Robert Towns

| Robert Towns | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Robert Towns, by unknown artist | |

| Born | 10 November 1794 |

| Died | 11 April 1873 (aged 78–79) |

| Burial place | Balmain Cemetery |

Robert Towns (10 November 1794 – 11 April 1873) was an Australian merchant, shipowner, pastoralist, politician, whaler, civic leader and founder of Townsville, Queensland.

After a career at sea as a master mariner based in Britain, Towns came to Australia in 1843 as the agent for London merchant Robert Brooks (MP). He also became a merchant in his own right in Sydney with involvement in the sandalwood trade, pelagic whaling and as an importer of sugar and tea and exporter of wool, whale oil, cotton and other commodities. He later became a pastoralist and pioneered the cultivation of cotton in Queensland.

The head office of Robert Towns & Company was in Sydney with branch offices in Melbourne, Brisbane, Dunedin and Townsville.[1] His far flung trading connections saw him do business with merchants in Mauritius, India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), the Philippines, New Zealand, New Caledonia, China, the New Hebrides, California and Chile.

Early life

Towns was born at Longhorsley, Northumberland, England, on 10 November 1794.[2] He was educated at a village school and went to sea at an early age as an apprentice on a North Shields collier. He was a mate by the age of 17, and a master on a brig in the Mediterranean two years later. He made his first voyage to Australia as captain of Boa Vista in 1827.[3] He was a regular trader to Australia by the time he arrived in command of the Brothers (325 tons) in August 1832.[4] In 1838 he took command of Royal Saxon for London merchant, shipowner and banker Robert Brooks (MP).[5] Towns was also part-owner of the vessel. During the First Opium War (1839-1842) he broke the British blockade of Canton and took aboard a cargo of tea "at the highest freight rates yet seen in British private trade."[6] On his return to London he was asked to go to Australia to put in order the affairs of Brooks agent in Sydney, Ranulph Dacre.

Career

New South Wales

Towns reached Port Jackson in March 1843, and took charge of the Sydney agency of Robert Brooks & Co.[7] He was joined by his wife and son the following year. He already had strong ties in Sydney. Apart from almost annual voyages to the colony in the preceding fifteen years, on 28 December 1833 he had married Sophia Wentworth at St Philip's Church, Sydney; the couple honeymooned at Toongabbie at the estate of explorer and politician William Charles Wentworth (Sophia's brother).[8][9]

In 1843 he established Robert Towns & Co., General Merchants, Ship and Commission Agents, at Sydney. An early investment was the purchase of the Elizabeth (174 tons) in 1843.[10] She had been built in 1816 and the purchase of old vessels like her became a feature of his shipowning. In 1855 he took into the partnership (later Sir) Alexander Stuart.[11] By 1857 the firm had made profits of £245,000.[12] Much of this success relied on the ongoing business relationship with Robert Brooks. Brooks made available capital for joint ventures, made advances against Australian exports and provided general financial backing for Robert Towns & Co.

The depressed colonial economy of the early 1840s, and his ready access to credit, allowed Towns to quickly become established as a leading figure in the shipping industry. He purchased eight vessels and also a well-located wharf at Millar's Point, Darling Harbour, that soon became known as Towns' Wharf.[13] The vessels were put to work in the sandalwood trade, as pelagic whalers and as trading vessels. His standing in the Sydney commercial circles saw him invited the join the board of the Bank of New South Wales in 1850.[14] Later in the decade, he became president of the bank.

Towns entry into the sandalwood trade began with a stroke of good fortune. His vessel Elizabeth returned to Sydney on 29 June 1845 from Tanna with 100 tons of sandalwood.[15] It was sent to China where it arrived at a time of high prices of almost £50 a ton for a commodity the gathering of which by the natives at Eromanga had been paid for with old hoop-iron, axes and assorted ironmongery.[16] Later in the 1840s he began to establish trading posts on the islands to gather sandalwood, beche-de-mer and coconut oil for collection by his island trading vessels. Trading posts were established at New Caledonia (in 1847), the Isle of Pines (1848) and at Aneityum (1853).[17] The commodities collected there he sometimes shipped to China on his own vessels. On the return journey they would bring consignments of tea, rice and sugar from ports in Asia. Some of these cargoes, particularly during the gold rush years, were highly profitable.

The search for cheap labour

Towns had trouble finding men to work in his various enterprises, as did other employers in New South Wales. A Coolie Immigration Society was established in Sydney in September 1842 to lobby the government to remove restrictions on importing labourers from India.[18] The ship Orwell arrived in Sydney 23 March 1846 with 56 male and 13 female “coolies” recruited for Robert Towns in Calcutta, supposedly to work as “domestic servants.”[19] On the voyage out they had to work the pumps of the leaky ship day and night. They were given insufficient food and little warm clothing and all of them became unwell and one died soon after arrival.[20] In Sydney the men were put to work on Towns wharf but they stopped work after a few days. They said their food was inadequate and the terms of their employment had never been made clear to them.[21]

Three hundred Chinese labourers were landed from Towns ship Royal Saxon in 1853 to help meet the labour shortage caused by the Australian Gold Rushes but he found it difficult to place them with other employers.[22] Towns was the leading figure in the trade and had brought in 2,400 Chinese by 1854 as well as 86 Indian workers.[23] He tried to import Chinese and Indian labourers to work on his cotton plantation in Queensland but was frustrated by British government emigration agents in India and Hong Kong.[24] He then looked to bring in indentured labourers from the Pacific Islands.

The South Sea islanders who served as seamen on Towns' sandalwood vessels and pelagic whaling ships performed well and may have prompted him to import large numbers of them into Australia to work on his pastoral properties and cotton plantation in Queensland. The recruiters employed to bring the islanders to Australia sometimes used unscrupulous methods to get them aboard their ships.[25] Some of them were accused of being blackbirders and slavers and his association with them has tarnished Towns reputation.

In a letter to William de Salis dated Sydney, 4 January 1853 Towns describes a shipping issue: "I am afraid our Coolie trade is over, the rascals have been so troublesome, nobody likes to employ them, and our laws are so defective & punishment so trifling for such offences that they laugh at the idea of being put in jail – It is possible she may get a Charter elsewhere with Coolies..."

Whaling from Sydney

Towns was a major figure in whaling in Australia during the mid 19th century.[26] He thought Port Jacksons close proximity to the whaling grounds of the western Pacific made it a "legitimate" enterprise for maritime entrepreneurs based in Sydney.[27] The "lottery aspect" of the industry he felt could be eliminated with a sufficient number of vessels and so he tried to have a fleet of a dozen deep-sea whalers operating at any one time.[28] All told he owned, or part-owned, 23 Sydney whaling vessels at various times. These made 125 voyages from Port Jackson during his thirty or so years involvement in the trade. This in spite of the fact he arrived late on the scene, the industry having peaked in the 1830s.[29]

His strategy was to purchase old and inexpensive vessels and crew them with South Sea islanders who were more tractable and prepared to work on the "lay" or share system of payment. He chose experienced and capable masters to command these vessels and keep them at sea in the face of the manifold difficulties routinely experienced on their long and demanding voyages. It was sometimes hard to get insurance for his aged vessels, eight of which were lost at sea.[30] Crews were also difficult to find at times, especially during the gold rush period in the 1850s, forcing him to send his ships to Hobart or the South Sea islands for men.[31] In spite of the challenges, and the disapproval of his business partners, he persisted through into the 1860s and 1870s when, almost single-handed, he kept the whaling trade alive from Sydney.

He was flexible in the way he used his vessels. He would get his returning whalers to call at island trading stations to pick up casks of coconut oil, trepang of tortoise-shell. At other times he took some ships out of whaling altogether and sent them on trading voyages.

Towns as a civic leader

Towns was a member of the initial New South Wales Legislative Council from 22 May 1856 to 10 May 1861 (a 5-year appointment, terminated by his resignation in support of the council president) and then re-appointed for life on 23 June 1863, terminating at his death on 11 April 1873.[32] Although he did not take a leading part in politics, his advice was much sought in matters affecting business.[33] He was a member and president of the Sydney Chamber of Commerce, a member of the Pilot Board and on the committee of the Sydney Bethel Union. He was also a supporter and promoter of trans-Pacific steam navigation.[34]

He lived from 1864 to 1873 in Cranbrook House on New South Head Road in Rose Bay, Sydney.[35]

Queensland

A world shortage of cotton, due to blockades of Confederate ports during the American Civil War, prompted the Queensland government to encourage the cultivation of cotton in the sub-tropical climate of the colony. Robert Towns was the first to take up this opportunity and brought in indentured Pacific Island labourers to work on his cotton plantation of Townsvale near Brisbane in 1863.[36] Towns actively promoted this remedy to the labour shortage in rural Queensland in a pamphlet published in 1864.[37]

Between 1864 and 1904, an estimated 63,000 women and men came to Australia to work in the shipping and sugar industries. Many were poorly paid and endured harsh conditions. It has been alleged that those acting on behalf of Towns and others engaged in blackbirding, the practise of coercing and kidnapping labourers when they could not obtain workers to come voluntarily.[38][39]

Many attempts had been made to grow cotton in Australia before this time, but Towns was the first to do so on a large scale. Realizing that a port was needed on the Queensland coast north of Bowen, Towns arranged for explorations to be made from his stations, a suitable site was found at Cleveland Bay, and on to October 1865 it was gazetted as a port of entry and named Townsville.

Local legend (as yet unsubstantiated) suggests that Towns was involved in a coffee planting venture. The story goes that Towns was privy to a plan by the government to grant title to land under cultivation. He procured a boat load of coffee beans, arranged for them to be planted on a substantial tract of land in the Townsville area and applied for the title to the land. The coffee crop failed because the beans had been roasted before Towns acquired them. However, this detail did not prevent Towns from succeeding in his efforts to acquire the land.

Later life

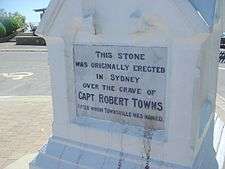

In 1870, Robert Towns was attacked by paralysis and his health was precarious thereafter. He suffered a further stroke on 7 April 1873 and died at his home, Cranbrook, on 11 April 1873.[40][33] He was buried on 15 April 1873 in the Balmain Cemetery.[41][42] The Balmain Cemetery closed in 1912 and, in 1941, it was decided to convert it into parkland (the Pioneer's Memorial Park) and advertisements were placed for families to make arrangements for re-interment of bodies or removal of memorials. As a result, the memorial stone from Robert Town's grave was relocated to stand atop a monument at Castle Hill, Townsville.[43]

After a number of subsequent owners, his home Cranbrook House would become Cranbrook School.

On Sunday 1 November 1964, the Townsville Centenary Monument was unveiled on The Strand commemorating 100 years of European settlement in Townsville, with particular mention made of four men: Robert Towns, Andrew Ball, Mark Watt Reid and John Melton Black.[44]

References

- ↑ Frank Broeze, Mr Brooks and the Australian trade; imperial business in the nineteenth century, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1993, p.207 & 268.

- ↑ D. Shineberg, “Towns, Robert, (1794-1873,” Australian Dictionary of National Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National Biography, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Ian Nicholson, Shipping arrivals and departures, Sydney, 1826-1840, Roebuck, Canberra, 1891, p.18.

- ↑ Nicholson, p.87.

- ↑ Frank Broeze, "Australia, Asia and the Pacific: the maritime world of Robert Towns 1843-1873," Australian Historical Studies, 24 (95) October 1990, p.223.

- ↑ Broeze (1990) p.223.

- ↑ Shineberg, D. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ "Marriage Records Search". New South Wales Government. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ "Family Notices". The Australian. Sydney. 3 January 1834. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Ronald Parsons, Ships of Australia and New Zealand before 1850, A-J, McGill, South Australia, 1983, p.58.

- ↑ Nairn, Bede; Rutledge, Martha. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ Broeze (1990), p.224.

- ↑ Broeze (1990) p.224-5.

- ↑ Broeze (1990) p.224.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald, 30 June 1845, p.2)

- ↑ Dorothy Shineberg, They came for sandalwood: a study of the sandalwood trade in the South-West Pacific 1830-1865, Melbourne University Press, 1967, p.110.

- ↑ Shineberg (1967) pp.116-7.

- ↑ Australasian Chronicle, 24 September 1842, p.2.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald, 26 March 1846, p.2.

- ↑ Morning Chronicle, 4 April 1846, p.2.

- ↑ Morning Chronicle, 8 April 1846, p.2&3

- ↑ Broeze (1990) p.231.

- ↑ A. T. Yarwood, Attitudes to non-European immigration, Cassel, Sydney, 1988, p.15

- ↑ Broeze (1990) p.232

- ↑ George Palmer, Kidnapping in the South Seas; being a narrative of a three months cruise of H. M. Ship Rosario, Edinburgh, 1871, pp.107-109; Doug Hunt, "Hunting the blackbirder: Ross Lewin and the Royal Navy," Journal of Pacific History, 42 (1) June 2007, pp.37-53.

- ↑ William Dakin, Whalemen adventurers; the story of whaling in Australian waters and other southern seas related thereto, from the days of sails to modern tines, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1938, p.115.

- ↑ Broeze (1990) p.237.

- ↑ Broeze (1990) p.234

- ↑ Sydney's whaling fleet, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Dakin, p.116

- ↑ Dakin, p.117-8

- ↑ "Mr Robert Towns (1794–1873)". Former Members. New South Wales Parliament. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- 1 2 "The Hon. Robert Towns". Australian Town and Country Journal. Sydney. 19 April 1873. p. 9 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Broeze (1993) p.248.

- ↑ Shineberg, D. "Towns, Robert (1794–1873)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ James Stuart Olson & Robert Shadie (Eds.) Historical dictionary of the British Empire, Greenwood, 1996, p.142.

- ↑ Captain Robert Towns, South Sea Island Immigration for Cotton Cultivation: a letter to the Honourable Colonial Secretary of Queensland, Sydney, Reading & Wellbank, 1864.

- ↑ "'Blackbirding' shame yet to be acknowledged in Australia". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 3 June 2013. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Haxton, Nance (24 August 2017). "South Sea Islanders say statue of Townsville founder 'whitewashes' slave history". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 April 1873. p. 1 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 April 1873. p. 12 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Balmain Cemetery Registry Index: 1868-1912" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ "Balmain Cemetery". Leichhardt City Council. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ "Townsville Centenary Monument | Monument Australia". monumentaustralia.org.au. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

External links

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Towns, Robert". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.