Nigrostriatal pathway

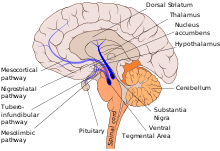

The nigrostriatal pathway or the nigrostriatal bundle (NSB), is a dopaminergic pathway that connects the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) with the dorsal striatum (i.e., the caudate nucleus and putamen). It is one of the four major dopamine pathways in the brain, and is particularly involved in the production of movement, as part of a system called the basal ganglia motor loop. Dopaminergic neurons of this pathway synapse onto GABAergic neurons.[1]

Loss of dopamine neurons in the SNc is one of the main pathological features of Parkinson's disease,[2] leading to a marked reduction in dopamine function in this pathway. Depletion of neurons in this pathway lead to the symptomatic motor deficits of Parkinson's disease including tremors, rigidity, and postural imbalance.

Anatomy

The following are considered part of the nigrostriatal pathway.

Substantia nigra pars compacta

The substantia nigra is located in the midbrain. It has two distinct parts, the pars compacta and the pars reticulata. The pars compacta is part of the nigrostriatal pathway and relays information to the basal ganglia by supplying dopamine to the striatum. The pars reticulata in conjunction with the globus pallidus in the basal ganglia allows for inhibition of the thalamus.

Dorsal striatum

The dorsal striatum is located in the subcortical region of the forebrain. It is divided by a white matter tract called the internal capsule into two parts: the putamen and the caudate nucleus. The putamen and caudate both input information from the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and substantia nigra.

Function

The nigrostriatal pathway connects the SNc with the dorsal striatum. It is one of the four major dopamine pathways in the brain, and is particularly involved in modulation of the extrapyramidal system. Dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway synapse onto GABAergic neurons in the basal ganglia.[1] and in part make up the basal ganglia motor loop. Along with the other dopaminergic pathways, it is also partially involved in reward and in the reinforcement of memory consolidation.[3]

The nigrostriatal pathway influences two other pathways, the direct pathway of movement and the indirect pathway of movement.

Direct pathway of movement

The direct pathway is involved in facilitation of wanted movements. The projections of the caudate, putamen, internal segment of the globus pallidus, and the SNc create an excitatory effect on the thalamus by decreasing the GABA released by the striatum. This inhibitory effect decreases inhibitory projections from the thalamus, creating an overall net excitatory effect.

Indirect pathway of movement

The indirect pathway is involved in preventing unwanted movement. The projections of the caudate, putamen, external segment of the globus pallidus, and substantia nigra pars reticulata create an inhibitory effect on the thalamus through the release of GABA. This inhibitory effect decreases the excitatory projections from the thalamus, creating an overall net inhibitory effect on movement.

Clinical significance

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is characterized by severe motor problems, mainly hypokinesia, rigidity, tremors, and postural imbalance.[4] Loss of dopamine neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway is one of the main pathological features of Parkinson's disease.[5] Degeneration of dopamine producing neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the putamen-caudate complex leads to diminished concentrations of dopamine in the nigrostriatal pathway, leading to reduced function and the characteristic symptoms.[6] The symptoms of the disease typically do not show themselves until 80-90% of dopamine function has been lost.

Levodopa-induced dyskinesia

Levodopa-induced dyskinesias (LID) is a complication associated with long-term use of the Parkinson's treatment L-DOPA characterized by involuntary movement and muscle contractions. This disorder occurs in up to 90% of patients after 9 years of treatment. The use of L-DOPA in patients can lead to interruption of nigrostriatal dopamine projections as well as changes in the post-synaptic neurons in the basal ganglia.[7]

Schizophrenia

Presynaptic dopamine metabolism is altered in schizophrenia.[8][9]

Other dopamine pathways

Other major dopamine pathways include:

See also

References

- 1 2 Tritsch, NX; Ding, JB; Sabatini, BL (Oct 2012). "Dopaminergic neurons inhibit striatal output through non-canonical release of GABA". Nature. 490 (7419): 262–6. doi:10.1038/nature11466. PMC 3944587. PMID 23034651.

- ↑ Diaz, Jaime. How Drugs Influence Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1996.

- ↑ Wise, RA (October 2009). "Roles for nigrostriatal--not just mesocorticolimbic--dopamine in reward and addiction". Trends in Neurosciences. 32 (10): 517–524. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.004. PMC 2755633. PMID 19758714.

- ↑ Cenci, Angela M (2006). "Post- versus presynaptic plastic ity in L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia". Journal of Neurochemistry. 99 (2): 381–92. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04124.x. PMID 16942598.

- ↑ Deumens, Ronald (21 June 2002). "Modeling Parkinson's Disease in Rats: An Evaluation of 6-OHDA Lesions of the Nigrostriatal Pathway". Experimental Neurology. 175 (2): 303–17. doi:10.1006/exnr.2002.7891. PMID 12061862.

- ↑ Groger, Adraine (8 January 2014). "Dopamine Reduction in the Substantia Nigra of Parkinson's Disease Patients Confirmed by In Vivo Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging". PLoS ONE. 9: e84081. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084081. PMC 3885536. PMID 24416192.

- ↑ Niethammer, Martin (May 2012). "Functional Neuroimaging in Parkinson's Disease". Cold Spring Harbors Perspect in Medicin. 2 (5): a009274. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a009274. PMC 3331691. PMID 22553499.

- ↑ Fusar-Poli, Paolo; Meyer-Lindenberg, Andreas (1 January 2013). "Striatal presynaptic dopamine in schizophrenia, part II: meta-analysis of [(18)F/(11)C]-DOPA PET studies". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 39 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbr180. ISSN 1745-1701. PMC 3523905. PMID 22282454.

- ↑ Weinstein, Jodi J.; Chohan, Muhammad O.; Slifstein, Mark; Kegeles, Lawrence S.; Moore, Holly; Abi-Dargham, Anissa (1 January 2017). "Pathway-Specific Dopamine Abnormalities in Schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.03.2104. ISSN 1873-2402. PMC 5177794. PMID 27206569.