Paleoart

Paleoart (also spelled palaeoart, paleo-art, or paleo art) is any original artistic work that attempts to reconstruct or depict prehistoric life according to the current knowledge and scientific evidence at the time of the artwork's creation.[1] The term "paleoart", which is a portmanteau of "art" and the ancient Greek word for "old", was introduced in the late 1980s by Mark Hallett for art that depicts subjects related to paleontology,[2] but is considered to have originated as a visual tradition in early 1800s England.[3][4] Works of paleoart may be representations of fossil remains or depictions of the living creatures and their ecosystems. While paleoart is typically defined as being scientifically informed, it is also recognized as important in influencing depictions of prehistoric animals in popular culture media, which in turn influences public perception of, and fuels interest in, these animals.[5]

Definitions

A chief driver in the inception of paleoart as a distinct form of scientific illustration was the desire of both the public and of paleontologists to visualize the prehistory that fossils represented.[1] Mark Hallett, who coined the term "paleoart" in 1987, stressed the importance of the cooperative effort between artists, paleontologists and other specialists in gaining access to information for generating accurate, realistic restorations of extinct animals and their environments.[2][6]

Since paleontological knowledge and public perception of the field have changed dramatically since the earliest attempts at reconstructing prehistory, paleoart as a discipline has consequently changed over time as well. This has led to difficulties in creating a shared definition of the term. Given that the drive towards scientific accuracy has always been a salient feature of the discipline, some authors point out the importance of separating true paleoart from "paleoimagery", which includes a variety of cultural and media depictions of prehistoric life in various manifestations.[1] One attempt to separate these terms has defined paleoartists as artists who "create original skeletal reconstructions and/or restorations of prehistoric animals, or restore fossil flora or invertebrates using acceptable and recognized procedures."[7] Others have pointed out that a definition of paleoart must include a degree of subjectivity, where an artist's style, preferences and opinions come into play along with the goal of accuracy.[8] The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has offered the definition of paleoart as "the scientific or naturalistic rendering of paleontological subject matter pertaining to vertebrate fossils",[9] a definition considered unacceptable by some for its exclusion of non-vertebrate subject matter.[1] Paleoartist Mark Witton defines paleoart in terms of three essential elements: 1) being bound by scientific data, 2) involving biologically-informed restoration to fill in missing data, and 3) relating to extinct organisms. This definition explicitly rules out technical illustrations of fossil specimens from being considered paleoart.[3] This definition, which requires the use of "reasoned extrapolation and informed speculation" to fill in these reconstructive gaps, also explicitly rules out artworks that actively go against known published data. These might be more accurately considered paleontologically-inspired art.[3]

In an attempt to establish a common definition of the term, Ansón & colleagues (2015) conducted an empirical survey of the international paleontological community with a questionnaire on various aspects of paleoart. 78% of the surveyed participants stated agreement with the importance of scientific accuracy in paleoart, although 87% of respondents recognized an increase in accuracy of paleoart over time.[1]

Production

The production of paleoart requires by definition a substantial amount of research and reference-gathering to ensure scientific credibility at the time of production.[3] The artist James Gurney, known for the Dinotopia series of fiction books, has described this interaction between scientists and artists as the artist being the eyes of the scientist, since his illustrations bring shape to the theories; paleoart determines how the public perceives long extinct animals.[10]

Scientific principles

Although every artist's process will differ, Witton (2018) recommends a standard set of requirements to produce artwork that fits the definition. A basic understanding of the subject organism's place in time (geochronology) and space (paleobiogeography) is necessary for restorations of scenes or environments in paleoart. Skeletal reference—not just the bones of vertebrate animals, but including any fossilized structures that support soft tissue, such as lignified plant tissue and coral framework—is crucial for understanding the proportions, size and appearance of extinct organisms. Given that many fossil specimens are known from fragmentary material, an understanding of the organisms' ontogeny, functional morphology, and phylogeny may be required to create scientifically-rigorous paleoart by filling in restorative gaps parsimoniously.[3]

Artistic principles

The success of a piece of paleoart depends on its strength of composition as much as any other genre of artistry. Command of object placement, color, lighting, and shape can be indispensable to communicating a realistic depiction of prehistoric life. Paleoart is unique in its compositional challenge in that its content must be imagined and inferred, as opposed to directly referenced, in many cases, including depictions of animal behavior and environmental topography. To this end, artists must keep in mind the mood and purpose of a composition in creating an effect piece of paleoart.[3]

History

"Proto-paleoart" (pre-1800)

As any cohesive definition of the genre depends on its relationship to scientific knowledge, paleoart can be considered to have originated around the same time as paleontology. However, art of extinct animals has existed long before Henry De la Beche's 1830 painting Duria Antiquior, which is is often credited as the first true paleontological artwork.[4] These older works include sketches, paintings and detailed anatomical restorations, though the relation of these works to observed fossil material is mostly speculative. For example, a Corinthian vase painted sometime between 560 and 540 BCE is thought by some researchers to bear a depiction of an observed fossil skull. This so-called "Monster of Troy", the beast fought by the mythological Greek hero Heracles, somewhat resembles the skull of the giraffid Samotherium.[11] Witton considered that because the painting has significant differences from the skull it is supposedly representing (lack of horns, sharp teeth) the evidence is lacking that it represents "proto-paleoart". Other scholars have suggested that ancient fossils inspired Grecian depictions of griffins, with the mythical chimera of lion and bird anatomy superficially resembling the beak, horns and quadrupedal body plan and fossil of the dinosaur Protoceratops. Similarly, authors have speculated that the huge, unified nasal opening in the skull of fossil mammoths could have inspired ancient artwork and stories of the one-eyed cyclops. However, these ideas have never been substantiated by evidence that isn't more parsimoniously explained by established cultural interpretations of these mythical figures.[3]

The earliest definitive works of "proto-paleoart" that unambiguously depict the life appearance of fossil animals come from fifteenth and sixteenth century Europe. Extinct marine animals were some of the first to be realistically restored as in life.[12] Fifteenth century Flemish painter Petrus Christus was among the first artists known to paint a readily-identifiable image of a fossil, as fossilized shark teeth could be seen hanging on chains in the background of St. Eligius in His Workshop. At the time, these fossils, known as "glossopetrae", were believed to be petrified dragon tongues, and were used as charms for warding away toxins.[13] Another such depiction is Ulrich Vogelsang's statue of a Lindwurm in Klagenfurt, Austria, that dates to 1590. Writings from the time of its creation specifically identify the skull of Coelodonta antiquitatis, the woolly rhinoceros, as the basis for the head in the restoration. This skull had been found in a mine or gravel pit near Klagenfurt in 1335, and remains on display today. Despite its poor resemblance of the skull in question, the Lindwurm statue was thought to be almost certainly inspired by the find.[3]

The German textbook Mundus Subterraneus, authored by scholar Athanasius Kircher in 1678, features a number of illustrations of giant humans and dragons that may have been informed by fossil finds of the day, many of which came from quarries and caves. Some of these may have been the bones of large Pleistocene mammals common to these European caves. Others may have been based on far older fossils of plesiosaurs, which are thought to have informed a unique depiction of a dragon in this book that departs noticeably from the classically slender, serpentine dragon artwork of the era by having a barrel-like body and 'paddle-like' wings. According to some researchers, this dramatic departure from the typical dragon artwork of this time, which is thought to have been informed by the Lindwurm, likely reflects the arrival of a new source of information, such as a speculated discovery of plesiosaur fossils in quarries of the historic Swabia region of Bavaria.[14][3]

Eighteenth century skeletal reconstructions of another mythical creature, the unicorn, are thought to have been inspired by Ice Age mammoth and rhinoceros bones found in a cave near Quedlinburg, Germany, in 1663. These artworks are of uncertain origin and may have been created by Otto von Guericke, the German naturalist who first described the "unicorn" remains in his writings, or Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the author who published the image posthumously in 1749. This rendering represents the oldest known illustration of a fossil skeleton.[3][15]

Early scientific paleoart (1800–1890)

The role of art in disseminating paleontological knowledge took on a new salience with the introduction of the term "dinosaur" by Sir Richard Owen in 1842. With only fragmentary fossil remains known at the time, the question of life appearance of dinosaurs captured the interest of scientist and public alike.[16] With Owen's help, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins created the first life-size sculptures depicting dinosaurs as he thought they may have appeared; he is considered by some to be the first significant artist to apply his skills to the field of dinosaur paleontology.[5] Some of these models were initially created for the Great Exhibition of 1851, but 33 were eventually produced when the Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham, in South London. Owen famously hosted a dinner for 21 prominent men of science inside the hollow concrete Iguanodon on New Year's Eve 1853. However, in 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Gideon Mantell had realised that Iguanodon, of which he was the discoverer, was not a heavy, pachyderm-like animal,[17] as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs; his death left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, and so Owen's vision of dinosaurs became that seen by the public. He had nearly two dozen life-sized sculptures of various prehistoric animals built out of concrete sculpted over a steel and brick framework; two Iguanodon, one standing and one resting on its belly, were included. The dinosaurs remain in place in the park, but their depictions are now outdated in many respects.

"Classic" paleoart (1890–1970)

As the western frontier was further opened up in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the rapidly increasing pace of dinosaur discoveries in the bone-rich badlands of the American Midwest and the Canadian wilderness brought with it a renewed interest in artistic reconstructions of paleontological findings. This 'classic' period saw the emergence of Charles R. Knight, Rudolph Zallinger, and Zdeněk Burian as the three most prominent exponents of paleoart. During this time, dinosaurs were popularly reconstructed as tail-dragging, cold-blooded, sluggish "Great Reptiles" that became a byword for evolutionary failure in the minds of the public.[18]

Charles Knight is generally considered one of the key figures in paleoart during this time. His birth three years after Charles Darwin's publication of the influential Descent of Man, along with the "Bone Wars" between rival American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Marsh raging during his childhood, had poised Knight for rich early experiences in developing an interest in reconstructing prehistoric animals. As an avid wildlife artist who disdained drawing from mounts or photographs, instead preferring to draw from life, Knight grew up drawing living animals, but turned toward prehistoric animals against the backdrop of rapidly-expanding paleontological discoveries and the public energy that accompanied the sensationalist coverage of these discoveries around the turn of the 20th century.[19] Knight's foray into paleoart can be traced to a commission ordered by Dr. Jacob Wortman of a painting of a prehistoric pig, Elotherium, to accompany its fossil display at the American Museum of Natural History. Knight, who had always preferred to draw animals from life, applied his knowledge of modern pig anatomy to the painting, which so thrilled Wortman that the museum then commissioned Knight to paint a series of watercolors of various fossils on display.[20]

Throughout the 1920s, '30s and '40s, Knight went on produce drawings, paintings and murals of dinosaurs, early man, and extinct mammals for the American Museum of Natural History, where he was mentored by Henry Fairfield Osborn, and Chicago's Field Museum, as well as for National Geographic and many other major magazines of the time, culminating in his last major mural for the Everhart Museum of Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1951.[20] Harvard biologist Stephen Jay Gould later remarked on the depth and breadth of influence that Knight's paleoart had on shaping public perception of extinct animals, even without having published original research in the field. Gould, who was a prominent fan and popularizer of Knight's works, used one of Knight's paintings for the cover of his 1991 book Bully for Brontosaurus and another in his 1996 book Dinosaur in a Haystack. Gould described Knight's contribution to scientific understanding in his 1989 book Wonderful Life: "Not since the Lord himself showed his stuff to Ezekiel in the valley of dry bones had anyone shown such grace and skill in the reconstruction of animals from disarticulated skeletons. Charles R. Knight, the most celebrated of artists in the reanimation of fossils, painted all the canonical figures of dinosaurs that fire our fear and imagination to this day".[21] One of Knight's most famous pieces was his Leaping Laelaps, which he produced for the American Museum of Natural History in 1897. This painting was one of the few works of paleoart produced before 1960 to depict dinosaurs as active, fast-moving creatures, heralding the next era of paleontological artworks informed by the Dinosaur Renaissance.[19]

Rudolph Zallinger and Zdeněk Burian both went on to influence the state of dinosaur art while Knight's career began to wind down. Zallinger, who began working for the Yale Peabody Museum illustrating marine algae around the time that the United States entered World War II, began his most iconic piece of paleoart, a five-year mural project for the Yale Peabody Museum, in 1942. This mural, titled The Age of Reptiles, was completed in 1947 and became representative of the modernist consensus of dinosaur biology at that time.[5] He later completed a second great mural for the Peabody, The Age of Mammals, which grew out of a painting published in Life magazine in 1953.[22]

Zdeněk Burian followed the school of Knight and Zallinger, entering modern, biologically-informed paleoart scene via his extensive series of prehistoric life illustrations.[5] Burian entered the world of prehistoric illustration in the early 1930s with illustrations for fictional books set in various prehistoric times by amateur archaeologist Eduard Štorch. These illustrations brought him to the attention of paleontologist Josef Augusta, with whom Burian worked in cooperation from 1935 until Augusta's death in 1968.[23] This collaboration led ultimately to the launching of Burian's career in paleoart.[4]

Some authors have remarked on a darker, more sinister feel to his paleoart than that of his contemporaries, speculating that this style was informed by Burian's experience producing artwork in his native Czechoslovakia during World War II and, afterwards, under Soviet control. His depictions of suffering, death, and the harsh realities of survival that emerged as themes in his paleoart were unique at the time. Original Burian paintings are on exhibit at the Dvůr Králové Zoo, the National Museum (Prague) and at the Anthropos Museum in Brno.[4] In 2017, the first valid Czech dinosaur was named Burianosaurus augustai in honor of both Burian and Josef Augusta.[24]

While Charles Knight, Rudolph Zallinger and Zdeněk Burian dominated the landscape of "classic" scientific paleoart in the first half of the 20th century, they were far from the only paleoartists working at this time. German landscape painter Heinrich Harder was illustrating natural history articles, including a series accompanying articles by science writer Wilhelm Bölsche on earth history for Die Gartenlaube, a weekly magazine, in 1906 and 1908. He also worked with Bölsche to illustrate 60 dinosaur and other prehistoric animal collecting cards for the Reichardt Cocoa Company, titled "Tiere der Urwelt" ("Animals of the Prehistoric World").[4] One of Harder's contemporaries, Danish paleontologist Gerhard Heilmann, produced a large number of sketches and ink drawings related to Archaeopteryx and avian evolution, culminating in his lavishly illustrated and controversial treatise The Origin of Birds, published in 1926.[4]

The Dinosaur Renaissance (1970–2010)

While these artists' style and their artistic mastery of beauty and composition are still lauded today, this classic depiction of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals remained the status quo until the 1960s, when a minor scientific revolution began changing these perceptions following the 1964 discovery of Deinonychus by paleontologist John Ostrom. Ostrom's description of this nearly-complete birdlike dinosaur, published in 1969, challenged the presupposition of dinosaurs as cold-blooded, slow-moving reptiles, and the artistic reconstructions of Deinonychus by his student, Robert Bakker, remain iconic of what came to be known as the Dinosaur Renaissance.[18]

Bakker's influence during this period on then-fledgling paleoartists, such as Gregory S. Paul, as well as on public consciousness brought about a paradigm shift in how dinosaurs were perceived by artist, scientist and layman alike. This influence affected the presentation of museum displays and eventually found its way into popular culture, with the culmination of this period perhaps best marked by the 1990 novel and 1993 film Jurassic Park.[18]

Modern (and post-modern) paleoart (2010–present)

Gregory Paul's high-fidelity archosaur skeletal reconstructions provided a basis for ushering in the modern age of paleoart, which is perhaps best characterized by rigorous, anatomically-conscious work balanced with speculative flair. Novel advances in paleontology, such as new feathered dinosaur discoveries and the various color studies of dinosaur integument that began around 2010, have become representative of paleoart after the turn of the millennium.[25] Alongside and subsequent to Paul, other paleoartists typified this anatomically-rigorous new paleoart outside of archosaurs, including reconstructions of fossil hominids by Jay Matternes and Alfons and Adrie Kennis, as well as of fossil mammals by artists such as Mauricio Antón. Other modern paleoartists of the 'anatomically rigorous' movement include Jason Brougham, Mark Hallett, Scott Hartman, Bob Nicholls, Emily Willoughby and Mark P. Witton.[26][27]

A 2013 study found that older paleoart was still influential in popular culture long after new discoveries made them obsolete. This was explained as cultural inertia.[28] In a 2014 paper, Mark Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway outlined the historical significance of paleoart, and lamented its current state.[29]

Cultural significance

Depictions in popular culture

While the relationship between art and science is built into the various definitions of paleoart, many authors have recognized its distinct cultural importance as well. This includes the endeavor to educate the public about prehistoric life, as well as the economic reality that paleoart's influence on cultural depictions of prehistory in popular media can generate products and merchandise that are globally worth millions of dollars.[29] Paleoart is considered to be invaluable to generating public interest in not only paleontology but in science writ large. Because artistic renditions of prehistoric life directly influence how the public perceives these organisms, the endeavor to create accurate paleoart can be viewed as a unique responsibility of the artist.[30]

Recognition

Since 1999, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has awarded the John J. Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize for achievement in the field. The society says that paleoart "is one of the most important vehicles for communicating discoveries and data among paleontologists, and is critical to promulgating vertebrate paleontology across disciplines and to lay audiences".[9] The SVP is also the site of the occasional/annual "PaleoArt Poster Exhibit", a juried poster show at the opening reception of the annual SVP meetings.

The Museu da Lourinhã organizes the annual International Dinosaur Illustration Contest[31] for promoting the art of dinosaur and other fossils.

Notable, influential paleoartists

Past (pre-dinosaur renaissance) paleoartists

2D artists

- Othenio Abel deceased, active 1910s

- James E. Allen deceased, active 1950s

- Robert T. Bakker active 1960-1990s, led Renaissance

- Henry de la Beche deceased, active 1900s

- Bill Berry deceased, active 1960s

- Zdeněk Burian deceased, active 1960s-1981

- Alexey Petrovich Bystrov

- Amédée Forestier deceased 1930, active 1880s-1920s, notable for his Nebraska Man and Glastonbury Lake Village illustrations

- Konstantin Konstantinovich Flerov

- Joseph M. Gleeson, born 1861, active in late 19th and early 20th centuries

- Heinrich Harder deceased, active 1910s-1920s

- Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins deceased, active 1850s-1870s

- Gerhard Heilmann 1920s, first to restore tail-in-air dinosaurs

- Charles R. Knight 1890s-1940s, biggest influence of early 20th century (i.e. movies)

- Jay Matternes, active 1950s-1970s

- William Diller Matthew deceased, active 1900s-1910s

- Edward Newman deceased, active 1840s

- Othniel Charles Marsh deceased, active 1890s

- John Martin deceased, active 1830s

- George Olshevsky active 1980s

- Richard Owen deceased, active 1850s

- Ernest Untermann deceased, active 1930s

- Ferdinand von Hochstetter deceased, active 1850s-1870s

- Alice B. Woodward deceased, active 1910s

- Rudolph F. Zallinger deceased, active 1950s-1960s

3D artists

- Mikhail Mikhailovich Gerasimov

- Charles Whitney Gilmore

- Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins 1850s-1870s

- Charles R. Knight 1900s-1940s

- Richard Swann Lull 1910s

- Vasily Alekseevich Vatagin

Modern (post-dinosaur renaissance) paleoartists

2D artists

- Marco Ansón 2010s-

- Mauricio Antón 1990s-present, biggest influence in prehistoric mammals

- Andrey Atuchin 2000s-

- Robert T. Bakker 1960s-1990s, led the Renaissance of "active" dinosaurs

- Wayne D. Barlowe 1990s

- Alain Beneteau 2000s-

- Daniel Bensen 2000s-

- John Bindon 1990s-

- Davide Bonadonna 2000s-

- João Boto 2000s-

- Timothy J. Bradley 2000s-

- Kenneth Carpenter active 1980s

- Karen Carr 2000s-

- Zhao Chuang 2000s-

- Cheung Chungtat 2000s-

- John Conway 2000s-

- Julius T. Csotonyi 2000s-

- Ricardo Delgado 1990s

- Danielle Dufault 2000s-

- Alex Ebel 2000s

- Felipe A. Elias 2000s-

- John Gurche 1980s-

- James Gurney 1990s-

- Mohamad Haghani 2010s-

- Scott Hartman 1990s-

- Masato Hattori 2010s-

- Jaime A. Headden 2000s-

- Doug Henderson 1980s-2000s

- Satoshi Kawasaki 2000s-

- Eleanor Kish deceased, active 1970s-1990s

- Joschua Knüppe 2000s-

- Tuomas Koivurinne 1990s-

- Sergey Krasovskiy 2010s-

- Julio Lacerda 2000s-

- Jordan Mallon 2000s-

- Todd Marshall 2000s-

- Raúl Martín 2000s-

- Matthew Martyniuk 2000s-

- John McLoughlin 1970s

- Josef Moravec 1980s-

- Darren Naish 1990s-

- Robert Nicholls (artist) 1990s-

- Vladmir Nikolov 2000s-

- Øyvind M. Padron 2000s-

- William Parsons 1990s-

- Gregory S. Paul 1970s-present, biggest influence of late 20th century-21st century

- Luis Rey 1980s-

- Mineo Shiraishi 1990s-

- John Sibbick 1980s-

- Velizar Simeonovski 2000s-

- Ville Sinkkonen 2000s-

- Michael Skrepnick 1990s-

- Jan Sovak 1980s-

- Frederik Spindler 2000s-

- Christopher Srnka 2000s-

- William Stout 1970s-

- Oda Takashi 1990s-

- Nobu Tamura 2000s-

- Keiji Terakoshi 1980s-

- Peter Trusler 1990s-

- Kayomi Tukimoto 2000s-

- Steve White 1990s-

- Emily Willoughby 2000s-

- Mark P. Witton 2000s-

- Lida Xing 2000s-

3D artists

- Jorge Blanco 1990s-

- Brian Cooley 1980s-

- Elizabeth Daynés 1980s-

- Galileo Hernandez 2000s-

- Alfons and Adrie Kennis 1990s-

- Vlad Konstantinov 2000s-

- David Krentz 2000s-

- Robert Nicholls 1990s-

- Carlos Papolio 1990s-

- David Rankin 2000s-

- Paul Sereno 2000s-

- Gary Staab 1990s-

- Michael Trcic 1990s-

- Mark Witton 2000s-

Gallery

Skeletal restoration of Brontosaurus excelsus, by Othniel Charles Marsh, 1896

Skeletal restoration of Brontosaurus excelsus, by Othniel Charles Marsh, 1896 Eurypterids by Ernst Haeckel, 1914

Eurypterids by Ernst Haeckel, 1914.jpg)

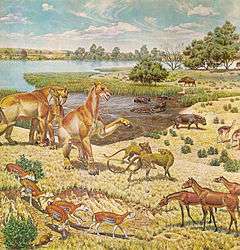

Miocene fauna by Jay Matternes, 1960s

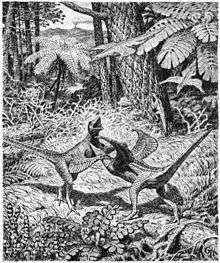

Miocene fauna by Jay Matternes, 1960s- Staurikosaurus and rhynchosaur are animals of Geopark Paleorrota produced by paleoartist Clovis Dapper.

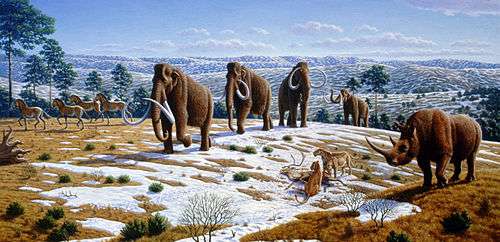

Ice Age fauna by Mauricio Anton, 2008

Ice Age fauna by Mauricio Anton, 2008 Restoration of Anatosuchus by Todd Marshall, 2009

Restoration of Anatosuchus by Todd Marshall, 2009 Quetzalcoatlus models in South Bank, created by Mark P. Witton for the Royal Society's 350th anniversary, 2010

Quetzalcoatlus models in South Bank, created by Mark P. Witton for the Royal Society's 350th anniversary, 2010

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ansón, Marco; Fernández, Manuel H.; Ramos, Pedro A. S. (2015). "Paleoart: term and conditions (A survey among paleontologists)". Current trends in Paleontology and Evolution: 28–34. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- 1 2 Hallett, Mark (1987). "The scientific approach of the art of bringing dinosaurs back to life". In Czerkas, Sylvia J.; Olson, Everett C. Dinosaurs Past and Present (vol 1). Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 97–113. ISBN 978-0938644248.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Witton, Mark P. (2018). The Palaeoartist's Handbook: Recreating prehistoric animals in art. U.K.: Ramsbury: The Crowood Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1785004612.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lescaze, Zoë (2017). Paleoart: Visions of the prehistoric past. Taschen. ISBN 978-3836555111.

- 1 2 3 4 Paul, Gregory S. (2000). "A quick history of dinosaur art". In Paul, Gregory S. The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. New York: Byron Preiss Visual Productions, Inc. pp. 107–112. ISBN 978-0312262266.

- ↑ Hone, Dave (3 September 2012). "Drawing dinosaurs: how is palaeoart produced?". The Guardian.

- ↑ Debus, Allen A.; Debus, Diane E. (2002). "Paleoimagery: The Evolution of Dinosaurs in Art. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co. ISBN 978-0786464203.

- ↑ Witton, Mark P. Recreating an Age of Reptiles. Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1785003349.

- 1 2 "Society of Vertebrate Paleontology: Lanzendorf-National Geographic Paleoart Prize". Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ Gurney, James (2009). Imaginative Realism: How to Paint What Doesn't Exist. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-0740785504.

- ↑ Mayor, Adrienne (2011). The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times (second edition). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691150133.

- ↑ Davidson, Jane P. (2015). "Misunderstood marine reptiles: Late nineteenth-century artistic reconstructions of prehistoric marine life". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 118 (1–2): 53–67. doi:10.1660/062.118.0107.

- ↑ Davidson, Jane P. (2008). A History of Paleontology Illustration. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253351753.

- ↑ Abel, Othenio (1939). Vorzeitliche Tierreste im Deutschen Mthus, Brachtum und Volksglauben. Jena (Gustav Fischer).

- ↑ Ariew, R (1998). "Leibniz on the unicorn and various other curiosities". Early Science and Medicine (3): 39–50.

- ↑ Colagrande, John; Felder, Larry (2000). In the Presence of Dinosaurs. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. pp. 168–177. ISBN 978-0737000894.

- ↑ Mantell, Gideon A. (1851). Petrifications and their teachings: or, a handbook to the gallery of organic remains of the British Museum. London: H. G. Bohn. OCLC 8415138.

- 1 2 3 White, Steve (2012). Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-0857685841.

- 1 2 Milner, Richard (2012). Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-0810984790.

- 1 2 Stout, William (2005). Introduction. Charles R. Knight: Autobiography of an Artist. By Knight, Charles Robert. G.T. Labs. pp. ix–xiii. ISBN 978-0-9660106-8-8.

- ↑ "Welcome to the World of Charles R. Knight".

- ↑ "Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History: Rudolph Franz Zallinger". Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ↑ Hochmanová-Burianová, Eva (1991). Zdeněk Burian - pravěk a dobrodružství (rodinné vzpomínky). Prague: Magnet-Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 80-85434-28-8.

- ↑ Madzia, Daniel; Boyd, Clint A.; Mazuch, Martin (2017). "A basal ornithopod dinosaur from the Cenomanian of the Czech Republic". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology: 1–13. doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1371258.

- ↑ Terakado, Kazuo (2017). The Art of the Dinosaur: Illustrations by the Top Paleoartists in the World. PIE International. ISBN 978-4756249227.

- ↑ Conway, John; Kosemen, C.M.; Naish, Darren (2012). All Yesterdays. London: Irregular Books. ISBN 978-1291177121.

- ↑ White, Steve (2017). Dinosaur Art II: The Cutting Edge of Paleoart. Titan Books. ISBN 978-1785653988.

- ↑ Ross, Robert M.; Duggan-Haas, Don; Allmon, Warren D. (2013). "The posture of Tyrannosaurus rex: Why do student views lag behind the science?" (pdf). Journal of Geoscience Education. 61: 145–160. Bibcode:2013JGeEd..61..145R. doi:10.5408/11-259.1. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- 1 2 Witton, Mark P.; Naish, Darren; Conway, John (2014). "State of the palaeoart" (pdf). Palaeontologia Electronica. 17 (3): 5E. doi:10.26879/145. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ Witton, Mark; Daynès, Elisabeth; Willoughby, Emily; Ugueto, Gabriel; Staab, Gary; Hall, Jenn (August 2018), "Art imitating ancient life", The Biologist, London: The Royal Society of Biology, 65 (4), pp. 10–15

- ↑ International Dinosaur Illustration Contest Archived 2009-02-06 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleoart. |

- Paleoartists at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Paleoartists Hall of Fame