Old English literature

| Part of a series on |

| Old English |

|---|

|

Dialects |

| History of literature by era |

|---|

| Bronze Age |

| Classical |

| Early Medieval |

| Medieval |

| Early Modern |

| Modern by century |

|

|

Old English literature or Anglo-Saxon literature, encompasses literature written in Old English, in Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066. "Cædmon's Hymn", composed in the 7th century, according to Bede, is often considered the oldest extant poem in English, whereas the later poem, The Grave is one of the final poems written in Old English, and presents a transitional text between Old and Middle English.[1] The Peterborough Chronicle can also be considered a late-period text, continuing into the 12th century.

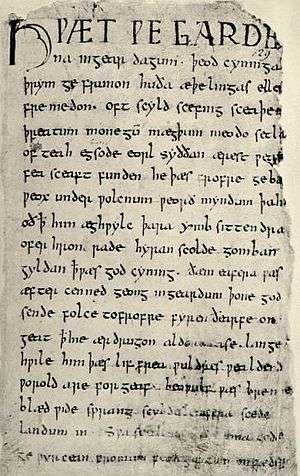

The poem Beowulf, which often begins the traditional canon of English literature, is the most famous work of Old English literature. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has also proven significant for historical study, preserving a chronology of early English history.

In descending order of quantity, Old English literature consists of: sermons and saints' lives; biblical translations; translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers; Anglo-Saxon chronicles and narrative history works; laws, wills and other legal works; practical works on grammar, medicine, geography; and poetry.[2] In all there are over 400 surviving manuscripts from the period, of which about 189 are considered "major".[3]

Besides Old English literature, Anglo-Saxons wrote a number of Anglo-Latin works.

Scholarship

Old English literature has gone through different periods of research; in the 19th and early 20th centuries the focus was on the Germanic and pagan roots that scholars thought they could detect in Old English literature.[4] Later, on account of the work of Bernard F. Huppé,[5] the influence of Augustinian exegesis was emphasised.[6] Today, along with a focus upon paleography and the physical manuscripts themselves more generally, scholars debate such issues as dating, place of origin, authorship, and the connections between Anglo-Saxon culture and the rest of Europe in the Middle Ages, and literary merits.

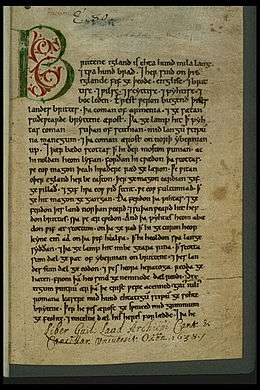

Extant manuscripts

A large number of manuscripts remain from the Anglo-Saxon period, with most written during its last 300 years (9th to 11th centuries).

Manuscripts written in both Latin and the vernacular remain. It is believed that Irish missionaries are responsible for the scripts used in early Anglo-Saxon texts, which include the Insular half-uncial (important Latin texts) and Insular minuscule (both Latin and the vernacular). In the 10th century, the Caroline minuscule was adopted for Latin, however the Insular minuscule continued to be used for Old English texts. Thereafter, it was increasingly influenced by Caroline minuscule, while retaining certain distinctively Insular letter-forms.[7]

There were considerable losses of manuscripts as a result of the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century.[2] Scholarly study of the language began when the manuscripts were collected by scholars and antiquarians such as Matthew Parker, Laurence Nowell and Sir Robert Bruce Cotton.[8]

Old English manuscripts have been highly prized by collectors since the 16th century, both for their historic value and for their aesthetic beauty with their uniformly spaced letters and decorative elements.[2]

There are four major poetic manuscripts:

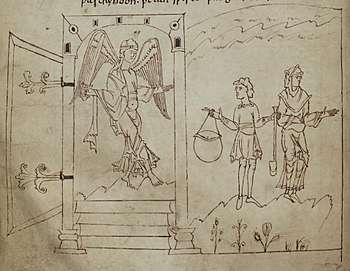

- The Junius manuscript, also known as the Cædmon manuscript, is an illustrated collection of poems on biblical narratives.

- The Exeter Book is an anthology, located in the Exeter Cathedral since it was donated there in the 11th century.

- The Vercelli Book contains both poetry and prose; it is not known how it came to be in Vercelli.

- The Beowulf Manuscript (British Library Cotton Vitellius A. xv), sometimes called the Nowell Codex, contains prose and poetry, typically dealing with monstrous themes, including Beowulf.[9]

Seven major scriptoria produced a good deal of Old English manuscripts: Winchester; Exeter; Worcester; Abingdon; Durham; and two Canterbury houses, Christ Church and St. Augustine's Abbey.[10] In addition, some Old English text survives on stone structures and other ornate objects.[2]

Regional dialects include: Northumbrian; Mercian; Kentish; and West dialect, leading to the speculation that much of the poetry may have been translated into West Saxon at a later date.[11] An example of the dominance of the West Saxon dialect is a pair of charters, from the Stowe and British Museum collections, which outline grants of land in Kent and Mercia, but are nonetheless written in the West Saxon dialect of the period. [12]

Early English manuscripts often contain later annotations in the margins of the texts; it is a rarity to find a completely unannotated manuscript. These include corrections, alterations and expansions of the main text, as well as commentary upon it, and even unrelated texts.[13][14] The majority of these annotations appear to date to the 13th century and later.[15]

Poetry

Old English poetry falls broadly into two styles or fields of reference, the heroic Germanic and the Christian. Almost all Old English poets are anonymous.

Although there are Anglo-Saxon discourses on Latin prosody, the rules of Old English verse are understood only through modern analysis of the extant texts. The first widely accepted theory was constructed by Eduard Sievers (1893), who distinguished five distinct alliterative patterns.[16] His system of alliterative verse is based on accent, alliteration, the quantity of vowels, and patterns of syllabic accentuation. It consists of five permutations on a base verse scheme; any one of the five types can be used in any verse. The system was inherited from and exists in one form or another in all of the older Germanic languages. Two poetic figures commonly found in Old English poetry are the kenning, an often formulaic phrase that describes one thing in terms of another (e.g. in Beowulf, the sea is called the whale road) and litotes, a dramatic understatement employed by the author for ironic effect.[16] Alternative theories have been proposed, such as the theory of John C. Pope (1942), which uses musical notation to track the verse patterns.[17] J. R. R. Tolkien describes and illustrates many of the features of Old English poetry in his 1940 essay "On Translating Beowulf".[18]

Even though all extant Old English poetry is written and literate, it is assumed that Old English poetry was an oral craft that was performed by a scop and accompanied by a harp.

Composition

Named poets

Most Old English poems are recorded without authors, and very few names are known with any certainty; the primary three are Cædmon, Aldhelm, and Cynewulf.[19]

Cædmon is considered the first Old English poet whose work still survives. According to the account in Bede's Historia ecclesiastica, he was first a herdsman before living as a monk at the abbey of Whitby in Northumbria in the 7th century.[19][20] Only his first poem, comprising nine-lines, Cædmon's Hymn, remains, in Northumbrian, West-Saxon and Latin versions that appear in 19 surviving manuscripts:[21]

| Modern English[22] | West Saxon[23] | Northumbrian[22] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now we must praise the Guardian of heaven, The power and conception of the Lord, And all His works, as He, eternal Lord, Father of glory, started every wonder. First He created heaven as a roof, The holy Maker, for the sons of men. Then the eternal Keeper of mankind Furnished the earth below, the land, for men, Almighty God and everlasting Lord. |

|

|

Cynewulf has proven to be a difficult figure to identify, but recent research suggests he was an Anglian poet from the early part of the 9th century. Four poems are attributed to him, signed with a runic acrostic at the end of each poem; these are The Fates of the Apostles and Elene (both found in the Vercelli Book), and Christ II and Juliana (both found in the Exeter Book).[24]

Although William of Malmesbury claims that Aldhelm, bishop of Sherborne (d. 709), performed secular songs while accompanied by a harp, none of these Old English poems survives.[24] Paul G. Remely has recently proposed that the Old English Exodus may have been the work of Aldhelm, or someone closely associated with him.[25]

Bede is often thought to be the poet of a five-line poem entitled Bede's Death Song, on account of its appearance in a letter on his death by Cuthbert. This poem exists in a Northumbrian and later version.[26]

Alfred is said to be the author of some of the metrical prefaces to the Old English translations of Gregory's Pastoral Care and Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy. Alfred is also thought to be the author of 50 metrical psalms, but whether the poems were written by him, under his direction or patronage, or as a general part in his reform efforts is unknown.[27]

Oral tradition

The hypotheses of Milman Parry and Albert Lord on the Homeric Question came to be applied (by Parry and Lord, but also by Francis Magoun) to verse written in Old English. That is, the theory proposes that certain features of at least some of the poetry may be explained by positing oral-formulaic composition. While Anglo-Saxon (Old English) epic poetry may bear some resemblance to Ancient Greek epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey, the question of if and how Anglo-Saxon poetry was passed down through an oral tradition remains a subject of debate, and the question for any particular poem unlikely to be answered with perfect certainty.

Parry and Lord had already demonstrated the density of metrical formulas in Ancient Greek, and observed that the same phenomenon was apparent in the Old English alliterative line:

- Hroþgar maþelode helm Scildinga ("Hrothgar spoke, protector of the Scildings")

- Beoƿulf maþelode bearn Ecgþeoƿes ("Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow")

In addition to verbal formulas, many themes have been shown to appear among the various works of Anglo-Saxon literature. The theory proposes to explain this fact by suggesting that the poetry was composed of formulae and themes from a stock common to the poetic profession, as well as literary passages composed by individual artists in a more modern sense. Larry Benson introduced the concept of "written-formulaic" to describe the status of some Anglo-Saxon poetry which, while demonstrably written, contains evidence of oral influences, including heavy reliance on formulas and themes.[28] Frequent oral-formulaic themes in Old English poetry include "Beasts of Battle"[29] and the "Cliff of Death".[30] The former, for example, is characterised by the mention of ravens, eagles, and wolves preceding particularly violent depictions of battle. Among the most thoroughly documented themes is "The Hero on the Beach". D. K. Crowne[31] first proposed this theme, defined by four characteristics:

- A Hero on the Beach.

- Accompanying "Retainers".

- A Flashing Light.

- The Completion or Initiation of a Journey.

One example Crowne cites in his article is that which concludes Beowulf's fight with the monsters during his swimming match with Breca:

| Modern English | West Saxon | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Those sinful creatures had no fill of rejoicing that they consumed me, assembled at feast at the sea bottom; rather, in the morning, wounded by blades they lay up on the shore, put to sleep by swords, so that never after did they hinder sailors in their course on the sea. The light came from the east, the bright beacon of God. |

|

Crowne drew on examples of the theme's appearance in twelve Anglo-Saxon texts, including one occurrence in Beowulf. It was also observed in other works of Germanic origin, Middle English poetry, and even an Icelandic prose saga. John Richardson held that the schema was so general as to apply to virtually any character at some point in the narrative, and thought it an instance of the "threshold" feature of Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey monomyth. J.A. Dane, in an article[32] (characterised by Foley as "polemics without rigour"[33]) claimed that the appearance of the theme in Ancient Greek poetry, a tradition without known connection to the Germanic, invalidated the notion of "an autonomous theme in the baggage of an oral poet." Foley's response was that Dane misunderstood the nature of oral tradition, and that in fact the appearance of the theme in other cultures showed that it was a traditional form.[34]

Genres and themes

Heroic poetry

The Old English poetry which has received the most attention deals with the Germanic heroic past. The longest at 3,182 lines, and the most important, is Beowulf, which appears in the damaged Nowell Codex. Beowulf relates the exploits of the hero Beowulf, King of the Weder-Geats or Angles, around the middle of the 5th century. The author is unknown, and no mention of Britain occurs. Scholars are divided over the date of the present text, with hypotheses ranging from the 8th to the 11th centuries.[35][36] It has achieved much acclaim as well as sustained academic and artistic interest.[37]

Other heroic poems besides Beowulf exist. Two have survived in fragments: The Fight at Finnsburh, controversially interpreted by many to be a retelling of one of the battle scenes in Beowulf, and Waldere, a version of the events of the life of Walter of Aquitaine. Two other poems mention heroic figures: Widsith is believed to be very old in parts, dating back to events in the 4th century concerning Eormanric and the Goths, and contains a catalogue of names and places associated with valiant deeds. Deor is a lyric, in the style of Consolation of Philosophy, applying examples of famous heroes, including Weland and Eormanric, to the narrator's own case.[24]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contains various heroic poems inserted throughout. The earliest from 937 is called The Battle of Brunanburh, which celebrates the victory of King Athelstan over the Scots and Norse. There are five shorter poems: capture of the Five Boroughs (942); coronation of King Edgar (973); death of King Edgar (975); death of Alfred the son of King Æthelred (1036); and death of King Edward the Confessor (1065).[24]

The 325 line poem The Battle of Maldon celebrates Earl Byrhtnoth and his men who fell in battle against the Vikings in 991. It is considered one of the finest, but both the beginning and end are missing and the only manuscript was destroyed in a fire in 1731.[38] A well-known speech is near the end of the poem:

| Modern English | West Saxon[39] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thought shall be the harder, the heart the keener, courage the greater, as our strength lessens. Here lies our leader in the dust, all cut down; always may he mourn who now thinks to turn away from this warplay. I am old, I will not go away, but I plan to lie down by the side of my lord, by the man so dearly loved. |

|

Old English heroic poetry was handed down orally from generation to generation. As Christianity began to appear, re-tellers often recast the tales of Christianity into the older heroic stories.

Elegiac poetry

Related to the heroic tales are a number of short poems from the Exeter Book which have come to be described as "elegies"[40] or "wisdom poetry".[41][42] They are lyrical and Boethian in their description of the up and down fortunes of life. Gloomy in mood is The Ruin, which tells of the decay of a once glorious city of Roman Britain (cities in Britain fell into decline after the Romans departed in the early 5th century, as the early English continued to live their rural life), and The Wanderer, in which an older man talks about an attack that happened in his youth, where his close friends and kin were all killed; memories of the slaughter have remained with him all his life. He questions the wisdom of the impetuous decision to engage a possibly superior fighting force: the wise man engages in warfare to preserve civil society, and must not rush into battle but seek out allies when the odds may be against him. This poet finds little glory in bravery for bravery's sake. The Seafarer is the story of a somber exile from home on the sea, from which the only hope of redemption is the joy of heaven. Other wisdom poems include Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wife's Lament, and The Husband's Message. Alfred the Great wrote a wisdom poem over the course of his reign based loosely on the neoplatonic philosophy of Boethius called the Lays of Boethius.[43]

Classical and Latin poetry

Several Old English poems are adaptations of late classical philosophical texts. The longest is a 10th-century translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy contained in the Cotton manuscript Otho A.vi.[44] Another is The Phoenix in the Exeter Book, an allegorisation of the De ave phoenice by Lactantius.[45]

Other short poems derive from the Latin bestiary tradition. Some examples include The Panther, The Whale and The Partridge.[45]

Riddles

Anglo-Saxon riddles are part of Anglo-Saxon literature. The most famous Anglo-Saxon riddles are found in the Exeter Book. This book contains secular and religious poems and other writings, along with a collection of 94 riddles, although there is speculation that there may have been closer to 100 riddles in the book. The riddles are written in a similar manner, but "it is unlikely that the whole collection was written by one person."[46] It is more likely that many scribes worked on this collection of riddles. Although the Exeter Book has a unique and extensive collection of Anglo-Saxon riddles,[47] riddles were not uncommon during this era. Riddles were both comical and obscene.[46]

Christian poetry

Saints' lives

The Vercelli Book and Exeter Book contain four long narrative poems of saints' lives, or hagiography. In Vercelli are Andreas and Elene and in Exeter are Guthlac and Juliana.

Andreas is 1,722 lines long and is the closest of the surviving Old English poems to Beowulf in style and tone. It is the story of Saint Andrew and his journey to rescue Saint Matthew from the Mermedonians. Elene is the story of Saint Helena (mother of Constantine) and her discovery of the True Cross. The cult of the True Cross was popular in Anglo-Saxon England and this poem was instrumental in promoting it.[48]

Guthlac consists of two poems about the English 7th century Saint Guthlac. Juliana describes the life of Saint Juliana, including a discussion with the devil during her imprisonment.[48]

Biblical paraphrases

There are a number of partial Old English Bible translations and paraphrases surviving. The Junius manuscript contains three paraphrases of Old Testament texts. These were re-wordings of Biblical passages in Old English, not exact translations, but paraphrasing, sometimes into beautiful poetry in its own right. The first and longest is of Genesis (originally presented as one work in the Junius manuscript but now thought to consist of two separate poems, A and B), the second is of Exodus and the third is Daniel. Contained in Daniel are two lyrics, Song of the Three Children and Song of Azarias, the latter also appearing in the Exeter Book after Guthlac.[49] The fourth and last poem, Christ and Satan, which is contained in the second part of the Junius manuscript, does not paraphrase any particular biblical book, but retells a number of episodes from both the Old and New Testament.[50]

The Nowell Codex contains a Biblical poetic paraphrase, which appears right after Beowulf, called Judith, a retelling of the story of Judith. This is not to be confused with Ælfric's homily Judith, which retells the same Biblical story in alliterative prose.[45]

Old English translations of Psalms 51-150 have been preserved, following a prose version of the first 50 Psalms.[45] There are verse translations of the Gloria in Excelsis, the Lord's Prayer, and the Apostles' Creed, as well as some hymns and proverbs.[43]

Original Christian poems

In addition to Biblical paraphrases are a number of original religious poems, mostly lyrical (non-narrative).[45]

The Exeter Book contains a series of poems entitled Christ, sectioned into Christ I, Christ II and Christ III.[45]

Considered one of the most beautiful of all Old English poems is Dream of the Rood, contained in the Vercelli Book.[45] The presence of a portion of the poem (in Northumbrian dialect[51]) carved in ruins on an 8th century stone cross found in Ruthwell, Dumfriesshire, verifies the age of at least this portion of the poem. The Dream of the Rood is a dream vision in which the personified cross tells the story of the crucifixion. Christ appears as a young hero-king, confidant of victory, while the cross itself feels all the physical pain of the crucifixion, as well as the pain of being forced to kill the young lord.[52]

| Modern English[53] | West Saxon[53] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full many a dire experience on that hill. I saw the God of hosts stretched grimly out. Darkness covered the Ruler's corpse with clouds, A shadow passed across his shining beauty, under the dark sky. All creation wept, bewailed the King's death. Christ was on the cross. |

|

The dreamer resolves to trust in the cross, and the dream ends with a vision of heaven.

There are a number of religious debate poems. The longest is Christ and Satan in the Junius manuscript, it deals with the conflict between Christ and Satan during the forty days in the desert. Another debate poem is Solomon and Saturn, surviving in a number of textual fragments, Saturn is portrayed as a magician debating with the wise king Solomon.[45]

Other poems

Other poetic forms exist in Old English including short verses, gnomes, and mnemonic poems for remembering long lists of names.[43]

There are short verses found in the margins of manuscripts which offer practical advice, such as remedies against the loss of cattle or how to deal with a delayed birth, often grouped as charms. The longest is called Nine Herbs Charm and is probably of pagan origin. Other similar short verses, or charms, include For a Swarm of Bees, Against a Dwarf, Against a Stabbing Pain, and Against a Wen.[43]

There are a group of mnemonic poems designed to help memorise lists and sequences of names and to keep objects in order. These poems are named Menologium, The Fates of the Apostles, The Rune Poem, The Seasons for Fasting, and the Instructions for Christians.[43]

Features

Simile and metaphor

Anglo-Saxon poetry is marked by the comparative rarity of similes. This is a particular feature of Anglo-Saxon verse style, and is a consequence both of its structure and of the rapidity with which images are deployed, to be unable to effectively support the expanded simile. As an example of this, Beowulf contains at best five similes, and these are of the short variety. This can be contrasted sharply with the strong and extensive dependence that Anglo-Saxon poetry has upon metaphor, particularly that afforded by the use of kennings. The most prominent example of this in The Wanderer is the reference to battle as a "storm of spears".[54] This reference to battle shows how Anglo-Saxons viewed battle: as unpredictable, chaotic, violent, and perhaps even a function of nature.

Alliteration

Old English poetry traditionally alliterates, meaning that a sound (usually the initial consonant sound) is repeated throughout a line. For instance, in the first line of Beowulf, "Hwaet! We Gar-Dena | in gear-dagum",[55] (meaning "Lo! We ... of the Spear Danes in days of yore"), the stressed words Gar-Dena and gear-dagum alliterate on the consonant "G".

Variation

The Old English poet was particularly fond of describing the same person or object with varied phrases, (often appositives) that indicated different qualities of that person or object. For instance, the Beowulf poet refers in three and a half lines to a Danish king as "lord of the Danes" (referring to the people in general), "king of the Scyldings" (the name of the specific Danish tribe), "giver of rings" (one of the king's functions is to distribute treasure), and "famous chief". Such variation, which the modern reader (who likes verbal precision) is not used to, is frequently a difficulty in producing a readable translation.[56]

Caesura

Old English poetry, like other Old Germanic alliterative verse, is also commonly marked by the caesura or pause. In addition to setting pace for the line, the caesura also grouped each line into two couplets.

Prose

The amount of surviving Old English prose is much greater than the amount of poetry.[43] Of the surviving prose, the majority consists of the homilies, saints' lives and biblical translations from Latin.[2] The division of early medieval written prose works into categories of "Christian" and "secular", as below, is for convenience's sake only, for literacy in Anglo-Saxon England was largely the province of monks, nuns, and ecclesiastics (or of those laypeople to whom they had taught the skills of reading and writing Latin and/or Old English). Old English prose first appears in the 9th century, and continues to be recorded through the 12th century as the last generation of scribes, trained as boys in the standardised West Saxon before the Conquest, died as old men.[43]

Christian prose

The most widely known secular author of Old English was King Alfred the Great (849–899), who translated several books, many of them religious, from Latin into Old English. Alfred, wanting to restore English culture, lamented the poor state of Latin education:

So general was [educational] decay in England there were very few on this side of the Humber who could...translate a letter from Latin into English; and I believe that there were not many beyond the Humber

Alfred proposed that students be educated in Old English, and those who excelled should go on to learn Latin. Alfred's cultural program produced the following translations: Gregory the Great's The Pastoral Care, a manual for priests on how to conduct their duties; The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius; and The Soliloquies of Saint Augustine.[58] In the process, some original content was interweaved through the translations.[59]

Other important[58] Old English translations include: Historiae adversum paganos by Orosius, a companion piece for St. Augustine's The City of God; the Dialogues of Gregory the Great; and Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People.[60]

Ælfric of Eynsham, who wrote in the late 10th and early 11th century, is believed to have been a pupil of Æthelwold.[43] He was the greatest and most prolific writer of Anglo-Saxon sermons,[58] which were copied and adapted for use well into the 13th century.[61] In the translation of the first six books of the Bible (Old English Hexateuch), portions have been assigned to Ælfric on stylistic grounds. He included some lives of the saints in the Catholic Homilies, as well as a cycle of saints' lives to be used in sermons. Ælfric also wrote an Old English work on time-reckoning, and pastoral letters.[61]

In the same category as Ælfric, and a contemporary, was Wulfstan II, archbishop of York. His sermons were highly stylistic. His best known work is Sermo Lupi ad Anglos in which he blames the sins of the English for the Viking invasions. He wrote a number of clerical legal texts Institutes of Polity and Canons of Edgar.[62]

One of the earliest Old English texts in prose is the Martyrology, information about saints and martyrs according to their anniversaries and feasts in the church calendar. It has survived in six fragments. It is believed to date from the 9th century by an anonymous Mercian author.[58]

The oldest collections of church sermons is the Blickling homilies, found in a 10th-century manuscript.[58]

There are a number of saint's lives prose works; beyond those written by Ælfric are the prose life of Saint Guthlac (Vercelli Book), the life of Saint Margaret and the life of Saint Chad. There are four additional lives in the earliest manuscript of the Lives of Saints, the Julius manuscript: Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, Saint Mary of Egypt, Saint Eustace and Saint Euphrosyne.[61]

There are six major manuscripts of the Wessex Gospels, dating from the 11th and 12th centuries. The most popular, Old English Gospel of Nicodemus, is treated in one manuscript as though it were a 5th gospel; other apocryphal gospels in translation include the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, Vindicta salvatoris, Vision of Saint Paul and the Apocalypse of Thomas.[61]

Secular prose

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was probably started in the time of King Alfred the Great and continued for over 300 years as a historical record of Anglo-Saxon history.[58]

A single example of a Classical romance has survived: a fragment of the story of Apollonius of Tyre was translated in the 11th century from the Gesta Romanorum.[61][63]

A monk who was writing in Old English at the same time as Ælfric and Wulfstan was Byrhtferth of Ramsey, whose book Handboc was a study of mathematics and rhetoric. He also produced a work entitled Computus, which outlined the practical application of arithmetic to the calculation of calendar days and movable feasts, as well as tide tables.[58]

Ælfric wrote two proto-scientific works, Hexameron and Interrogationes Sigewulfi, dealing with the stories of Creation. He also wrote a grammar and glossary in Old English called Latin, later used by students interested in learning Old French because it had been glossed in Old French.[61]

In the Nowell Codex is the text of The Wonders of the East which includes a remarkable map of the world, and other illustrations. Also contained in Nowell is Alexander's Letter to Aristotle. Because this is the same manuscript that contains Beowulf, some scholars speculate it may have been a collection of materials on exotic places and creatures.[64]

There are a number of interesting medical works. There is a translation of Apuleius's Herbarium with striking illustrations, found together with Medicina de Quadrupedibus. A second collection of texts is Bald's Leechbook, a 10th-century book containing herbal and even some surgical cures. A third collection, known as the Lacnunga, includes many charms and incantations.[8]

Anglo-Saxon legal texts are a large and important part of the overall corpus. By the 12th century they had been arranged into two large collections (see Textus Roffensis). They include laws of the kings, beginning with those of Aethelbert of Kent and ending with those of Cnut, and texts dealing with specific cases and places in the country. An interesting example is Gerefa which outlines the duties of a reeve on a large manor estate. There is also a large volume of legal documents related to religious houses. These include many kinds of texts: records of donations by nobles; wills; documents of emancipation; lists of books and relics; court cases; guild rules. All of these texts provide valuable insights into the social history of Anglo-Saxon times, but are also of literary value. For example, some of the court case narratives are interesting for their use of rhetoric.[8]

Reception

Old English literature did not disappear in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. Many sermons and works continued to be read and used in part or whole up through the 14th century, and were further catalogued and organised. During the Reformation, when monastic libraries were dispersed, the manuscripts were collected by antiquarians and scholars. These included Laurence Nowell, Matthew Parker, Robert Bruce Cotton and Humfrey Wanley. In the 17th century there began a tradition of Old English literature dictionaries and references. The first was William Somner's Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum (1659). Lexicographer Joseph Bosworth began a dictionary in the 19th century which was completed by Thomas Northcote Toller in 1898 called An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, which was updated by Alistair Campbell in 1972.[65]

Because Old English was one of the first vernacular languages to be written down, nineteenth-century scholars searching for the roots of European "national culture" (see Romantic Nationalism) took special interest in studying Anglo-Saxon literature, and Old English became a regular part of university curriculum. Since WWII there has been increasing interest in the manuscripts themselves—Neil Ker, a paleographer, published the groundbreaking Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon in 1957, and by 1980 nearly all Anglo-Saxon manuscript texts were in print. J.R.R. Tolkien is credited with creating a movement to look at Old English as a subject of literary theory in his seminal lecture Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics (1936).[66]

Old English literature has had some influence on modern literature, and notable poets have translated and incorporated Old English poetry. Well-known early translations include Alfred, Lord Tennyson's translation of The Battle of Brunanburh William Morris's translation of Beowulf and Ezra Pound's translation of The Seafarer. The influence of the poetry can be seen in modern poets T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and W. H. Auden. Tolkien adapted the subject matter and terminology of heroic poetry for works like The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and John Gardner wrote Grendel, which tells the story of Beowulf's opponent from his own perspective.[66]

More recently other notable poets such as Paul Muldoon, Seamus Heaney, Denise Levertov and U. A. Fanthorpe have all shown an interest in Old English poetry. In 1987 Denise Levertov published a translation of Cædmon's Hymn under her title "Caedmon" in the collection Breathing the Water. This was then followed by Seamus Heaney's version of the poem "Whitby-sur-Moyola" in his The Spirit Level (1996) Paul Muldoon's "Caedmona's Hymn" in his Moy Sand and Gravel (2002) and U. A. Fanthorpe's "Caedmon's Song" in her Queuing for the Sun (2003). These translations differ greatly from one another, just as Seamus Heaney's Beowulf (1999) deviates from earlier, similar projects. Heaney uses Irish diction across Beowulf to bring what he calls a "special body and force" to the poem, foregrounding his own Ulster heritage, "in order to render (the poem) ever more 'willable forward/again and again and again.'"

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lerer 1997.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cameron 1982, p. 275.

- ↑ Ker 1990, p. xv.

- ↑ Stanely 1975.

- ↑ Huppé 1959.

- ↑ Hill 2002.

- ↑ Baker 2003, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Cameron 1982, p. 286.

- ↑ Sisam 1962, p. 96.

- ↑ Cameron 1982, p. 276.

- ↑ Baker 2003, p. 10.

- ↑ Sweet 1908, p. 54.

- ↑ Teeuwen 2016, p. 221.

- ↑ Powell 2009, p. 151.

- ↑ Parkes 2007, p. 19.

- 1 2 Sievers 1893.

- ↑ Pope 1942.

- ↑ Tolkien 1983.

- 1 2 Cameron 1982, p. 277.

- ↑ Vernon 1861, p. 145.

- ↑ O'Donnell 2005, p. 78.

- 1 2 Hamer, Richard Frederick Sanger (2015). A choice of Anglo-Saxon verse. London: Faber & Faber Ltd. p. 126. ISBN 9780571325399. OCLC 979493193. Taken from A.H. Smith, Three Northumbrian Poems, 1933, in turn taken from the manuscript known as the Moore Bede (Cambridge Library MS. kk.5.16).

- ↑ Sweet, Henry (1943). An Anglo-Saxon Reader (13th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 43. Taken from the Corpus MS. at Oxford (279), commonly referred to as the "O" manuscript of Bede's Ecclesiastical History.

- 1 2 3 4 Cameron 1982, p. 278.

- ↑ Remley 2005.

- ↑ Smith 1978.

- ↑ Treschow, Gill & Swartz 2009.

- ↑ Foley 1985, p. 42; Foley cites Benson (1966).

- ↑ Magoun 1953.

- ↑ Fry 1987.

- ↑ Crowne, D.K. (1960). "THE HERO ON THE BEACH: An Example of Composition by Theme in Anglo-Saxon Poetry". Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. 61 (4): 362–372.

- ↑ Dane 1982.

- ↑ Foley 1985, p. 200.

- ↑ Foley 1985.

- ↑ S. Downey (February 2015), "Review of The Dating of Beowulf: A Reassessment", Choice Reviews Online, 52 (6), doi:10.5860/CHOICE.187152

- ↑ Neidorf, Leonard, ed. (2014), The Dating of Beowulf: A Reassessment, Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, ISBN 978-1-84384-387-0

- ↑ Bjork and Niles, Robert and John (1998). A Beowulf Handbook (1st ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. p. IX. ISBN 0803261500.

- ↑ Cameron 1982, p. 278-279.

- ↑ Hamer, Richard Frederick Sanger (2015). A choice of Anglo-Saxon verse. London: Faber & Faber Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 9780571325399. OCLC 979493193. Lists a number of sources: E.D. Laborde (1936), E.V. Gordon (1937), D.G. Scragg (1981), Bernard J. Muir (1989), J.C. Pope & R.D. Fulk (2001), J.R.R. Tolkien (1953), N.F. Blake (1965), O.D. Macrae-Gibson (1970), Donald Scragg (1991), Jane Cooper (1993).

- ↑ Drabble 1990.

- ↑ Cameron 1982, p. 280-281.

- ↑ Woodring 1995, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cameron 1982, p. 281.

- ↑ Sedgefield 1899.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cameron 1982, p. 280.

- 1 2 Black 2009.

- ↑ Lind 2007.

- 1 2 Cameron 1982, p. 279.

- ↑ Cameron 1982, p. 279-280.

- ↑ Wrenn 1967, p. 97, 101.

- ↑ Sweet 1908, p. 154.

- ↑ Baker 2003, p. 201.

- 1 2 Hamer, Richard Frederick Sanger (2015). A choice of Anglo-Saxon verse. London: Faber & Faber Ltd. pp. 166–169. ISBN 9780571325399. OCLC 979493193. Lists a number of sources: B. Dickins & A.S.C. Ross (1934), M. Swanton (1970), J.C. Pope & R.D. Fulk (2001), R. Woolf (1958), J.A. Burrow (1959).

- ↑ The Wanderer line 99

- ↑ Alexander 1995, line 1.

- ↑ Howe 2012.

- ↑ Baswell, Christopher; Schotter, Anne Howland, eds. (2006). The Longman Anthology of British Literature:Third Edition. Volume 1A: The Middle Ages. New York: Longman. p. 130. ISBN 0321067622. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cameron 1982, p. 284.

- ↑ Vernon 1861, p. 129.

- ↑ On the Old English translation of Bede's Ecclesiastical History, see Rowley (2011a) and Rowley (2011b)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cameron 1982, p. 285.

- ↑ Cameron 1982, p. 284-285.

- ↑ Vernon 1861, p. 121.

- ↑ Cameron 1982, p. 285-286.

- ↑ Cameron 1982, p. 286-287.

- 1 2 Cameron 1982, p. 287.

References

- Alexander, Michael, ed. (1995), Beowulf: A Glossed Text, Penguin .

- Baker, Peter S. (2003), Introduction to Old English, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0631234543, OCLC 315514208

- Benson, Larry D. (1966), "The Literary Character of Anglo-Saxon Formulaic Poetry", Publications of the Modern Language Association, 81 (5): 334–41, doi:10.2307/460821 .

- Black, Joseph, ed. (2009), The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, 1: The Medieval Period (2nd ed.), Broadview Press .

- Bosworth, Joseph; Toller, Thomas Northcote (1889), An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary .

- Campbell, Alistair (1972), Enlarged Addenda and Corrigenda to the Supplement of An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary Based on the Manuscript Collections of Joseph Bosworth, ISBN 978-0198631101 .

- Cameron, Angus (1982), "Anglo-Saxon Literature", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, pp. 274–288, ISBN 0-684-16760-3 .

- Dane, Joseph A., "Finnsburh and Iliad IX: A Greek Survival of the Medieval Germanic Oral-Formulaic Theme The Hero on the Beach", Neophilologus, 66 (3): 443–449 .

- Drabble, Margaret (ed.), "Elegies", The Oxford Companion to English Literature (5th ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-866130-4 .

- Foley, John M. (1985), Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography, Garland .

- Fry, Donald K. (1987), "The Cliff of Death in Old English Poetry", in Foley, John Miles, Comparative Research in Oral Traditions: A Memorial for Milman Parry, Slavica, pp. 213–34 .

- Hill, Joyce (2002), "Confronting 'Germania Latina': changing responses to Old English biblical verse", in Liuzza, R.M., The poems of MS Junius 11: basic readings, pp. 1–19 .

- Howe, Nicholas (2012), "Scullionspeak: Rev. of Heaney, Beowulf", in Schulman, Jana K.; Szarmach, Paul, Beowulf at Kalamazoo: Essays on Translation and Performance, Studies in Medieval Culture, 50, Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, pp. 347–58, ISBN 9781580441520 .

- Huppé, Bernard F. (1959), Doctrine and Poetry: Augustine's Influence on Old English Poetry, SUNY Press .

- Ker, Neil R. (1990), Catalogue of Manuscripts containing Anglo-Saxon (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press .

- Lind, Carol (2007). Riddling the voices of others: The Old English Exeter Book riddles and a pedagogy of the anonymous (Ph.D.). Illinois State University.

- Magoun, Francis P. (1953), "The Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry", Speculum, 28: 446–67 .

- O'Donnell, Daniel Paul (2005), Cædmon's Hymn: A Multi-Media Study, Edition and Archive, D.S. Brewer .

- Lerer, Seth (1997), "Genre of the Grave and the Origins of the Middle English Lyric", Modern Language Quarterly, 58: 127–61 .

- Parkes, M.B. (2007-01-01), "Raedan, areccan, smeagan: How the Anglo-Saxons read", Anglo-Saxon England / 26, Cambridge Univ. Press, ISBN 9780521038515, OCLC 263427328

- Pope, John C. (1942), The Rhythm of Beowulf: an interpretation of the normal and hypermetric verse-forms in Old English poetry, Yale University Press .

- Powell, K. (2009-01-01), "Viking invasions and marginal annotations in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 162", Anglo-Saxon England / 37, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521767361, OCLC 444440054

- Remely, Paul G. (2005), "Aldhelm as Old English Poet: Exodus, Asser, and the Dicta Ælfredi", in Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe; Andy Orchard, Latin Learning and English Lore: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature for Michael Lapidge, University of Toronto Press, pp. 90–108 .

- Rowley, Sharon M. (2011a), The Old English version of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica, Boydell & Brewer

- Rowley, Sharon (2011b), "'Ic Beda'...'Cwæð Beda': Reinscribing Bede in the Old English Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum", in Carruthers, Leo; Chai-Elsholz, Raeleen; Silec, Tatjana, Palimpsests and the Literary Imagination of Medieval England, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 95–113 .

- Sedgefield, Walter John, ed. (1899), King Alfred's Old English Version of Boethius: De consolatione philosophiae (published 1968) .

- Sievers, Eduard (1893), Altgermanische Metrik, Halle .

- Smith, A.H., ed. (1978), Three Northumbrian Poems, University of Exeter Press .

- Stanely, E.G. (1975), Imagining the Anglo-Saxon Past: The Search for Anglo-Saxon Paganism and Anglo-Saxon Trial by Jury, Boydell & Brewer (published 2000) .

- Sweet, Henry (1908), An Anglo-Saxon Reader (8th ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Teeuwen, M. (2016-01-01), "Three annotated letter manuscripts: scholarly practices of religious Franks in the margin unveiled", Religious Franks. Religion and power in the Frankish Kingdoms. Studies in honour of Mayke de Jong., Manchester University Press, ISBN 9780719097638, OCLC 961212148

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983), Tolkien, Christopher, ed., The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays, George Allen and Unwin, ISBN 0-04-809019-0 .

- Treschow, Michael; Gill, Paramjit; Swartz, Tim B. (2009), "King Alfred's Scholarly Writings and the Authorship of the First Fifty Prose Psalms", Heroic Age, 12 .

- Vernon, Edward Johnston (1861), A Guide to the Anglo-Saxon Tongue: A Grammar (2nd ed.), London: John Russell Smith

- Woodring, Carl (1995), The Columbia Anthology of British Poetry, p. 1, ISBN 9780231515818 .

- Wrenn, C.L. (1967), A Study of Old English Literature, Norton, ISBN 0393097684 .

Further reading

- Anderson, George K. The literature of the Anglo-Saxons. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966.

- Crépin, André. Old English Poetics: A Technical Handbook. AMAES, hors série 12. Paris, 2005.

- Fulk, R.D. and Christopher M. Cain. A History of Old English Literature. Malden et al.: Blackwell, 2003.

- Godden, Malcolm and Michael Lapidge (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature. Cambridge, 1986.

- Greenfield, Stanley B. and Daniel G. Calder. A New Critical History of Old English Literature. New York: NYU Press, 1986.

- Hamp, Eric P., Lloegr: the Welsh name for England, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, 1982, pp 83–85

- Jackson, Kenneth H.,Varia: I. Bede’s Urbs Giudi: Stirling or Cramond?, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, Winter 1981, pp 1–7

- Jacobs, Nicolas, The Old English heroic tradition in the light of Welsh evidence, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, Winter 1981, pp 9–20

- Jacobs, Nicolas, The Green Knight: an unexplored Irish parallel, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 4, Winter, 1982, pp 1–4

- Pulsiano, Phillip and Elaine Treharne (eds.). A Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature. Oxford et al., 2001.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick, Gildas and the Anglo-Saxons, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 6, Winter 1983, pp 1–30.

- Wright, Charles D., The Irish enumerative style in Old English homiletic literature, especially Vercelli Homily IX, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 18, 1989, pp. 61–76.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old English. |

- An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

- Contemporary Poets read new translations of Anglo-Saxon poems

- The Anglo-Saxon Bible Files in HTML and PDF formats of translations of the Bible (Old and New Testaments) into Anglo-Saxon

- Norton Topics Online An online supplement to the Norton Anthology of English Literature with recordings of Old English Poetry