Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō (南無妙法蓮華經) (also pronounced Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō)[1] (English: Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Sutra or Glory to the Sutra of the Lotus of the Supreme Law)[2][3] is the central mantra chanted within all forms of Nichiren Buddhism as well as Tendai Buddhism.[4]

The words Myōhō Renge Kyō refer to the Japanese title of the Lotus Sūtra. The mantra is referred to as daimoku (題目[5]) or, in honorific form, o-daimoku (お題目) meaning title and was first revealed by the Japanese Buddhist priest Nichiren on the 28th day of the lunar month of 1253 at Seichō-ji (also called Kiyosumi-dera) in present-day city of Kamogawa, Chiba prefecture, Japan.[6][7]

The practice of prolonged chanting is referred to as shōdai (唱題) while the purpose of chanting daimoku is to reduce sufferings by eradicating negative karma along with reducing karmic punishments both from previous and present lifetimes,[8] with the goal to attain perfect and complete awakening.[9]

Meaning

The Tendai monks Saicho and Genshin are said to have originated the Daimoku although the Buddhist priest Nichiren is known as the greatest proponent. The mantra is an homage to the Lotus Sutra which is widely credited as the "king of scriptures" and "final word on Buddhism". According to Jacqueline Stone, the Tendai founder Saicho popularized the mantra "Namu Ichijo Myoho Renge Kyo" as a way to honor the Lotus Sutra as the One Vehicle teaching of the Buddha.[10] Accordingly, the Tendai monk Genshin popularized the mantra "Namu Amida, Namu Kanzeon, Namu Myoho Renge Kyo" to honor the three jewels of Japanese Buddhism.[11] Nichiren, who himself was a Tendai monk, edited these chants down to "Namu Myoho Renge Kyo" and Nichiren Buddhists are responsible for its wide popularity and usage all over the world today.

As Nichiren explained the mantra in his Ongi Kuden,[12] a transcription of his lectures about the Lotus Sutra, Namu (南無) is a transliteration into Japanese of the Sanskrit "namas", and Myōhō Renge Kyō is the Sino-Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese title of the Lotus Sutra (hence, Daimoku, which is a Japanese word meaning 'title'), in the translation by Kumārajīva. Nichiren gives a detailed interpretation of each character (see Ongi kuden#Nam-myoho-renge-kyo) in this text. [13]

Namu is used in Buddhism as a prefix expressing taking refuge in a Buddha or similar object of veneration. In Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō, it represents devotion or conviction in the Mystic Law of Life (Saddharma) as expounded in the Lotus Sutra, not merely as one of many scriptures, but as the ultimate teaching of Buddhism, particularly with regard to Nichiren's interpretation. The use of Nam vs. Namu is, amongst traditional Nichiren schools, a linguistic but not necessarily a dogmatic issue,[14] since u is devoiced in many varieties of Japanese.[15]

Linguistically, Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō consists of the following:

- Namu 南無 "devoted to", a transliteration of Sanskrit namas

- Myōhō 妙法 "exquisite law"[16]

- Myō 妙, from Middle Chinese mièw, "strange, mystery, miracle, cleverness"

- Hō 法, from Middle Chinese pjap, "law, principle, doctrine"

- Renge-kyō 蓮華經 "Lotus Sutra"

The Lotus Sutra is held by Nichiren Buddhists, as well as practitioners of the Tiantai and corresponding Japanese Tendai schools, to be the culmination of Gautama Buddha's 50 years of teaching. However, followers of Nichiren Buddhism consider Myōhō Renge Kyō to be the name of the ultimate law permeating the universe, and the human being is at one, fundamentally with this law (dharma) and can manifest realization, or Buddha Wisdom (attain Buddhahood), through Buddhist Practice.

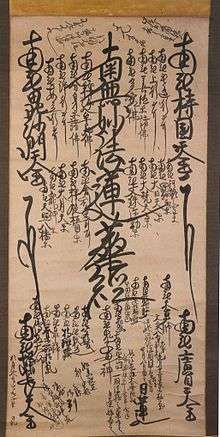

The seven characters of the phrase are written down the centre of the gohonzon, the mandala venerated by most Nichiren Buddhists. The veneration towards the mandala is understood by those who believe in it as the veneration for a deeper representation, which they believe to be the Buddha Nature inherent to their own lives.

More recently, with the participation of the Nichiren Buddhist order Nipponzan Myohoji in the peace movement, the mantra has become a more universally recognized prayer for peace. On peace walks it is chanted whilst beating Japanese hand drums, in a practice known as gyakku-Shodai.

In popular culture

This mantra has been associated with influential figures including Mahatma Gandhi and Rosa Parks and has been popularized due to the Peace Stupas built all over India.[17]

Perhaps the most famous and well-known attribution in pop culture is in Tina Turner's autobiographical movie What's Love Got To Do With It, featuring her conversion to Nichiren Buddhism in the early 1970s through her co-dancer friend Jackie Stanton. In the film, after an attempted suicide, Tina Turner begins to chant this mantra and turns her life around. Turner continues to chant this mantra in public venues such as CNN and in her own spiritual music project Beyond.[18]

The mantra was used in the final episode of The Monkees to break Peter out of a trance.

The mantra is also present in the 1969 movie Satyricon by Federico Fellini during the grand nude jumping scene of the Patricians.

The mantra is used by the underdog fraternity in the film Revenge of the Nerds II in the fake Seminole temple against the Alpha Betas.

In the film Innerspace, Tuck Pendleton (played by Dennis Quaid) chants this mantra repeatedly as he encourages Jack Putter to break free from his captors and charge the door of the van he is being held in.

The mantra has been used in contemporary popular culture and appears in songs such as The Pretenders' "Boots of Chinese Plastic"[19] and Xzibit's "Concentrate".

Notes

- ↑ Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia - Five or seven characters

- ↑ SGDB 2002, Lotus Sutra of the Wonderful Law

- ↑ Kenkyusha 1991

- ↑ https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/4327

- ↑ Kenkyusha 1991

- ↑ Anesaki 1916, p.34

- ↑ SGDB 2002, Nichiren

- ↑ http://myohoji.nst.org/NSTMyohoji.aspx?PI=BOP.5550

- ↑ http://www.sgi.org/about-us/buddhism-in-daily-life/changing-poison-into-medicine.html

- ↑ Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism by Jacqueline Stone

- ↑ Re-envisioning Kamakura Buddhism by Richard Payne

- ↑ Watson 2005

- ↑ Masatoshi, Ueki (2001). Gender equality in Buddhism. Peter Lang. pp. 136, 159–161. ISBN 0820451339.

- ↑ Ryuei 1999, Nam or Namu? Does it really matter?

- ↑ P. M, Suzuki (2011). The Phonetics of Japanese Language: With Reference to Japanese Script. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 0415594138.

- ↑ Kenkyusha 1991

- ↑ http://www.livemint.com/Consumer/BZ7pk5BYrdnijntpLDgdbN/Exhibition-of-8216Lotus-Sutra8217-in-the-capital.html

- ↑ https://tinaturnerblog.com/tag/nam-myoho-renge-kyo/

- ↑ "Pretenders - Boots Of Chinese Plastic Lyrics". Metrolyrics.com. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

References

- Anesaki, Masaharu (1916). Nichiren, the Buddhist prophet. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Kenkyusha (1991). Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary. Tokyo: Kenkyusha Limited. ISBN 4-7674-2015-6.

- Ryuei, Rev. (1999). "Lotus Sutra Commentaries". Nichiren's Coffeehouse. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- SGDB (2002). "The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism". Soka Gakkai International. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- Watson, Burton (2005). The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings (trans.). Soka Gakkai. ISBN 4-412-01286-7.

Further reading

- Causton, Richard: The Buddha in Daily Life, An Introduction of Nichiren Buddhism, Rider London 1995; ISBN 978-0712674560

- Hochswender, Woody: The Buddha in Your Mirror: Practical Buddhism and the Search for Self, Middleway Press 2001; ISBN 978-0967469782

- Montgomery, Daniel B.: Fire In The Lotus, The Dynamic Buddhism of Nichiren, Mandala 1991; ISBN 1-85274-091-4

- Payne, Richard, K. (ed.): Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press Honolulu 1998; ISBN 0-8248-2078-9

- Stone, Jacqueline, I.: "Chanting the August Title of the Lotus Sutra: Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan". In: Payne, Richard, K. (ed.); Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1998, pp. 116–166. ISBN 0-8248-2078-9