Neanderthal extinction

Neanderthal extinction began around 40,000 years ago in Europe, after anatomically modern humans had reached the continent. This date, which is based on research published in Nature in 2014, is much earlier than previous estimates, and it was established through improved radio carbon dating methods analyzing 40 sites from Spain to Russia. The survey did not include sites in Asia, where Neanderthals may have survived longer.[1]

Hypotheses on the fate of the Neanderthals include violence from encroaching anatomically modern humans,[2] parasites and pathogens, competitive replacement, competitive exclusion, extinction by interbreeding with early modern human populations,[3] and failure or inability to adapt to climate change. It is unlikely that any one of these hypotheses is sufficient on its own; rather, multiple factors probably contributed to the demise of an already widely-dispersed population.[4][5]

Coexistence prior to extinction

In research published in Nature in 2014, an analysis of radiocarbon dates from forty Neanderthal sites from Spain to Russia found that the Neanderthals disappeared in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago with 95% probability. The study also found with the same probability that modern humans and Neanderthals overlapped in Europe for between 2,600 and 5,400 years.[1] Modern humans reached Europe between 45,000 and 43,000 years ago.[6] Most recent numbers based on improved radiocarbon dating indicate that Neanderthals disappeared around 40,000 years ago, which overturns older carbon dating which indicated that Neanderthals may have lived as recently as 24,000 years ago,[7] including in refugia on the south coast of the Iberian peninsula such as Gorham's Cave.[8][9] Inter-stratification of Neanderthal and modern human remains has been suggested,[10] but is disputed.[11]

Possible cause of extinction

Violence

Some authors have discussed the possibility that Neanderthal extinction was either precipitated or hastened by violent conflict with Homo sapiens. Conflict and warfare are virtually ubiquitous features of hunter-gatherer societies, including conflicts over limited resources, such as prey and water.[12] It is therefore plausible to suggest that violence, including primitive warfare, would have transpired between the two human species.[13] The hypothesis that early humans violently replaced Neanderthals was first proposed by French palaeontologist Marcellin Boule (the first person to publish an analysis of a Neanderthal) in 1912.[14] Several finds in both Homo-sapiens and Neanderthal bones indicate inter-species aggression from injuries (grooves in the bones themselves) that could only have come from spear or other projectile tips crafted with prevalent tool-making methods contemporary to the time.[15]

Parasites and pathogens

Another possibility is the spread among the Neanderthal population of pathogens or parasites carried by Homo sapiens.[16] Neanderthals would have limited immunity to diseases they had not been exposed to, so diseases carried into Europe by Homo sapiens could have been particularly lethal to them if Homo sapiens were relatively resistant. If it were relatively easy for pathogens to leap between these two similar species, perhaps because they lived in close proximity, then Homo sapiens would have provided a pool of individuals capable of infecting Neanderthals and potentially preventing the epidemic from burning itself out as Neanderthal population fell. On the other hand, the same mechanism could work in reverse, and the resistance of Homo sapiens to Neanderthal pathogens and parasites would need explanation. An examination of human and Neanderthal genomes and adaptations regarding pathogens or parasites may shed light on this issue.

Competitive replacement

Species specific disadvantages

Slight competitive advantage on the part of modern humans has accounted for Neanderthals' decline on a timescale of thousands of years.[17]

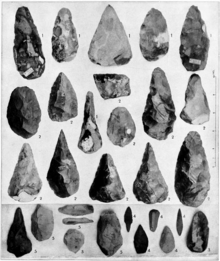

Generally small and widely-dispersed fossil sites suggest that Neanderthals lived in less numerous and socially more isolated groups than contemporary Homo sapiens. Tools such as Mousterian flint stone flakes and Levallois points are remarkably sophisticated from the outset, yet they have a slow rate of variability and general technological inertia is noticeable during the entire fossil period. Artifacts are of utilitarian nature, and symbolic behavioral traits are undocumented before the arrival of modern humans in Europe around 40,000 to 35,000 years ago.[18][19]

Jared Diamond, supporter of competitive replacement, points out in his book The Third Chimpanzee that the genocidal replacement of Neanderthals by modern humans is comparable to patterns of behavior that occur whenever people with advanced technology clash with less advanced people.[20]

Division of labor

In 2006, two anthropologists of the University of Arizona proposed an efficiency explanation for the demise of the Neanderthals.[21] In an article titled "What's a Mother to Do? The Division of Labor among Neanderthals and Modern Humans in Eurasia",[22] it was posited that Neanderthal division of labor between the sexes was less developed than Middle paleolithic Homo sapiens. Both male and female Neanderthals participated in the single occupation of hunting big game, such as bison, deer, gazelles and wild horses. This hypothesis proposes that the Neanderthal's relative lack of labor division resulted in less efficient extraction of resources from the environment as compared to Homo sapiens.

Anatomical differences and running ability

Researchers such as Karen L. Steudel of the University of Wisconsin have highlighted the relationship of Neanderthal anatomy (shorter and stockier than that of modern humans) and the ability to run and the requirement of energy (30% more).[23]

Nevertheless, in the recent study, researchers Martin Hora and Vladimir Sladek of Charles University in Prague show that Neanderthal lower limb configuration, particularly the combination of robust knees, long heels and short lower limbs, increased the effective mechanical advantage of Neanderthal knee and ankle extensors, thus reducing the force needed and the energy spent for locomotion significantly. The walking cost of the Neanderthal male is now estimated to be 8–12% higher than that of anatomically modern males, whereas the walking cost of the Neanderthal female is considered to be virtually equal to that of anatomically modern females.[24]

Other researchers, like Yoel Rak, from Tel-Aviv University in Israel, have noted that the fossil records show that Neanderthal pelvises in comparison to modern human pelvises would have made it much harder for Neanderthals to absorb shock and to bounce off from one step to the next, giving modern humans another advantage over Neanderthals in running and walking ability.[25]

Modern humans' advantage in hunting warm climate animals

Pat Shipman, from Pennsylvania State University in the United States, argues that the domestication of the dog gave modern humans an advantage when hunting.[26] The oldest remains of domesticated dogs were found in Belgium (31,700 BP) and in Siberia (33,000 BP).[27][28] A survey of early sites of modern humans and Neanderthals with faunal remains across Spain, Portugal and France provided an overview of what modern humans and Neanderthals ate.[29] Rabbit became more frequent, while large mammals – mainly eaten by the Neanderthals – became increasingly rare. In 2013, DNA testing on the "Altai dog", a paleolithic dog's remains from the Razboinichya Cave (Altai Mountains), has linked this 33,000-year-old dog with the present lineage of Canis lupus familiaris.[30]

Interbreeding

Interbreeding can only account for a certain degree of Neanderthal population decrease. A homogeneous absorption of an entire species is a rather unrealistic idea. This would also be counter to strict versions of the Recent African Origin, since it would imply that at least part of the genome of Europeans would descend from Neanderthals, who left Africa at least 350,000 years ago.

The most vocal proponent of the hybridization hypothesis is Erik Trinkaus of Washington University.[31][32] Trinkaus claims various fossils as hybrid individuals, including the "child of Lagar Velho", a skeleton found at Lagar Velho in Portugal.[33] In a 2006 publication co-authored by Trinkaus, the fossils found in 1952 in the cave of Peștera Muierilor, Romania, are likewise claimed as hybrids.[34]

Genetic studies indicate some form of hybridization between archaic humans and modern humans had taken place after modern humans emerged from Africa. An estimated 1–4% of the DNA in Europeans and Asians (e.g. French, Chinese and Papua probands) is non-modern, and shared with ancient Neanderthal DNA rather than with sub-Saharan Africans (e.g. Yoruba and San probands).[35]

Modern-human findings in Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Portugal allegedly featuring Neanderthal admixtures have been published.[36] However, the interpretation of the Portuguese specimen is disputed.[37]

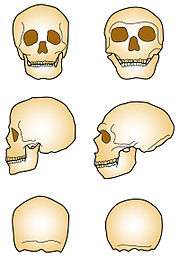

Jordan, in his work Neanderthal, points out that without some interbreeding, certain features on some "modern" skulls of Eastern European Cro-Magnon heritage are hard to explain. In another study, researchers have recently found in Peştera Muierilor, Romania, remains of European humans from ~37,000–42,000 years ago[38]who possessed mostly diagnostic "modern" anatomical features, but also had distinct Neanderthal features not present in ancestral modern humans in Africa, including a large bulge at the back of the skull, a more prominent projection around the elbow joint, and a narrow socket at the shoulder joint. Analysis of one skeleton's shoulder showed these humans, like Neanderthals, did not have the full capability for throwing spears.[39]

The Neanderthal genome project published papers in 2010 and 2014 stating that Neanderthals contributed to the DNA of modern humans, including most humans outside sub-Saharan Africa, as well as a few populations in sub-Saharan Africa, through interbreeding, likely between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.[40][41][42] Recent studies also show that a few Neanderthals began mating with ancestors of modern humans long before the large "out of Africa migration" of the present day non-Africans, as early as 100,000 years ago.[43] In 2016, research indicated that there were three distinct episodes of interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals: the first encounter involved the ancestors of non-African modern humans, probably soon after leaving Africa; the second, after the ancestral Melanesian group had branched off (and subsequently had a unique episode of interbreeding with Denisovans); and the third, involving the ancestors of East Asians only.[44]

While interbreeding is viewed as the most parsimonious interpretation of the genetic discoveries, the authors point out they cannot conclusively rule out an alternative scenario, in which the source population of non-African modern humans was already more closely related to Neanderthals than other Africans were, due to ancient genetic divisions within Africa.

Among the genes shown to differ between present-day humans and Neanderthals were RPTN, SPAG17, CAN15, TTF1 and PCD16.

Climate change

Neanderthals went through a demographic crisis in Western Europe that seems to coincide with climate change that resulted in a period of extreme cold in Western Europe. "The fact that Neanderthals in Western Europe were nearly extinct, but then recovered long before they came into contact with modern humans came as a complete surprise to us," said Love Dalén, associate professor at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. If so, this would indicate that Neanderthals may have been very sensitive to climate change.[45]

Natural catastrophe

A number of researchers have argued that the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption, a volcanic eruption near Naples, Italy, about 39,280 ± 110 years ago (older estimate ~37,000 years), erupting about 200 km3 (48 cu mi) of magma (500 km3 (120 cu mi) bulk volume) has contributed to the extinction of Neanderthal man.[46] The argument has been developed by Golovanova et al.[47][48]

Although Neanderthals had encountered several Interglacials during 250,000 years in Europe[49] inability to adapt their hunting methods caused their extinction facing H. sapiens competition when Europe changed into a sparsely vegetated steppe and semi-desert during the last Ice Age.[50] Studies of sediment layers at Mezmaiskaya Cave suggest a severe reduction of plant pollen.[48] The damage to plant life would have led to a corresponding decline in plant-eating mammals hunted by the Neanderthals.[48][51][52]

See also

References

- 1 2 Higham, Tom; et al. (21 August 2014). "The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance". Nature. 512 (7514): 306–309. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..306H. doi:10.1038/nature13621. PMID 25143113.

- ↑ Hortolà P, Martínez-Navarro B (2013). "The Quaternary megafaunal extinction and the fate of Neanderthals: An integrative working hypothesis". Quaternary International. 295: 69–72. Bibcode:2013QuInt.295...69H. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.037.

- ↑ Interbreeding took place in western Asia between about 65,000 and 47,000 years ago, see Kuhlwilm, M.; Gronau, I.; Hubisz, M.J.; de Filippo, C.; Prado-Martinez, J.; Kircher, M.; et al. (2016). "Ancient gene flow from early modern humans into Eastern Neanderthals". Nature. 530 (7591): 429–433. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..429K. doi:10.1038/nature16544. PMC 4933530. PMID 26886800.

- ↑ "What Are Those Darned Neanderthals Up to Now?". Anthropology in practice. October 11, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Did a Volcanic Eruption Kill Off the Neandertals?". Science for writers. March 25, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ↑ John Noble Wilford (2011-11-02). "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ Dorey, Fran (30 October 2015). "Homo Neanderthalensis – The Neanderthals". Australian Museum. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (13 September 2006). "Neanderthals' 'last rock refuge'". BBC News. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ↑ Finlayson C, Pacheco FG, Rodríguez-Vidal J, et al. (October 2006). "Late survival of Neanderthals at the southernmost extreme of Europe". Nature. 443 (7113): 850–853. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..850F. doi:10.1038/nature05195. hdl:10261/18685. PMID 16971951.

- ↑ Gravina B, Mellars P, Ramsey CB (November 2005). "Radiocarbon dating of interstratified Neanderthal and early modern human occupations at the Chatelperronian type-site". Nature. 438 (7064): 51–56. Bibcode:2005Natur.438...51G. doi:10.1038/nature04006. PMID 16136079.

- ↑ Zilhão, João; Francesco d’Errico; Jean-Guillaume Bordes; Arnaud Lenoble; Jean-Pierre Texier; Jean-Philippe Rigaud (2006). "Analysis of Aurignacian interstratification at the Châtelperronian-type site and implications for the behavioral modernity of Neandertals". PNAS. 103 (33): 12643–12648. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312643Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605128103. PMC 1567932. PMID 16894152.

- ↑ Hawks, John. "Hunter-gatherer mortality". john hawks weblog. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Ko, Kwang Hyun (2016). "Hominin interbreeding and the evolution of human variation". Journal of Biological Research-Thessaloniki. 23: 17. doi:10.1186/s40709-016-0054-7. PMC 4947341. PMID 27429943.

- ↑ Boule, M 1920, Les hommes fossiles, Masson, Paris.

- ↑ "Human Stabbed a Neanderthal, Evidence Suggests". Livescience.com. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ↑ Underdown, Simon (10 April 2015). "Brookes research finds modern humans gave fatal diseases to Neanderthals". Oxford Brookes University news. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Banks, William E.; d'Errico, Francesco; Peterson, A. Townsend; Kageyama, Masa; Sima, Adriana; Sánchez-Goñi, Maria-Fernanda (24 December 2008). Harpending, Henry, ed. "Neanderthal Extinction by Competitive Exclusion". PLoS ONE. 3 (12): e3972. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3972B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003972. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2600607. PMID 19107186.

- ↑ "Homo neanderthalensis Brief Summary". EOL. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Peresani, M; Dallatorre, S; Astuti, P; Dal Colle, M; Ziggiotti, S; Peretto, C (2014). "Symbolic or utilitarian? Juggling interpretations of Neanderthal behavior: new inferences from the study of engraved stone surfaces". J Anthropol Sci. 92: 233–55. doi:10.4436/JASS.92007. PMID 25020018.

- ↑ Diamond, J. (1992). The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal. New York: Harper Collins, p. 45.

- ↑ Nicholas Wade, "Neanderthal Women Joined Men in the Hunt", from The New York Times, 5 December 2006

- ↑ Kuhn, Steven L.; Stiner, Mary C. (2006). "What's a Mother to Do? The Division of Labor among Neandertals and Modern Humans in Eurasia". Current Anthropology. 47 (6): 953–981. doi:10.1086/507197.

- ↑ Steudel, Karen L. (2009). "Karen L. Steudel". Madison, Wisconsin: Department of Zoology – University of Wisconsin. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- ↑ Hora, M; Sládek, V (2014). "Influence of lower limb configuration on walking cost in Late Pleistocene humans". Journal of Human Evolution. 67: 19–32. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.011. PMID 24485350.

- ↑ Lewin, Roger (27 April 1991). "Science: Neanderthals puzzle the anthropologists". New Scientist. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ↑ Shipman, P (2012). "Dog domestication may have helped humans thrive while Neandertals declined". American Scientist. 100 (3): 198.

- ↑ Ovodov, ND; Crockford, SJ; Kuzmin, YV; Higham, TFG; Hodgins, GWL; et al. (2011). "A 33,000-Year-Old Incipient Dog from the Altai Mountains of Siberia: Evidence of the Earliest Domestication Disrupted by the Last Glacial Maximum". PLoS ONE. 6 (7): e22821. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622821O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022821. PMC 3145761. PMID 21829526.

- ↑ Germonpré, M.; Sablin, M.V.; Stevens, R.E.; Hedges, R.E.M.; Hofreiter, M.; Stiller, M.; Jaenicke-Desprese, V. (2009). "Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (2): 473–490. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033.

- ↑ Fa, John E.; Stewart, John R.; Lloveras, Lluís; Vargas, J. Mario (2013). "Rabbits and hominin survival in Iberia". Journal of Human Evolution. 64 (4): 233–241. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.01.002. PMID 23422239.

- ↑ Druzhkova, AS; Thalmann, O; Trifonov, VA; Leonard, JA; Vorobieva, NV; et al. (2013). "Ancient DNA Analysis Affirms the Canid from Altai as a Primitive Dog". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e57754. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857754D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057754. PMC 3590291. PMID 23483925.

- ↑ Jones, Dan (2007). "The Neanderthal within". New Scientist. 193 (2593): 28–32. doi:10.1016/s0262-4079(07)60550-8.

- ↑ Modern Humans, Neanderthals May Have Interbred; Humans and Neanderthals interbred Archived 2009-02-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Lagar Velho 1 Skeleton". TalkOrigins. 2000. Retrieved January 1, 2011. ; Sample, Ian (14 September 2006). "Life on the edge: was a Gibraltar cave last outpost of the lost neanderthal?". The Guardian. Retrieved January 1, 2011. ; "Not a lasting last for the Neandertals". John Hawks Weblog. September 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ↑ Soficaru A, Dobos A, Trinkaus E (November 2006). "Early modern humans from the Pestera Muierii, Baia de Fier, Romania". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (46): 17196–17201. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317196S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608443103. PMC 1859909. PMID 17085588.

- ↑ Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, et al. (May 2010). "A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–722. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMC 5100745. PMID 20448178.

- ↑ Duarte C, Maurício J, Pettitt PB, Souto P, Trinkaus E, van der Plicht H, Zilhão J (June 1999). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern-human emergence in Iberia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7604–7609. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7604D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ↑ Ruzicka J, Hansen EH, Ghose AK, Mottola HA (February 1979). "Enzymatic determination of urea in serum based on pH measurement with the flow injection method". Analytical Chemistry. 51 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1021/ac50038a011. PMID 33580.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/articles/nature14558?WT.ec_id=NATURE-20150813&spMailingID=49306476&spUserID=MjA1NTkxNTc2NAS2&spJobID=741956713&spReportId=NzQxOTU2NzEzS0

- ↑ Hayes, Jacqui (2 November 2006). "Humans and Neanderthals interbred". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ↑ Sánchez-Quinto, F; Botigué, LR; Civit, S; Arenas, C; Avila-Arcos, MC; Bustamante, CD; Comas, D; Lalueza-Fox, C (October 17, 2012). "North African Populations Carry the Signature of Admixture with Neandertals". PLoS ONE. 7 (10): e47765. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747765S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047765. PMC 3474783. PMID 23082212.

- ↑ Fu, Q; Li, H; Moorjani, P; Jay, F; Slepchenko, S. M.; Bondarev, A. A.; Johnson, P. L.; Aximu-Petri, A; Prüfer, K; De Filippo, C; Meyer, M; Zwyns, N; Salazar-García, D. C.; Kuzmin, Y. V.; Keates, S. G.; Kosintsev, P. A.; Razhev, D. I.; Richards, M. P.; Peristov, N. V.; Lachmann, M; Douka, K; Higham, T. F.; Slatkin, M; Hublin, J. J.; Reich, D; Kelso, J; Viola, T. B.; Pääbo, S (23 October 2014). "Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia". Nature. 514 (7523): 445–449. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..445F. doi:10.1038/nature13810. hdl:10550/42071. PMC 4753769. PMID 25341783.

- ↑ Brahic, Catherine. "Humanity's forgotten return to Africa revealed in DNA", The New Scientist (February 3, 2014).

- ↑ "Neanderthals mated with modern humans much earlier than previously thought, study finds: First genetic evidence of modern human DNA in a Neanderthal individual". ScienceDaily. 17 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ "The Combined Landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal Ancestry in Present-Day Humans", Current Biology, Sankararaman et al., 26, 1241–1247, 2016

- ↑ "Neanderthals may have faced extinction long before modern humans emerged". Phys.org. 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ Fisher, Richard V.; Giovanni Orsi; Michael Ort; Grant Heiken (June 1993). "Mobility of a large-volume pyroclastic flow – emplacement of the Campanian ignimbrite, Italy". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 56 (3): 205–220. Bibcode:1993JVGR...56..205F. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(93)90017-L. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ↑ Golovanova, Liubov Vitaliena; Doronichev, Vladimir Borisovich; Cleghorn, Naomi Elansia; Koulkova, Marianna Alekseevna; Sapelko, Tatiana Valentinovna; Shackley, M. Steven (2010). "Significance of Ecological Factors in the Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition". Current Anthropology. 51 (5): 655. doi:10.1086/656185.

- 1 2 3 Than, Ker (September 22, 2010). "Volcanoes Killed Off Neanderthals, Study Suggests". National Geographic. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ Gilligan, I (2007). "Neanderthal extinction and modern human behaviour: the role of climate change and clothing". World Archaeology. 39 (4): 499–514. doi:10.1080/00438240701680492.

- ↑ Climate Change Killed Neandertals, Study Says, National Geographic News

- ↑ "Volcanoes wiped out Neanderthals, new study suggests (ScienceDaily)". University of Chicago Press Journals. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ↑ Neanderthal Apocalypse Documentary film, ZDF Enterprises, 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

External links

- Hey Good Lookin': Early Humans Dug Neanderthals – audio report by NPR (6 May 2010)

_T1a.png)