Portobello, Edinburgh

Portobello

| |

|---|---|

Portobello Beach | |

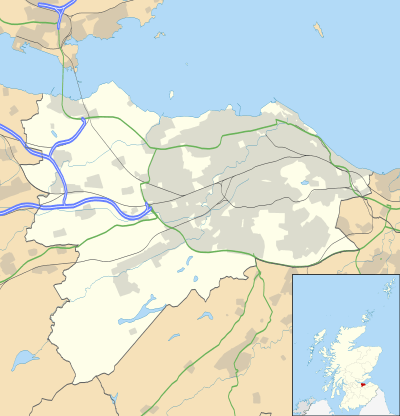

Portobello Portobello shown within Edinburgh | |

| OS grid reference | NT304738 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | EDINBURGH |

| Postcode district | EH15 |

| Dialling code | 0131 |

| Police | Scottish |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| EU Parliament | Scotland |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Portobello is a coastal suburb of Edinburgh. It lies in eastern central Scotland, three miles (5 km) to the east of Edinburgh city centre, facing the Firth of Forth, between the suburbs of Joppa and Craigentinny. Although historically it was a town in its own right and is often still felt to be such, it is officially a residential suburb of Edinburgh. The promenade fronts onto a wide sandy beach.

History

The area was originally known as Figgate Muir, an expanse of moorland through which the Figgate Burn flowed as the Braid Burn continuation to the sea, with a broad sandy beach on the Firth of Forth. The name Figgate was thought to come from the Saxon term for "cow's ditch". The land was used as pasture for cattle by the monks of Holyrood Abbey and the name is more likely to mean "cow road" as in Cowgate in Edinburgh.[1] In 1296, William Wallace mustered forces on the moor in a campaign that led to the Battle of Dunbar, and in 1650 it was the supposed scene of a secret meeting between Oliver Cromwell and Scottish leaders. A report from 1661 describes a race in which twelve browster-wives ran from the Burn (recorded as the Thicket Burn) to the top of Arthur's Seat.[2]

By the 18th century, it had become a haunt of seamen and smugglers. A cottage was built in 1742 on what is now the High Street (close to the junction with what is now Brighton Place) by a seaman called George Hamilton, who had served under Admiral Edward Vernon during the 1739 capture of Porto Bello, Panama, meaning literally "beautiful port or harbour", and who named the cottage Portobello Hut in honour of that victory. By 1753, there were other houses around it, and the cottage itself remained intact until 1851, becoming a hostelry for walkers and becoming known as the Shepherd's Ha'.[2]

In 1763, the lands known as the Figgate Whins were sold by Lord Milton to Baron Mure for about £1,500, and afterwards feued out by the latter to William Jameson or Jamieson at the rate of £3 per acre. Jameson discovered a valuable bed of clay near the burn, and built a brick and tile works beside the stream. He later built an earthenware pottery factory, and the local population grew so that Portobello became a thriving village.[2] Land values subsequently rose, and by the beginning of the 19th century some parts had been sold at a yearly feu-duty of £40 per annum per acre.[3]

Portobello Sands were used at that time by the Edinburgh Light Horse for drill practice. Walter Scott was their quartermaster, and in 1802 while riding in a charge he was kicked by a horse and confined to his lodgings for three days. While recovering, he finished The Lay of the Last Minstrel.[2] The Scots Magazine in 1806. He noted that the lands were "a perfect waste covered almost entirely with whins or furze". Portobello developed into a fashionable bathing resort, and in 1807 new salt-water baths were erected at a cost of £5,000.[3] In 1822, the visit of King George IV to Scotland, organised by Scott, included a review of troops and Highlanders held on the sands, with spectators crowding the sand dunes.[2]

During the 19th century, Portobello became an industrial town, manufacturing bricks (the "Portobello brick"), glass, lead, paper, pottery, soap, and mustard. Joppa to the east was important in the production of salt.

In 1833, the town was made a burgh, then in 1896 it was incorporated into Edinburgh by Act of Parliament.[4] A formidable red-brick power station (designed by Ebenezer James MacRae) was built in 1934 at the west end of the beach and operated until 1977. It was demolished in the following 18 months.[5]

Between 1846 and 1964, a railway station provided ready access for visitors to the resort, whose facilities came to include a large open-air heated swimming pool, where the actor Sean Connery once worked as a lifeguard. It made use of the power station's waste heat. The pool was closed in 1979. There was also a lido (now demolished) and a permanent funfair which closed in 2007. In 1901, Portobello Baths were opened on The Promenade overlooking the beach. The baths, now known as Portobello Swim Centre, are now home to one of only three remaining operational Turkish baths in Scotland still open to the public.[6]

Portobello Pier was a pleasure pier situated near the end of Bath Street. It operated from 23 May 1871 until the start of World War I. The pier was 1,250 feet (381 m) long and had a restaurant and observatory at the end. It cost £7,000 to build and was designed by Sir Thomas Bouch, who was infamously linked to the Tay Bridge disaster. The iron supports rusted away and the pier was demolished as uneconomic to repair in 1917.

The Edinburgh Marine Gardens were built north of Kings Road in 1908–9. They included an open-air theatre, an industrial hall, a ballroom (later used as a skating rink), a scenic railway, a "rustic mill and water-wheel" and a speedway track. It fell out of use in World War I and never recovered. The speedway/motor cycle track remained in operation until 1939 and the outbreak of World War II. The site was cleared in 1966 and taken over for the Lothian Buses Marine bus depot.

Portobello Town Hall fell into redundancy when Portobello was placed under the jurisdiction of Edinburgh and the building was converted into a cinema in 1912 by Robert Lorimer and Robert Matthew.[7] On the demise of cinemas in the 1970s the building returned to council ownership and was renamed as Portobello Town Hall again. It is a venue for functions but despite its name has no "town hall function".

Portobello Lido was built in 1933.

Extended police and media attention to the July 1983 abduction of young Caroline Hogg from the Promenade area and her murder by Robert Black had a strong impact on the popularity of the area.[8]

Portobello's peak as a resort was in the late 19th century, and it was in slow decline throughout the 20th century. Whilst visitors were primarily drawn from the inhabitants of Edinburgh,[9] it was also once popular with Glaswegians, particularly when the Glasgow Fair "trade holiday" signalled the start of a two-week holiday for the west of Scotland.[10] By the 1960s, it had become an area of amusement arcades and a number of permanent funfair attractions. From the 1980s onwards, these gradually disappeared, and by the end of the 20th century the Promenade had almost no attractions specific to its seaside location (although the Tower Amusements arcade remains in business).

The 21st century has seen the emergence of many community organisations, some specifically focused on the Promenade. The beach hosts regular beach volleyball, including hosting the Olympic beach volleyball qualifiers[11], as well as hosting one of Europe's biggest busking events, the annual Big Beach Busk [12]. Other community organisations are more focused on the sea. These include the "Portobello, Sailing, Kayaking and Rowing Club"[13], Rowporty [14] and Eastern Amateur Coastal Rowing Club.[15] Others have focused on developing community gardens [16] and a monthly local food market [17], while others have focused on youth theatre [18] and culture and music.[19].

SEPA classified the quality of the swimming water as “poor” (Portobello West) and “sufficient” (Portobello Central) in its 2017 and 2018 surveys.[20] Despite this, sightings of dolphins off the coast in 2018 suggests water quality had improved.[21] A wild swimmers' club that has been braving the waves throughout the year since 2010,[22] also suggests this, meanwhile a warmer alternative is provided by the Turkish Baths [23] in Portobello Swim Centre.

In October 2016, Portobello became the first urban community in Scotland to register a Community Right to Buy after the 2016 expansion of Land reform in Scotland to cover urban areas too.[24]. The purchase of Bellfield Old Parish Church and Halls by Action Porty[25] for £600,000 was confirmed by Scottish Government Ministers on 3 May 2017, a purchase partly funded by the Scottish Land Fund and partly by community donations and borrowing. The buildings and grounds were formally passed over from the Church of Scotland to Action Porty on 6th September 2017, and were opened to the community as Bellfield (Community Centre), Portobello on 23rd June 2018.[26]

In 2018 a plan to relay the setts in Brighton Place caused controversy because of the cost of the work and its duration: the road, one of the main routes into Portobello, is due to be closed to all traffic for over a year while the work is completed.[27][28]

Ethnicity

| Portobello compared | Portobello | Edinburgh |

|---|---|---|

| White | 92.6% | 91.7% |

| Asian | 4.8% | 5.5% |

| Black | 1.4% | 1.2% |

| Mixed | 0.7% | 0.9% |

| Other | 0.5% | 0.8% |

Transport

Bus

Portobello is served by Lothian Buses & East Coast Buses, which provides eleven services to the area, continuing towards Joppa and Eastfield to Musselburgh, Port Seton, Tranent or North Berwick, or down Brighton Place to Fort Kinnaird or Royal Infirmary, or from Kings Road to Craigentinny.[29]

Railway

Portobello's first railway station was initially served by the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway. The Portobello (E&DR) railway station operated from 1832 until 1846, when it was replaced by the Portobello (NBR) railway station operated by the North British Railway. The station closed in 1964 as a result of the Beeching cuts.

Hovercraft

For two weeks in 2007 there was an experimental hovercraft service to Kirkcaldy in Fife. Stagecoach was interested in running a regular service, but the local authority refused planning permission for the infrastructure.[30]. Stagecoach planned to use a terminal to be built in Leith using public funds, which failed to materialise.[31]

Notable people

In birth order:

- Dr David Laing LLD (1792–1878), librarian to the Signet Library and noted archaeologist, lived at 12 James Street.

- Mackintosh MacKay (1793–1873), compiler of a Gaelic dictionary and Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, died in Portobello.

- Hugh Miller (1802–1856), a founding father of geology, lived in the tower in Tower Street, where he committed suicide.

- Alan Stevenson (1806–1865), lighthouse engineer, lived his final years at 13 Pittville St, then called Pitt St.[32]

- Stevenson Macadam (1829–1901), scientist and author, lived much of his life in East Brighton Crescent, Portobello.

- William Durham FRSE (1834–1893), chemist, papermaker and astronomer, lived and died at 16 Straiton Place.

- Lucy Bethia Walford, née Colquhoun (1845–1915), novelist, was born in Portobello.

- James Graham Fairley (1846–1934) architect, lived at 47 Abercorn Terrace

- William Ivison Macadam (1856–1902), chemist and antiquarian, spent his childhood in Portobello.

- Alexander Philip (1858–1932), a lawyer born in Portobello, became a campaigner for calendar reform.

- William Robertson (VC) (1865–1949), recipient of the Victoria Cross, lived at 21 Lee Crescent.[33]

- Harry Lauder (1870–1950), music hall entertainer, was born in a tiny cottage at 3 Bridge Street.[34] There is a memorial garden beside the New Town Hall named after him (built in 1912 by architect James A Williamson,[35]) as is Portobello's main bypass, Sir Harry Lauder Road, skirting the area to landward.

- William Russell Flint (1880–1969), painter,[36] lived at 9 Rosefield Place.

- Alexander Heron (1884–1971), member of 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition and Director of the Geological Survey of India (1936–39), lived in Hamilton Terrace in 1900–1911.

- Ned Barnie (1896–1983), born in Portobello, was the first Scot to swim the English Channel, in 1950.

- Norrie Haywood (1910–1979), born in Portobello, became a professional footballer and football manager.

- James Rankin (1913–1975), born in Portobello, was a RAF fighter pilot in World War II.

- George Brown (born 1930), born in Portobello, is a researcher into the field of mental illness.

- Johnny Cunningham (1957–2003), Celtic fiddle virtuoso, was born in Portobello.

- Gail Porter (born 1971), TV presenter, grew up in Portobello, attending Portobello High School.[37][38]

- Ewen Bremner (born 1972), born in Portobello, is a noted film and TV actor.

- Iron Virgin (1970s), glam punk rock band [39]

- Shauna Macdonald (born 1981), actress, grew up in Portobello.[40]

Notable buildings

.jpg)

Notable buildings (now demolished)

Sport

The promenade and beach hosts two annual four-mile (6.4 km) running races. The Portobello Beach Race has been held every summer since 2013;[41] the Promathom has been run almost every New Year's Day since 1987.[42] A weekly 5-km (3.1-mile) Park Run occurs every Saturday in Figgate Park, causing controversy in 2018 in the local press.[43][44]

See also

- For Portobello Cemetery, see Eastfield, Edinburgh.

- Portobello RFC

References

- ↑ "Placenames of Midlothian" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grant, James (1880). "14: Portobello". Old and New Edinburgh. V. London: Cassell & Company Limited. pp. 143–149. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- 1 2 Gilbert, W.M., editor, Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century, Edinburgh, 1901: 45

- ↑ Gilbert, W.M., editor, Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century, Edinburgh, 1901: 176

- ↑ Gifford, John; McWilliam, Colin; Walker, David; Wilson, Christopher, editors, The Buildings of Scotland – Edinburgh, London, 1984: 650, ISBN 0-14-071068-X

- ↑ "VICTORIAN TURKISH BATHS". www.victorianturkishbath.org.

- ↑ Dictionary of Scottish Architects: Robert Lorimer

- ↑ McEwen, Alan (8 July 2013). "Caroline Hogg murder: City scarred 30 years on - The Scotsman". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ McCall, Chris (9 June 2016). "In pictures: Scots enjoy the seaside, now and then". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ Foley, Archie; Monroe, Margaret (6 September 2013). "Portobello & the Great War". Stroud: Amberley Publishing. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "Porty to host Olympic beach volleyball qualifiers". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Portobello Big Beach Busk hailed a huge success". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Portobello, Sailing, Kayaking and Rowing club". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Rowporty". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Eastern Amateur Coastal Rowing Club" (in e). Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Donkeyfield Community Gardens". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Portobello Market". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Portobello Youth Theatre". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Portobello Open Door (POD)". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Revealed: SEPA rank Firth of Forth's best and worst beaches". Retrieved 2018-05-28.

- ↑ "Pod of dolphins spotted off Portobello". Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ↑ "Swimming with the Wild Ones". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Take the plunge at Portobello's Turkish Baths". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Scotland's first urban right to buy". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Action Porty". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Right-to-buy community hub set to open in Portobello church". Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Businesses fear for future as council plan to close Portobello road for a year". Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ↑ "Call for cobble work to be scrapped". BBC News. 2018-06-04. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ↑ Bus map Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ↑ Swanson, Ian (12 January 2017). "Calls for Forth hovercraft service following bridge closure". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Insider site Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ Portobello Post Office Directory 1865

- ↑ Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1911

- ↑ Lauder, Sir Harry, Roamin' in the Gloamin (autobiography) Hutchinson & Co., Ltd, London, 1928, p. 34.

- ↑ Gifford, John; McWilliam, Colin; Walker, David; Wilson, Christopher, eds, The Buildings of Scotland – Edinburgh, London, 1984, p. 653, ISBN 0-14-071068-X ,

- ↑ Stuff, Good. "William Russell Flint black plaque in Edinburgh". www.blueplaqueplaces.co.uk.

- ↑ Porter G., Irish Independent, They told me I'd be crazy to go into TV, , 29 November 2007

- ↑ BBC News website, Porter's star turn at old school, , 2 March 2007

- ↑ "Fame at last for 1970s group... but where are Iron Virgin?".

- ↑ "Movie star Shauna rings in changes for Bellfield". Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- ↑ "Maureen Child Update 20 April 2017 – Portobello Online". porty.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Portobello Promathon Results index". www.salroadrunningandcrosscountrymedalists.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Portobello Parkrun under threat as athletes urinate in street". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Porty parkrun turns nasty after competitive athletes "push child over"". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Edinburgh/East. |