Olsztyn

| Olsztyn | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

|

Motto(s): Olsztyn – Miasto Młode Duchem… (Olsztyn – a city young in spirit…) | |||

Olsztyn  Olsztyn | |||

| Coordinates: 53°47′N 20°30′E / 53.783°N 20.500°E | |||

| Country | Poland | ||

| Voivodeship | Warmian-Masurian | ||

| County | city county | ||

| Established | 14th century | ||

| Town rights | 1353 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Piotr Grzymowicz | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 88.328 km2 (34.104 sq mi) | ||

| Highest elevation | 154 m (505 ft) | ||

| Lowest elevation | 88 m (289 ft) | ||

| Population (2017) | |||

| • City | 173,070 | ||

| • Density | 1,965,3/km2 (50,900/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 270,000 | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| Postal code | 10-001 to 11–041 | ||

| Area code(s) | +48 89 | ||

| Car plates | NO | ||

| Climate | Dfb | ||

| Website | http://www.olsztyn.eu | ||

Olsztyn ([ˈɔlʂtɨn] (![]()

![]()

Founded as Allenstein in the 14th century, Olsztyn was under the control and influence of the Teutonic Order until 1466, when it was incorporated into the Polish Crown.[1] For centuries the city was an important centre of trade, crafts, science and administration in the Warmia region linking Warsaw with Königsberg.[2] Following the First Partition of Poland in 1772 Warmia was annexed by Prussia and ceased to be the property of the clergy. In the 19th century the city changed its status completely, becoming the most prominent economic hub of the southern part of Eastern Prussia. The construction of a railway and early industrialization greatly contributed to Olsztyn's significance. Following World War II, the city returned to Poland in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement.

Since 1999 Olsztyn has been the capital city of the Warmia-Masuria. In the same year, the University of Warmia and Masuria was founded from the fusion of three other local universities. Today, the Castle of Warmian Bishops houses a museum and is a venue for concerts, art exhibitions, film shows and other cultural events, which make Olsztyn a popular tourist destination.[3][4]

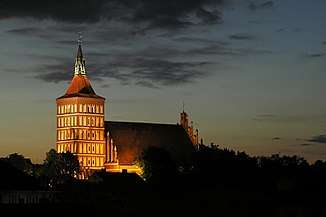

The most important sights of the city include the medieval Old Town and the Olsztyn Cathedral, which dates back more than 600 years. The picturesque market square is part of the European Route of Brick Gothic and the cathedral is regarded as one of the greatest monuments of Gothic architecture in Poland.[5]

Olsztyn, for a number of years, has been ranked very highly in quality of life, income, employment and safety. It currently is one of the best places in Poland to live and work.[6][7] It is also one of the happiest cities in the country.[7]

History

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In 1346, the forest was cleared at a location on the Alle River (now Łyna River) for a new settlement in Prussian Warmia (former German Ermland). The following year, Teutonic Knights began the construction of an Ordensburg castle as a stronghold against the Old Prussians.[8] The German name "Allenstein" refers to a stronghold on the Alle River – which became known in Polish transliteration as Olsztyn. Allenstein received municipal rights in October 1353,[9] and the castle was completed in 1397.[10] The town was captured by the Kingdom of Poland during the Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War in 1410, and again in 1414 during the Hunger War, but it was returned to the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights after hostilities ended.

Allenstein joined the Prussian Confederation in 1440 and rebelled against the Teutonic Knights in 1454 upon the outbreak of the Thirteen Years' War. Although the Teutonic Knights recaptured the town the following year, it was retaken by Polish troops in 1463. The Second Peace of Thorn in 1466 designated Allenstein and the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia as part of Royal Prussia under the sovereignty of the Polish Crown.[11]

From 1516 to 1521, Nicolaus Copernicus lived at the castle as administrator of both Olsztyn and Melzak (now Pieniężno). Copernicus was in charge of the Polish defense of Olsztyn during the Polish-Teutonic War of 1519–21.[12]

Olsztyn was sacked by Swedish troops in both 1655 and 1708 during the Polish-Swedish wars, and the town's population was nearly wiped out in 1710 by epidemics of bubonic plague and cholera.

The town became part of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1772 after the First Partition of Poland. Poles became subject to extensive Germanisation policies. A Prussian census recorded a population of 1,770 people, predominantly farmers, and Allenstein was administered within the newly created Province of East Prussia. It was visited by Napoleon Bonaparte[13] in 1807 after his victories over the Prussian Army at Jena and Auerstedt. By 1825, the town was inhabited by 1341 Germans and 1266 Poles.[14] The first German-language newspaper, the Allensteiner Zeitung, began publishing in 1841. The town hospital was founded in 1867.

In 1871, with the unification of Germany under Prussian hegemony, Allenstein became part of the German Empire. Two years later, the city was connected by railway to Toruń. Its first Polish language newspaper, the Gazeta Olsztyńska, was founded in 1886. Allenstein's infrastructure developed[15] rapidly: gas was installed in 1890, telephones in 1892, public water supply in 1898, and electricity in 1907. In 1905, the city became the capital of Regierungsbezirk Allenstein, a government administrative region in East Prussia. From 1818 to 1910, the city was administered within the East Prussia Allenstein District, after which it became an independent city.

_-_16.04.1917.jpg)

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Russian troops captured Allenstein, but it was recovered by the Imperial German Army in the Battle of Tannenberg. The battle took place closer to Allenstein than to Tannenberg (now Stębark), but the Germans, recalling their defeat in the 1410 Battle of Grunwald (German: Battle of Tannenberg), named it "Tannenberg II" for nationalistic reasons.

After the defeat of Germany in World War I, the East Prussian plebiscite was held in 1920 to determine whether the populace of the region, including Allenstein, wished to remain in German East Prussia or become part of Poland. In order to advertise the plebiscite, special postage stamps were produced by overprinting German stamps and sold on 3 April of that year. One kind of overprint read PLÉBISCITE / OLSZTYN / ALLENSTEIN, while the other read TRAITÉ / DE / VERSAILLES / ART. 94 et 95 inside an oval whose border gave the full name of the plebiscite commission. Each overprint was applied to 14 denominations ranging from 5 Pfennigs to 3 Marks. The plebiscite was held on 11 July, and produced 362,209 votes (97.8%) for Germany and 7,980 votes (2.2%) for Poland.

The football club SV Hindenburg Allenstein played in Allenstein from 1921 to 1945. After the January 1933 Nazi seizure of power in Germany, Jews in Allenstein were increasingly persecuted. Also anti-Polish sentiment became more visible. The Gazeta Olsztyńska was abolished by the German authorities, the newspaper's headquarters was demolished and the editor-in-chief Seweryn Pieniężny was arrested and executed in the Hohenbruch German concentration camp. In 1935, the German Wehrmacht made the city the seat of the Allenstein Militärische Bereich. It was then home of the 11th and 217th infantry divisions and 11th Artillery Regiment.

On 12 October 1939, after the German invasion of Poland that began World War II, the Wehrmacht established an Area Headquarters for a military district that controlled the environs of Allenstein, including Lötzen (now Giżycko), and Ciechanów in occupied Poland. Beginning in 1939, members of the Polish-speaking minority, especially members of the Union of Poles in Germany, were persecuted or deported back to Poland.

On 22 January 1945, near the end of the war, Allenstein was plundered and burned by the conquering Soviet Red Army, and much of its German population fled.[16] On 2 August 1945, the city became part of Poland under border changes promulgated at the Potsdam Conference, and officially became the Polish "Olsztyn". In October 1945, the remnants of the German population were forcibly expelled.[17]

A tire factory was founded in Olsztyn in 1967. Its subsequent names included OZOS, Stomil and Michelin.[18]

In 1989 the former Gazeta Olsztyńska headquarters was rebuilt and re-opened as a museum.

Olsztyn became the capital of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship in 1999. It was previously in the Olsztyn Voivodeship.

Olsztyn Castle

The castle was built between 1346–1353 and by then it had one wing on the north-east side of the rectangular courtyard. Access to the castle lead from the drawbridge over the river Łyna (Alle), surrounded by a belt of defensive walls and a moat. The south-west wing of the castle was built in the 15th century, the tower situated in the west corner of the courtyard, from the middle of the 14th century, was rebuilt in the early 16th century and had a round shape on a square base and was 40 meters high. At the same time the castle walls were raised to a height of 12 meters and a second belt of the lower walls was built. The castle walls were partly combined with city walls, which made the castle look like it had been a powerful bastion defending access to the city. The castle was owned by Warmia Chapter, which until 1454, together with the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia, was under military protection of the Teutonic Knights and their Monastic State of Prussia.

The castle had played a huge role in the Polish-Teutonic wars by then. After the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, the Poles took it after a few days siege. In the Thirteen Years' War (1454–66) it was jumping from rule to rule. The Knights threatened the castle and the town in 1521, but the defence was very effective. They contained one failed assault. There is a connection between the history of the castle, the city of Olsztyn, and Nicolaus Copernicus. He prepared the defense of Olsztyn against the invasion of the Teutonic Knights.

In the sixteenth century, there were two prince-bishops of Warmia that stayed there: Johannes Dantiscus – "the first sarmatian poet, endowed with the imperial laurel wreath for "Latin Songs" (1538, 1541) and Marcin Kromer, who wrote with equal ease in Latin and Polish scientific and literary works (1580). Kromer consecrated the chapel of St. Anna, which was built in the south-west wing of the castle. In the course of time both wings of the castle lost military importance, which for residential purposes has become very convenient. In 1779 Prince-Bishop Ignacy Krasicki stopped here as well.

After the Royal Prussian annexation of Warmia in 1772, the castle became the property of the state board of estates (War and Domain Chamber, Kriegs- und Domänenkammer). In 1845 the bridge over the moat was replaced by a dam better connecting the castle with the city. In 1901–1911 a general renovation of the castle was performed, however several sections of the building were violated at the same time where they changed the original look of the castle e.g. putting on window frames in a cloister. The tower was crowned in 1921 and again in 1926 in the halls of the castle, became a museum.

In 1945 the whole castle became home to the Masurian Museum, which today is called the Museum of Warmia and Masuria. In addition there are also popular events held within the frameworks of the Olsztyn Artistic Summer and so called "evenings of the castle" and "Sundays in the Museum".

Jewish community

Though Jews did trade in the city fairs during medieval times, they were not allowed to trade freely in the villages surrounding the city.[19] In 1718, Bishop Teodor Andrzej Potocki imposed a ban on Jewish trade.[20] Other bishops after him continued the ban, which apparently wasn't successful since the city population complained about Jews dealing with animal leather and other products in 1742. Permanent Jews were found in the city in 1780, and they were allowed to settle outside the city walls.[21] In 1814, the Simonson brothers opened the first Jewish store in town. In 1850, the city official authority announced that any citizen that hosted a wandering Jew in his house, would be fined and imprisoned.[22]

The Jewish community of the city as a congregation was established in 1820. Shortly after, a prayer room was established on Richterstrasse. In 1877, the congregation bought a plot of land on Liebstädterstrasse and built a synagogue there.[23] A Jewish cemetery was built on Seestrasse (present-day Grundwalzka). While at its peak, the town's Jewish population was 448 Jews in 1933.

On Kristallnacht, the town synagogue was destroyed and later used as a bomb shelter.[24] Now, a sports club sits on the site of the synagogue.[25]

By 1939, 135 Jews were left in the city, after most others fled from the country. Those who lived in town in 1940 were deported to Nazi concentration camps.[26] In June 1946, 16 Holocaust survivors settled in the city and in 1948, the congregation had 190 worshipers. Most of them emigrated to Israel throughout the next few decades. There is no current trace of the Jewish cemetery.[27]

The city was the birthplace of world-famous Jewish architect Erich Mendelsohn. In town, Mendelsohn planned the mourners' chapel (called the Mendelsohn house) next to the cemetery.[28] The building is currently restored.[29] In addition, it was the birthplace of German Socialist and SPD leader Hugo Haase. Frieda Strohmberg, an Impressionist, lived and worked in the city from 1910 to 1927. Documentation of the Jewish owned shops in town exists.[30]

Geography

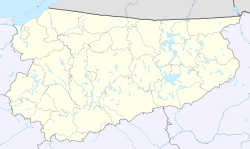

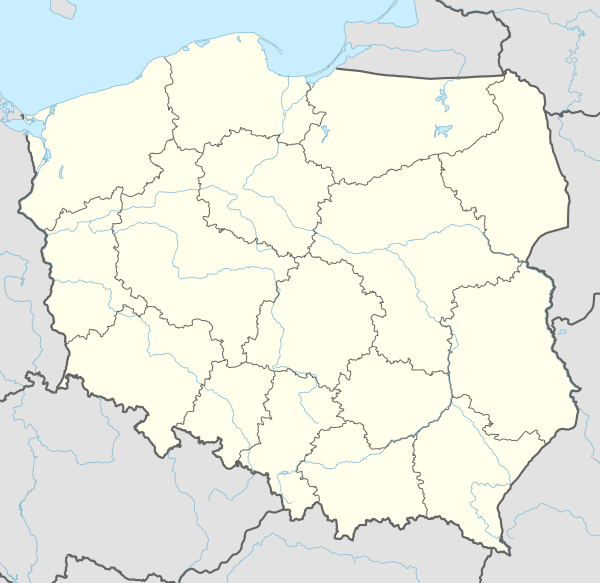

Olsztyn is located in the north-east part of Poland in the region known as the "Thousand Lakes".

Greenbelt

More than half of the forests occupying 21.2% of the city area form a single complex of the Municipal Forest (1050 ha) used mainly for recreation and tourism purposes. Within the Municipal Forest area are situated two peat-land flora sanctuaries, Mszar and Redykajny. Municipal greenery (560 ha, 6.5% of the town area) developed in the form of numerous parks, green spots and three cemeteries over a century-old. The greenery includes 910 monuments of nature and groups of protected trees in the form of beech, oak, maple and lime-lined avenues.

Lakes

The city is situated in a lake region of forests and plains. There are 15 lakes inside the administrative bounds of the city (13 with areas greater than 1 ha). The overall area of lakes in Olsztyn is about 725 ha, which constitutes 8.25% of the total city area.

| Lake | Area (ha) | Maximum depth (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Lake Ukiel (a.k.a. Jezioro Krzywe) | 412 | 43 |

| Lake Kortowskie | 89.7 | 17.2 |

| Lake Track (a.k.a. Trackie) | 52.8 | 4.6 |

| Lake Skanda | 51.5 | 12 |

| Lake Redykajny | 29.9 | 20.6 |

| Lake Długie | 26.8 | 17.2 |

| Lake Sukiel | 20.8 | 25 |

| Lake Tyrsko | 18.6 | 30.6 |

| Lake Stary Dwór | 6.0 | 23.3 |

| Lake Siginek | 6.0 | insufficient data |

| Lake Czarne | approximately 1.3 | insufficient data |

| Lake Żbik | approximately 1.2 | insufficient data |

| Lake Pereszkowo | approximately 1.2 | insufficient data |

| Lake Mummel | approximately 0.3 | insufficient data |

| Lake Modrzewiowe | 0.25 | insufficient data |

Demographics

Olsztyn's population includes 3280 Germans and 1283 Ukrainians.

Administrative division

Olsztyn is divided into 23 districts:

| District | Population | Area | Density |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brzeziny | 1,456 | 2.25 km2 (0.87 sq mi) | 647.1/km² |

| Dajtki (German: Deuthen) | 5,863 | 7.5 km2 (2.9 sq mi) | 781.7/km² |

| Generałów | 6,500 | no data | no data |

| Grunwaldzkie | 6,027 | 1.46 km2 (0.56 sq mi) | 4,128.1/km² |

| Gutkowo (German: Göttkendorf) | 2,256 | 7.2 km2 (2.8 sq mi) | 313.3/km² |

| Jaroty | 29,046 | 4.82 km2 (1.86 sq mi) | 6,026.1/km² |

| Kętrzyńskiego | 7,621 | 4.83 km2 (1.86 sq mi) | 1,577.8/km² |

| Kormoran | 16,166 | 1.1 km2 (0.4 sq mi) | 14,696.4/km² |

| Kortowo (German: Kortau) | 1,131 | 4.22 km2 (1.63 sq mi) | 268/km² |

| Kościuszki | 6,704 | 1.18 km2 (0.46 sq mi) | 5,681.4/km² |

| Likusy (German: Likusen) | 2,286 | 2.1 km2 (0.8 sq mi) | 1,088.6/km² |

| Mazurskie | 4,615 | 5.98 km2 (2.31 sq mi) | 771.7/km² |

| Nad Jeziorem Długim | 2,408 | 4.23 km2 (2 sq mi) | 569.3/km² |

| Nagórki (German: Bergenthal) | 12,538 | 1.69 km2 (0.65 sq mi) | 7,418.9/km² |

| Pieczewo (German: Stolzenberg) | 10,918 | 2.24 km2 (0.86 sq mi) | 4,874.1/km² |

| Podgrodzie | 11,080 | 1.35 km2 (0.52 sq mi) | 8,207.4/km² |

| Podleśna | 10,414 | 9.93 km2 (3.83 sq mi) | 1,048.7/km² |

| Pojezierze | 13,001 | 2.39 km2 (0.92 sq mi) | 5,439.7/km² |

| Redykajny (German: Redigkainen) | 1,555 | 6.1 km2 (2.36 sq mi) | 254.9/km² |

| Śródmieście | 3,448 | 0.58 km2 (0.22 sq mi) | 5,944.8/km² |

| Wojska Polskiego | 6,759 | 5.03 km2 (2 sq mi) | 1,343.7/km² |

| Zatorze | 6,988 | 0.45 km2 (0.17 sq mi) | 15,528.9/km² |

| Zielona Górka | 1,015 | 6.44 km2 (2.49 sq mi) | 157.6/km² |

There are many smaller districts: Jakubowo (German: Jakobsberg), Karolin, Kolonia Jaroty, Kortowo II, Łupstych (German: Abstich), Niedźwiedź (German: Bärenbruch), Piękna Góra, Podlesie, Pozorty (German: Posorten), Skarbówka Poszmanówka, Słoneczny Stok, Stare Kieźliny, Stare Miasto, Stare Zalbki, Stary Dwór (German: Althof), Track. These do not have council representative assemblies.

Culture

Theatres

- Stefan Jaracz Theatre (est. 1925) the host of International Theatre Festival DEMOLUDY

- Puppet Theatre

Cinemas

- Helios

- Multikino

Museums

- Museum of Warmia and Mazury (Muzeum Warmii i Mazur) – Olsztyn's largest museum.

- Gazeta Olsztyńska House (Dom „Gazety Olsztyńskiej”)

- Museum of Nature (Muzeum Przyrody)

- Museum of Sports (Muzeum Sportu)

- Muzeum Nowoczesności

Architecture

- The Old Town

- The Gothic castle of the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia built during the 14th century.

- St. James's Cathedral (Polish: św. Jakuba, German: St. Jacob or St. Jakob).

- Old Town Hall on the Market Square – built in the mid-14th century.

- Gazeta Olsztyńska House at Fish Market.

- The town walls and the Upper Gate (since the mid-19th century known as the High Gate).

- Neogothic church of the Holy Heart of Jesus, built during the years 1901–1902

- The New City Hall

- The Railway Bridge over the River Łyna gorge near Artyleryjska and Wyzwolenia streets, built during the years 1872–1873

- The Jerusalem Chapel, built in 1565

- Church of St. Lawrence, built during the late 14th century

- FM- and TV-mast Olsztyn-Pieczewo – 360 metres high, since the collapse of the Warsaw radio mast the tallest structure in Poland

Music

Death metal act Vader, regarded as one of the first Death metal bands from Poland.

Economy

The Michelin tyre company (former Stomil Olsztyn) is the largest employer in the region of Warmia and Masuria.[31] Other important industries are food processing and furniture manufacturing.

Transport

There is a bus network with 33 bus lines, including 6 suburban lines and 2 night-time lines. An 11 kilometres (7 miles) tram network was built 2011–2015; 15 Tramino cars were ordered from Solaris in September 2012. Olsztyn has train connections to Warsaw, Gdańsk, Szczecin, Poznań, Bydgoszcz, Iława, Działdowo and Ełk.

Education

Sports

- Indykpol AZS Olsztyn – men's volleyball team playing in the Polish Volleyball League (PLS, Polska Liga Siatkówki)

- OKS Stomil Olsztyn – men's football team, (8 seasons in the Polish Ekstraklasa as Stomil Olsztyn)

- Warmia Traveland Olsztyn – men's handball team playing in the Seria A (Polish First League)

- AZS UWM Trójeczka Olsztyn – men's basketball team playing in the Polish Second League

- WMPD Olsztyn – men's rugby team, playing in the First Polish League

- Budowlani Olsztyn – a wrestling team

- Joanna Jedrzejczyk – UFC women's Strawweight Champion

- Olsztyn Lakers – American football team

Politics

Members of the Sejm elected from Olsztyn constituency in 2005:

- Mieczysław Aszkiełowicz, Self-Defense of the Republic of Poland (Samoobrona Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej)

- Beata Bublewicz, Civic Platform (PO, Platforma Obywatelska)

- Jerzy Gosiewski, Law and Justice (PiS, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość)

- Tadeusz Iwiński, Democratic Left Alliance (SLD, Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej)

- Edward Ośko, League of Polish Families (LPR, Liga Polskich Rodzin)

- Adam Puza, Law and Justice (PiS, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość)

- Sławomir Rybicki, Civic Platform (PO, Platforma Obywatelska)

- Lidia Staroń, Civic Platform (PO, Platforma Obywatelska)

- Aleksander Marek Szczygło, Law and Justice (PiS, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość)

- Zbigniew Włodkowski, Polish Peasant Party (PSL, Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe)

Members of Senate elected from Olsztyn constituency in 2005:

- Ryszard Józef Górecki, Civic Platform (PO, Platforma Obywatelska)

- Jerzy Szmit, Law and Justice (PiS, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość)

Notable residents

- Johannes von Leysen (1310–1388), town founder and mayor

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), astronomer, administrator, and town commander

- Johannes Knolleisen (+1511), German academic and provider of academic stipends

- Lucas David (1503–1583), German historian of Prussia

- Marcin Kromer (1512–1589), Polish cartographer, diplomat and historian, personal secretary of Kings of Poland, Bishop of Warmia

- Hugo Haase (1863–1919), Jewish-German politician, jurist and pacifist

- Franz Justus Rarkowski (1873–1950), military bishop (1938–45)

- August Trunz (1875–1963), founder of the Prussica-Sammlung Trunz

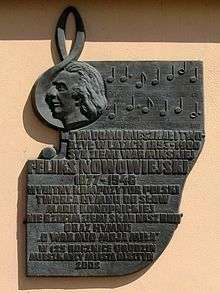

- Feliks Nowowiejski (1877–1946), Polish composer, conductor, concert organist

- Maximilian Kaller (1880–1947) German prelate, bishop of Ermland in 1930–45

- Erich Mendelsohn (1887–1953), German-Jewish architect who fled the Nazis

- Olga Desmond (1891–1964), German dancer and actress

- Günter Wand (1912–2002), German conductor

- Kurt Baluses (1914–72) German football (soccer) player and manager

- Hans-Jürgen Wischnewski (1922–2005), German politician

- Curt Lowens (1925–2017), German actor

- Leonhard Pohl (1929–2014), German gymnast

- Józef Glemp (1929–2013), Polish prelate, bishop of Warmia 1979–81

- Jörg Kuebart (1934–2018) German general of the German Air Force

- Karl-Heinz Hopp (1936–2007) German rower who competed in the 1960 Summer Olympics

- Wolf Lepenies (born 1941), German sociologist, political scientist and author

- Eugeniusz Geno Malkowski (born 1942), Polish artist, painter and academic

- Ulrich Schrade (1943–2009), German-Polish philosopher and pedagogue

- Marian Bublewicz (1950–1993), Polish rally and race driver of the 80s and 90s

- Juliusz Machulski (born 1955), Polish film director

- Izabela Trojanowska (born 1955), Polish actress and singer

- Andrzej Friszke (born 1956), Polish historian

- Krzysztof Hołowczyc (born 1962), Polish rally driver

- Piotr "Peter" Wiwczarek (born 1965), Polish guitarist and vocalist

- Mamed Khalidov (born 1980), Russian-Polish mixed martial artist

- Wojciech Grzyb (born 1981), Polish volleyball player

- Julia Marcell (born 1982), Polish singer/songwriter and pianist

- Małgorzata Jasińska (born 1984), Polish professional cyclist (retd.)

- Adrian Mierzejewski (born 1986), Polish footballer

- Joanna Jędrzejczyk (born 1987), Muay-Thai and MMA fighter, former UFC Women's Strawweight Champion.

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Olsztyn is twinned with:

|

|

|

Olsztyn belongs to the Federation of Copernicus Cities, an association of cities where Copernicus lived and worked, such as Bologna, Frombork, Kraków, and Toruń. The main office of the federation is situated at Olsztyn Planetarium and Astronomical Observatory, located on St. Andrew's Hill (143 m) in a former water tower erected in 1897.

Notes

- ↑ "Olsztyn History". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Local history – Information about the town – Olsztyn – Virtual Shtetl". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ o.o., StayPoland Sp. z. "Olsztyn – Tourism – Tourist Information – Olsztyn, Poland -". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Presentation of castle and museum trail, cultural – historical attractions of the Baltic Sea region". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Budziłło, Elzbieta. "Olsztyn – Copernicus city with 15 lakes". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "W Olsztynie żyje się (prawie) najlepiej. W rankingu miast awansowaliśmy na czwarte miejsce". Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Ranking jakości miejskiego życia. W Olsztynie żyje się bardzo dobrze". Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ "Miasto Olsztyn – perła Warmii, największe miasto województwa warmińsko-mazurskiego". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Zabytki Olsztyn Atrakcje Historii Zwiedzanie Miasta w Centrum". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Historia". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Historia Olsztyna". Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ Höhne, Manfred. "Historia Olsztyna – Prusy Wschodnie". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Historia Olsztyna – Castles of Poland". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Historia Pomorza: (1815–1850), Gerard Labuda, Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk, page 157, 1993

- ↑ "Olsztyn – Gołębnik w środku miasta. Atrakcje turystyczne Olsztyna. Ciekawe miejsca Olsztyna". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Olsztyn – Barwna historia miasta – Zabawa.Mazury.pl". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ joanna. "Historia lokalna – Olsztyn rok 1945 i pierwsze lata powojenne". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ e.V., Christoph Pienkoss, DV – Deutscher Verband für Städtebau und Wohnungswesen. "EuRoB – Europäische Route der Backsteingotik – Strona internetowa – Miasta nad Szlaku – Polska – Olsztyn – Historia miasta". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ W. Knercer, Cmentarze i zabytki kultury żydowskiej w województwie olsztyńskim, "Borussia", no. 6, 1993, p. 53; vide K. Forstreuter, Die ersten Juden in Ostpreussen, "Altpreussische Forschungen", ch. 14, 1937, pp. 42–48.

- ↑ "History – Jewish community before 1989 – Olsztyn – Virtual Shtetl". Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ J. Jasiński, Olsztyn w latach 1772 – 1918, in: Olsztyn "1353 – 2003, ed. S. Achremczyk, W. Ogrodziński, Olsztyn 2003, p. 228.

- ↑ J. Jasiński, Olsztyn w latach 1772 – 1918, in: Olsztyn 1353 – 2003, ed. S. Achremczyk, W. Ogrodziński, Olsztyn 2003, p. 229.

- ↑ "Old synagogue – Synagogues, prayer houses and others – Heritage Sites – Olsztyn – Virtual Shtetl". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Archive – east-prussia – Allenstein". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Jewish culture in Olsztyn – Virtual Shtetl". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ https://www.bundesarchiv.de/gedenkbuch/directory.html#frmResults (matches for "Allenstein", with marked: "Wohnort" and "Geburtsort"; (as of 25 March 2009); http://www.yadvashem.org/wps/portal/!ut/p/_s.7_0_A/7_0_2KE?next_form=advanced_search (people living in Olsztyn before the war – matches for "Allenstein", with marked: "Before the War", (as of 25 March 2009); http://www.yadvashem.org/wps/portal/!ut/p/_s.7_0_A/7_0_2KE?next_form=advanced_search (people born in Olsztyn – matches for "Allenstein", with marked: "Birth"; (as of 25 March 2009).

- ↑ "Jewish Cemetery (Zyndrama z Maszkowic Street) – Cemeteries – Heritage Sites – Olsztyn – Virtual Shtetl". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Family House of Erich Mendelsohn – 21 Podgórna Street (Oberstrasse, today's 10 Staromiejska) – Heritage sites – Heritage Sites – Olsztyn – Virtual Shtetl". Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Mendelsohn's house will be renovated – Virtual Shtetl". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "History – Jewish community before 1989 – Olsztyn – Virtual Shtetl". Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "100-milionowa opona w olsztyńskiej fabryce Michelin – Autoflesz.pl – Niezależny Portal Motoryzacyjny". Autoflesz.pl. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ "Le service municipal des jumelages" [Châteauroux municipal twinning service]. Ville de Châteauroux (in French). Archived from the original on 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2013-08-04.

- ↑ "List of Twin Towns in the Ruhr District" (PDF). 2009 Twins2010.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Bielsko-Biała – Partner Cities". 2008 Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

References

- http://www.olsztyn.eu/ (in Polish)

- http://www.bezrobocie.net/stat_powiaty.php/ (in Polish)

- http://www.zamkigotyckie.org.pl/olsztyn.htm (in Polish)

- http://www.pascal.pl/atrakcja.php?id=25797 (in Polish)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olsztyn. |

.jpg)