Propionic acidemia

| Propionic acidemia | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Hyperglycinemia with ketoacidosis and leukopenia |

| |

| Propionic acid | |

| Specialty |

Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Poor muscle tone, lethargy, vomiting |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing; high levels of propionic acid in the urine |

| Treatment | Low-protein diet |

| Prognosis | Development may be normal, or patients may have lifelong learning disabilities |

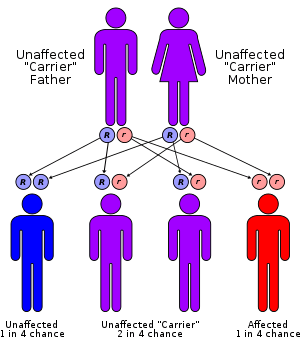

Propionic acidemia, also known as propionic aciduria, propionyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency (PCC deficiency) and ketotic glycinemia,[1] is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder, classified as a branched-chain organic acidemia.[2][3]

The disorder presents in the early neonatal period with poor feeding, vomiting, lethargy, and lack of muscle tone.[4] Death can occur quickly, due to secondary hyperammonemia, infection, cardiomyopathy, or basal ganglial stroke.[5]

History

In 1957, a male child was born with poor mental development, repeated attacks of acidosis, and high levels of ketones and glycine in the blood. Upon dietary testing, Dr. Barton Childs discovered that his symptoms worsened when given the amino acids leucine, isoleucine, valine, methionine, and threonine. In 1961, the medical team at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland published the case, calling the disorder ketotic hyperglycenemia. In 1969, using data from the original patient's sister, scientists discovered that propionic academia was a recessive disorder, and that propionic academia and methylmalonic acidemia are caused by deficiencies in the same enzyme pathway. [6]

Symptoms

Propionic acidemia is characterized almost immediately in newborns. Symptoms include poor feeding, vomiting, dehydration, acidosis, low muscle tone (hypotonia), seizures, and lethargy. The effects of propionic acidemia quickly become life-threatening.

Pathophysiology

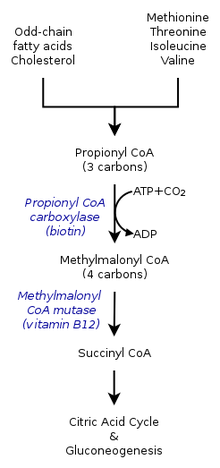

In healthy individuals, the enzyme propionyl-CoA carboxylase converts propionyl-CoA to methylmalonyl-CoA. This is one step in the process of converting certain amino acids and fats into sugar for energy. Individuals with PA cannot perform this conversion because the enzyme propionyl-CoA carboxylase is nonfunctional. The essential amino acids valine, methionine, isoleucine, and threonine, as well as odd-chain fatty acids (hence the mnemonic "VOMIT"), are simply converted to propionyl-CoA, before the process stops, leading to a buildup of propionyl-CoA. Instead of being converted to methylmalonyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA is then converted into propionic acid, which builds up in the bloodstream. This in turn causes an accumulation of dangerous acids and toxins, which can cause damage to the organs.

In many cases, PA can damage the brain, heart, and liver, cause seizures, and delays to normal development like walking and talking. During times of illness the affected person may need to be hospitalized to prevent breakdown of proteins within the body. Each meal presents a challenge to those with PA. If not constantly monitored, the effects would be devastating. Dietary needs must be closely managed by a metabolic geneticist or metabolic dietician.

Mutations in both copies of the PCCA or PCCB genes cause propionic acidemia.[7] These genes are responsible for the formation of the enzyme propionyl-CoA carboxylase (EC 6.4.1.3), referred to as PCC.

PCC is required for the normal breakdown of the essential amino acids valine, isoleucine, threonine, and methionine, as well as certain odd-chained fatty-acids. Mutations in the PCCA or PCCB genes disrupt the function of the enzyme, preventing these acids from being metabolized. As a result, propionyl-CoA, propionic acid, ketones, ammonia, and other toxic compounds accumulate in the blood, causing the signs and symptoms of propionic acidemia.

Diagnosis

Elevated blood propionic acid levels, with normal biotin levels.

Management

Patients with propionic acidemia should be started as early as possible on a low protein diet. In addition to a protein mixture that is devoid of methionine, threonine, valine, and isoleucine, the patient should also receive L-carnitine treatment and should be given antibiotics 10 days per month in order to remove the intestinal propiogenic flora. The patient should have diet protocols prepared for him with a “well day diet” with low protein content, a “half emergency diet” containing half of the protein requirements, and an “emergency diet” with no protein content. These patients are under the risk of severe hyperammonemia during infections that can lead to comatose states.[8]

Liver transplant is gaining a role in the management of these patients, with small series showing improved quality of life.

Epidemiology

Propionic acidemia is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern and is found in about 1 in 35,000[7] live births in the United States. The condition appears to be more common in Saudi Arabia,[9] with a frequency of about 1 in 3,000.[7] The condition also appears to be common in Amish, Mennonite and other populations where inbreeding is common.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 606054

- ↑ Ravn K; Chloupkova M; Christensen E; Brandt NJ; Simonsen H; Kraus JP; Nielsen IM; Skovby F; Schwartz M (July 2000). "High incidence of propionic acidemia in greenland is due to a prevalent mutation, 1540insCCC, in the gene for the beta-subunit of propionyl CoA carboxylase". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (1): 203–206. doi:10.1086/302971. PMC 1287078. PMID 10820128.

- ↑ Deodato F, Boenzi S, Santorelli FM, Dionisi-Vici C (2006). "Methylmalonic and propionic aciduria". Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 142 (2): 104–112. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30090. PMID 16602092.

- ↑ "Propionic acidemia". National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. 2 Dec 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ Hamilton RL, Haas RH, Nyhan WC, Powell HC, Grafe MR (1995). "Neuropathology of propionic acidemia: a report of two patients with basal ganglia lesions". Journal of Child Neurology. 10 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1177/088307389501000107. PMID 7769173.

- ↑ Hsia, T. (2003). "How Ketotic Hyperglycinemia Became Propionic Acidemia" (PDF). Paresearch.org. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/barry_lab/ropionic-Aciademia.cfm Archived 2008-08-29 at the Wayback Machine.

Barry Lab - Vector and Virus Engineering. Gene therapy for Propionic Acidemia - ↑ Saudubray JM, Van Der Bergh G, Walter J : Inborn Metabolic Diseases Diagnosis and Treatment (2012)

- ↑ Al-Odaib AN, Abu-Amaro KK, Ozand PT, Al-Hellani AM (2003). "A new era for preventive genetic programs in the Arabian Peninsula". Saudi Medical Journal. 24 (11): 1168–1175. PMID 14647548.

- ↑ Kidd JR, Wolf B, Hsia E, Kidd KK (1980). "Genetics of propionic acidemia in a Mennonite-Amish kindred". Am J Hum Genet. 32 (2): 236–245. PMC 1686010. PMID 7386459.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Propionic acidemia at NLM Genetics Home Reference

- Propionic acidemia at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- "Propionic acidemia". Orphanet.