kanang anak Langkau (awarded Seri Pahlawan Gagah Perkasa)[29] and Awang anak Raweng of Skrang (awarded a George Cross).[30][31] So far, only one Dayak has reached the rank of general in the military, Brigadier-General Stephen Mundaw in the Malaysian Army, who was promoted on 1 November 2010.[32]

Malaysia’s most decorated war hero is Kanang Anak Langkau due to his military services helping to liberate Malaya (and later Malaysia) from the communists. Among all the heroes were 21 holders of Panglima Gagah Berani (PGB) which is the bravery medal with 16 survivors. Of the total, there are 14 Ibans, two Chinese army officers, one Bidayuh, one Kayan and one Malay. But the majorities in the Armed Forces are Malays, according to a book – Crimson Tide over Borneo. The youngest of the PGB holder is ASP Wilfred Gomez of the Police Force.

There were six holders of Sri Pahlawan (SP) Gagah Perkasa (the Gallantry Award) from Sarawak, and with the death of Kanang Anak Langkau, there is one SP holder in the person of Sgt. Ngalinuh (an Orang Ulu).

Iban calendar

The Iban calendar is one month ahead of the Gregorian calendar as follows:

- First month - called Bulan Pangka Di Labu, corresponding to December, and is when rice paddies start to ripen.

- Second month - called Bulan Empalai Rubai, corresponding to January.

- Third month - called Bulan Emperaga/Empikap, corresponding to February when harvesting starts.

- Fourth month - called Bulan Lepa/Lelang, corresponding to March when expedition, sojourn or journey begins.

- Fifth month - called Bulan Turun Panggul, corresponding to April when farming (manggul) is initiated.

- Sixth month - called Bulan Sandih Tundan, corresponding to May during which clearing of undergrowth commences.

- Seventh month - simply called Bulan tujuh, corresponding to June during felling and ngereda (chopping all branches of felled big trees so that fire can raze upon them easily) is carried out.

- Eighth month - called Bulan Belanggang Reban, corresponding to July which is the drying season.

- Ninth month - called Bulan Kelebun, corresponding to August when burning and dibbling start.

- Tenth month - called Bulan Labuh Benih, corresponding to September when dibbling continues.

- Eleventh month - called Bulan Gantung Senduk, corresponding to October when most Iban finish planting rice paddies.

- Twelfth month - called Bulan Chechanguk, corresponding to November when weeding is completed.

In popular culture

- The episode "Into the Jungle" from Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations included the appearance of Itam, a former Sarawak Ranger and one of the Iban people's last members with the entegulun (Iban traditional hand tattoos) signifying his taking of an enemy’s head.

- The Iban were featured on an episode of Worlds Apart, a National Geographic Channel television series.

- The film The Sleeping Dictionary features Selima (Jessica Alba), an Anglo-Iban girl who falls in love with John Truscott (Hugh Dancy). The movie was filmed primarily in Sarawak, Malaysia.

- Malaysian singer Noraniza Idris recorded "Ngajat Tampi" in 2000 and followed by "Tandang Bermadah" in 2002, which are based on traditional Iban music compositions. Both songs reached popularity in Malaysia and neighbourhood countries.

- Chinta Gadis Rimba (or Love of a Forest Maiden), a 1958 film directed by L. Krishnan based on the novel of the same name by Harun Aminurrashid, tells about Iban girl Bintang who goes against the wishes of her parents and runs off to her Malay lover. The film is the first time a full-length feature film has been shot in Sarawak plus the first time an Iban woman has played as a lead character.[33]

- "Bejalai" is a 1987 film directed by Stephen Teo, notable for being the first film to be made in the Iban language and also the first Malaysian film to be selected for the Berlin International Film Festival. The film is an experimental feature about the custom among the Iban young men to do a "bejalai" (go on a journey) before attaining maturity.

- In Farewell to the King, a 1969 novel by Pierre Schoendoerffer plus its subsequent 1989 film adaptation, American prisoner-of-war Learoyd escapes a Japanese firing squad into hiding in the wilds of Borneo, where he is adopted by an Iban community.

- In 2007, Malaysian company Maybank produced a wholly Iban-language commercial commemorating Malaysia’s 50th anniversary of independence. The advert, directed by Yasmin Ahmad with help of the Leo Burnett agency, was shot in Bau and Kapit and used an all-Sarawakian cast.[34]

Notable people

- Rentap, rebel leader

- Jugah anak Barieng, second Paramount Chief of the Iban people and the key signatory on behalf of Sarawak to the Malaysia Agreement

- Alexander Nanta Linggi, member of parliament for Kapit and former cabinet minister

- Stephen Kalong Ningkan, the first Chief Minister of Sarawak

- Tawi Sli, the second Chief Minister of Sarawak

- Douglas Uggah Embas, one of the three Deputy Chief Ministers of Sarawak

- James Jemut Masing, one of the three Deputy Chief Ministers of Sarawak

- Stephen Rundi Utom, current member of the Sarawak State Executive Council

- Kanang anak Langkau, National hero of Malaysia

- Joseph Entulu Belaun, Member of the Malaysian Parliament

- Ali Anak Biju, current member of parliament for Saratok federal constituency and state assemblyman for Krian.

- Henry Golding, actor

See also

References

- ↑ "State statistics: Malays edge past Chinese in Sarawak". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Iban of Indonesia". People Groups. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ↑ "Iban of Brunei". People Groups. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ↑ "Borneo trip planner: top five places to visit". News.com.au. 2013-07-21. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ↑ Leo Sutrisno (2015-12-26). "Rumah Betang". Pontianak Post. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ↑ Leka Main: Iban Folk Poetry - An Analysis of Form and Function by Dr Chermaline Usop

- ↑ Ensera Ayor: Epik Rakyat Iban (Penerbit USM) By Noriah Taslim, Chemaline Osu

- ↑ "2010 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia" (PDF) (in Malay and English). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2012. checked: yes. p. 108.

- ↑ Raja Burong by Benedict Sandin

- ↑ Tamara Thiessen (2008). Bradt Travel Guide - Borneo. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 18-416-2252-4.

- ↑ Saribas Ibans' rite of paddy storage by Prof Clifford Santher

- ↑ Gawai Burong by Benedict Sandin

- ↑ https://digitalcollections.anu.edu.au/bitstream/…/Masing_J.%20J._1981.pdf

- ↑ Adat Gawai by Dr. Robert Menua Anak Saleh and Walter Ted Anak Wong

- ↑ Iban Adat and Augury by Bendict Sandin

- ↑ Mercurio, Philip Dominguez (2006). "Traditional Music of the Southern Philippines". PnoyAndTheCity: A center for Kulintang - A home for Pasikings. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ↑ Matusky, Patricia. "An Introduction to the Major Instruments and Forms of Traditional Malay Music." Asian Music Vol 16. No. 2. (Spring-Summer 1985), pp. 121-182.

- ↑ The role of Dayak Cultural Foundation in preserving the Iban traditional ngajat dance by Jerry Hawkin Anak Suting

- ↑ "NGAJAT IBAN". 28 April 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Ajat Enggau Gendang Iban". 22 April 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Leonora, Veeky (28 September 2011). "Kumang Saribas..and this is my story...: Kumang Iban of Various Tribes hence Various Costumes..." Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Ajat ngau Taboh Iban". 1 June 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Pua Kumbu – The Legends Of Weaving". Ibanology. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ "Pua Kumbu – The Legends Of Weaving". 8 April 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Restoring Panggau Libau: a reassessment of engkeramba' in Saribas Iban ritual textiles (pua' kumbu')". 23 April 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ See examples here https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.269499373193118.1073741835.101631109979946&type=3,

- ↑ Iban Agriculture by JD Freeman

- ↑ Report on the Iban by JD Freeman

- ↑ Ma Chee Seng & Daryll Law (2015-08-06). "Remembering Fallen Heroes on Hero Memorial Day". New Sarawak Tribune. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ Rintos Mail & Johnson K Saai (2015-09-06). "Ailing war hero may miss royal audience this year". The Borneo Post. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ "Sarawak (Malaysian) Rangers, Iban Trackers and Border Scouts". Winged Soldiers. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ "Stephen Mundaw becomes first Iban Brigadier General". The Borneo Post. 2010-11-02. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ "Wanted: a jungle belle who knows about love". The Straits Times. 3 September 1956. p. 7. Retrieved 28 March 2017 – via NewspaperSG.

- ↑ coconutice (4 September 2007), Maybank Advert in Iban, retrieved 27 March 2017

Bibliography

- Sir Steven Runciman, The White Rajahs: a history of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946 (1960).

- James Ritchie, The Life Story of Temenggong Koh (1999)

- Benedict Sandin, Gawai Burong: The chants and celebrations of the Iban Bird Festival (1977)

- Greg Verso, Blackboard in Borneo, (1989)

- Renang Anak Ansali, New Generation of Iban, (2000)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iban. |