Nova Scotia in the American Revolution

Nova Scotia was heavily involved in the American Revolution (Nova Scotia included present-day New Brunswick until this colony was created after the war).[1] The American Revolution (1776–1783) had a significant impact on shaping Nova Scotia. At the beginning, there was ambivalence in Nova Scotia, "the 14th American Colony" as some called it, over whether the colony should join the Americans in the war against Britain. Largely as a result of American Privateer attacks on Nova Scotia villages, as the war continued, the population of Nova Scotia solidified their support for the British.

Revolution

1775-1778

At the outbreak of the American Revolution, many Nova Scotians were New England-born and were sympathetic to the American Patriots. This support slowly eroded over the first two years of the war as American Privateers attacked Nova Scotian villages and shipping to try to interrupt Nova Scotian trade with the American Loyalists still in New England. During the war, American Privateers captured 225 vessels either leaving or arriving at Nova Scotia ports.[2] In June 1775, the American's had their first naval victory over the British in the Battle of Machias. In response to this defeat, in July 1775, the British sent from Halifax two armed sloops to Machias to capture the rebels. American privateer Joseph O'Brien captured these two British vessels on 12 July 1775 in the Bay of Fundy.[3] The following month American privateers from Machias executed their third consecutive victory in the region by raiding St John.[4][5]

In retaliation for the American victories at Machias and St. John, the British executed the Burning of Falmouth (present-day Portland, Maine) in October 1775.[6] The following month, in November 1775, the American Patriots retaliated by ships Hancock and Franklin from Marblehead conducting the Raid on Charlottetown (1775) and Canso, Nova Scotia where they took five prizes. The first year of the war ended with the American privateer Raid on Yarmouth, Nova Scotia.[7]

In 1775, rebellion began to ferment within Nova Scotia. Governor Legge began to target prominent protestant dissenters of the St. Matthew's Church: John Fillis and judge William Smith and John Frost (minister). The Governor also targeted judge Seth Harding (judge) from the Liverpool Township and he left on October 1775 and did not return.[8] [9] According to Cahill, as a result of "instances of non-legal repression and petty tyranny, such as the summary dismissals of Judge Smith and Justice Frost, had ended with the recall of Governor Legge [to London] in January 1776."[10]

In 1776, there was also armed rebellion such as the Maugerville Rebellion (1776). The other attack was by land and led by Jonathan Eddy who led the Battle of Fort Cumberland.[7]. According to historian Barry Cahill, this rebellion led the Nova Scotia government to "use the formal law in sedition trials for an essential aspect of the official response to the American Revolution."[11] The government arraigned dissenters John Seccombe and jailed Timothy Houghton for sedition (incitement to rebellion).[12][13] Malachy Salter was convicted of sedition in 1777.

At the end of 1776, there were two significant American attacks on Nova Scotia. One of these assaults was by sea and led by John Paul Jones in the Raid on Canso (1776).

In March 1777, in the first American Navy encounter with the British, the British ran the American vessel a ground in the Battle off Yarmouth (1777) and the privateers escaped to find protection among the local village. The crew found support and the inhabitants of Yarmouth sheltered the American privateers from the British navy until they made their escape back to New England. The engagement between the American privateers and local militia was one of several in the region. On 2 May 1777, in the Minas Basin the Captain Collet ordered the capture the American privateer schooner Sea Duck, under the command of John Bohannan. He had the vessel taken to Windsor.[14] In June, the American Patriots launched the St. John River expedition.[15] In August 1777, the British raided Machias.[16]

The following year, in April 1778 the American privateers again attacked Liverpool. On 9 August, Privateers attacked Cornwallis at present-day Kentville, which resulted in the British building Fort Hughes in the area. The fort could hold 56 soldiers. In 1778, the British schooner Hope also destroyed a privateer ship at Canso. Seven Patriots escaped but were later captured near Halifax.[17] In 1779, Maugerville was raided again by Maliseets working with John Allan in Machias, Maine. A vessel was captured and two or three residents' homes were plundered. In response, a blockhouse was built at the mouth of Oromocto River also named Fort Hughes (New Brunswick) (named after the Lt. Governor of NS Sir Richard Hughes).[18] In June 1779, the British troops at Windsor captured 12 American privateers in the Bay of Fundy, where they cruised in a large boat, armed, plundering the vessels and the inhabitants.[19] In 1779, American privateers returned to Canso and destroyed the fisheries, which were worth £50,000 a year to Britain.[20]

1779-1782

In 1779 the British from Halifax adopted a strategy to seize parts of Maine, especially around Penobscot Bay, and make it a new colony to be called New Ireland. It was intended to be a permanent colony for Loyalists and a base for military action during the war.[21]

In early July 1779, Francis McLean left Halifax and led a British naval and military force into Castine's commodious harbor, landed troops, and took control of the village. He began erecting Fort George on one of the highest points of the peninsula. Alarmed by this incursion, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts sent the Penobscot Expedition to lay side to the fort and reclaim the territory.[22] The siege started on July 25 and lasted three weeks until the arrival of British commander George Collier who crushed the American expedition. (The British held New Ireland, the planned loyalist homeland, until the end of the war. Instead, the British divided Nova Scotia and named the new Loyalist homeland New Brunswick.)[23]

At the end of 1779, the British at Halifax experienced some significant losses. In December 1779 the schooner Hope wrecked near the Sambro Island Light on the Three Sisters Rocks. Captain Henry Baldwin and six other crew were killed. Weeks later, 170 British sailors were lost when two vessels - the North and St. Helena - were wrecked in a storm when entering Halifax harbour.[24][25].

On 10 July 1780, in the Battle off Halifax, the British privateer brig Resolution (16 guns) under the command of Thomas Ross engaged the American privateer Viper (22 guns and 130 men) off Halifax at Sambro Light. In what one observer described as "one of the bloodiest battles in the history of privateering", the two privateers began a "severe engagement"[26] during which both pounded each other with cannon fire for about 90 minutes.[27] The engagement resulted in the surrender of the British ship and the death of up to 18 British and 33 American sailors.[lower-alpha 1][28]

In May 1781, the local Nova Scotia militia defeated American privateers in the Battle off Cape Split.[29] The British and French also clashed in the Naval battle off Cape Breton.[30] Finally, the privateers returned in the Raid on Annapolis Royal (1781).[31] In the final year of attacks on Nova Scotia, the American privateers fought in the Naval battle off Halifax and the Raid on Lunenburg (1782).[32][33]

Defence Regiments

To guard against American privateer attacks, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was garrisoned at forts around Atlantic Canada. Fort Edward (Nova Scotia) in Windsor, Nova Scotia was the Regiment's headquarters to prevent a possible American land assault on Halifax from the Bay of Fundy. Also raised in Nova Scotia were the Royal Fencible American Regiment and the Royal Nova Scotia Volunteer Regiment. The King's Orange Rangers defended Liverpool, the second largest settlement in the colony. The Hessians also served in Nova Scotia for five years (1778–1783). They protected the colony from American privateers, such as when they responded to the Raid on Lunenburg (1782). They were led by Baron Oberst Franz Carl Erdmann von Seitz. There were 5000 British troops in Nova Scotia by 1778.[34]

Naval Defence

In terms of naval force, along with issuing letters of marque for different privateering vessels, in 1776 the Government also retained the armed schooner Loyal Nova Scotian (8 guns, 28 men).[35] On Nov. 26, 1776, under the command of John Alexander, the Loyal Nova Scotian captured the privateer Friendship.[36] In 1778, The vessel was order to Lunenburg and then retired.[37][38] By 1779, Nova Scotia's naval defence had four vessels: a frigate (32 guns), sloop of war (18 guns), armed schooner (14 guns) and another armed schooner (10 guns).[39]

Treaty of Watertown

In 1776, the Mi'kmaq signed the Treaty of Watertown, agreeing to support the American Patriots against the American Loyalists. Three years later, on 7 June 1779, the Mi'kmaq "delivered up" the Watertown treaty to Nova Scotia Governor Michael Francklin and re-established Mi'kmaw loyalty to the British.[40][41] After the British resounding victory over the American Penobscot Expedition, according to Mi'kmaw historian Daniel Paul, Mi'kmaq in present-day New Brunswick renounced the Watertown treated and signed a treaty of alliance with British on 24 September 1779.[42] [43][44]

American Revolution Gallery

Francis McLean established and defended New Ireland (Maine), Plaque, St. Paul's Church (Halifax), Nova Scotia

Francis McLean established and defended New Ireland (Maine), Plaque, St. Paul's Church (Halifax), Nova Scotia

- Hatchment of Baron Oberst Franz Carl Erdmann von Seitz, St. Paul's Church (Halifax), Nova Scotia, d.1782

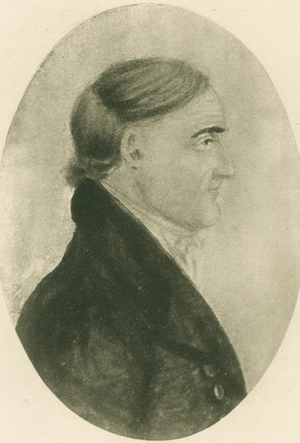

Col Simeon Perkins

Col Simeon Perkins

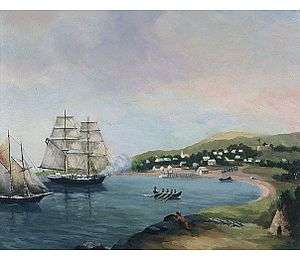

St. John's Island and Newfoundland

The population of St. John's Island (present-day Prince Edward Island), small compared to Nova Scotia, was only about 1215 in 1774.[45] Nova Scotia has been described as a 'shield' to the other two colonies, stopping much unrest from the American colonies from reaching them. St. John's Island during the time has been described as "a model colony".[46]

At the outbreak of the American Revolution, Phillips Callback was in charge of St. Johns Island.[lower-alpha 2] Thomas Gage began recruiting men to help defend Quebec against American attack; however, his efforts were hindered by a group of American revolutionaries living in Pictou, Nova Scotia. A group of about 150 American soldiers set out to attack ships bringing arms to the British.[47] Though they failed in their attempt, they arrived in Pictou, and from the Americans living there learned about recruiting efforts, and attacked Charlottetown. They threatened to set fire to the town but Callback convinced them to spare the town. Callback and Thomas Wright (the surveyor of the island) were taken prisoner.[48][49][50] The two hostages were eventually released, and made it back to the island on May 1, 1776.[51]

After the attack, an armed brig was sent to guard St. John's Island, and a militia was raised. The brig left when the HMS Lizard arrived, and the Lizard in September of 1776. A fort was planned to better defend the town then Fort Amherst could. After Eddy's raid, the militia (which had only existed as 20 men previously) was raised to 80, and named The Loyal Island of St. John Volunteers. In 1778, five companies under Timothy Hierlihy were sent to better garrison the island. At the troops arrival, Callback was ordered to disband the "superfluous and expensive" militia. He ignored the orders. The feasibility of attacking St. John's was considered by the French navy.[52]

The Island, despite perceived danger, served mainly as a stopping point for British troops on their way out from Quebec, and British troops bringing captured privateers back. A group of 200 Hessians en route to Quebec spent a year on the Island. Work on the fort continued until Patterson (the governor) arrived in 1780. He saw the five companies and 8,000 pounds which had been spent on fortifications as a colossal waste of money. Work was halted and the companies returned. Throughout the war, the Island was highly loyal, and endured few attacks.[53]

In 1765, Newfoundlands population was around 15,000, consisting largely of Irish immigrants.[45] As it was not technically a colony, Newfoundland did not pay the Stamp Act 1765 or Townshend Acts taxes. Despite having minor problems with the British government, the island "preserved a tone of exemplary loyalty." The island maintained nearly no defenses, and as such, Esek Hopkins was sent to attack Newfoundland. In September 1776, a group of several privateers took three or four ships, and plundered about ten others. In 1777, the HMS Fox was captured, but was retaken several months later. The following year, many other ships were attacked, particularly by the Minerva.[54]

Upon the arrival of Richard Edwards, many privateers were defeated, and by 1779, very few were left. Edwards ordered cannon distributed to allow towns to defend themselves against attack. In early 1780, at Mortier, a privateer was repulsed by the town. That same year, a fleet, led by Edwards, of nine ships, captured six privateers. Fourteen were captured the next year. Several companies were raised, and several hundred soldiers left to fight with British troops.[55]

Both islands had minor food shortages, particularly after a fire on St. Johns burnt 35 houses, and many stores of food. The fishing industries in both were reduced to "low and miserable state[s]," and the general population of both decreased as well. An outbreak of robberies occurred as people needed various resources. A riot occurred in 1779 on St. John's, in which one person was killed. [55]

Loyalist presence

About 30,000 Loyalists fled to Nova Scotia after the American Revolution ended. Most came from the state of New York.[56] The two largest settlements being Saint John River Valley and Shelburne, Nova Scotia. Cape Breton was a separate colony as received 3150 Loyalists. Ile St. Jean received 300 Loyalist refugees.[57] The British returned New Ireland to the Americans and the territory in Maine entered the control of the newly independent American state of Massachusetts. With the Loyalist homeland gone, Nova Scotia was divided to accommodate the Loyalists: both New Brunswick and Cape Breton were created as separate colonies for the Loyalists (Cape Breton returned to Nova Scotia in 1820). There are many Loyalists buried in the Old Burying Ground (Halifax, Nova Scotia), including a number of Black Loyalists who have unmarked graves.[58] A small number of Nova Scotians went south to serve with the Continental Army against the British; upon the completion of the war these supporters were granted land in the Refugee Tract in Ohio.[59]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ There are varying reports on the number of casualties. Another source indicates that the Americans reported between 3 died (British reporting 30 American died), while British reported 8 killed and 10 wounded.

- ↑ The governor was on a trip to England, and Callback, the Attorney General was left in charge

Sources

- ↑ Hanc, John. "When Nova Scotia Almost Joined the American Revolution". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ↑ Julian Gwyn. Frigates and Foremasts. University of British Columbia. 2003. p. 56

- ↑ EDGAR STATION MACLAY (1899). A HISTORY OF AMERICAN PRIVATEERS. Universal Digital Library. D. APPLENTON AND COMPANY.

- ↑ Naval Documents of the American Revolution, p. pp. 445-446

- ↑ For other reasons why Nova Scotia didn't join in the rebellion see: Barry Cahill, "The Treason of the Merchants: Dissent and Repression in Halifax in the Era of the American Revolution," Acadiensis 1996 26(1): 52-70; G. Stewart, and G. Rawlyk, A People Highly Favoured of God: The Nova Scotia Yankees and the American Revolution (1972); Maurice Armstrong, "Neutrality and Religion in Revolutionary Nova Scotia," The New England Quarterly v19, no. 1 (1946): 50-62 in JSTOR

- ↑

- Burke, Edmund (1780). An Impartial History of the War in America. London: R. Faulder. OCLC 6187693.

- 1 2 Faibisy 2014

- ↑ https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-13-02-0197

- ↑ Cahill, p. 52

- ↑ Cahill, p. 54

- ↑ Barry Cahill. The Treason of the Merchants: Dissent and Repression in Halifax in the Era of the American Revolution. Acadiensis. 24, (Autumn 1996), pp. 54.

- ↑ John Frost

- ↑ John Frost 2

- ↑ p. 75

- ↑ Raymond, William O (1905). Glimpses of the Past: History of the River St. John. Saint John, NB: unspecified. OCLC 422037263.

- ↑ Mancke, Elizabeth (2005). The Fault Lines of Empire: Political Differentiation in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, ca. 1760–1830. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95000-8.

- ↑ p.17

- ↑ Hannay, p. 121-122

- ↑ p.600

- ↑ Lieutenant Governor Sir Richard Hughes stated in a dispatch to Lord Germaine that "rebel cruisers" made the attack.

- ↑ Robert W. Sloan, "New Ireland: Men in Pursuit of a Forlorn Hope, 1779-1784," Maine Historical Society Quarterly, 1979, Vol. 19 Issue 2, pp 73-90

- ↑ Bicheno, Hugh (2003). Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolutionary War. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-715625-2. OCLC 51963515.

- ↑ Beamish Murdoch (1866). A History of Nova Scotia, Or Acadie. unknown library. J. Barnes.

- ↑ p. 78

- ↑ Beamish Murdoch (1866). A History of Nova Scotia, Or Acadie. unknown library. J. Barnes.

- ↑ Simeon Perkins Diary. Thursday 13 July 1780

- ↑ Bandits and Privateers: Canada in the Age of Gunpowder; Beamish Murdoch A history of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie, Vol. 2, p.608.

- ↑ Beamish Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia, Vol. 2, p. 608

- ↑ Beamish Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia, Vol. 2, p.614 History of Kings County, Nova Scotia. p. 433

- ↑ Gwyn, Julian (2004), Frigates and Foremasts: The North American Squadron in Nova Scotia. Waters, 1745–1815, UBC Press.

- ↑ Brenda Dunn. A History of Port Royal, Annapolis Royal. Nimbus Publishing. 2004. pp. 222-223

- ↑ Salem Gazette, 11, 18 July 1782; Boston Post, 15 June 1782; and Hunt's Magazine, February, 1857, as cited by Gardner W. Allen, A NAVAL HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION (Boston, 1913), Chapter 17.

- ↑ MacMechan, Archibald (1923), “The Sack of Lunenburg” in Sagas of the Sea. The Temple Press, pp. 57–72.

- ↑ Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia. p.594

- ↑ https://archives.gnb.ca/exhibits/forthavoc/html/nova-scotia-privateers.aspx?culture=en-CA

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/americanvesselsc00nova/page/33

- ↑ p. 122

- ↑ https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015068749905;view=1up;seq=458

- ↑ p. 602

- ↑ Michael Francklin, p. 282

- ↑ Beamish Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia, p. 599

- ↑ Daniel N. Paul, We Were Not the Savages: A Mi'kmaq Perspective on the Collision between European and Native American Civilizations (2000), pp. 169-170 (includes full text of both treaties).

- ↑ Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia, p. 595

- ↑ John Allen re: Watertown, p.318

- 1 2 Kerr 1941, pp. 9-10

- ↑ Kerr 1941, p. 105

- ↑ Kerr 1941, p. 106

- ↑ Privateering and Piracy. The effects of New England Raiding upon Nova Scotia during the Revolutionary War, 1972, p. 43

- ↑ Coffin's wife Elizabeth Barnes.

- ↑ Stark, James Henry (1972). The Loyalists of Massachusetts And the Other Side of the American Revolution. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 9781465573919.

- ↑ Kerr 1941, p. 107

- ↑ Kerr 1941, pp. 107-108

- ↑ Kerr 1941, pp. 109-111

- ↑ Kerr 1941, pp. 111–114

- 1 2 Kerr 1941, pp. 115–123

- ↑ Loyalism in New York, p. 176

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/loyalismnewyork00flicrich#page/174/mode/1up/search/nova+scotia

- ↑ "Loyalists / Black Loyalists".

- ↑ ""Refugee Tract"". Papers of the War Department. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

Bibliography

- Kerr, Wilfred Brenton (1941). The maritime provinces of British North America and the American Revolution. Sackville, N.B.: Busy East Press.

- Rawlyk, George A. "The American Revolution and Nova Scotia Reconsidered". The Dalhousie Review: 379–394.

- Cahill, Barry (Autumn 1996). "The Treason of the Merchants: Dissent and Repression in Halifax in the Era of the American Revolution". Acadiensis: 52–70.

- Faibisy, John Dewar (February 2014). "Privateering and piracy : the effects of New England raiding upon Nova Scotia during the American Revolution, 1775-1783". Doctoral Dissertations 1896.