Safflower

| Safflower | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Carthamus |

| Species: | C. tinctorius |

| Binomial name | |

| Carthamus tinctorius | |

Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) is a highly branched, herbaceous, thistle-like annual plant. It is commercially cultivated for vegetable oil extracted from the seeds. Plants are 30 to 150 cm (12 to 59 in) tall with globular flower heads having yellow, orange, or red flowers. Each branch will usually have from one to five flower heads containing 15 to 20 seeds per head. Safflower is native to arid environments having seasonal rain. It grows a deep taproot which enables it to thrive in such environments.

History

Safflower is one of humanity's oldest crops. Chemical analysis of ancient Egyptian textiles dated to the Twelfth Dynasty identified dyes made from safflower, and garlands made from safflowers were found in the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun.[2] John Chadwick reports that the Greek name for safflower κάρθαμος (kārthamos) occurs many times in Linear B tablets, distinguished into two kinds: a white safflower (ka-na-ko re-u-ka, 'knākos leukā'), which is measured, and red (ka-na-ko e-ru-ta-ra, 'knākos eruthrā') which is weighed. "The explanation is that there are two parts of the plant which can be used; the pale seeds and the red florets."[3]

Production

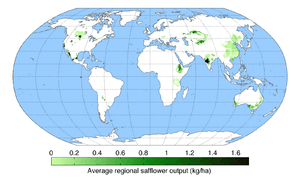

In 2013, global production of safflower seeds was 718,161 tonnes, with Kazakhstan accounting for 24% of the total. Other significant producers were India, the United States, Mexico and Argentina.[4]

Uses

Traditionally, the crop was grown for its seeds, and used for coloring and flavoring foods, in medicines, and making red (carthamin) and yellow dyes, especially before cheaper aniline dyes became available.[2] For the last fifty years or so, the plant has been cultivated mainly for the vegetable oil extracted from its seeds.

Seed oil

Safflower seed oil is flavorless and colorless, and nutritionally similar to sunflower oil. It is used mainly in cosmetics and as a cooking oil, in salad dressing, and for the production of margarine. INCI nomenclature is Carthamus tinctorius.

There are two types of safflower that produce different kinds of oil: one high in monounsaturated fatty acid (oleic acid) and the other high in polyunsaturated fatty acid (linoleic acid). Currently the predominant edible oil market is for the former, which is lower in saturated fats than olive oil. The latter is used in painting in the place of linseed oil, particularly with white paints, as it does not have the yellow tint which linseed oil possesses.

Oils rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, notably linoleic acid, are considered to have some health benefits. One human study compared high-linoleic safflower oil with conjugated linoleic acid, showing that body fat decreased and adiponectin levels increased in obese women consuming safflower oil.[5]

The assumed benefits of linoleic acid in the case of heart disease are less obvious: in one study where high-linoleic safflower oil replaced animal fats in the diets of patients with heart disease, the group receiving safflower oil in place of animal fats had a significantly higher risk of death from all causes, including cardiovascular diseases.[6] In the same study, a meta-analysis of linoleic acid used in intervention clinical trials showed no evidence of cardiovascular benefit. However, a meta-analysis published in 2014 concluded that linoleic acid in people's diet "is inversely associated with CHD risk in a dose-response manner. These data provide support for current recommendations to replace saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat for primary prevention of CHD."[7]

Flower

Safflower flowers are occasionally used in cooking as a cheaper substitute for saffron, sometimes referred to as "bastard saffron".[8]

The dried safflower petals are also used as a herbal tea variety.

In coloring textiles, dried safflower flowers are used as a natural dye source for the orange-red pigment Carthamin.[9] Carthamin is also known, in the dye industry, as Carthamus Red or Natural Red 26.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "Tropicos". Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO. 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 Daniel Zohary, Maria Hopf and Ehud Weiss, Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin, 4th edition (Oxford: University Press, 2012), p. 211

- ↑ John Chadwick, The Mycenaean World (Cambridge: University Press, 1976), p. 120

- ↑ "World production of safflower seeds in 2013; Browse Production/Crops/World". United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Norris, L. E.; Collene, A. L.; Asp, M. L.; Hsu, J. C.; Liu, L. F.; Richardson, J. R.; Li, D; Bell, D; Osei, K; Jackson, R. D.; Belury, M. A. (2009). "Comparison of dietary conjugated linoleic acid with safflower oil on body composition in obese postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (3): 468–476. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27371. PMC 2728639. PMID 19535429.

- ↑ Ramsden, C. E.; Zamora, D.; Leelarthaepin, B.; Majchrzak-Hong, S. F.; Faurot, K. R.; Suchindran, C. M.; Ringel, A.; Davis, J. M.; Hibbeln, J. R. (2013). "Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: Evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis". BMJ. 346: e8707. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8707. PMC 4688426. PMID 23386268.

- ↑ Farvid, Maryam S.; Ding, Ming; Pan, An; Sun, Qi; Chiuve, Stephanie E.; Steffen, Lyn M.; Willett, Walter C.; Hu, Frank B. (2014). "Dietary Linoleic Acid and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies". Circulation. 130: 1568–1578. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010236. PMC 4334131.

- ↑ E.g. "safflower" in Webster's Dictionary, year 1828. E.g. "bastard saffron" in The Herball, or General Historie of Plantes, by John Gerarde, year 1597, pages 1006-1007.

- ↑ Dweck, Anthony C. (ed.) (June 2009), Nature provides huge range of colour possibilities (PDF), Personal Care Magazine, pp. 61–73, retrieved 30 Oct 2012

- ↑ "Carthamus Red". 1997 [1992]. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carthamus tinctorius. |

- Safflower field crops manual, University of Wisconsin, 1992

- The Paulden F. Knowles personal history of safflower germplasm exploration and use, University of California-Davis, Department of Plant Sciences

| Look up safflower in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |