Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II

| F-35 Lightning II | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| F-35A Lightning II | |

| Role | Stealth multirole fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin Aeronautics |

| First flight | 15 December 2006 (F-35A) |

| Introduction | F-35B: 31 July 2015 (USMC)[1][2][3] F-35A: 2 August 2016 (USAF)[4] F-35C: 2018, planned (USN)[5] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force United States Marine Corps United States Navy See Operators section for others |

| Produced | 2006–present |

| Number built | 320+ as of 11 September 2018[6] |

| Program cost | US$1.508 trillion (through 2070 in then-year dollars), US$55.1B for RDT&E, $319.1B for procurement, $4.8B for MILCON, $1123.8B for operations & sustainment (2015 estimate)[7] |

| Unit cost |

F-35A: $89.2M (low rate initial production lot 11 (LRIP 11) including F135 engine, cost in 2020 to be $80M)[8] F-35B: US$115.5M (LRIP 11 including engine)[8] F-35C: US$107.7M (LRIP 11 including engine)[8] |

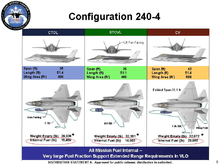

| Developed from | Lockheed Martin X-35 |

The Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II is a family of single-seat, single-engined, all-weather stealth multirole fighters. The fifth-generation combat aircraft is designed to perform ground-attack and air-superiority missions. It has three main models: the F-35A conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL) variant, the F-35B short take-off and vertical-landing (STOVL) variant, and the F-35C carrier-based catapult-assisted take-off but arrested recovery (CATOBAR) variant. On 31 July 2015, the United States Marines declared ready for deployment the first squadron of F-35B fighters after intensive testing.[9][10] On 2 August 2016, the U.S. Air Force declared its first squadron of F-35A fighters combat-ready.[11]

The F-35 descends from the X-35, the winning design of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program. An aerospace industry team led by Lockheed Martin designed and manufactures it. Other major F-35 industry partners include Northrop Grumman, Pratt & Whitney, Raytheon Company and BAE Systems. The F-35 first flew on 15 December 2006. The United States plans to buy 2,663 aircraft. Its variants are to provide the bulk of the crewed tactical airpower of the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps over the coming decades. Deliveries of the F-35 for the U.S. military are scheduled until 2037[12] with a projected service life up to 2070.[13]

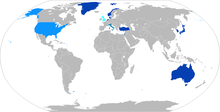

The United States principally funds the F-35 JSF development, with additional funding from partners. The partner nations are either NATO members or close U.S. allies. The United Kingdom, Italy, Australia, Canada, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Turkey are part of the active development program;[14][15] several additional countries have ordered, or are considering ordering, the F-35. Turkey, as an industrial partner, is the sole source supplier for several parts used in the F-35: Vice Admiral Mat Winter, F-35 programme director, told Janes reporters on 1 October 2018 that Turkey's industrial base "provides multiple parts on every F-35", including US F-35s.[16][17]

As the largest and most expensive military program, the F-35 is the subject of much scrutiny and criticism in the U.S. and in other countries.[18] In 2013 and 2014, critics argued that the plane was "plagued with design flaws", with many blaming the procurement process in which Lockheed was allowed "to design, test, and produce the F-35 all at the same time, instead of… [identifying and fixing] defects before firing up its production line".[18] By 2014, the program was "$163 billion over budget [and] seven years behind schedule".[19] Critics also contend that the program's high sunk costs and political momentum make it "too big to kill".[20]

In 2018, the F-35 was used in combat for the first time,[21] as the Israeli Air Force's F-35I became operational, had been flown "all over the Middle East",[22] and had carried out the plane's first combat airstrikes in the world on two different battlefronts.[22]

Development

F-35 development started in 1992 with the origins of the Joint Strike Fighter program and is to culminate in full production in 2018.[23] The X-35 first flew on 24 October 2000 and the F-35A on 15 December 2006. The F-35 was developed to replace most US fighter jets with variants of one design common to all branches of the military. It was developed in co-operation with a number of foreign partners, and unlike the F-22 Raptor, intended to be available for export. Three variants were designed: the F-35A (CTOL), the F-35B (STOVL), and the F-35C (CATOBAR). Despite being intended to share most of their parts to reduce costs and improve maintenance logistics, by 2017, the design commonality was only 20%.[24] The program received considerable criticism for cost overruns during development and for the total projected cost of the program over the lifetime of the jets. By 2017, the program was expected over its lifetime (until 2070) to cost $406.5 billion for acquisition of the jets and $1.1 trillion for operations and maintenance.[25] A number of design deficiencies were alleged, such as carrying a small internal payload, inferior performance to the aircraft being replaced, particularly the F-16, and the lack of safety in relying on a single engine, and flaws were noted such as vulnerability of the fuel tank to fire and the propensity for transonic roll-off (wing drop). The possible obsolescence of stealth technology was also criticized.

Design

Overview

The single-engined F-35 closely resembles the larger twin-engined Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor, drawing design elements from its sibling. The exhaust duct design was inspired by the General Dynamics Model 200, proposed for a 1972 supersonic VTOL fighter requirement for the Sea Control Ship.[26] Although several experimental designs have been developed since the 1960s, such as the unsuccessful Rockwell XFV-12, the F-35B is to be the first operational supersonic STOVL stealth fighter.[27]

Acquisition deputy to the assistant secretary of the Air Force, Lt. Gen. Mark D. "Shack" Shackelford, has said that the F-35 is designed to be America's "premier surface-to-air missile killer and is uniquely equipped for this mission with cutting edge processing power, synthetic aperture radar integration techniques, and advanced target recognition".[28][29] Lockheed Martin states the F-35 is intended to have close- and long-range air-to-air capability second only to that of the F-22 Raptor.[30] Lockheed Martin has said that the F-35 has the advantage over the F-22 in basing flexibility and "advanced sensors and information fusion".[31] Lockheed Martin has suggested that the F-35 could replace the USAF's F-15C/D fighters in the air superiority role and the F-15E Strike Eagle in the ground attack role.[32]

Some improvements over current-generation fighter aircraft include:

- Durable, low-maintenance stealth technology, using structural fiber mat instead of the high-maintenance coatings of legacy stealth platforms.[33]

- Integrated avionics and sensor fusion that combine information from off- and on-board sensors to increase the pilot's situational awareness and improve target identification and weapon delivery, and to relay information quickly to other command and control (C2) nodes.[34][35][36]

- High speed data networking including IEEE 1394b[37] and Fibre Channel.[38] (Fibre Channel is also used on Boeing's Super Hornet.[39])

- The Autonomic Logistics Global Sustainment (ALGS), Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), and Computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) are to help ensure the aircraft can remain operational with minimal maintenance manpower.[40] The Pentagon has moved to open up the competitive bidding by other companies.[41] This was after Lockheed Martin stated that instead of costing twenty percent less than the F-16 per flight hour, the F-35 would actually cost twelve percent more.[42] Though the ALGS is intended to reduce maintenance costs, the company disagrees with including the cost of this system in the aircraft ownership calculations.[43] The USMC have implemented a workaround for a cyber vulnerability in the system.[44] The ALIS system currently requires a shipping container load of servers to run, but Lockheed is working on a more portable version to support the Marines' expeditionary operations.[45]

- Electro-hydrostatic actuators run by a power-by-wire flight-control system.[46]

- A modern and updated flight simulator, which may be used for a greater fraction of pilot training in order to reduce the costly flight hours of the actual aircraft.[47]

- Lightweight, powerful lithium-ion batteries to provide power to run the control surfaces in an emergency.[48]

Structural composites in the F-35 are 35% of the airframe weight (up from 25% in the F-22).[49] The majority of these are bismaleimide (BMI) and composite epoxy material.[50] The F-35 will be the first mass-produced aircraft to include structural nanocomposites, namely carbon nanotube-reinforced epoxy.[51] Experience of the F-22's problems with corrosion led to the F-35 using a gap filler that causes less galvanic corrosion to the airframe's skin, designed with fewer gaps requiring filler and implementing better drainage.[52] The relatively short 35-foot wingspan of the A and B variants is set by the F-35B's requirement to fit inside the Navy's current amphibious assault ship parking area[53] and elevators; the F-35C's longer wing is considered to be more fuel efficient.[54]

A United States Navy study found that the F-35 will cost 30 to 40 percent more to maintain than current jet fighters,[55] not accounting for inflation over the F-35's operational lifetime. A Pentagon study concluded a $1 trillion maintenance cost for the entire fleet over its lifespan, not accounting for inflation.[56] The F-35 program office found that as of January 2014, costs for the F-35 fleet over a 53-year life cycle was $857 billion. Costs for the fighter have been dropping and accounted for the 22 percent life cycle drop since 2010.[57] Lockheed stated that by 2019, pricing for the fifth-generation aircraft will be less than fourth-generation fighters. An F-35A in 2019 is expected to cost $85 million per unit complete with engines and full mission systems, inflation adjusted from $75 million in December 2013.[58]

Engines

The Pratt & Whitney F135 powers the F-35. An alternative engine, the General Electric/Rolls-Royce F136, was being developed until it was cancelled by its manufacturers in December 2011 for lack of funding from the Pentagon.[59][60] The F135 and F136 engines are not designed to supercruise.[61] However, the F-35 can briefly fly at Mach 1.2 for 150 miles without the use of an afterburner.[62] The F135 is the second (radar) stealthy afterburning jet engine. Like the Pratt & Whitney F119 from which it was derived, the F135 has suffered afterburner pressure pulsations, or 'screech' at low altitude and high speed.[63] The F-35 has a maximum speed of over Mach 1.6. With a maximum takeoff weight of 60,000 lb (27,000 kg),[lower-alpha 1][65] the Lightning II is considerably heavier than the lightweight fighters it replaces.

The STOVL F-35B is outfitted with the Rolls-Royce LiftSystem, designed by Lockheed Martin and developed by Rolls-Royce. This system more resembles the German VJ 101D/E than the preceding STOVL Harrier Jump Jet and the Rolls-Royce Pegasus engine.[66][67][68] The Lift System is composed of a lift fan, drive shaft, two roll posts and a "Three Bearing Swivel Module" (3BSM).[69] The 3BSM is a thrust vectoring nozzle which allows the main engine exhaust to be deflected downward at the tail of the aircraft. The lift fan is near the front of the aircraft and provides a counterbalancing thrust using two counter-rotating blisks.[70] It is powered by the engine's low-pressure (LP) turbine via a drive shaft and gearbox. Roll control during slow flight is achieved by diverting unheated engine bypass air through wing-mounted thrust nozzles called Roll Posts.[71][72]

F136 funding came at the expense of other program elements, impacting on unit costs.[73] The F136 team stated their engine had a greater temperature margin, potentially critical for VTOL operations in hot, high altitude conditions.[74] Pratt & Whitney tested higher thrust versions of the F135, partly in response to GE's statements that the F136 is capable of producing more thrust than the 43,000 lbf (190 kN) of early F135s. In testing, the F135 has demonstrated a maximum thrust of over 50,000 lbf (220 kN);[75] making it the most powerful engine ever installed in a fighter aircraft as of 2010.[76] It is much heavier than previous fighter engines; the Heavy Underway Replenishment system needed to transfer the F135 between ships is an unfunded USN requirement.[77] Thermoelectric-powered sensors monitor turbine bearing health.[78] At the end of May 2017 Pratt and Whitney announced the F135 Growth Option 1 had finished testing and was available for production. The upgrade requires the changing of the power module on older engines and can be seamlessly inserted into future production engines at a minimal increase in unit cost and no impact to delivery schedule. The Growth Option 1 offers a improvement of 6–10% thrust across the F-35 flight envelope while also getting a 5–6% fuel burn reduction.[79]

Armament

The F-35A is armed with a GAU-22/A, a four-barrel version of the 25 mm GAU-12 Equalizer cannon.[80] The cannon is mounted internally with 182 rounds for the F-35A or in an external pod with 220 rounds for the F-35B and F-35C;[81][82] the gun pod has stealth features.[83] Software updates to enable operational firing of the cannon are expected to be completed by 2018.[84] The F-35 has two internal weapons bays, and external hardpoints for mounting up to four underwing pylons and two near wingtip pylons. The two outer hardpoints can carry pylons for the AIM-9X Sidewinder and AIM-132 ASRAAM short-range air-to-air missiles (AAM) only.[85] The other pylons can carry the AIM-120 AMRAAM BVR AAM, AGM-158 Joint Air to Surface Stand-off Missile (JASSM) cruise missile, and guided bombs. The external pylons can carry missiles, bombs, and external fuel tanks at the expense of increased radar cross-section, and thus reduced stealth.[86]

There are a total of four weapons stations between the two internal bays. Two of these can carry air-to-surface missiles or bombs up to 2,000 lb (910 kg) each in the A and C models, or air-to-surface missiles or bombs up to 1,000 lb (450 kg) each in the B model; the other two stations are for smaller weapons such as air-to-air missiles.[87][88] The weapon bays can carry AIM-120 AMRAAM, AIM-132 ASRAAM, the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM), Paveway series of bombs, the Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW), Brimstone anti-tank missiles, and cluster munitions (Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser).[87] An air-to-air missile load of eight AIM-120s and two AIM-9s is possible using internal and external weapons stations; a configuration of six 2,000 lb (910 kg) bombs, two AIM-120s and two AIM-9s can also be arranged.[87][89] The Terma A/S multi-mission pod (MMP) could be used for different equipment and purposes, such as electronic warfare, aerial reconnaissance, or rear-facing tactical radar.[83][90] The British Ministry of Defence plan to fire the Select Precision Effects at Range (SPEAR) Capability 3 missile from the internal bays of the F-35B, with four missiles per bay.[91][92]

Lockheed Martin states that the weapons load can be configured as all-air-to-ground or all-air-to-air, and has suggested that a Block 5 version will carry three weapons per bay instead of two, replacing the heavy bomb with two smaller weapons such as AIM-120 AMRAAM air-to-air missiles.[93] Upgrades are to allow each weapons bay to carry four GBU-39 Small Diameter Bombs (SDB) for A and C models, or three in F-35B.[94] Another option is four GBU-53/B Small Diameter Bomb IIs in each bay on all F-35 variants.[95] The F-35A has been outfitted with four SDB II bombs and an AMRAAM missile to test adequate bay door clearance,[96] as well as the C-model, but the STOVL F-35B will not be able to carry the required load of four SDB IIs in each weapons bay upon reaching IOC because of weight and dimension constraints; F-35B bay changes are to be incorporated to increase SDB II loadout around 2022 in line with the Block 4 weapons suite.[97] The Meteor air-to-air missile may be adapted for the F-35, a modified Meteor with smaller tailfins for the F-35 was revealed in September 2010; plans call for the carriage of four Meteors internally.[98] The United Kingdom planned to use up to four AIM-132 ASRAAM missiles internally, later plans call for the carriage of two internal and two external ASRAAMs.[99] The external ASRAAMs are planned to be carried on "stealthy" pylons; the missile allows attacks to slightly beyond visual range without employing radar.[85][100]

Norway and Australia are funding an adaptation of the Naval Strike Missile (NSM) for the F-35. Under the designation Joint Strike Missile (JSM), it is to be the only cruise missile to fit the F-35's internal bays; according to studies two JSMs can be carried internally with an additional four externally.[101] The F-35 is expected to take on the Wild Weasel mission, though there are no planned anti-radiation missiles for internal carriage.[102] In September 2016, Orbital ATK unveiled its extended-range AARGM-ER incorporating a redesigned control section and 11.5 in (290 mm)-diameter rocket motor for twice the range for internal carriage on the F-35. The B61 nuclear bomb was initially scheduled for deployment in 2017;[103] as of 2012 it was expected to be in the early 2020s,[104] and in 2014 Congress moved to cut funding for the needed weapons integration work.[105] Norton A. Schwartz agreed with the move and said that "F-35 investment dollars should realign to the long-range strike bomber".[106] NATO partners who are buying the F-35 but cannot afford to make them dual-capable want the USAF to fund the conversions to allow their Lightning IIs to carry thermonuclear weapons. The USAF is trying to convince NATO partners who can afford the conversions to contribute to funding for those that cannot. The F-35 Block 4B will be able to carry two B61 nuclear bombs internally by 2024.[107]

According to reports in 2002, solid-state lasers were being developed as optional weapons for the F-35.[108][109][110] Lockheed is studying integrating a fiber laser onto the aircraft that uses spectral beam combining to channel energy from a stack of individual laser modules into a single, high-power beam, which can be scaled up or down for various levels of effects. Adding a laser would give the F-35 the ability to essentially burn missiles and other aircraft out of the sky.[111] The F-35 is also one of the target platforms for the High Speed Strike Weapon if hypersonic missile development is successful.[112]

The Air Force plans to use the F-35A to primarily take up the close air support (CAS) mission in contested environments. Amid criticism that the aircraft is not well suited for the role compared to a dedicated attack platform, Air Force chief of staff Mark Welsh is putting focus on weapons for the F-35 to employ on CAS sorties including guided rockets, fragmentation rockets that would shatter into individual projectiles before impact, and lighter, smaller ammunition in higher capacity gun pods.[113] Fragmentary rocket warheads would have greater effects than cannon shells fired from a gun because a single rocket would create a "thousand-round burst", delivering more projectiles than a strafing run could. Other weapons could take advantage of the aircraft's helmet-mounted cueing system to aim rather than needing to point the nose at a target.[114] Institute for the Study of War's Christopher Harmer has questioned the use of such an expensive aircraft for CAS.[115]

Stealth and signatures

Radar

The F-35 has been designed to have a low radar cross-section that is primarily due to the shape of the aircraft and the use of stealthy, radar-absorbent materials in its construction, including fiber-mat.[33] Unlike the previous generation of fighters, the F-35 was designed for very-low-observable characteristics.[116] Besides radar stealth measures, the F-35 incorporates infrared signature and visual signature reduction measures.[117][118]

The Fighter Teen Series (F-14, F-15, F-16, F/A-18) carried large external fuel tanks, but to avoid negating its stealth characteristics the F-35 must fly most missions without them. Unlike the F-16 and F/A-18, the F-35 lacks leading edge extensions and instead uses stealth-friendly chines for vortex lift in the same fashion as the SR-71 Blackbird.[90] The small bumps just forward of the engine air intakes form part of the diverterless supersonic inlet (DSI) which is a simpler, lighter means to ensure high-quality airflow to the engine over a wide range of conditions. These inlets also crucially improve the aircraft's very-low-observable characteristics (by eliminating radar reflections between the diverter and the aircraft's skin).[119] Additionally, the "bump" surface reduces the engine's exposure to radar, significantly reducing a strong source of radar reflection[120] because they provide an additional shielding of engine fans against radar waves. The Y-duct type air intake ramps also help in reducing radar cross-section (RCS), because the intakes run parallel and not directly into the engine fans.

The F-35's radar-absorbent materials are designed to be more durable and less maintenance-intensive than those of its predecessors. At optimal frequencies, the F-35 compares favorably to the F-22 in stealth, according to General Mike Hostage, Commander of the Air Combat Command.[121][122] Like other stealth fighters, however, the F-35 is more susceptible to detection by low-frequency radars because of the Rayleigh scattering resulting from the aircraft's physical size. However, such radars are also conspicuous, susceptible to clutter, and have low precision.[123][124] Although fighter-sized stealth aircraft could be detected by low-frequency radar, missile lock and targeting sensors primarily operate in the X-band, which F-35 RCS reduction is made for, so they cannot engage unless at close range.[125] Because the aircraft's shape is important to the RCS, special care must be taken to match the "boilerplate" during production.[126] Ground crews require Repair Verification Radar (RVR) test sets to verify the RCS after performing repairs, which is not a concern for non-stealth aircraft.[127][128]

Acoustics

In 2008, the Air Force revealed that the F-35 would be about twice as loud as the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle at takeoff and up to four times as loud during landing.[129] Residents near Luke Air Force Base, Arizona, and Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, possible F-35 bases, requested environmental impact studies be conducted regarding the F-35's noise levels.[129] In 2009, the city of Valparaiso, Florida, adjacent to Eglin AFB, threatened to sue over the impending F-35 arrival; this lawsuit was settled in March 2010.[130][131][132] In 2009, testing reportedly revealed the F-35 to be: "only about as noisy as an F-16 fitted with a Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-200 engine ... quieter than the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor and the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet".[133] An acoustics study by Lockheed Martin and the Air Force found F-35's noise levels to be comparable to the F-22 and F/A-18E/F.[134] A USAF environmental impact study found that replacing F-16s with F-35s at Tucson International Airport would subject more than 21 times as many residents to extreme noise levels.[135] The USN will need to redesign hearing protection for sailors to protect against the "thundering 152 decibels" of the F-35.[136] The Joint Strike Fighter program office found in October 2014 that the F-35B's take-off noise was only two decibels higher than a Super Hornet, a virtually indistinguishable difference to the human ear, and is even 10 decibels quieter when flying formations or landing.[137]

Cockpit

The F-35 features a full-panel-width glass cockpit touchscreen[138] "panoramic cockpit display" (PCD), with dimensions of 20 by 8 inches (50 by 20 centimeters).[139] A cockpit speech-recognition system (DVI) provided by Adacel has been adopted on the F-35 and the aircraft will be the first operational U.S. fixed-wing aircraft to employ this DVI system, although similar systems have been used on the AV-8B Harrier II and trialed in previous aircraft, such as the F-16 VISTA.[140]

A helmet-mounted display system (HMDS) will be fitted to all models of the F-35.[141] While some fighters have offered HMDS along with a head up display (HUD), this will be the first time in several decades that a front line fighter has been designed without a HUD.[142] The F-35 is equipped with a right-hand HOTAS side stick controller. The Martin-Baker US16E ejection seat is used in all F-35 variants.[143] The US16E seat design balances major performance requirements, including safe-terrain-clearance limits, pilot-load limits, and pilot size; it uses a twin-catapult system housed in side rails.[144] This industry standard ejection seat can cause the heavier than usual helmet to inflict serious injury on lightweight pilots.[145]

The F-35 employs an oxygen system derived from the F-22's own system, which has been involved in multiple hypoxia incidents on that aircraft; unlike the F-22, the flight profile of the F-35 is similar to other fighters that routinely use such systems.[146][147] On June 9, 2017, the 55 F-35s at Luke Air Force Base were grounded after five pilots complained of hypoxia-like symptoms over a five-week span. Symptoms ranged from dizziness to tingling in their extremities. The suspension was initially expected to last one day, but was extended to give investigators more time. Flying was resumed on 20 June, with no direct cause having been found.[148]

Sensors and avionics

The F-35's sensor and communications suite has situational awareness, command and control and network-centric warfare capabilities.[30][149] The main sensor on board is the AN/APG-81 active electronically scanned array-radar, designed by Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems.[150] It is augmented by the nose-mounted Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS),[151] it provides the capabilities of an externally mounted Sniper Advanced Targeting Pod with a reduced radar cross-section.[152][153] The AN/ASQ-239 (Barracuda) system is an improved version of the F-22's AN/ALR-94 electronic warfare suite, providing sensor fusion of radio frequency and infrared tracking functions, advanced radar warning receiver including geolocation targeting of threats, multispectral image countermeasures for self-defense against missiles, situational awareness and electronic surveillance, employing 10 radio frequency antennae embedded into the edges of the wing and tail.[154][155] In September 2015, Lockheed unveiled the "Advanced EOTS" that offers short-wave infrared, high-definition television, infrared marker, and superior image detector resolution capabilities. Offered for the Block 4 configuration, it fits into the same area as the baseline EOTS with minimal changes while preserving stealth features.[156]

Six additional passive infrared sensors are distributed over the aircraft as part of Northrop Grumman's electro-optical AN/AAQ-37 Distributed Aperture System (DAS),[157] which acts as a missile warning system, reports missile launch locations, detects and tracks approaching aircraft spherically around the F-35, and replaces traditional night vision devices. All DAS functions are performed simultaneously, in every direction, at all times. The electronic warfare systems are designed by BAE Systems and include Northrop Grumman components.[158] Functions such as the Electro-Optical Targeting System and the electronic warfare system are not usually integrated on fighters.[159] The F-35's DAS is so sensitive, it reportedly detected the launch of an air-to-air missile in a training exercise from 1,200 mi (1,900 km) away, which in combat would give away the location of an enemy aircraft even if it had a very low radar cross-section.[160]

On 13 June 2018 it was announced Raytheon would begin developing a Next Generation DAS system for the F-35. [161]

The communications, navigation and identification (CNI) suite is designed by Northrop Grumman and includes the Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL), as one of a half dozen different physical links.[162] The F-35 will be the first fighter with sensor fusion that combines radio frequency and IR tracking for continuous all-direction target detection and identification which is shared via MADL to other platforms without compromising low observability.[64] Link 16 is also included for communication with legacy systems.[163] The F-35 has been designed with synergy between sensors as a specific requirement, the aircraft's "senses" being expected to provide a more cohesive picture of the battlespace around it and be available for use in any possible way and combination with one another; for example, the AN/APG-81 multi-mode radar also acts as a part of the electronic warfare system.[164] The Program Executive Officer (PEO) General Bogdan has described the sensor fusion software as one of the most difficult parts of the program.[165]

Much of the F-35's software is written in C and C++ because of programmer availability; Ada83 code also is reused from the F-22.[166] The Integrity DO-178B real-time operating system (RTOS) from Green Hills Software runs on COTS Freescale PowerPC processors.[167] The final Block 3 software is planned to have 8.6 million lines of code.[168] In 2010, Pentagon officials discovered that additional software may be needed.[169] General Norton Schwartz has said that the software is the biggest factor that might delay the USAF's initial operational capability.[170] In 2011, Michael Gilmore, Director of Operational Test & Evaluation, wrote that, "the F-35 mission systems software development and test is tending towards familiar historical patterns of extended development, discovery in flight test, and deferrals to later increments".[171]

The electronic warfare and electro-optical systems are intended to detect and scan aircraft, allowing engagement or evasion of a hostile aircraft prior to being detected.[164] The CATbird avionics testbed aircraft has proved capable of detecting and jamming radars, including the F-22's AN/APG-77.[172] The F-35 was previously considered a platform for the Next Generation Jammer; attention shifted to using unmanned aircraft in this capacity instead.[173] Several subsystems use Xilinx FPGAs;[174] these COTS components enable supply refreshes from the commercial sector and fleet software upgrades for the software-defined radio systems.[167]

Lockheed Martin's Dave Scott stated that sensor fusion boosts engine thrust and oil efficiency, increasing the aircraft's range.[175] Air Force official Ellen M. Pawlikowski has proposed using the F-35 to control and coordinate multiple unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs). Using its sensors and communications equipment, a single F-35 could orchestrate an attack made by up to 20 armed UCAVs.[176]

Helmet-mounted display system

The F-35 does not need to be physically pointing at its target for weapons to be successful.[87][177] Sensors can track and target a nearby aircraft from any orientation, provide the information to the pilot through their helmet (and therefore visible no matter which way the pilot is looking), and provide the seeker-head of a missile with sufficient information. Recent missile types provide a much greater ability to pursue a target regardless of the launch orientation, called "High Off-Boresight" capability. Sensors use combined radio frequency and infra red (SAIRST) to continually track nearby aircraft while the pilot's helmet-mounted display system (HMDS) displays and selects targets; the helmet system replaces the display-suite-mounted head-up display used in earlier fighters.[178] Each helmet costs $400,000.[179]

The F-35's systems provide the edge in the "observe, orient, decide, and act" OODA loop; stealth and advanced sensors aid in observation (while being difficult to observe), automated target tracking helps in orientation, sensor fusion simplifies decision making, and the aircraft's controls allow the pilot to keep their focus on the targets, rather than the controls of their aircraft.[180][lower-alpha 2]

Problems with the Vision Systems International helmet-mounted display led Lockheed Martin-Elbit Systems to issue a draft specification for alternative proposals in early 2011, to be based around the Anvis-9 night vision goggles.[181] BAE Systems was selected to provide the alternative system in late 2011.[182] The BAE Systems alternative helmet was to include all the features of the VSI system.[183] However, adopting the alternative helmet would have required a cockpit redesign,[184] but in 2013 development on the alternative helmet was halted because of progress on the baseline helmet.[185]

In 2011, Lockheed Martin-Elbit granted VSI a contract to fix the vibration, jitter, night-vision and sensor display problems in their helmet-mounted display.[186] A speculated potential improvement is the replacement of Intevac’s ISIE-10 day/night camera with the newer ISIE-11 model.[187] In October 2012, Lockheed Martin-Elbit stated that progress had been made in resolving the technical issues of the helmet-mounted display, and cited positive reports from night flying tests; it had been questioned whether the helmet system allows pilots enough visibility at night to carry out precision tasks.[188] In 2013, in spite of continuing problems with the helmet display, the F-35B model completed 19 nighttime vertical landings on board the USS Wasp at sea,[189] by using the DAS instead of the helmet's built-in night vision capabilities, which offer at best 20/35 vision.[190]

In October 2013, development of the alternate helmet was halted. The current Gen 2 helmet is expected to meet the requirements to declare, in July 2015, that the F-35 has obtained initial operational capability. Beginning in 2016 with low rate initial production (LRIP) lot 7, the program will introduce a Gen 3 helmet that features an improved night vision camera, new liquid crystal displays, automated alignment and other software enhancements.[185]

In July 2015, an F-35 pilot commented that the helmet may have been one of the issues that the F-35 faced while dogfighting against an F-16 during a test; "The helmet was too large for the space inside the canopy to adequately see behind the aircraft. There were multiple occasions when the bandit would've been visible (not blocked by the seat) but the helmet prevented getting in a position to see him (behind the high side of the seat, around the inside of the seat, or high near the lift vector)".[191]

Maintenance

The program's maintenance concept is for any F-35 to be maintained in any F-35 maintenance facility and that all F-35 parts in all bases will be globally tracked and shared as needed.[192] The commonality between the different variants has allowed the USMC to create their first aircraft maintenance Field Training Detachment to directly apply the lessons of the USAF to their F-35 maintenance operations.[193] The aircraft has been designed for ease of maintenance, with 95% of all field replaceable parts "one deep" where nothing else has to be removed to get to the part in question. For instance the ejection seat can be replaced without removing the canopy, the use of low-maintenance electro-hydrostatic actuators instead of hydraulic systems and an all-composite skin without the fragile coatings found on earlier stealth aircraft.[194]

The F-35 Joint Program Office has stated that the aircraft has received good reviews from pilots and maintainers, suggesting it is performing better than its predecessors did at a similar stage of development, and that the stealth type has proved relatively stable from a maintenance standpoint. This reported improvement is attributed to better maintenance training, as F-35 maintainers have received far more extensive instruction at this early stage of the program than on the F-22 Raptor. The F-35's stealth coatings are much easier to work with than those used on the Raptor. Cure times for coating repairs are lower and many of the fasteners and access panels are not coated, further reducing the workload for maintenance crews. Some of the F-35's radar-absorbent materials are baked into the jet's composite skin, which means its stealthy signature is not easily degraded.[195] It is still harder to maintain (because of the need to preserve its stealth characteristics) than fourth-generation aircraft.[196]

However, the DOT&E Report on the F-35 program published in January 2015 determined that the plane has not, in fact, reached any of the nine reliability measures the program was supposed to achieve by this point in its development and that the Joint Program Office has been re-categorizing failure incidents to make the plane look more reliable than it actually is. Further, the complexity of maintaining the F-35 means that, currently, none of the Services are ready to keep it in working order and instead "rely heavily on contractor support and unacceptable workarounds". DOT&E found that the program achieved 61 percent of planned flight hours and that the average rate of availability was as low as 28 percent for the F-35A and 33 percent for the F-35B. The program created a new "modeled achievable" flight hour projection "since low availability was preventing the full use of bed-down plan flight hours". According to the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Financial Management, in FY2014, each non-test F-35 flew only 7.7 hours per month, which amounts to approximately one sortie every 5.5 days—for combat purposes, a sortie rate so low as to be crippling. Mean flight hours between removal (MFHBR) have increased, but are still only 59 percent to 65 percent of the required threshold. DOT&E found that mean corrective maintenance time for critical failures got worse for the F-35A and the F-35C over the last year. Structural cracking is also proving to be a recurring and enduring problem that is not yet resolved.[197]

Operational history

Testing

The first F-35A (designated AA-1) was rolled out in Fort Worth, Texas, on 19 February 2006. In September 2006, the first engine run of the F135 in an airframe took place.[198] On 15 December 2006, the F-35A completed its maiden flight.[199] A modified Boeing 737–300, the Lockheed Martin CATBird has been used as an avionics test-bed for the F-35 program, including a duplication of the cockpit.[93]

The first F-35B (designated BF-1) made its maiden flight on 11 June 2008, piloted by BAE Systems' test pilot Graham Tomlinson. Flight testing of the STOVL propulsion system began on 7 January 2010.[200] The F-35B's first hover was on 17 March 2010, followed by its first vertical landing the next day.[201] During a test flight on 10 June 2010, the F-35B STOVL aircraft achieved supersonic speeds[202] as had the X-35B before.[203] In January 2011, Lockheed Martin reported that a solution had been found for the cracking of an aluminum bulkhead during ground testing of the F-35B.[204] In 2013, the F-35B suffered another bulkhead cracking incident.[205] This will require redesign of the aircraft, which is already very close to the ultimate weight limit.[206]

| F-35B tests on USS Wasp in 2011 | |

|

| |

|

|

By June 2009, many of the initial flight test targets had been accomplished but the program was behind schedule.[207] During 2008, a Pentagon Joint Estimate Team (JET) estimated that the program was two years behind the public schedule, a revised estimate in 2009 predicted a 30-month delay.[208] Delays reduced planned production numbers by 122 aircraft through 2015 to provide an additional $2.8 billion for development; internal memos suggested that the official timeline would be extended by 13 months.[208][209] The success of the JET led Ashton Carter calling for more such teams for other poorly performing projects.[210]

Nearly 30 percent of test flights required more than routine maintenance to make the aircraft flightworthy again.[211] As of March 2010, the F-35 program had used a million more man-hours than predicted.[212] The United States Navy projected that lifecycle costs over a 65-year fleet life for all American F-35s to be $442 billion higher than U.S. Air Force projections.[213] F-35 delays have led to shortfall of up to 100 jet fighters in the Navy/Marines team, although measures have been taken using existing assets to manage and reduce this shortfall.[214]

The F-35C's maiden flight took place on 7 June 2010, at NAS Fort Worth JRB. A total of 11 U.S. Air Force F-35s arrived in fiscal year 2011.[215] On 9 March 2011, all F-35s were grounded after a dual generator failure and oil leak in flight;[216] the cause of the incident was discovered to have been the result of faulty maintenance.[217] In 2012, Navy Commander Erik Etz of the F-35 program office commented that rigorous testing of the F-35's sensors had taken place during exercise Northern Edge 2011, and had served as a significant risk-reduction step.[218][219]

On 2 August 2011, an F-35's integrated power package (IPP) failure during a standard engine test at Edwards Air Force Base led to the F-35 being immediately grounded for two weeks.[220][221] On 10 August 2011, ground operations were re-instituted; preliminary inquiries indicated that a control valve did not function properly, leading to the IPP failure.[222][223] On 18 August 2011, the flight ban was lifted for 18 of the 20 F-35s; two aircraft remained grounded for lack of monitoring systems.[224] The IPP suffered a second software-related incident in 2013, this resulted in no disruption as the fleet was already grounded by separate engine issues.[225]

On 25 October 2011, the F-35A reached its designed top speed of Mach 1.6 for the first time.[226] Further testing demonstrated Mach 1.61 and 9.9g.[227] On 11 February 2013, an F-35A completed its final test mission for clean wing flutter, reporting to be clear of flutter at speeds up to Mach 1.6.[228] On 15 August 2012, an F-35B completed airborne engine start tests.[229]

During testing in 2011, all eight landing tests of the F-35C failed to catch the arresting wire; a redesigned tail hook was developed and delivered two years later in response.[230][231] In October 2011, two F-35Bs conducted three weeks of initial sea trials aboard USS Wasp.[232]

On 6 October 2012, the F-35A dropped its first bomb,[233] followed three days later by an AIM-120 AMRAAM.[234] On 28 November 2012, an F-35C performed a total of eleven weapon releases, including a GBU-31 JDAM and GBU-12 Paveway from its weapons bay in the first weapons released for the F-35C.[235] On 5 June 2013, an F-35A at the Point Mugu Sea Test Range completed the first in-flight missile launch of an AIM-120 C5 AAVI (AMRAAM Air Vehicle Instrumented). It was launched from the internal weapons bay.[236]

On 16 November 2012, the U.S. Marines received the first F-35B at MCAS Yuma, and the VMFA(AW)-121 unit is to be redesignated from a Boeing F/A-18 Hornet unit to an F-35B squadron.[237] A February 2013 Time article revealed that Marine pilots are not allowed to perform a vertical landing—the maneuver is deemed too dangerous, and it is reserved only for Lockheed test pilots.[238] On 21 March 2013, the USMC performed its first hover and vertical landing with an F-35B outside of a testing environment.[239] On 10 May 2013, the F-35B completed its first vertical takeoff test.[240] On 3 August 2013, the 500th vertical landing of an F-35 took place.[241]

On 18 January 2013, the F-35B was grounded after the failure of a fueldraulic line in the propulsion system on 16 January.[242] The problem was traced to an "improperly crimped" fluid line manufactured by Stratoflex.[243][244] The Pentagon cleared all 25 F-35B aircraft to resume flight tests on 12 February 2013.[245] On 22 February 2013, the U.S. Department of Defense grounded the entire fleet of 51 F-35s after the discovery of a cracked turbine blade in a U.S. Air Force F-35A at Edwards Air Force Base.[246] On 28 February 2013, the grounding was lifted after an investigation concluded that the cracks in that particular engine resulted from stressful testing, including excessive heat for a prolonged period during flight, and did not reflect a fleetwide problem.[247][248] The F-35C Lightning II carrier variant Joint Strike Fighter conducted its first carrier-based night flight operations aboard an aircraft carrier off the coast of San Diego on 13 November 2014.[249]

On 5 June 2015, the U.S. Air Education and Training Command Accident Investigation Board reported that catastrophic engine failure had led to the destruction of an Air Force F-35A assigned to the 58th Fighter Squadron at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, on 23 June 2014. The third-stage forward integral arm of a rotor had fractured and broke free during the takeoff roll. Pieces cut through the engine's fan case, engine bay, internal fuel tank and hydraulic and fuel lines before leaving through the aircraft's upper fuselage. Leaked fuel and hydraulic fluid ignited the fire, which destroyed the rear two-thirds of the aircraft. The destruction of the airframe resulted in the cancelation of the F-35's international debut at the 2014 Farnborough Airshow in England, the temporary grounding of the F-35 fleet[250] and ongoing restrictions in the flight envelope.[251]

On 19 June 2015 the RAF successfully launched two 500 lb Paveway IV precision-guided bombs, making the test the first time non-US munitions were deployed by the aircraft.[252]

The US Marines declared the aircraft had met initial operational capability on 31 July 2015, despite shortcomings in night operations, communications, software and weapons carriage capabilities.[253] However, J. Michael Gilmore, director of the Pentagon’s Operational Test and Evaluation Office, criticized the operational trials as not valid. In an internal memo, Gilmore concluded "the exercise was so flawed that it 'was not an operational test … in either a formal or informal sense of the term.' Furthermore, the test 'did not—and could not—demonstrate' that the version of the F-35 that was evaluated 'is ready for real-world operational deployments, given the way the event was structured.'"[254]

On 11 April 2016 the Joint Program Office confirmed that the Royal Netherlands Air Force (RNLAF) had cleared its KDC-10 aerial tanker to refuel the F-35, paving the way for the fighter’s international public debut at the RNLAF’s Open Dagen (Open Days) at Leeuwarden on June 10–11, 2016. The testing required the fighter to refuel in daylight, dusk and night, with 30,000 lb. of fuel being transferred during the tests.[255]

The Israel Air Force declared its F-35 fleet operationally capable on December 6, 2017.[256]

Training

In 2011, the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation warned that the USAF's plan to start unmonitored flight training "risks the occurrence of a serious mishap".[257] The leaders of the United States Senate Committee on Armed Services called on Defense Secretary Leon Panetta to address the issue.[258] Despite the objections, expanded trial flights began in September 2012.[259]

The F-35A and F-35B were cleared for flight training in early 2012.[260] A military flight release for the F-35A was issued on 28 February 2012.[261] The aircraft were restricted to basic maneuvers with no tactical training allowed.[262] On 24 August 2012, an F-35 flew its 200th sortie while at Eglin Air Force Base, flown by a Marine pilot. The pilot said, "The aircraft have matured dramatically since the early days. The aircraft are predictable and seem to be maintainable, which is good for the sortie production rate. Currently, the flight envelope for the F-35 is very, very restricted, but there are signs of improvement there too". The F-35s at the base no longer need to fly with a chase aircraft and are operating in a normal two-ship element.[263]

On 21 August 2012, J. Michael Gilmore wrote that he would not approve the Operational Test and Evaluation master plan until his concerns about electronic warfare testing, budget and concurrency were addressed.[264] On 7 September 2012, the Pentagon failed to approve a comprehensive operational testing plan for the F-35.[265] Instead, on 10 September 2012, the USAF began an operational utility evaluation (OUE) of the F-35A entire system, including logistical support and maintenance, maintenance training, pilot training, and pilot execution.[266] By 1 October, the OUE was reported as "proceeding smoothly", pilots started on simulators prior to flying on 26 October.[267] The OUE was completed on 14 November with the 24th flight, the four pilots involved having completed six flights each.[268]

During the Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) phase of the aircraft, the U.S. had taken a tri-service approach to developing tactics and procedures for the F-35 using flight simulators prior to the type entering service. Simulated flights had tested the flight controls' effectiveness, helping to discover technical problems and refine aircraft design.[269] Maintenance personnel have discovered that it is often possible to correct deficiencies in the F-35, which is a software-defined aircraft, simply by rebooting the aircraft's software and onboard systems.[270]

Air Force pilot training F-35A began in January 2013 at Eglin Air Force Base; the program currently has a maximum capacity of 100 military pilots and 2,100 maintainer students.[271]

On 23 June 2014, an F-35A experienced a fire in the engine area during its takeoff at Eglin AFB. In response, the Pentagon's Joint Program Office halted training in all F-35 models the next day,[272][273] and on 3 July, the F-35 fleet was formally grounded.[274] The fleet was returned to flight on 15 July,[275] but the engine inspection regimen caused the aircraft's debut at the Farnborough 2014 Air Show to be canceled.[276][277]

At Red Flag 2017 the F-35 scored a kill ratio of 15:1 against an F-16 aggressor squadron.[278]

Basing plans for future U.S. F-35s

On 9 December 2010, a media report stated that the "USMC will base 216 F-35Bs on the East Coast and 184 of them on the West Coast, documents showed". This report continued: "Cherry Point will get 128 jets to form eight squadrons; Beaufort will have three squadrons and a pilot training center using 88 aircraft; Miramar will form six operational squadrons with 96 jets and 88 F-35s will go to Yuma for five operational squadrons with an additional test and evaluation unit".[279]

In 2011, the USMC and USN signed an agreement that the USMC will purchase 340 F-35B and 80 F-35C fighters. The five squadrons of USMC F-35Cs would be assigned to Navy carriers while F-35Bs would be used ashore.[280][281]

In February 2014, the U.S. Air Force announced that the first Air National Guard unit to fly the new F-35 Lightning II will be the 158th Fighter Wing of the Vermont Air National Guard based at the Burlington Air Guard Station. The 158th currently flies F-16 Fighting Falcons, which are nearing the end of their useful service lives. Burlington Air Guard Station is expected to receive 18 F-35As, replacing the 18 F-16 Fighting Falcons currently assigned. The F-35A is expected to arrive in 2020.[282]

On 11 March 2014, the first F-35A Lightning II assigned to Luke Air Force Base arrived at the base. 16 F-35s are to be delivered to the base by the end of 2014, with 144 Lightning IIs to be stationed there, arriving over the course of the next decade.[283][284]

On 8 January 2015, the Royal Air Force base RAF Lakenheath in the UK was chosen as the first base in Europe to station two American F-35 squadrons, following an announcement by the Pentagon. 48 F-35s, making up 2 squadrons, will add to the 48th Fighter Wing's already existing F-15C and F-15E Strike Eagle jets.[285]

Combat operation

On 22 May 2018, the Israeli Air Force chief Amikam Norkin said that the Israeli Air Force had employed the F-35 in two attacks on two different battle fronts, the first time any F-35 was used in a combat operation by any country.[286][287] The air force chief said the plane had been flown "all over the Middle East", and showed conference participants photos of an Israeli F-35 flying over Beirut in a daylight flight.[22][288]

On 27 September 2018, A United States Marines Corps F-35B was used against a Taliban target in Afghanistan, the first U.S. combat employment. The F-35B took off from the USS Essex amphibious assault ship in the Arabian Sea.[289]

Accidents

On 23 June 2014, an F-35A preparing to take off on a training flight at Eglin Air Force Base experienced a fire in the engine area. The pilot escaped unharmed. The accident caused all training to be halted on 25 June, and all flights halted on 3 July.[272][273][274] During the incident investigation, engine parts from the burned aircraft were discovered on the runway, indicating it was a substantial engine failure.[290] The fleet was returned to flight on 15 July with restrictions in the flight envelope.[275] Preliminary findings suggests that excessive rubbing of the engine fan blades created increased stress and wear and eventually resulted in catastrophic failure of the fan.[291]

In early June 2015, the USAF Air Education and Training Command (AETC) issued its official report on the incident. It found that the incident was the result of a failure of the third stage rotor of the engine's fan module. The report explained that "pieces of the failed rotor arm cut through the engine's fan case, the engine bay, an internal fuel tank, and hydraulic and fuel lines before exiting through the aircraft's upper fuselage". Pratt & Whitney, the engine manufacturer, developed two remedies to the problem. The first is an extended "rub-in" to increase the gap between the second stator and the third rotor integral arm seal. The second is the redesign to pre-trench the stator. Both were scheduled for completion by early 2016. Cost of the problem was estimated at US$50 million. All aircraft resumed operations within 25 days of the incident.[292]

On 28 September 2018, a USMC F-35B crashed near Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, South Carolina after the pilot ejected safely. This was the first F-35 crash.[293][294]

Procurement and international participation

While the United States is the primary customer and financial backer, along with the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Canada, Turkey, Australia, Norway, and Denmark have agreed to contribute US$4.375 billion towards development costs.[295] Total development costs are estimated at more than US$40 billion. The purchase of an estimated 2,400 aircraft is expected to cost an additional US$200 billion.[296] The initial plan was that the nine major partner nations would acquire over 3,100 F-35s through 2035.[297] Sales to partner nations are made through the Pentagon's Foreign Military Sales program.[298]

There are three levels of international participation.[299] The levels generally reflect financial stake in the program, the amount of technology transfer and subcontracts open for bid by national companies, and the order in which countries can obtain production aircraft. The United Kingdom is the sole "Level 1" partner, contributing US$2.5 billion, which was about 10% of the planned development costs[300] under the 1995 Memorandum of Understanding that brought the UK into the project.[301] Level 2 partners are Italy, which is contributing US$1 billion; and the Netherlands, US$800 million. Level 3 partners are Turkey, US$195 million; Canada, US$160 million; Australia, US$144 million; Norway, US$122 million and Denmark, US$110 million. Israel and Singapore have joined as Security Cooperative Participants (SCP).[302][303][304] In particular, there are signs that the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) is interested, as the force has indicated that it is seriously evaluating a potential purchase[305] and the defense minister has indicated that an F-16 replacement will be announced soon.[306]

Japan announced on 20 December 2011 its intent to purchase 42 F-35s with deliveries beginning in 2016 to replace the F-4 Phantom II; Japan seeks 38 F-35s, to be assembled domestically.[307]

By 2012, many changes had occurred in the order book. Italy became the first country to announce a reduction of its overall fleet procurement, cutting its buy from 131 to 90 aircraft. Other nations reduced initial purchases or delayed orders while still intending to purchase the same final numbers. The United States canceled the initial purchase of 13 F-35s and postponed orders for another 179. The United Kingdom cut its initial order and delayed a decision on future orders. Australia decided to buy the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet as an interim measure. Turkey also cut its initial order of four aircraft to two, but confirmed plans to purchase 100 F-35As.[308][309] Turkey will buy four F-35s to be delivered in 2015 and 2016, while the order may be increased from 100 to 120 aircraft.[310] These changes resulted in increased procurement prices, and increased the likelihood of further cuts.[311][312]

On 3 April 2012, the Auditor General of Canada Michael Ferguson published a report outlining problems with Canada's procurement of the jet, including misinformation over the final cost. According to the Auditor General, the government knowingly understated the final price of the 65 jets by $10 billion.[313] Canada's Conservative government had stated it would not reduce its order, and anticipated a $75–80 million unit cost; the procurement was termed a "scandal" and "fiasco" by the media and faced a full review to determine any Canadian F-35 purchase.[314][315][316] On 13 December 2012, in a scathing editorial published by CBC News, journalist Brian Stewart termed the F-35 project a "global wrecking ball" for its runaway costs and lack of affordability for many participating nations.[317] The Canadian government ultimately decided not to proceed with sole-sourced purchase of the fighter and commenced a competition to choose a different aircraft.[318]

In May 2013, Lockheed Martin declared that Turkey is projected to earn $12 billion from licensed production of F-35 components.[319][320]

In November 2014, the United Kingdom confirmed its first order for 14 F-35Bs to be delivered in 2016.[321]

In June 2018, the U.S. Senate blocked the transfer of F-35 fighter jets to Turkey over concerns of secrecy.[322]

Variants

The F-35 is being built in three different main versions to suit various combat missions.

F-35A

The F-35A is the conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL) variant intended for the U.S. Air Force and other air forces. It is the smallest, lightest F-35 version and is the only variant equipped with an internal cannon, the GAU-22/A. This 25 mm cannon is a development of the GAU-12 carried by the USMC's AV-8B Harrier II. It is designed for increased effectiveness against ground targets compared to the 20 mm M61 Vulcan cannon carried by other USAF fighters.

The F-35A is expected to match the F-16 in maneuverability and instantaneous high-g performance, and outperform it in stealth, payload, range on internal fuel, avionics, operational effectiveness, supportability, and survivability.[323] It is expected to match an F-16 that is carrying the usual external fuel tank in acceleration performance.[324]

The A variant is primarily intended to replace the USAF's F-16 Fighting Falcon. At one point it was also intended to replace the A-10 Thunderbolt II starting in 2028.[325][326] The F-35A can be outfitted to receive fuel via either of the two main aerial refueling methods; this was a consideration in the Canadian procurement and a deciding factor for the Japanese purchase.[327][328][329] On 18 December 2013, the Netherlands became the second partner country to operate the F-35A, when Maj. Laurens J.W. Vijge of the Royal Netherlands Air Force took off from Eglin Air Force Base.[330]

The F-35As for the Royal Norwegian Air Force will have drag chute installed. Norway will be the first country to adopt the drag chute pod.[331]

On 2 August 2016, the U.S. Air Force declared the F-35A basic combat ready.[332] The 34th Fighter Squadron located at Hill Air Force Base, Utah, has at least 12 combat-ready jets capable of global deployment. The F-35A is scheduled to be fully combat ready in 2017 with its 3F software upgrade. Air Combat Command will initially deploy F-35A to Red Flag exercises and as a "theater security package" to Europe and the Asia-Pacific. It will probably not be fighting the Islamic State in the Middle East earlier than 2017.[333]

On 13 July 2017, UK Minister of State For Defence Frederick Curzon confirmed that the UK will purchase a minimum 138 aircraft and a decision will shortly be forthcoming as whether there will be a 'mix' of F-35A and 'B' versions required for 'synergy' and 'inter-service operability' between the RAF and Royal Navy.[334][335][336]

F-35B

The F-35B is the short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) variant of the aircraft. Similar in size to the A variant, the B sacrifices about a third of the A variant's fuel volume to accommodate the vertical flight system. Vertical takeoffs and landings are riskier because of threats such as foreign object damage.[337][338] Whereas the F-35A is stressed to 9 g,[339][340] the F-35B's stress goal is 7 g. As of 2014, the F-35B is limited to 4.5 g and 400 knots. The next software upgrade includes weapons, and allows 5.5 g and Mach 1.2, with a final target of 7 g and Mach 1.6.[341] The first test flight of the F-35B was conducted on 11 June 2008.[342] Another milestone, the first successful ski-jump launch was carried out by BAE test pilot Peter Wilson on 24 June 2015.[343]

Unlike other variants, the F-35B has no landing hook. The "STOVL/HOOK" control instead engages conversion between normal and vertical flight.[344] Jet thrust is sent directly downwards during vertical flight. The variant's three-bearing swivel nozzle that directs the full thrust of the engine is moved by a "fueldraulic" actuator using pressurized fuel as the working fluid.[345]

The U.S. Marine Corps plans to purchase 340 F-35B and 80 F-35C models[346] to replace current inventories of both the F/A-18 Hornet (A, B, C and D-models), and the AV-8B Harrier II, in the fighter and attack roles.[347] The Marines plan to use the F-35B from "unimproved surfaces at austere bases" but with "special, high-temperature concrete designed to handle the heat".[348][349] The USMC declared initial operational capability with about 50 F-35s running interim block 2B software on 31 July 2015.[350] The USAF had considered replacing the A-10 with the F-35B, but will not do so because of the F-35B's inability to generate enough sorties.[351]

On 6 January 2011, Gates said that the 2012 budget would call for a two-year pause in F-35B production during which the aircraft faced redesign, or cancellation if unsuccessful.[352] In 2011, Lockheed Martin executive vice president Tom Burbage and former Pentagon director of operational testing Tom Christie stated that most program delays were due to the F-35B, which forced massive redesigns of other versions.[353] Lockheed Martin Vice President Steve O’Bryan has said that most F-35B landings will be conventional to reduce stress on vertical lift components.[354] These conventional mode takeoffs and landings cause an "unacceptable wear rate" to the aircraft's "poorly designed" tires.[355] USMC Lt. Gen. Robert Schmidle has said that the vertical lift components would only be used "a small percentage of the time" to transfer the aircraft from carriers to land bases.[356] On 3 October 2011, the F-35B began its initial sea-trials by performing a vertical landing on the deck of the amphibious assault ship USS Wasp,[357] to continue in 2015.[358] Probation status was reportedly ended by Defense Secretary Leon Panetta in January 2012 based on progress made.[359] A heat-resistant anti-skid material called Thermion is being tested on Wasp, also useful against the V-22 exhaust.[360]

Britain's Royal Air Force and Royal Navy plan to introduce the F-35B as a replacement for the Harrier GR9, which was retired in 2010, and Tornado GR4, which will retire in 2019. The F-35 is intended to be the United Kingdom's primary strike attack aircraft for the next three decades. One of the Royal Navy requirements for the F-35B design was a Shipborne Rolling and Vertical Landing (SRVL) mode to increase maximum landing weight to bring back unused ordnance by using wing lift during landing.[361][362] In July 2013, Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Dalton announced that 617 Squadron would be the first operational Royal Air Force squadron to receive the F-35.[363][364] The second operational squadron will be the Fleet Air Arm's 809 NAS.[365] In June 2013, the Royal Air Force had received three aircraft of the 48 on order, all of which based at Eglin Air Force base.[366] The F-35 will be based at Royal Air Force Marham and become operational in 2018.[367][368] In June 2015, the F-35B undertook its first launches from a ski-jump, when one of the UK's aircraft took off using a ramp constructed at NAS Patuxent River.[369] When required to operate from the sea, the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy will operate the F-35B from ships fitted with ski-jumps, as will the Italian Marina Militare. In 2011, the Marina Militare was preparing Grottaglie Air Station for F-35B operations; they are to receive 22 aircraft between 2014 and 2021, with the aircraft carrier Cavour set to be modified to operate them by 2016.[370] The British version of the F-35B is not intended to receive the Brimstone 2 missile.[371]

Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, General James Amos has said that, in spite of increasing costs and schedule delays, there is no plan B to the F-35B.[372] The F-35B is larger than the aircraft it replaces, which required USS America to be designed without well deck capabilities.[373] In 2011, the USMC and USN signed an agreement by which the USMC will purchase 340 F-35B and 80 F-35C fighters, while the USN will purchase 260 F-35Cs. The five squadrons of USMC F-35Cs will be assigned to Navy carriers; F-35Bs will be used on amphibious ships and ashore.[280][281]

Although the Australian Canberra-class landing helicopter dock ships were not originally planned to operate fixed-wing aircraft, in May 2014, the Minister for Defence David Johnston stated in media interviews that the government was considering acquiring F-35B fighters for Canberras, and Prime Minister Tony Abbott instructed 2015 Defence White Paper planners to consider the option of embarking F-35B squadrons aboard the two ships.[374][375][376] Supporters of the idea stated that providing fixed-wing support to amphibious operations would maximize aircraft capability, and the presence of a ski-jump ramp, inherited from the original design, meant that the vessels were better suited to STOVL operations than equivalent ships with flat flight decks.[377] Opponents to the idea countered that embarking enough F-35Bs to be effective required abandoning the ships' amphibious capability and would make the pseudo-carriers more valuable targets, modifications would be required to make the flight deck capable of handling vertical-landing thrust and to increase fuel and ordnance capacity for sustained operations, and that the F-35B project itself has been the most expensive and most problematic of the Joint Strike Fighter variants.[378][379][380] In July 2015 Australia ended consideration of buying the F-35B for its two largest assault ships, as the ship modifications were projected to cost more than AUS$5 billion (US$4.4 billion). The plan was opposed by the Royal Australian Air Force, as an F-35B order could have diminished the number of F-35As purchased.[381][382]

The U.S. Marine Corps plans to disperse its F-35Bs among forward deployed bases to enhance survivability while remaining close to a battlespace, similar to RAF Harrier deployment late in the Cold War, which relied on the use of off-base locations that offered short runways, shelter, and concealment. Known as distributed STOVL operations (DSO), Marine F-35Bs would sustain operations from temporary bases in allied territory within the range of hostile ballistic and cruise missiles, but be moved between temporary locations inside the enemy's 24- to 48-hour targeting cycle. This strategy accounts for the F-35B's short range, the shortest of the three variants, with mobile forward arming and refueling points (M-Farps) accommodating KC-130 and MV-22 Osprey aircraft to rearm and refuel the jets, as well as littoral areas for sea links of mobile distribution sites on land. M-Farps could be based on small airfields, multi-lane roads, or damaged main bases, while F-35Bs would return to U.S. Navy ships, rear-area U.S. Air Force bases, or friendly carriers for scheduled maintenance; metal planking would be needed to protect unprepared roads from the F-35B's engine exhaust, which would be moved between sites by helicopters, and the Marines are studying lighter and more heat-resistant products.[383]

On 27 September 2018 an F-35B from the USS Essex carried out an air strike using a precision-guided bomb against a Taliban position in Afghanistan, marking the first US combat use of the F-35.[384]

F-35C

Compared to the F-35A, the F-35C carrier variant features larger wings with foldable wingtip sections, larger wing and tail control surfaces for improved low-speed control, stronger landing gear for the stresses of carrier arrested landings, a twin-wheel nose gear, and a stronger tailhook for use with carrier arrestor cables. The larger wing area allows for decreased landing speed while increasing both range and payload.

The United States Navy intends to buy 260 F-35Cs to replace the F/A-18A, B, C, and D Hornets and complement the Super Hornet fleet.[280][385] On 27 June 2007, the F-35C completed its Air System Critical Design Review (CDR), allowing the production of the first two functional prototypes.[386] The C variant was expected to be available beginning in 2014.[387] The first F-35C was rolled out on 29 July 2009.[388] The United States Marine Corps will also purchase 80 F-35Cs, enough for five squadrons, for use with navy carrier air wings in a joint service agreement signed on 14 March 2011.[280][281] A recent 2014 document stated that the USMC will also have 4 squadrons of F-35Cs with 10 aircraft per squadron for the Marine Corps' contribution to U.S. Navy carrier air wings.[389]

On 6 November 2010, the first F-35C arrived at Naval Air Station Patuxent River. In 2011, the F-35Cs were grounded for six days after a software bug was found that could have prevented the control surfaces from being used during flight.[390] On 27 July 2011, the F-35C test aircraft CF-3 completed its first steam catapult launch during a test flight at Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst; the TC-13 Mod 2 test steam catapult, representative of current fleet technology, was used. In addition to catapult launches at varying power levels, a three-week test plan included dual-aircraft jet blast deflector testing and catapult launches using a degraded catapult configuration to measure the effects of steam ingestion on the aircraft.[391]

On 13 August 2011, the F-35 successfully completed jet blast deflector (JBD) testing at Lakehurst. F-35C test aircraft CF-1 along with an F/A-18E tested a combined JBD cooling panel configuration. The tests measured temperature, pressure, sound level, velocity, and other environmental data; the JBD model will enable the operation of all carrier aircraft, including the F-35C. Further carrier suitability testing continued in preparation for initial ship trials in 2013.[392] On 18 November 2011, the U.S. Navy used its new Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) to launch an F-35C into the air for the first time.[393]

On 22 June 2013, Strike Fighter Squadron VFA-101 received the Navy's first F-35C at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida.[394][395]

The USN is dealing with the following issues in adapting their carriers to operate the F-35C.[396]

- The fighter's F135 engine exceeds the weight capacity of traditional underway replenishment systems[397] and generates more heat than previous engines.

- The stealthy skin requires new repair techniques; extensive skin damage will necessitate repairs at Lockheed's land-based facilities.

- The adoption of lithium-ion batteries needing careful thermal management, and higher voltage systems than traditional fighters.

- Storing of new weapons not previously employed on carrier aircraft.

- Large quantities of classified data generated during missions shall require additional security.

In February 2014, Lockheed said the F-35C was on schedule for sea trials after the tailhook was redesigned. The new tailhook has a different shape to better catch arresting wires. Testing on land achieved 36 successful landings. Sea trials were scheduled for October 2014.[398]

On 3 November 2014, an F-35C of VX-23, one of the Navy's flight test units, made its first landing on an aircraft carrier when it recovered aboard USS Nimitz; this started a two week deployment of a pair of aircraft for the initial at sea Development Testing I or DTI, the first of three at sea tests planned for the F-35C.[399][400] The initial deployment was completed on November 14.[401]

The U.S. Navy may use the F-35C as part of its UCLASS effort to operate a carrier-based unmanned aerial vehicle. Though it has been suggested that the UCLASS could carry air-to-air weapons, an unmanned aircraft lacks situational awareness and is more vulnerable to electronic countermeasures than manned aircraft, and autonomy for deploying lethal weapons is not under development. With the F-35C as the center of a network of naval systems, it could feed information to the UCLASS and order it to fire on a certain target. Large numbers of F-35Cs operating in contested environments can generate a clear picture of the battlespace, and share it with unmanned assets that can be directed to attack.[402]

VFA-147 was selected to be the first operational squadron to transition to the F-35C in January 2018. Operational testing was to continue aboard USS Abraham Lincoln at the beginning of 2018. The carrier is the first to be modernized to operate the F-35C. Initial operating capability is expected between mid-2018 and early 2019, with the first deployment is scheduled aboard USS Carl Vinson in 2020. The F-35C will equip two of the four strike fighter squadrons in a carrier air wing.[403]

Other versions

F-35I

The F-35I Adir (Hebrew: אדיר, meaning "Awesome",[404] or "Mighty One"[405]) is an F-35A with Israeli modifications. A senior Israel Air Force official stated "the aircraft will be designated F-35I, as there will be unique Israeli features installed in them". Despite an initial refusal to allow such modifications, the U.S. has agreed to let Israel integrate its own electronic warfare systems, such as sensors and countermeasures, into the aircraft. The main computer will have a plug-and-play feature to allow add-on Israeli electronics to be used; proposed systems include an external jamming pod, and new Israeli air-to-air missiles and guided bombs in the internal weapon bays.[406][407]

Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) has considered playing a role in the development of a proposed two-seat F-35; an IAI executive stated: "There is a known demand for two seats not only from Israel but from other air forces".[408] IAI plans to produce conformal fuel tanks.[409] A senior IAF official stated that elements of the F-35's stealth may be overcome in 5 to 10 years, while the aircraft will be in service for 30 to 40 years, which is why Israel insisted on installing their own electronic warfare systems: "The basic F-35 design is OK. We can make do with adding integrated software".[410] Israel is interested in purchasing up to 75 F-35s.[411]

On 12 December 2016, Israel began receiving its first F-35Is of the 50 it plans to purchase for integration and testing. Israel is to be the second nation with an operational F-35 squadron following the U.S.[412][413][414] The first nine F-35s became operational (at initial operating capacity) in the Israeli Air Force in December 2017.[415] On May 22, 2018, Israel's Air force commander, Major General Amikam Norkin, reported that Israel became the first country in the world to use the F-35 in combat during recent clashes with Iran in Syria.[416] According to the IDF, the F-35 was used in combat for the first time in 2018, has been "flying all over the Middle East",[22] and had carried out the plane's first combat airstrikes in the world on two different Middle Eastern battlefronts.[22]

CF-35

The Canadian CF-35 is a proposed variant that would differ from the F-35A through the addition of a drogue parachute and may include an F-35B/C-style refueling probe.[331][417] In 2012, it was revealed that the CF-35 would employ the same boom refueling system as the F-35A.[418] One alternative proposal would have been the adoption of the F-35C for its probe refueling and lower landing speed; however, the Parliamentary Budget Officer's report cited the F-35C's limited performance and payload as being too high a price to pay.[419] Following the 2015 Federal Election the Liberal Party, whose campaign had included a pledge to cancel the F-35 procurement,[420] won a majority in the House of Commons. The new government stated it would run a competition for an aircraft to replace the existing CF-18 Hornet.[421]

F-35D

Early-stage design study for a possible upgrade of the F-35A to be fielded by the 2035 target date of the Air Force Future Operating Concept.[422][423]

Operators

F-35A

- Royal Australian Air Force – 9 delivered,[424] 63 on order,[425] up to 28 additional planned[426]

- Royal Danish Air Force – 27 planned[427]

- Israeli Air Force – 12 delivered (9 operational) (F-35I).[428] 50 ordered in total, from a total of 75 planned for the near future.[429][430]

- Italian Air Force – 9 operational and, 2 more on order with 17 more ordered for delivery up to 2019;[435][436] up to 60 total planned.[437]

- 32º Stormo

- Japan Air Self-Defense Force – 1 operational and 9 remaining on order;[438][439] 42 planned[440] of which 38 are being built by Mitsubishi.[441][442]

- Royal Netherlands Air Force – 2 in use for testing, 8 on order, 27 additional planned[443][444]

- 323 Squadron[445]