Avascular necrosis

| Avascular necrosis | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Osteonecrosis,[1] bone infarction,[2] aseptic necrosis,[1] ischemic bone necrosis[1] |

| |

| Head of the femur showing a flap of cartilage due to avascular necrosis (osteochondritis dissecans). Specimen removed during total hip replacement surgery. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Joint pain, decreased ability to move[1] |

| Complications | Osteoarthritis[1] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[1] |

| Risk factors | Bone fractures, joint dislocations, alcoholism, high dose steroids[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging, biopsy[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Osteopetrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Legg-Calve-Perthes syndrome, sickle cell disease[3] |

| Treatment | Medication, not walking on the affected leg, stretching, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | ~15,000 per year (US)[4] |

Avascular necrosis (AVN), also called osteonecrosis or bone infarction, is death of bone tissue due to interruption of the blood supply.[1] Early on there may be no symptoms.[1] Gradually joint pain may develop which may limit the ability to move.[1] Complication may include collapse of the bone or nearby joint surface.[1]

Risk factors include bone fractures, joint dislocations, alcoholism, and the use of high-dose steroids.[1] The condition may also occur without any clear reason.[1] The most commonly affected bone is the femur.[1] Other relatively common sites include the upper arm bone, knee, shoulder, and ankle.[1] Diagnosis is typically by medical imaging such as X-ray, CT scan, or MRI.[1] Rarely biopsy may be used.[1]

Treatments may include medication, not walking on the affected leg, stretching, and surgery.[1] Most of the time surgery is eventually required and may include core decompression, osteotomy, bone grafts, or joint replacement.[1] About 15,000 cases occur per year in the United States.[4] People 30 to 50 years old are most commonly affected.[3] Males are more commonly affected than females.[4]

Signs and symptoms

In many cases there is pain and discomfort in a joint which increases over time. While it can affect any bone, about half of cases show multiple sites of damage.[5] Avascular necrosis primarily affects the joints at the shoulder, knee, and hip. The classical sites are: head of femur, neck of talus and waist of the scaphoid.

Avascular necrosis most commonly affects the ends of long bones such as the femur (the bone extending from the knee joint to the hip joint). Other common sites include the humerus (the bone of the upper arm),[6][7] knees,[8][9] shoulders,[6][7] ankles and the jaw.[10]

Causes

The main risk factors are bone fractures, joint dislocations, alcoholism, and the use of high dose steroids.[1] Other risk factors include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and organ transplantation.[1] Osteonecrosis is also associated with cancer, lupus, sickle cell disease, HIV infection, Gaucher’s disease, and Caisson disease.[1] The condition may also occur without any clear reason.[1]

Bisphosphonates are associated with osteonecrosis of the mandible.[11] Prolonged, repeated exposure to high pressures (as experienced by commercial and military divers) has been linked to AVN, though the relationship is not well understood.

Pathophysiology

The hematopoietic cells are most sensitive to low oxygen and are the first to die after reduction or removal of the blood supply, usually within 12 hours.[2] Experimental evidence suggests that bone cells (osteocytes, osteoclasts, osteoblasts etc.) die within 12–48 hours, and that bone marrow fat cells die within 5 days.[2]

Upon reperfusion, repair of bone occurs in 2 phases. First, there is angiogenesis and movement of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells from adjacent living bone tissue grow into the dead marrow spaces, as well as entry of macrophages that degrade dead cellular and fat debris.[2] Second, there is cellular differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts or fibroblasts.[2] Under favorable conditions, the remaining inorganic mineral volume forms a framework for establishment of new, fully functional bone tissue.[2]

Diagnosis

In the early stages, bone scintigraphy and MRI are the preferred diagnostic tools.[12][13]

X-ray images of avascular necrosis in the early stages usually appear normal. In later stages it appears relatively more radio-opaque due to the nearby living bone becoming resorbed secondary to reactive hyperemia.[2] The necrotic bone itself does not show increased radiographic opacity, as dead bone cannot undergo bone resorption which is carried out by living osteoclasts.[2] Late radiographic signs also include a radiolucency area following the collapse of subchondral bone (crescent sign) and ringed regions of radiodensity resulting from saponification and calcification of marrow fat following medullary infarcts.

Radiography of total avascular necrosis of right humeral head. Woman of 81 years with diabetes of long evolution.

Radiography of total avascular necrosis of right humeral head. Woman of 81 years with diabetes of long evolution. Radiography of avascular necrosis of left femoral head. Man of 45 years with AIDS.

Radiography of avascular necrosis of left femoral head. Man of 45 years with AIDS. Nuclear magnetic resonance of avascular necrosis of left femoral head. Man of 45 years with AIDS.

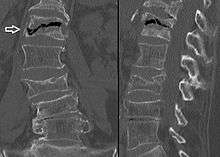

Nuclear magnetic resonance of avascular necrosis of left femoral head. Man of 45 years with AIDS. The intravertebral vacuum cleft sign (at white arrow) is a sign of avascular necrosis. Avascular necrosis of a vertebral body after a vertebral compression fracture is called Kümmel's disease.[14]

The intravertebral vacuum cleft sign (at white arrow) is a sign of avascular necrosis. Avascular necrosis of a vertebral body after a vertebral compression fracture is called Kümmel's disease.[14]

Treatment

A variety of methods may be used to treat[5] the most common being the total hip replacement (THR). However, THRs have a number of downsides including long recovery times and short life spans (of the hip joints). THRs are an effective means of treatment in the older population; however, in younger people they may wear out before the end of a person's life.

Other techniques such as metal on metal resurfacing may not be suitable in all cases of avascular necrosis; its suitability depends on how much damage has occurred to the femoral head.[15] Bisphosphonates which reduces the rate of bone breakdown may prevent collapse (specifically of the hip) due to AVN.[16]

Core decompression

Other treatments include core decompression, where internal bone pressure is relieved by drilling a hole into the bone, and a living bone chip and an electrical device to stimulate new vascular growth are implanted; and the free vascular fibular graft (FVFG), in which a portion of the fibula, along with its blood supply, is removed and transplanted into the femoral head.[17] A 2012 Cochrane systematic review noted that no clear improvement can be found between people who have had hip core decompression and participate in physical therapy, versus physical therapy alone. More research is need to look into the effectiveness of hip core decompression for people with sickle cell disease.[18]

Progression of the disease could possibly be halted by transplanting nucleated cells from bone marrow into avascular necrosis lesions after core decompression, although much further research is needed to establish this technique.[19][20]

Prognosis

The amount of disability that results from avascular necrosis depends on what part of the bone is affected, how large an area is involved, and how effectively the bone rebuilds itself. The process of bone rebuilding takes place after an injury as well as during normal growth.[15] Normally, bone continuously breaks down and rebuilds—old bone is resorbed and replaced with new bone. The process keeps the skeleton strong and helps it to maintain a balance of minerals.[15] In the course of avascular necrosis, however, the healing process is usually ineffective and the bone tissues break down faster than the body can repair them. If left untreated, the disease progresses, the bone collapses,[21] and the joint surface breaks down, leading to pain and arthritis.[1]

Epidemiology

Avascular necrosis usually affects people between 30 and 50 years of age; about 10,000 to 20,000 people develop avascular necrosis of the head of the femur in the US each year. When it occurs in children at the femoral head, it is known as Legg-Calvé-Perthes syndrome.[22]

Society and culture

Cases of avascular necrosis have been identified in a few high profile athletes. It abruptly ended the career of American football running-back Bo Jackson in 1991. Doctors discovered Jackson to have lost all of the cartilage supporting his hip while he was undergoing tests following a hip-injury he had on the field during a 1991 NFL Playoff game.[23] Avascular necrosis of the hip was also identified in a routine medical check-up on quarterback Brett Favre following his trade to the Green Bay Packers in 1991.[24] However, Favre would go on to have a long career at the Packers.

Another high profile athlete was American road racing cyclist Floyd Landis,[25] winner of the 2006 Tour De France, the title being subsequently stripped from his record by cycling's governing bodies after his blood samples tested positive for banned substances.[26] During that tour, Landis was allowed cortisone shots to help manage his ailment, despite cortisone also being a banned substance in professional cycling at the time.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "Questions and Answers about Osteonecrosis (Avascular Necrosis)". NIAMS. October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 eMedicine Specialties > Bone Infarct Archived 4 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Author: Ali Nawaz Khan. Coauthors: Mohammed Jassim Al-Salman, Muthusamy Chandramohan, Sumaira MacDonald, Charles Edward Hutchinson

- 1 2 "Osteonecrosis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2009. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 166. ISBN 9780323529570. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017.

- 1 2 National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (March 2006). "Osteonecrosis". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- 1 2 Chapman, C; Mattern, C; Levine, Wn (Nov 2004). "Arthroscopically assisted core decompression of the proximal humerus for avascular necrosis". Arthroscopy. 20 (9): 1003–1006. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2004.07.003. ISSN 0749-8063. PMID 15525936.

- 1 2 Mansat, P; Huser, L; Mansat, M; Bellumore, Y; Rongières, M; Bonnevialle, P (Mar 2005). "Shoulder arthroplasty for atraumatic avascular necrosis of the humeral head: nineteen shoulders followed up for a mean of seven years". Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 14 (2): 114–120. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.06.019. ISSN 1058-2746. PMID 15789002.

- ↑ Jacobs, Ma; Loeb, Pe; Hungerford, Ds (Aug 1989). "Core decompression of the distal femur for avascular necrosis of the knee". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 71 (4): 583–7. ISSN 0301-620X. PMID 2768301.

- ↑ Bergman, Nr; Rand, Ja (Dec 1991). "Total knee arthroplasty in osteonecrosis" (Free full text). Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (273): 77–82. doi:10.1097/00003086-199112000-00011. ISSN 0009-921X. PMID 1959290.

- ↑ Baykul, T; Aydin, Ma; Nasir, S (Nov 2004). "Avascular necrosis of the mandibular condyle causing fibrous ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint in sickle cell anemia". The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 15 (6): 1052–1056. doi:10.1097/00001665-200411000-00035. ISSN 1049-2275. PMID 15547404.

- ↑ Dannemann, C; Grätz, Kw; Riener, Mo; Zwahlen, Ra (Apr 2007). "Jaw osteonecrosis related to bisphosphonate therapy: a severe secondary disorder". Bone. 40 (4): 828–834. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.023. ISSN 8756-3282. PMID 17236837.

- ↑ Maillefert, Jf; Toubeau, M; Piroth, C; Piroth, L; Brunotte, F; Tavernier, C (Jun 1997). "Bone scintigraphy equipped with a pinhole collimator for diagnosis of avascular necrosis of the femoral head". Clinical rheumatology. 16 (4): 372–377. doi:10.1007/BF02242454. ISSN 0770-3198. PMID 9259251.

- ↑ Bluemke, Da; Zerhouni, Ea (Aug 1996). "MRI of avascular necrosis of bone". Topics in magnetic resonance imaging : TMRI. 8 (4): 231–46. doi:10.1097/00002142-199608000-00003. ISSN 0899-3459. PMID 8870181.

- ↑ Freedman, B. A.; Heller, J. G. (2009). "Kummel Disease: A Not-So-Rare Complication of Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures". The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 22 (1): 75–78. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080100. ISSN 1557-2625.

- 1 2 3 Hall, [edited by] Brian K. (15 November 1989). Bone. CRC Press. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-0-936923-24-6. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Agarwala, S; Jain, D; Joshi, Vr; Sule, A (Mar 2005). "Efficacy of alendronate, a bisphosphonate, in the treatment of AVN of the hip. A prospective open-label study" (Free full text). Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 44 (3): 352–359. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh481. ISSN 1462-0324. PMID 15572396.

- ↑ Judet, H; Gilbert, A (May 2001). "Long-term results of free vascularized fibular grafting for femoral head necrosis" (Free full text). Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 386 (386): 114–9. doi:10.1097/00003086-200105000-00015. ISSN 0009-921X. PMID 11347824.

- ↑ Martí-Carvajal, Arturo J.; Solà, Ivan; Agreda-Pérez, Luis H. (2012-05-16). "Treatment for avascular necrosis of bone in people with sickle cell disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD004344. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004344.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 22592696.

- ↑ Gangji V, Hauzeur JP (March 2005). "Treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head with implantation of autologous bone-marrow cells. Surgical technique". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 87 Suppl 1 (Pt 1): 106–112. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02662. PMID 15743852. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009.

- ↑ Lieberman, Jay R; Conduah, Augustine; et al. (December 2004). "Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head with Core Decompression and Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 429: 139–145. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000150312.53937.6f. PMID 15577478.

- ↑ Digiovanni, Cw; Patel, A; Calfee, R; Nickisch, F (Apr 2007). "Osteonecrosis in the foot". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 15 (4): 208–17. ISSN 1067-151X. PMID 17426292.

- ↑ Gross, Gw; Articolo, Ga; Bowen, Jr (1999). "Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease: Imaging Evaluation and Management". Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. 3 (4): 379–390. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1080081. ISSN 1089-7860. PMID 11388931.

- ↑ Altman, Lawrence K. "Jackson's Case Is Dividing The Doctors".

- ↑ "JS Online:What, his hip? Favre reveals he has avascular necrosis". 27 September 2006.

- ↑ "What He's Been Pedaling", The New York Times, July 16, 2006.

- ↑ "Landis Tests Positive; Title is a total complete loss". Chicago Tribune. 2006-08-05.

- ↑ Fotheringham, Alasdair (2006-07-24). "Cycling: Landis the Tour king celebrates a triumph of survival". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2006-08-06. Retrieved 2006-07-28. (subscription required)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Osteonecrosis / Avascular Necrosis at the National Institute of Health

- Osteonecrosis / Avascular necrosis at Merck Manual for patients

- Osteonecrosis / Avascular necrosis at Merck Manual for medical professionals