The Wanderer (poem)

| The Wanderer | |

|---|---|

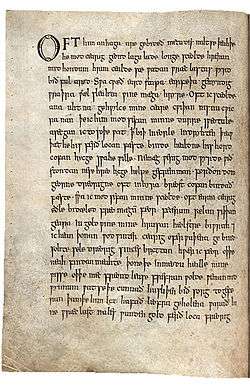

First page of The Wanderer from the Exeter Book | |

| Author(s) | Unknown |

| Language | Old English |

| Date | Impossible to determine[1] |

| Provenance | Exeter Book |

| Genre | Elegy |

| Verse form | Alliterative verse |

| Length | c. 115 lines |

| Personages | The narrator of the "wise man"'s speech, and the "wise man", presumably the "Wanderer" himself. |

The Wanderer is an Old English poem preserved only in an anthology known as the Exeter Book, a manuscript dating from the late 10th century. It counts 115 lines of alliterative verse. As is often the case in Anglo-Saxon verse, the composer and compiler are anonymous, and within the manuscript the poem is untitled.

Origins

The date of the poem is impossible to determine, but it must have been composed and written before the Exeter Book. The poem has only been found in the Exeter Book, which was a manuscript made at around 975, although the poem is considered to have been written earlier.[2] The inclusion of a number of Norse-influenced words, such as the compound hrimceald (ice-cold, from the Old Norse word hrimkaldr), and some unusual spelling forms, has encouraged others to date the poem to the late 9th or early 10th century.[3]

The metre of the poem is of four-stress lines, divided between the second and third stresses by a caesura. Each caesura is indicated in the manuscript by a subtle increase in character spacing and with full stops, but modern print editions render them in a more obvious fashion. Like most Old English poetry, it is written in alliterative metre. It is considered an example of an Anglo-Saxon elegy.[4]

Contents

The Wanderer conveys the meditations of a solitary exile on his past happiness as a member of his lord's band of retainers, his present hardships and the values of forbearance and faith in the heavenly Lord. The warrior is identified as eardstapa (line 6a), usually translated as "wanderer" (from eard meaning 'earth' or 'land', and steppan, meaning 'to step'[5]), who roams the cold seas and walks "paths of exile" (wræclastas). He remembers the days when, as a young man, he served his lord, feasted together with comrades, and received precious gifts from the lord. Yet fate (wyrd) turned against him when he lost his lord, kinsmen and comrades in battle—they were defending their homeland against an attack—and he was driven into exile. Some readings of the poem see the wanderer as progressing through three phases; first as the anhoga (solitary man) who dwells on the deaths of other warriors and the funeral of his lord, then as the modcearig man (man troubled in mind) who meditates on past hardships and on the fact that mass killings have been innumerable in history, and finally as the snottor on mode (man wise in mind) who has come to understand that life is full of hardships, impermanence, and suffering, and that stability only resides with God. Other readings accept the general statement that the exile does come to understand human history, his own included, in philosophical terms, but would point out that the poem has elements in common with "The Battle of Maldon", a poem about a battle in which an Anglo-Saxon troop was defeated by Viking invaders.[6]

However, the speaker reflects upon life while spending years in exile, and to some extent has gone beyond his personal sorrow. In this respect, the poem is a "wisdom poem". The degeneration of “earthly glory” is presented as inevitable in the poem, contrasting with the theme of salvation through faith in God.

The wanderer vividly describes his loneliness and yearning for the bright days past, and concludes with an admonition to put faith in God, "in whom all stability dwells". It has been argued by some scholars that this admonition is a later addition, as it lies at the end of a poem that some would say is otherwise entirely secular in its concerns. Opponents of this interpretation such as I. L. Gordon have argued that because many of the words in the poem have both secular and spiritual or religious meanings, the foundation of this argument is not on firm ground.[7]

The psychological or spiritual progress of the wanderer has been described as an "act of courage of one sitting alone in meditation", who through embracing the values of Christianity seeks "a meaning beyond the temporary and transitory meaning of earthly values".[8]

Interpretation

Critical history

The development of critical approaches to The Wanderer corresponds closely to changing historical trends in European and Anglo-American philology, literary theory, and historiography as a whole.[9]

Like other works in Old English, the rapid changes in the English language after the Norman Conquest meant that it simply would not have been understood between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries.[10] Until the early nineteenth century, the existence of the poem was largely unknown outside of Exeter Cathedral library. In John Josias Conybeare's 1826 compilation of Anglo Saxon poetry, The Wanderer was erroneously treated as part of the preceding poem Juliana.[11] It was not until 1842 that it was identified as a separate work, in its first print edition, by the pioneering Anglo-Saxonist Benjamin Thorpe. Thorpe considered it to bear "considerable evidence of originality", but regretted an absence of information on its historical and mythological context.[12] His decision to name it The Wanderer has not always been met with approval. J. R. R. Tolkien, who adopted elements of the poem into The Lord of the Rings, is typical of such dissatisfaction. By 1926-7 Tolkien was considering the alternative titles 'An Exile', or 'Alone the Banished Man', and by 1964-5 was arguing for 'The Exile's Lament'.[13] Despite such pressure, the poem is generally referred to under Thorpe's original title.

Themes and motifs

A number of formal elements of the poem have been identified by critics, including the use of the "beasts of battle" motif,[14] the ubi sunt formula,[15] the exile theme,[16] the ruin theme,[16] and the siþ-motif.

The "beasts of battle" motif, often found in Anglo-Saxon heroic poetry, is here modified to include not only the standard eagle, raven, and wolf, but also a "sad-faced man". It has been suggested that this is the poem's protagonist.[17]

The ubi sunt or "where is" formula is here in the form "hwær cwom", the Old English phrase "where has gone". The use of this emphasises the sense of loss that pervades the poem.

The preoccupation with the siþ-motif in Anglo-Saxon literature is matched in many post-Conquest texts where journeying is central to the text. A necessarily brief survey of the corpus might include Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and William Golding's Rites of Passage. Not only do we find physical journeying within The Wanderer and those later texts, but a sense in which the journey is responsible for a visible transformation in the mind of the character making the journey.

Speech boundaries

A plurality of scholarly opinion holds that the main body of the poem is spoken as monologue, bound between a prologue and epilogue voiced by the poet. For example, lines 1-5, or 1-7, and 111-115 can be considered the words of the poet as they refer to the wanderer in the third person, and lines 8-110 as those of a singular individual[18] in the first-person. Alternatively, the entire piece can be seen as a soliloquy spoken by a single speaker.[19] Due to the disparity between the anxiety of the 'wanderer' (anhaga) in the first half and the contentment of the 'wise-man' (snottor) in the second half, others have interpreted it as a dialogue between two distinct personas, framed within the first person prologue and epilogue. An alternative approach grounded in post-structuralist literary theory identifies a polyphonic series of different speaking positions determined by the subject that the speaker will address.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Sanders, Arnie. ""The Wanderer," (MS Exeter Book, before 1072)". Goucher College. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Wanderer." The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Julie Reidhead. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2012. 117-118. Print.

- ↑ Klinck 2001, pp. 19, 21

- ↑ Greenblatt, Stephen (2012). The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume A. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-393-91247-0.

- ↑ "eard-stapa". Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary.

- ↑ Donaldson, E. T. "The Battle of Maldon" (PDF). wwnorton.com. W.W. Norton. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Gordon, I.L. (January 1954). "Traditional Themes in the Wanderer and the Seafarer". The Review of English Studies. 5 (17): 1–13. JSTOR 510874.

- ↑ Beaston 2005, p. 134

- ↑ Fulk & Cain 2005, p. 177

- ↑ Stenton 1989

- ↑ Conybeare 1826, p. 204

- ↑ Thorpe 1842, p. vii

- ↑ Lee 2009, pp. 197–198

- ↑ "The Beasts of Battle: Wolf, Eagle, and Raven In Germanic Poetry". www.vikinganswerlady.com.

- ↑ Fulk & Cain 2005, p. 185

- 1 2 Greenfield 1966, p. 215

- ↑ Leslie, R.F. (1966). The Wanderer. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 17.

- ↑ Greenfield & Calder 1986

- ↑ Rumble 1958, p. 229

- ↑ Pasternack 1991, p. 118

Sources

- Beaston, Lawrence (2005). "The Wanderer's Courage". Neophilologus. 89: 119–137. doi:10.1007/s11061-004-5672-x.

- Conybeare, John Josias (1826). Illustrations of Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Harding and Lepard.

- Dunning, T. P.; Bliss, A. J. (1969). The Wanderer. New York. pp. 91–92, 94.

- Fulk, R. D.; Cain, Christopher M. (2005). A History of Old English Literature. Malden: Blackwell.

- Greenfield, Stanley B. (1966). A Critical History of Old English Literature.

- Greenfield, Stanley; Calder, Daniel Gillmore (1986). A New Critical History of Old English Literature. New York: New York University Press.

- Klinck, Anne L. (2001). The Old English Elegies: A Critical Edition and Genre Study.

- Anglo-Saxon poetry: an anthology of Old English poems. Translated by Bradley, S. A. J. London: Dent. 1982. (translation into English prose)

- Lee, Stuart D. (2009). "J.R.R. Tolkien and 'The Wanderer: From Edition to Application'". Tolkien Studies. 6: 189–211.

- Pasternack, Carol Braun (1991). "Anonymous polyphony and The Wanderer's textuality". Anglo-Saxon England. 20: 99–122.

- Rumble, Thomas C. (September 1958). "From Eardstapa to Snottor on Mode: The Structural Principle of 'The Wanderer'". Modern Language Quarterly. 19 (3): 225–230.

- Stenton, Frank (1989). Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thorpe, Benjamin (1842). Codex Exoniensis. A Collection of Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: William Pickering.

External links

- The Wanderer: An Old English Poem Online annotated modern English translation

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Wanderer (poem) |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Wanderer, Anglo-Saxon Aloud. Audio-recording of reading by Michael D.C. Drout.

- The Wanderer Modern English reading by Tom Vaughan-Johnston from YouTube

- The Wanderer Project

- The Wanderer Online text of the poem with modern English translation

- The Wanderer A modern musical setting of the poem

- The Wanderer Online edition with high-res images of the manuscript folios, text, transcription, glossary, and translation by Tim Romano