Ngunnawal

The Ngunawal are an indigenous Australian people of southern New South Wales.

Language

Ngunawal, known also as Gundungurra or Burragorang, is classified, together with Ngarigo as one of two southern tableland languages of New South Wales.[1]

Country

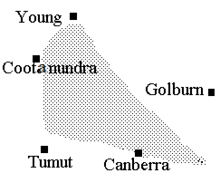

Norman Tindale claimed that Ngunawal territory, which he estimated to cover some 800 square miles (2,100 km2), extended from Queanbeyan to Yass, Tumut and Boorowa, with its eastern extension beyond Goulburn. He also placed them on the western side of the Shoalhaven River, in the highlands.[2] In earlier ethnographer R. H. Mathews placed them from Goulburn to Yass and Burrowa southwards as far as Lake George and Goodradigbee.[3]

Like much of Tindale's mapping, this topographic description's accuracy has been questioned. Recent research by Harold Koch (2011) and others shows that the Ngunwal country was primarily the land surrounding the Yass River extending between Lake George to the east and the Murrumbidgee to the west, while the southern boundary of the Ngunwal people was north of Canberra, approximately on a line from Gundaroo to Wee Jasper.

However, as detailed in the 2013 genealogical report by Dr Natalie Knok to the ACT Government for their project "Our Kin Our Country", there has been growth in the number of "new tribes" in the context of claims to country and land management in the current legal context. An example is the use of the traditional Nganawal language to propose in 1996 the existence of the new tribe "Ngannwal" with a substantial county, including Canberra, Goulburn, Queanbeyan, Tumut and Yass. The report concluded that with "the paucity of the written record it may be assumed that the issue of which groups held traditional association over which areas will remain uncertain".

People

When first encountered by European settlers in the 1820s, the Ngunawal were called the Yass Blacks or Yass mob with a reputation for hostility. The Ngunawal people were neighbours of the Nyamudy/Namadgi (who lived to the south on the Limestone Plains), Wiradjuri (to the west) and Gundungurra (to the north) peoples. However an alternative view is that Ngunnawal was not a tribe but the southern dialect of the Wallaballoa clan whose territory extended north from Yass to Baorowa.

The 2013 report to the ACT Government as part of its "Our Kin, Our Country" project accepted that based on the difference between word lists collected at Yass and the Limestone Plain, the people of the Canberra area were Ngarigo speaking Nyamudy/Namadgi people not Ngunnawal people. Some Ngunnawal people speak of their group as constituted by several clan groups, such as the Wallababul around Yass, the Ginninderra and the Pialligo.[4]

The report "Our Kin Our Country" on the connection to the area by present-day ACT Aboriginal inhabitants, concluded:

Therefore there appears to be no surviving traditional knowledge of lore, language, custom, kinship structures, oral history and genealogy associated directly with the ACT which would form the basis of a connection report. ... the historical record of Aboriginal culture and populations is very scant and contradictory, it was recognised that it would not be possible to prepare a full "connection to country" report linking present day people through their families and surviving traditional knowledge to the past land holding groups.[5]

Dispute over the traditional ownership of Canberra and the surrounding region

At present four groups contest ownership in the Canberra area: the Ngambri, the Ngarigo, the Walgalu speaking Ngambri-Guumaal, represented by Shane Mortimer, with widespread connections from across the Snowy Mountains down to the Blue Mountains, and fourthly, the Ngunnawal.[4]

According to recollection of settlers living in the area in the 1830s, such as quoted in the Quenbeyan Age, there were three groups in the region, the Yass Blacks (Ngunnawal), the Limestone Blacks (Nyamudy/Namadgi) and the Monaro Blacks (Ngarigo). Battles for ownership of the territory took place at Goondaroo/Sutton with the Yass Blacks and at Pialigo with the Monaro Blacks, in both cases the Nyamudy/Namadgi tribe won to retain first ownership of the Canberra district.

The present dispute originated when Tindall in his 1940 map incorrectly drew its boundaries with that of Ngarigo. In 2005, in response to a question in the ACT Legislative Assembly about the status of the Ngambri people, the Chief Minister at the time, Jon Stanhope, inaccurately stated that "Ngambri is the name of one of a number of family groups that make up the Ngunnawal nation." He went on to say that "the Government recognises members of the Ngunnawal nation as descendants of the original inhabitants of this region."

In 2012 research for the ACT Governments One Kin One Country found "there is no basis within the description of country supplied by Tindale, or in the original sources". The research confirmed that the language spoken in the Canberra region was a dialect of Ngarigu, "related to but distinguishable from the dialects spoken at Tumut and Monaro". The report stated that evidence gathered from the mid-1700s onward was too scant to support any family's claims to be original owners.[6]

Some Canberra-area people with Aboriginal heritage in inland SE Australia, including Matilda House identify as Ngambri. Shane Mortimer defines himself as one of the Ngambri-Guumwaal, -Guumaal being a language name said to mean "high country".[4] This claim to be a distinct nation is disputed by many other local Aboriginal people who say that the Ngambri are a small family clan of the Wiradjuri nation who took their name from a creek located on Black Mountain in the late 1990s.[7]

Native title

The earliest direct evidence for Indigenous occupation in the area comes from a rock shelter near the area of Birrigai near Tharwa, which has been dated to approximately 20,000 years ago. However, it is likely (based on older sites known from the surrounding regions) that human occupation of the region goes back considerably further.

They were gradually displaced from the Yass area beginning in the 1820s when graziers began to occupy the land there. Some people worked at properties in the region. In 1826 many Aborigines at Lake George protested an incident involving a shepherd and Aboriginal woman, though the protesters moved away peacefully.

Some histories of Australia record the last full-blooded Ngunnawal person, Nellie Hamilton, dying in 1897. However, it has been regarded by some Indigenous Australians as a biased attempt to claim that they were wiped out when there are many Ngunnawal people still around today.[8]

In spite of the historical record, there has been little success in gaining native title in the Yass area, and no success in the ACT when combined with Aboriginals from other tribal connections.

Notes

- ↑ This map is indicative only.

Citations

- ↑ Dixon 2002, p. xxxv.

- ↑ Tindale 1974, p. 198.

- ↑ Mathews 1904, p. 294.

- 1 2 3 Osborne 2016.

- ↑ OKOC 2012.

- ↑ Towell 2013.

- ↑ ABC Australia 2005.

- ↑ McKeon 1995.

Sources

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47378-1.

- "The Future of the Tent Embassy". ABC Australia. 25 November 2005. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008.

- Kwok, Natalie (January 2013). Considering traditional Aboriginal affiliations in the ACT region: Draft Report (PDF). ACT government.

- Mathews, R. H. (1904). "The Wiradyuri and Other Languages of New South Wales". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 34 (July–December): 284–305. JSTOR 2843103.

- McKeon, Rosemarie (20 October 1995). "SCULPTURE FORUM 95: ABORIGINAL ART at the Canberra Contemporary Art Space". Archived from the original on 6 September 2004.

- Osborne, Tegan (28 April 2016). "What is the Aboriginal history of Canberra?". ABC News.

- "Our Kin Our Country" (pdf). ACT Government Genealogy Project. August 2012.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Ngunawal (NSW)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Towell, Noel (9 April 2013). "Canberra's first people still a matter for debate". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013.