Razing of Friesoythe

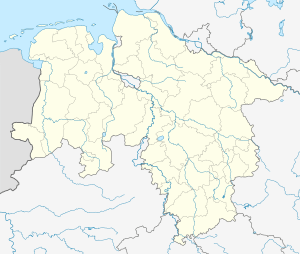

| Friesoythe | |

|---|---|

Friesoythe Friesoythe within Lower Saxony, Germany | |

| Coordinates: 53°01′14″N 07°51′31″E / 53.02056°N 7.85861°ECoordinates: 53°01′14″N 07°51′31″E / 53.02056°N 7.85861°E |

Photograph: A Stirton, Library and Archives Canada

The Razing of Friesoythe took place on 14 April 1945 during the Western Allies' invasion of Germany towards the end of World War II. In early April, the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division, advancing into north-west Germany, attacked the German town of Friesoythe. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, captured the town. During the fighting the battalion's commander was killed by a German soldier and it was rumoured that he had been killed by a civilian.

Under this mistaken belief the division's commander, Major General Christopher Vokes, ordered that the town be razed in retaliation and it was substantially destroyed. The rubble was used to fill craters in local roads to make them passable for the division's tanks and heavy vehicles. A few days earlier the division had destroyed the centre of Sögel in another reprisal and used the rubble to make the roads passable.

Little official notice was taken of the incident and the official history glosses over it. It is covered in the regimental histories of the units involved and several accounts of the campaign. Forty years afterwards, Vokes wrote in his autobiography that he had "no great remorse over the elimination of Friesoythe". There has been no investigation by Canadian authorities of the event.

Context

In early April 1945 the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division, part of II Canadian Corps, moved out of the eastern Netherlands as the Western Allies launched their invasion of Germany in the wake of the crossing of the Rhine in Operation Plunder. The Canadian official history described the circumstances as buoyant as it was recognised that the end of World War II in Europe was close.[1] On 4 April, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, part of the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division, made an assault crossing of the Ems river and captured the town of Meppen, suffering only one casualty. German prisoners included several 17-year-old youths with less than eight weeks military experience.[2]

Battle for Sögel

The division advanced a further 25 kilometres (16 mi) to Sögel, which the Lake Superior Regiment (Motor) captured on 9 April. The following day it repulsed several German counter-attacks before the town was declared cleared.[3][4] Some German civilians joined the fighting and were believed to have killed several Canadian soldiers. Major General Christopher Vokes, the divisional commander, believing the civilians needed to be taught a lesson, ordered the destruction of the centre of the town.[5] This was accomplished with several truck-loads of dynamite. Soldiers of the division started referring to Vokes as "The Sod of Sögel".[6]

Investigation established that German civilians had taken part in this fighting and had been responsible for the loss of Canadian lives. Accordingly, as a reprisal and a warning, a number of houses in the centre of Sögel were ordered destroyed by the engineers to provide rubble.

— The Victory Campaign, C. P. Stacey (1960)[4]

Battle for Friesoythe

The Canadian advance continued across the Westphalian Lowland, reaching a strategic crossroads on the outskirts of Friesoythe on 13 April. As it was early spring the ground was sodden and heavy vehicles could not operate off the main roads.[4] This made Friesoythe, 20 miles (32 km) west of Oldenburg, on the river Soeste, a potential bottleneck. If the Germans were to hold it, the bulk of the Canadians would not be able to continue their advance.[7] Most of the population of 4,000 had evacuated to the countryside on 11–12 April.[Note 1] Several hundred paratroopers from Battalion Raabe of the 7th Parachute Division and a number of anti-tank guns defended the town.[7][8] The paratroopers repelled the first attack by the Lake Superior Regiment, which suffered a number of killed and wounded; German casualties are unknown.[9]

Vokes ordered the resumption of the attack by the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick E. Wigle). The Argylls conducted a flanking night march and launched a dawn attack on 14 April. The attack met only scattered resistance from a disorganized garrison and the Argylls secured the town by 10:30 a.m. During the attack, a small number of German soldiers caught Wigle's tactical headquarters by surprise at around 8:30 a.m. A firefight broke out, resulting in the death of Wigle and several other soldiers. A rumour circulated that a local civilian had shot Wigle.[10][11][12]

Destruction of Friesoythe

Vokes was furious when he heard of Wigle's death and wrote in his autobiography "A first-rate officer of mine, for whom I had a special regard and affection, and in whom I had a particular professional interest because of his talent for command, was killed. Not merely killed, it was reported to me, but sniped in the back". Vokes wrote "I summoned my GSO1... 'Mac,' I roared at him, 'I'm going to raze that goddam town. Tell 'em we're going to level the fucking place. Get the people the hell out of their houses first.'"[6][13]

The Argylls had spontaneously begun to burn Friesoythe in reprisal for the death of their colonel.[14] After Vokes issued his order, the town was systematically set on fire with flamethrowers mounted on Wasp Carriers. Other soldiers fanned out down side streets, throwing phosphorus grenades or improvised Molotov cocktails made from petrol containers into buildings. The attack continued for over eight hours and Friesoy was almost totally destroyed.[10] As the commanding officer of The Algonquin Regiment later wrote, "the raging Highlanders cleared the remainder of that town as no town has been cleared for centuries, we venture to say".[15] The war diary of the 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade records, "when darkness fell Friesoythe was a reasonable facsimile of Dante's Inferno".[16]

The Canadian official history volume states that Friesoythe "was set on fire in a mistaken reprisal".[17] The rubble was used to reinforce the local roads for the division's tanks, which had been unable to move up due to the roads near the town being badly cratered.[18][19]

Several attempts were made to find passable roads to carry the vehicles, but the main highway between Cloppenburg and Friesoythe was seriously cratered near the latter town, and the small roads would not stand up to the traffic.[18]

Civilian casualties and damage

During the fighting around Friesoythe and aftermath, ten civilians from the town and another ten from the surrounding villages were killed.[20] There were reports of civilians lying dead in the streets.[10] According to one German assessment, 85–90 per cent of the town was destroyed during the reprisal.[21] The Brockhaus Enzyklopaedie, estimated the destruction to be as high as 90 per cent. The town's website records that of 381 houses in the town proper, 231 were destroyed and another 30 badly damaged.[20] A few days later, a Canadian nurse wrote home that the convent on the edge of town was the only building left standing.[22] In the suburb of Altenoythe, 120 houses and 110 other buildings were destroyed.[20] In 2010, Mark Zuehlk suggested that, "Not all of Friesoythe was burnt, but its centre was destroyed".[16]

Aftermath

Major General Christopher Vokes in his autobiography[23]

The Argyll's war diary made no mention of their afternoon's activity, noting in passing that "many fires were raging." There is no record of the deliberate destruction at division, corps or army level.[16] The war diary of the division's 8th Anti-Aircraft Regiment records "the Argylls were attacked in that town yesterday by German forces assisted by civilians and today the whole town is being systematically razed. A stern atonement...."[16] On 16 April the Lincoln and Welland Regiment attacked Garrel, 10 miles (16 km) south-west of Friedsoythe. After a German act of perfidy the mayor surrendered the town but the first tank to enter was destroyed by a panzerfaust the battalion commander, Wigle's brother-in-law, ordered that "every building which did not show a white flag be fired".[24] In the event the village was spared.[25]

The Canadian army official historian, Colonel Charles Stacey visited Friesoythe on 15 April and in the Canadian Army official history, "There is no record of how this [destruction] came about" (1960).[16][26] Stacey commented in 1982 in his memoirs that the only time he saw what could be considered a war crime committed by Canadian soldiers was when

... at Friesoythe, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada of this division lost their popular commanding officer... as a result a great part of the town of Friesoythe was set on fire in a mistaken reprisal. This unfortunate episode only came to my notice and thus got into the pages of history because I was in Friesoythe at the time and saw people being turned out of their houses and the houses burned. How painfully easy it is for the business of "reprisals" to get out of hand!

After the war the Vokes said, referring to a discussion with the Canadian High Commissioner in London regarding the sentencing of convicted German war criminal Kurt Meyer, "I told them of Sögel and Friesoythe and of the prisoners and civilians that my troops had killed in Italy and Northwest Europe".[6] Vokes commented in his autobiography, written forty years after the event, that he had "[a] feeling of no great remorse over the elimination of Friesoythe. Be that as it may".[6][28] The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders was awarded the battle honour "Friesoythe", as were The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor) and The Lincoln and Welland Regiment.[29] There was no investigation by Canadian authorities of the damage or the civilian casualties. In 2010, Mark Zuehlke wrote "No evidence of a deliberate cover up exists".[16]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Friesoythe Amtsgericht, or District Court, was closed on 11 April. If the District Court ceased to function on 11 April 1945, the evacuation of the bulk of the civilian population probably took place between 11 April and 12 April. It was clearly a German and not a Canadian initiative.(Cloppenburg 2003, pp. 165, 189)(Brockhaus 1996, p. 730)

- ↑ For example, the 1907 Convention Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV), Article 23, prohibits acts that "destroy or seize the enemy's property, unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war."("Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land". ihl-databases.icrc.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018. )

Footnotes

- ↑ Stacey 1960, p. 527.

- ↑ Stacey 1960, p. 557.

- ↑ Williams 1988, p. 276.

- 1 2 3 Stacey 1960, p. 558.

- ↑ Morton, Desmond. "Christopher Vokes". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Foster 2000, p. 437.

- 1 2 Zuehlke 2010, p. 305.

- ↑ War Diary, General Staff, 4th Canadian Armoured Division, 1 April 1945 – 30 April 1945. Appendix 38; dated April 14th, 1945. Library and Archives Canada, RG 24, vol. no. 13794. Intelligence report signed: E. Sirluck, Capt.

- ↑ Marsh, James H. "One More River to Cross: The Canadians in Holland". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Zuehlke 2010, p. 308.

- ↑ War Diary, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, April 14, 1945, pp. 10–11. Ottawa, ON, Canada. National Archives of Canada, RG 24, v. 15,005.

- ↑ Fraser 1996, p. 431.

- ↑ Vokes 1985, pp. 194–5.

- ↑ Fraser 1996, pp. 435–7.

- ↑ Cassidy 1948, p. 307.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zuehlke 2010, p. 309.

- ↑ Stacey 1960, p. 722.

- 1 2 Rogers 1989, p. 259.

- ↑ "Legion Magazine" (PDF). May–June 2010. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 Friesoythe. "Chronik – 1930 bis 1948 | Stadt Friesoythe" (in German). Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ↑ Cloppenburg 2003, p. 189.

- ↑ Hibbert 1985, p. 84.

- ↑ Vokes 1985, p. x.

- ↑ Lincoln and Welland Regiment War Diary, April 1945, RG24, Library and Archives Canada, 8

- ↑ Zuehlke 2010, p. 312.

- ↑ Stacey 1960, pp. 558, 722.

- ↑ Stacey 1982, pp. 163–64.

- ↑ Morton 2016.

- ↑ "The Insignia and Linages of the Canadian Forces. Volume 3, Part Two. "Infantry Regiments"" (PDF). A Canadian Forces Heritage Publication. 13 August 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Cassidy, G. L. (1948). Warpath; the Story of the Algonquin Regiment, 1939–1945. Toronto: Ryerson Press. OCLC 937425850.

- Cloppenburg, Ferdinand (2003). Die Stadt Friesoythe im zwanzigsten Jahrhundert [The town of Friesoythe in the twentieth century)] (in German). Friesoythe: Schepers. ISBN 978-3000127595.

- Foster, Tony (2000). Meeting of Generals. San Jose; New York: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-13750-3.

- Fraser, Robert L. (1996). Black Yesterdays; the Argylls' War. Hamilton: Argyll Regimental Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9681380-0-7.

- Hibbert, Joyce (1985). Fragments of War: Stories from Survivors of World War II. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-0-919670-95-2.

- Morton, Desmond (2016) [2008]. "Christopher Vokes". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Rogers, R. L. (1989). History of The Lincoln and Welland Regiment. Ottawa: Private printing. OCLC 13090416.

- Sirluck, E. (14 April 1945). Intelligence Report, War Diary, General Staff, 4th Canadian Armoured Division, 1 April 1945 – 30 April 1945. Appendix 38.

- Stacey, Charles Perry (1960). The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-west Europe 1944–45 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. III. Ottawa: Queen's Printer. OCLC 317352926.

- Stacey, Charles Perry (1982). A Date With History. Ottowa: Deneau. ISBN 978-0-88879-086-6.

- Vokes, Chris (1985). Vokes: My Story. Ottawa: Gallery Books. ISBN 978-0-9692109-0-0.

- Williams, Jeffery (1988). The Long Left Flank: the Hard Fought Way to the Reich, 1944–1945. Toronto: Stoddart. ISBN 978-0-7737-2194-4. OCLC 25747884.

- Zuehlke, Mark (2010). On To Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands. Vancouver: Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-55365-430-8.

- Die Enzyklopädie, 20. Aufl. V. 7. Leipzig: Brockhaus. 1996.

- Lincoln and Welland Regiment War Diary, April 1945. Library and Archives Canada. RG24.