Fitness to dive

Fitness to dive, (also medical fitness to dive), is the medical and physical suitability of a diver to function safely in the underwater environment using underwater diving equipment and procedures. Depending on the circumstances it may be established by a signed statement by the diver that he or she does not suffer from any of the listed disqualifying conditions and is able to manage the ordinary physical requirements of diving, to a detailed medical examination by a physician registered as a medical examiner of divers following a procedural checklist, and a legal document of fitness to dive issued by the medical examiner.

The most important medical is the one before starting diving, as the diver can be screened to prevent exposure when a dangerous condition exists. The other important medicals are after some significant illness, where medical intervention is needed there and has to be done by a doctor who is competent in diving medicine, and can not be done by prescriptive rules.[1]

Psychological factors can affect fitness to dive, particularly where they affect response to emergencies, or risk taking behaviour. The use of medical and recreational drugs, can also influence fitness to dive, both for physiological and behavioural reasons. In some cases prescription drug use may have a net positive effect, when effectively treating an underlying condition, but frequently the side effects of effective medication may have undesirable influences on the fitness of diver, and most cases of recreational drug use result in an impaired fitness to dive, and a significantly increased risk of sub-optimal response to emergencies.

General requirements

The medical, mental and physical fitness of professional divers is important for safety at work for the diver and the other members of the diving team.[2]

As a general principle, fitness to dive is dependent on the absence of conditions which would constitute an unacceptable risk for the diver, and for professional divers, to any member of the diving team. General physical fitness requirements are also often specified by a certifying agency, and are usually related to ability to swim and perform the activities that are associated with the relevant type of diving.

The general hazards of diving are much the same for recreational divers and professional divers, but the risks vary with the diving procedures used. These risks are reduced by appropriate skills and equipment.

Medical fitness to dive generally implies that the diver has no known medical conditions that limit the ability to do the job, jeopardise the safety of the diver or the team, that might get worse as an effect of diving, or predispose the diver to diving or occupational illness.[2]

There are three types of diver medical assessment: initial assessments, routine re-assessments and special re-assessments after injury or decompression illness.[2]

Fitness of recreational divers

Standards for fitness to dive are specified by the diver certification agency which will issue certification to the diver after training. Some agencies consider assessment of fitness to dive as largely the responsibility of the individual diver, others require a registered medical practitioner to make an examination based on specified criteria. These criteria are generally common to certification agencies, and are based on the criteria for professional divers, though the standards may be relaxed.

The purpose of establishing fitness to dive is to reduce risk of a range of diving related medical conditions associated with known or suspected pre-existing conditions, and is not generally an indication of the person's psychological suitability for diving and has no reference to their diving skills.

A certification of fitness to dive is generally for a specified period, (usually a year or less), and may specify limitations or restrictions.

In most cases, a statement or certificate of fitness to dive for recreational divers is only required during training courses. Ordinary recreational diving is at the diver's own risk.

In rare cases, state or national legislation may require recreational divers to be examined by registered medical examiners of divers.[3] In France, Norway, Portugal and Israel. recreational divers are required by regulation to be examined for medical fitness to dive.[4]

Standard forms for recreational diving

Recreational diver certification agencies may provide a standard document[5] which the diver is required to complete, specifying whether any of a range of conditions apply to the diver. If no disqualifying conditions are admitted, the diver is considered to be fit to dive. Occasionally divers have provided deliberately falsified medical forms, stating that they do not have conditions which would disqualify them from diving, sometimes with fatal consequences.[6]

The RSTC medical statement is used by all RSTC member affiliates: RSTC Canada, RSTC, RSTC-Europe and IAC (former Barakuda), FIAS, ANIS, SSI Europe, PADI Norway, PADI Sweden, PADI Asia Pacific, PADI Japan, PADI Canada, PADI Americas, PADI Worldwide, IDD Europe, YMCA, IDEA, PDIC, SSI International, BSAC Japan and NASDS Japan.[7]

Other certification agencies may rely on the competence of a general practitioner to assess fitness to dive, either with or without an agency specified checklist.

In some cases the certification agency may require a medical examination by a registered medical examiner of divers.

Fitness of professional divers

The requirements for medical examination and certification of fitness of professional divers is typically regulated by national or state legislation for occupational health and safety[8][2]

Fitness testing procedures

Lung function tests

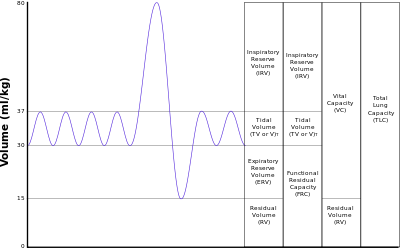

A frequently used test for lung function for divers is spirometry, which measures the amount (volume) and/or speed (flow) of air that can be inhaled and exhaled. Spirometry is an important tool used for generating pneumotachographs, which are helpful in assessing conditions such as asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, cystic fibrosis, and COPD, all of which are contraindications for diving. Sometimes only peak expiratory flow (PEF) is measured, which uses a much simpler apparatus, but is still useful to give an indication of lung overpressure risk.

Cardiac stress test

The cardiac stress test is done with heart stimulation, either by exercise on a treadmill, or pedalling a stationary exercise bicycle ergometer, with the patient connected to an electrocardiogram (or ECG).

The Harvard Step Test is a type of cardiac stress test for detecting and/or diagnosing cardiovascular disease. It also is a good measurement of fitness, and the ability to recover after a strenuous exercise, and is sometimes used as an alternative for the cardiac stress test.

Medical examiner of divers

Disqualifying conditions

The general principles for disqualification are that diving causes a deterioration in the medical condition and the medical condition presents an excessive risk for a diving injury to both the individual and the diving partner.[5]

There are some conditions that are considered absolute contraindications for diving. Details vary between recreational and professional diving and in different parts of the world. Those listed below are widely recognised.

Permanently disqualifying conditions

- If epilepsy is required to be controlled by medication, diving is contraindicated. (This includes childhood seizure disorders requiring medication). A possible acceptable risk would be a history of febrile seizures in infancy, apneic spells or seizures attendant to acute illness such as encephalitis and meningitis, all without recurrence without medication.[9]

- Stroke and transient ischemic attacks.[9]

- Intercranial aneurysm, arterial-venous malformation or tumor.[9]

- Exertional angina, postmyocardial infarction with left ventricular dysfunction, congestive heart failure, or dependence on medication to control dysrhythmias.[9]

- Postcoronary bypass surgery with violation of pleural spaces.[9]

- A history of spontaneous pneumothorax.[9]

Temporarily disqualifying conditions

Any illness requiring drug treatment may constitute a temporary disqualification if either the illness or the drug may compromise diving safety. Sedatives, tranquillisers, antidepressants, antihistamines, anti-diabetic drugs, steroids, anti-hypertensives, anti-epilepsy drugs, alcohol and hallucinatory drugs such as marijuana and LSD may increase risk to the diver. Some drugs which affect brain function have unpredictable effects on a diver exposed to high pressure in deep diving.[10]

Conditions which may disqualify or require restrictions depending on severity and management

Some medical conditions may temporarily or permanently disqualify a person from diving depending on severity and the specific requirements of the registration body. These conditions may also require the diver to restrict the scope of activities or take specific additional precautions. They are also referred to as relative contraindications, and may be acute or chronic.

Asthma

In the past, asthma was generally considered a contraindication for diving due to theoretical concern about an increased risk for pulmonary barotrauma and decompression sickness. The conservative approach was to arbitrarily disqualify asthmatics from diving. This has not stopped asthmatics from diving, and experience in the field and data in the current literature do not support this dogmatic approach. Asthma has a similar prevalence in divers as in the general population.[11]

The theoretical concern for asthmatic divers is that pulmonary obstruction, air trapping and hyperinflation may increase risk for pulmonary barotrauma, and the diver may be exposed to environmental factors that increase the risk of bronchospasm and the development of an acute asthmatic attack which could lead to panic and drowning. As of 2016, there is no epidemiological evidence for an increased relative risk of pulmonary barotrauma, decompression sickness or death among divers with asthma. This evidence only accounts for asthmatics with mild disease and the actual risk for severe or uncontrolled asthmatics, may be higher.[11]

Cancers

Cancers are generally considered a class of abnormal, fast growing and disordered cells which have the potential to spread to other parts of the body. They may occur in virtually any organ or tissue. The effect of a cancer on fitness to dive can vary considerably, and will depend on several factors. If the cancer or the treatment compromise the diver's ability to perform the normal activities associated with diving, including the necessary physical fitness, and particularly cancers or treatments which compromise fitness to withstand the pressure changes, then the diver should abstain from diving until passed as fit by a diving medical practitioner who is aware of the condition. Specific considerations include whether the tumour or treatment affects organs which are directly affected by pressure changes, whether the person's capacity to manage themself in and emergency is compromised, including mental awareness and judgement, and that diving should not aggravate the disease. Some cancers, such as lung cancer would be an absolute contraindication. [12]

Diabetes

Like asthma, the traditional medical response to diabetes was to declare the person unfit to dive, but in a similar way, a significant number of divers with well-managed diabetes have logged sufficient dives to provide statistical evidence that it can be done at acceptable risk, and the recommendations of diving medical researchers and insurers has changed accordingly.[13][14]

Current (2016) medical opinion of Divers Alert Network (DAN) and the Diving Diseases Research Centre (DDRC) is that diabetics should not dive if they have any of the following complications:

- Significant retinopathy increases risk of retinal hemorrhage due to minor mask squeeze or equalizing procedures.[13][14]

- Peripheral vascular disease and/or neuropathy increase risk of sudden death due to coronary artery disease,[14]

- Significant autonomic or peripheral neuropathy increases the risk of exaggerated hypotension when leaving the water.[14]

- Nephropathy causing proteinuria[13][14]

- Coronary artery disease [13][14]

- Significant peripheral vascular disease may reduce inert gas washout and predispose the diver to limb decompression sickness.[13][14]

DAN makes the following recommendations for additional precautions by diabetic divers:

- Diabetic divers are advised not to dive deeper than 30 msw (100 fsw), to avoid situations where nitrogen narcosis could be confused with hypoglycemia, for longer than one hour, to limit the time blood glucose levels would remain unmonitored, or to incur compulsory decompression stops, or dive in overhead environments, both of which make direct and immediate access to the surface unavailable.[14]

- Diabetic diver's buddy or dive leader who is informed of their condition and knows the appropriate response in the event of a hypoglycemic episode. It is also recommended the buddy does not have diabetes.[13][14]

- Diabetic divers should avoid circumstances that increase risk of hypoglycemic episodes such as prolonged cold and strenuous dives.[14]

Pregnancy

A study investigating potential links between diving while pregnant and fetal abnormalities by evaluating field data showed that most women are complying with the diving industry recommendation and refraining from diving while pregnant. There were insufficient data to establish significant correlation between diving and fetal abnormalities, and differences in placental circulation between humans and other animals limit the applicability of animal research for pregnancy and diving studies.[15]

The literature indicates that diving during pregnancy does increase the risk to the fetus, but to an uncertain extent. As diving is an avoidable risk for most women, the prudent choice is to avoid diving while pregnant. However, if diving is done before pregnancy is recognised, there is generally no indication for concern.[16]

In addition to possible risk to the fetus, changes in a woman’s body during pregnancy might make diving more problematic. There may be problems fitting equipment and the associated hazards of ill fitting equipment. Swelling of the mucous membranes in the sinuses could make ear clearing difficult, and nausea may increase discomfort.[16]

Diving after childbirth

Divers who want to return to diving after having a child should generally follow the guidelines suggested for other sports and activities, as diving requires a similar level of conditioning and fitness.

After a vaginal delivery, without complications, three weeks is usually sufficient to allow the cervix to close, which reduces the risk of uterine infection. Divers Alert Network recommends as a rule of thumb, to wait four weeks after normal delivery before resuming diving, and at least eight weeks after cesarean delivery. Any complications may indicate a longer wait, and medical clearance is advised.[17]

Physical disabilities

Divers with physical disabilities may be less constrained in their ability to function underwater than on land. Difficulties with access can often be managed, and the partially disabled diver may find the activity a welcome improvement to quality of life. Some constraints can be expected, depending on severity. In many cases equipment can be modified and prosthetics adapted for underwater use. Recreational diving has been used for occupational therapy of otherwise fit people.

Patent foramen ovale

A patent foramen ovale (PFO), or atrial shunt can potentially cause a paradoxical gas embolism by allowing venous blood containing what would normally be asymptomatic inert gas decompression bubbles to shunt from the left atrium to the right atrium during exertion, and can be then circulated to the vital organs where an embolism may form and grow due to local tissue supersaturation during decompression. This congenital condition is found in roughly 25% of adults, and is not listed as a disqualifier from diving, and is not listed as a required medical test for professional of recreational divers. Some training organisations recommend that divers contemplating technical diver training should have themselves tested as a precaution, and to allow informed consent to assume the associated risks.[18]

Psychological fitness to dive

Psychological profiles indicating intelligence and below average neuroticism tend to correlate with successful diving activity over the long term. These divers tend to be self-sufficient and emotionally stable, and less likely to be involved in accidents unrelated to health problems. Nevertheless, many people with mild neuroses can and do dive with an acceptable safety record.[19]

Besides any risks caused by the condition itself, there may be hazards due to the effects of medications taken to manage the condition, either singly or in combination. There are no scientific studies into the safety of diving with most medications, and in most cases the effects of the medication are secondary to the effects of the underlying condition. Drugs with strong effects on moods should be used with care when diving.[19]

A mild state of anxiety can improve performance by making the person more alert and quicker to react, but more severe levels can degrade performance,by narrowing focus and distracting attention, culminating in extreme and debilitating anxiety or panic, where rational response to a developing emergency is lost.[20]

A tendency to be generally anxious is known as trait anxiety, as opposed to anxiety brought on by a situation, which is termed state anxiety. Divers who are prone to trait anxiety are more likely to mismanage a developing emergency by panicking and missing the opportunity to recover from the initial incident.[21] Training can help a diver to recognise rising stress levels, and allow them to take corrective action before the situation deteriorates into an injury or fatality. Over-learning appropriate responses to predictable and reasonably foreseeable contingencies allows the diver to react confidently and effectively, which reduces stress as the positive consequences of the appropriate actions are apparent, usually allowing the diver to terminate the dive in a controlled and safe manner.[22]

Statistics from incidents where the circumstances are known implicate panic and inappropriate response in a large proportion of fatalities and near misses.[23] In 1998 the Recreational Scuba Training Council listed “a history of panic disorder” as an absolute contraindication to scuba diving, but the 2001 guideline specifies “a history of untreated panic disorder” as a severe risk condition, which suggests that some people who are being treated for the condition might dive at an acceptable level of risk.[23]

Recreational scuba diving may be considered an extreme sport since personal risk is involved.[24]

Limited research into the personality characteristics of people choosing to start recreational diving indicate tendencies of self-sufficiency, boldness and impulsiveness (and low scores on conformity, warmth and sensitivity), and are not typical of the personality profiles expected from extreme athletes. Four prevalent personality types were identified, and the results suggested that the risk behaviour of the diver would probably depend on the personality type.[24]

Personality types identified were:[24]

- The adventurer, a focused and enthusiastic person who appears easy to get along with, but has a tendency to be competitive and seek attention, and may take risks that endanger themselves and their diving partners.

- The rationalist, an intelligent person with strong control of their emotional life and general behaviour, who will conform when the situation requires it, and will generally persist until they have mastered the necessary skills, will comply with rational rules and procedures, and follow the instructions of people who appear to be competent. They are unlikely to take unnecessary risks.

- The dreamer, a person who appears to be unconcerned with everyday matters, or absent minded, and take part in scuba diving as an escape from a bland existence to a more exotic world. Once they recognise the challenges of the activity they may become excessively dependent on the instructor or diving partner and may feel insecure and overwhelmed and frequently seek confirmation of their abilities, which may be annoying.

- The passive-aggressive macho diver, a person who initially presents themself as friendly and pleasant, but as they integrate with the group, start to display consistently critical attitudes towards anyone who may be conceived of as less expert than themselves, whether or not this is objectively realistic. This has been explained as a defense mechanism to disguise their underlying insecurity and an attempt to boost their low self-esteem.

Studies of the personality traits of navy divers have indicated that although they operate in a military environment, navy divers tend to be non-conformists.[24]

In a comparison between navy and civilian divers, navy divers scored higher than navy non-divers and civilian divers on calmness and self-control in difficult circumstances and were more emotionally controlled and adventurous, less assertive, more practical, more self-controlled and more likely to follow rules and procedures precisely and work together as a team.[24][25] The navy divers were found to be willing to accept higher risk, and to have a strong sense of control and acceptance of taking personal responsibility for events.[26]

Effects of drugs

The use of medical and recreational drugs, can also influence fitness to dive, both for physiological and behavioural reasons. In some cases prescription drug use may have a net positive effect, when effectively treating an underlying condition, but frequently the side effects of effective medication may have undesirable influences on the fitness of diver, and most cases of recreational drug use result in an impaired fitness to dive, and a significantly increased risk of sub-optimal response to emergencies.

Prescription and non-prescription medication

There are no specific studies that give objective values for the effects and risks of most medications if used while diving, and their interactions with the physiological effects of diving. Any advice given by a medical practitioner is based on educated (to a greater or lesser extent), but unproven assumption, and each case is best evaluated by an expert.[27]

Personality differences between divers will cause each to respond differently to the effects of various breathing gases under pressure and abnormal physiological states. Some of the diving disorders can present symptoms similar to those of psychoneurotic reactions or an organic cerebral syndrome. When considering allowing or barring someone with psychological problems to dive, the certifying physician must be aware of all the possibilities and variations in the specific case.[27]

In many cases an acute illness is best treated in the absence of potential complications caused by diving, but chronic afflictions may require medication if the sufferer is to dive at all. Some of the medication types which are commonly or occasionally known to be used by active divers are listed here, along with possible side effects and complications:[27]

- Motion sickness

- Antihistamines, which include cyclizine, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, and meclizine are the most commonly used medications. They are generally available without a prescription, and have similar side effects, the most common of which is drowsiness, which can adversely affect a diver's situational awareness and reaction speed. There are also other side effects.[28]

- promethazine is chemically related to the tranquilizers, and it also has antihistamine properties. It is generally a prescription drug and drowsiness is a significant side effect, and it may significantly impair ability to perform essential tasks under stressful conditions.[28]

- Trans-dermal scopolamine[28]

- Phenytoin[28]

- Tablet form of scopolamine, by prescription[29]

- Malaria [30]

- Mefloquine

- Doxycycline

- Malarone (a combination of atovaquone and proguanil)

- Chloroquine

- Hydroxychloroquine sulfate

- Pyrimethamine

- Fansidar (sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine)

- No interactions between antimalarial drugs and diving have been established, and complications are not generally expected, but the use of Mefloquine is not accepted by all diving medicine specialists.

- Antimalarial drug prophylaxis recommendations depend on specific regions and may change over time. Current recommendations should be checked.

- All of these drugs may have side-effects, and there are known interactions with other drugs.

- Decongestants [31]

- Contraceptives

- Anxiety, phobias & panic disorders[21]

- Diabetes

- Asthma

- Indigestion

- Headaches

- Cardiovascular and hypertension medication;[32]

- Beta blockers

- ACE inhibitors (Angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors)

- Calcium channel blockers

- Diuretics

- Antiarrhythmics

- Anticoagulants

- Schizophrenia [27]

- Antiinflammatories

Recreational drugs and substance abuse

- Smoking (tobacco)

- Alcohol

- Cannabis

See also

References

- ↑ Williams, G.; Elliott, DH.; Walker, R.; Gorman, DF.; Haller, V. (2001). "Fitness to dive: Panel discussion with audience participation". Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. SPUMS. 31 (3). Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Joint Medical Subcommittee of ECHM and EDTC (24 June 2003). Wendling, Jürg; Elliott, David; Nome, Tor, eds. Fitness to Dive Standards - Guidelines for Medical Assessment of Working Divers (PDF). pftdstandards edtc rev6.doc (Report). European Diving Technology Committee. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ Richardson, Drew. "The RSTC Medical statement and candidate screening model; discussion". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society (SPUMS) Journal Volume 30 No.4 December 2000. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. pp. 210–213. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ Elliott, D. (2000), "Why fitness? Who benefits from diver medical examinations?", Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society., 30 (4), retrieved 2013-04-07

- 1 2 "Dive Standards & Medical Statement". World Recreational Scuba Training Council. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "Importance of Diving Medicals | Medoccs International". medoccs.com. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ Richardson, Drew. "The RSTC Medical statement and candidate screening model". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society (SPUMS) Journal Volume 30 No.4 December 2000. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. pp. 210–213. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "Diving Regulations 2009 of the South African Occupational Health and Safety Act, 1993", Government notice R41, Government Gazette, Pretoria: Government Printer (#32907), 29 January 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vorosmarti, J,; Linaweaver, PG., eds. (1987). Fitness to Dive. 34th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop. UHMS Publication Number 70(WS-WD)5-1-87. (Report). Bethesda: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. p. 116. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Edmonds, Thomas, McKenzie and Pennefather (2010). Diving Medicine for Scuba Divers (3rd ed.). Carl Edmonds.

- 1 2 Adir, Yochai; Bove, Alfred A. (2016). Yochai Adir and Alfred A. Bove, eds. "Can asthmatic subjects dive?" (PDF). Number 1 in the Series "Sports-related lung disease". European Respiratory Review. pp. 214–220. doi:10.1183/16000617.0006-2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ DAN medical team (10 April 2017). "Diving with cancer". DAN Southern Africa. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Staff (2016). "Diving and diabetes". Diver Health. Plymouth, UK.: Diving Diseases Research Centre - DDRC Healthcare. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pollock NW, Uguccioni DM, Dear GdeL, eds. (2005). "Guidelines to Diabetes & Recreational Diving" (PDF). Diabetes and recreational diving: guidelines for the future. Proceedings of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society/Divers Alert Network 2005 June 19 Workshop. Durham, NC: Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ St Leger Dowse, M.; Gunby, A.; Moncad, R.; Fife, C.; Bryson, P. (2006). "Scuba diving and pregnancy: Can we determine safe limits?". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Taylor and Francis. 26 (6): 509–513. doi:10.1080/01443610600797368. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- 1 2 Held, Heather E; Pollock, Neal W. (2007). "The Risks of Pregnancy and Diving". DAN Medical articles. Durham, NC.: Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ DAN medical team (June 2016). "Return to Diving After Giving Birth". DANSA website. Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ↑ Caruso, James L (2006). "The Pathologist's Approach to SCUBA Diving Deaths". American Society for Clinical Pathology Teleconference. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- 1 2 Campbell, Ernest (2000). "Medical info: Psychological Issues in Diving". www.diversalertnetwork.org. Retrieved 11 November 2017. From the September/October 2000 issue of Alert Diver.

- ↑ Yarbrough, John R. "Anxiety: Is It A Contraindication to Diving?". www.diversalertnetwork.org. Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- 1 2 Campbell, Ernest. "Medical info: Psychological Issues in Diving II - Anxiety, Phobias in Diving". www.diversalertnetwork.org. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ Lock, Gareth (8 May 2011). Human factors within sport diving incidents and accidents: An Application of the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) (PDF). Cognitas Incident Management Limited. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- 1 2 Colvard, David F.; Colvard, Lynn Y. (2003). "A Study of Panic in Recreational Scuba Divers". The Undersea Journal. PADI.com. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coetzee, Nicoleen (December 2010). "Personality profiles of recreational scuba divers". African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance. 16 (4): 568–579. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ↑ van Wijk, C. (2002). "Comparing personality traits of navy divers, navy non-divers and civilian sport divers". Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ↑ Krooss, Barbara. "Going Deeper - Medical and Psychological Aspects of Diving With Disabilities". Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Campbell, Ernest. "Medical info: Psychological Issues in Diving III - Schizophrenia, Substance Abuse". www.diversalertnetwork.org. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Mebane, G.Yancey (April 1995). "Motion Sickness". Alert Diver. Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ Kincade, Dan (October 2003). "Motion Sickness - Updated 2003". Alert diver. Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ Leigh, Dan (September 2002). "DAN Discusses Malaria and Antimalarial Drugs". Alert Diver. Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ Thalmann, E.D. (December 1999). "Pseudoephedrine & Enriched-Air Diving?". Alert diver. Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ Gowen, Laurie (2005). "Cardiovascular Medications and Diving". Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 15 November 2017. First published in Alert Diver November/December 2005