rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine

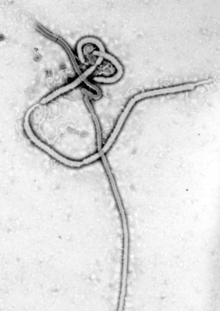

An electron micrograph of the Ebola virus | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Ebola virus |

| Type | Recombinant vector |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus (rVSV-ZEBOV) is an experimental vaccine for protection against Ebola virus disease.[1][2] As of April 2017, ring vaccination with rVSV-ZEBOV appeared to be somewhat effective, but the extent of efficacy was uncertain.[3] When used in ring-vaccination, rVSV-EBOV has shown a high level of protection.[4] Around half the people given the vaccine have mild to moderate adverse effects that include headache, fatigue, and muscle pain.[4]

rVSV-ZEBOV is a recombinant, replication-competent vaccine.[5] It consists of a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), which has been genetically engineered to express a glycoprotein from the Zaire ebolavirus so as to provoke a neutralizing immune response to the Ebola virus.

It was created by scientists at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, which is part of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).[6] PHAC licensed it to a small company, NewLink Genetics, which started developing the vaccine; NewLink in turn licensed it to Merck in 2014.[7] It was used in the DR Congo in a 2018 outbreak in Équateur province.[8]

Medical use

As of April 2017, ring vaccination with rVSV-EBOV appeared to be somewhat effective, but the extent of efficacy was uncertain, due to the trial design and elimination of the delayed treatment arm part way through the trial.[3]

Nearly 800 people were ring vaccinated on an emergency basis with VSV-EBOV when another Ebola outbreak occurred in Guinea in March 2016.[9] In 2017, in the face of a new outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Ministry of Health approved the vaccine's emergency use,[10][11], but it was not immediately deployed.[12]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects have occurred in around half the people given the vaccine, were generally mild to moderate, and included headache, fatigue, and muscle pain.[4][13][14]

Chemistry

rVSV-ZEBOV is a live, attenuated recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus in which the gene for the native envelope glycoprotein is replaced with that from the Ebola virus, Kikwit 1995 Zaire strain.[15][13][16] Manufacturing of the vaccine for the Phase I trial was done by IDT Biologika.[17][18] Manufacturing of vaccine for the Phase III trial was done by Merck, using cells from African green monkeys, which Merck already used to make its RotaTeq vaccine against rotavirus.[19][20]

History

Scientists working for the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) created the vaccine, and PHAC applied for a patent in 2003.[6][21] From 2005 to 2009, three animal trials on the virus were published, all of them funded by the Canadian and U.S. governments.[18] In 2005, a single intramuscular injection of the EBOV or MARV vaccine was found to induce completely protective immune responses in nonhuman primates (crab-eating macaques) against corresponding infections with the otherwise typically lethal EBOV or MARV.[22][23]

In 2010, PHAC licensed the intellectual property on the vaccine to a small U.S. company called Bioprotection Systems, which was a subsidiary of NewLink Genetics; Newlink had funding from the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency to develop vaccines.[6][24][25]

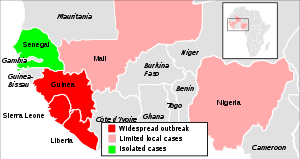

In December 2013, the largest-ever Ebola epidemic started in West Africa, specifically, in Guinea.[26] In September or October 2014, Newlink formed a steering committee among the interested parties, including PHAC, the NIH, and the WHO, to plan the clinical development of the vaccine.[27][28]

In October 2014, NewLink Genetics began a Phase I clinical trial of rVSV-ZEBOV on healthy human subjects to evaluate the immune response, identify any side effects and determine the appropriate dosage.[24][29][30] Phase I trials took place in Gabon, Kenya, Germany, Switzerland, the US, and Canada.[31][32] In November 2014 NewLink exclusively licensed rights to the vaccine to Merck.[7]

The Phase I study started with a high dose which caused arthritis and skin reactions in some people, and the vaccine was found replicating in the synovial fluid of the joints of the affected people; the clinical trial was halted because of that, then recommenced with a lower dose.[33]

In March 2015, a Phase II clinical trial and a Phase III started in Guinea at the same time; the Phase II trial focused on frontline health workers, while the Phase III trial was a ring vaccination in which close contacts of people who had contracted Ebola virus were vaccinated with VSV-EBOV.[34] Preliminary results were reported in July.[35] In the same report, the WHO communicated that the control arm of the trial was dropped and the trial would expand.[36]

In January 2016, the GAVI Alliance signed an agreement with Merck under which Merck agreed to provide VSV-EBOV vaccine for future outbreaks of Ebola and GAVI paid Merck US$5 million; Merck will use the funds to complete clinical trials and obtain regulatory approval. As of that date Merck had submitted an application to the World Health Organization through their Emergency Use Assessment and Listing (EUAL) program to allow for use of the vaccine in the case of another epidemic.[37] It was used on an emergency basis in Guinea in March 2016.[9]

Results of the Phase III Guinea trial were published in December 2016. It was widely reported in the media that vaccine was safe and appeared to be nearly 100% effective,[3][38] but the vaccine remained unavailable for commercial use as of December 2016.[39]

In April 2017, scientists from the U.S. National Academy of Medicine published a review of the response to the Ebola outbreak that included a discussion of how clinical trial candidates were selected, how trials were designed and conducted, and reviewed the data resulting from the trials. The committee found that data from the Phase III Guinea trial were difficult to interpret for several reasons. The trial had no placebo arm; it was omitted for ethical reasons and everyone involved, including the committee, agreed with the decision. This left only a delayed treatment group to serve as a control, but this group was eliminated after an interim analysis showed high levels of protection, which left the trial even more underpowered. The committee found that under an intention-to-treat analysis, the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine might have had no efficacy, agreed with the authors of the December 2016 report that it probably had some efficacy, but found statements that it had substantial or 100% efficacy to be unsupportable.[3]

2018 Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus outbreak

During an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018, the ZEBOV vaccine was used,[40] and what was once contact tracing which numbered 1,706 individuals (ring vaccination which totaled 3,330) was reduced to zero on 28 June 2018.[41] The outbreak will complete the required 42-day cycle on 24 July.[42][43][44][45]

See also

References

- ↑ Trad, MA; Naughton, W; Yeung, A; Mazlin, L; O'sullivan, M; Gilroy, N; Fisher, DA; Stuart, RL (January 2017). "Ebola virus disease: An update on current prevention and management strategies". Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 86: 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2016.11.005. PMID 27893999.

- ↑ Pavot, Vincent (1 December 2016). "Ebola virus vaccines: Where do we stand?". Clinical Immunology. 173: 44–49. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2016.10.016.

- 1 2 3 4 Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014-2015 Ebola Outbreak; Board on Global Health; Board on Health Sciences Policy (April 2017). Integrating Clinical Research into Epidemic Response: The Ebola Experience. The National Academies Press. pp. 119–131.

- 1 2 3 Medaglini, D; Siegrist, CA (April 2017). "Immunomonitoring of human responses to the rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine". Current Opinion in Virology. 23: 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2017.03.008. PMID 28460340.

- ↑ Marzi, Andrea; et al. "Vesicular Stomatitis Virus–Based Ebola Vaccines With Improved Cross-Protective Efficacy". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (suppl 3): S1066–S1074. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir348. PMC 3203393. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Denise Grady for the New York Times. October 23, 2014 Ebola Vaccine, Ready for Test, Sat on the Shelf

- 1 2 "Merck & Co. Licenses NewLink's Ebola Vaccine Candidate". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. November 24, 2014.

- ↑ McKenzie, David (26 May 2018). "Fear and failure: How Ebola sparked a global health revolution". CNN. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- 1 2 "WHO coordinating vaccination of contacts to contain Ebola flare-up in Guinea". World Health Organization. March 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Congo approves use of Ebola vaccination to fight outbreak". Reuters. 29 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ↑ Maxmen, Amy. "Ebola vaccine approved for use in ongoing outbreak". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22024.

- ↑ "Ebola virus disease: Democratic Republic of the Congo: External Situation Report 22" (PDF). WHO. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- 1 2 Martínez-Romero C, García-Sastre A (2015). "Against the clock towards new Ebola virus therapies". Virus Res. 209: 4–10. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2015.05.025. PMID 26057711.

- ↑ Miriam Shuchman for the Lancet World Report. May 12, 2015 Ebola vaccine trial in west Africa faces criticism

- ↑ Choi WY (Jan 2015). "Progress of vaccine and drug development for Ebola preparedness". Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 4 (1): 11–16. doi:10.7774/cevr.2015.4.1.11. PMC 4313103. PMID 25648233.

- ↑ Regules JA; et al. (Apr 2015). "A Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Ebola Vaccine – Preliminary Report". N Engl J Med. 376: 150414100104004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414216. PMID 25830322.

- ↑ Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève FAQs about the context of this clinical trial: Question 22

- 1 2 The strange tale of Canada’s ebola vaccine: Walkom. Commercial rights to a vaccine worth $50 million were sold to a U.S. middleman for $205,000. By Thomas Walkom, The Star, November 25, 2014

- ↑ Carly Helfand for FierceVaccine. November 21, 2014 NewLink, Merck sign Ebola vaccine licensing pact

- ↑ Zachary Brennan for BioPharma Reporter. November 25, 2014. Merck to manufacture NewLink Ebola vaccine in-house

- ↑ Published PCT Application WO2004011488: Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vaccines for viral hemorrhagic fevers, claiming priority to US provisional patent application serial number 60/398,552 filed on July 26, 2003.

- ↑ Sylvain Baize (2005). "A single shot against Ebola and Marburg virus". Nature Medicine. 11 (7): 720–21. doi:10.1038/nm0705-720.

- ↑ Steven M. Jones with thirteen others (2005). "Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses". Nature Medicine. 11 (7): 786–90. doi:10.1038/nm1258. PMID 15937495.

- 1 2 "Ebola outbreak: 1st human trials of Canadian vaccine start in U.S." CBC News. October 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Sole Redacted License Agreement for Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Vaccines for Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers". Public Health Agency of Canada.

- ↑ "Origins of the 2014 Ebola epidemic". World Health Organization. January 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ↑ Patricia Van Arnum for DCAT. October 21, 2014 Pharmaceutical companies join the effort to develop and produce vaccines and treatments for the Ebola virus

- ↑ Helen Branswell (October 8, 2014). "Canadian Ebola vaccine safety trials move ahead, NewLink Genetics says". CBC News. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Canadian Ebola vaccine license holder moving ahead with safety trials". Canadian Press. October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ↑ "A Phase 1 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled, Dose-Escalation Study to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of Prime-Boost VSV Ebola Vaccine in Healthy Adults". US NIAID. October 9, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ↑ Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève FAQs about the context of this clinical trial: Question 10

- ↑ "Table of vaccine clinical trials". World Health Organization. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ↑ Medaglini, D; Harandi, AM; Ottenhoff, TH; Siegrist, CA; VSV-Ebovac, Consortium. (9 December 2015). "Ebola vaccine R&D: Filling the knowledge gaps". Science Translational Medicine. 7 (317): 317ps24. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3106. PMID 26659569.

- ↑ WHO and MSF, 17 July 17, 2015. Q&A on trial of Ebola Virus Disease vaccine in Guinea

- ↑ James Gallagher (July 31, 2015). "Ebola vaccine is 'potential game-changer'". BBC News Health. UK: BBC. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ↑ Henao-Restrepo, Ana Maria; et al. (July 31, 2015). "Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine expressing Ebola surface glycoprotein: interim results from the Guinea ring vaccination cluster-randomised trial" (PDF). The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140673615611175. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ↑ Hirshler, Ben; Kelland, Kate (January 20, 2016). "Vaccines alliance signs $5 million advance deal for Merck's Ebola shot". Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ↑ Geisbert, TW (22 December 2016). "First Ebola virus vaccine to protect human beings?". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32618-6. PMID 28017402.

- ↑ Lisa Schnirring (27 December 2016). "Ebola vaccine highly effective in final trial results". CIDRAP. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ↑ CNN, Joshua Berlinger,. "Congo to begin vaccinating against Ebola". CNN. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ↑ "EBOLA RDC - Communication spéciale du Ministre de la Santé concernant l'évolution de la neuvième épidémie d'Ebola en RDC". us13.campaign-archive.com. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ↑ "WHO AFRO Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, Week 26: 23 - 29 June 2018 (Data as reported by 17:00; 29 June 2018)". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ↑ Schlein, Lisa. "Congo Ebola Outbreak Expected to End Next Week". VOA. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ↑ "Media Advisory: Expected end of Ebola outbreak". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Ebola outbreak in DRC ends: WHO calls for international efforts to stop other deadly outbreaks in the country". World Health Organization. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

Further reading

| Wikinews has related news: Study confirms efficacy of NewLink Genetics ebola vaccine |

- "Scientists hail '100% effective' Ebola vaccine – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. National Institute of Health. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- Marzi, Andrea; Robertson, Shelly J.; Haddock, Elaine; Feldmann, Friederike; Hanley, Patrick W.; Scott, Dana P.; Strong, James E.; Kobinger, Gary; Best, Sonja M.; Feldmann, Heinz (August 14, 2015). "VSV-EBOV rapidly protects macaques against infection with the 2014/15 Ebola virus outbreak strain". Science. 349 (6249): 739–742. doi:10.1126/science.aab3920. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26249231. Retrieved July 21, 2016.