Moroccan Western Sahara Wall

| Part of a series on the |

| Western Sahara conflict |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Disputed regions |

| Politics |

| Clashes |

| Issues |

| Peace process |

The Moroccan Western Sahara Wall is an approximately 2,700 km (1,700 mi) long structure, mostly a sand wall (or "berm"), running through Western Sahara and the southwestern portion of Morocco. It separates[1] the Moroccan-occupied and -controlled areas (the Southern Provinces) on the west from the Polisario-controlled areas (Free Zone, nominally Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic) on the east.

According to maps from the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO)[2] or the UNHCR,[3] the wall extends several kilometres (a few miles) into internationally recognized Mauritanian territory.[4]

Physical structure

The fortifications lie in uninhabited or very sparsely inhabited territory. They consist of sand and stone walls or berms about 3 m (10 ft) in height, with bunkers, fences and landmines throughout. The barrier minebelt that runs along the structure is thought to be the longest continuous minefield in the world.[5] Military bases, artillery posts and airfields dot the Moroccan-controlled side of the wall at regular intervals, and radar masts and other electronic surveillance equipment scan the areas in front of it.

The following is one observer's description of the Berm from 2001:

Physically, the berm is a 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high wall (with a backing trench), which rides along a topographical high point/ridge/hill throughout the territory. Spaced out over every 5 km (3.1 mi) are big, small and medium bases, with approximately 35–40 troops at each observation post and groups of 10 soldiers spaced out over the distance as well. About 4 km (2 1⁄2 mi) behind each major post there is a rapid reaction post, which includes backing mobile forces (tanks, etc). A series of overlapping fixed and mobile radars are also positioned throughout the berm. The radars are estimated to have a range of between 60 and 80 km (37 and 50 mi) into the Polisario controlled territory, and are generally utilized to locate artillery fire onto detected Polisario forces. Information from the radar is processed by a forward-based commander, who contacts a rear-based artillery unit.[6]

In all, six lines of berms have been constructed.[7] The main ("external") line of fortifications extends for about 2,500 km (1,600 mi). It runs east from Guerguerat on the coast in the extreme south of Western Sahara near the Mauritanian town of Nouadhibou, closely parallelling the Mauritanian border for about 200 km (120 mi), before turning northwards beyond Techla. It then runs generally northeastward, leaving Guelta Zemmur, Smara, crossing again Mauritanian territory and reaching Hamza in Moroccan-held territory, before turning east and again closely following the Algerian border as it approaches Morocco. A section extends about 200 km (120 mi) into southeastern Morocco.[8][9]

Significant lines of fortifications also lie deep within the Moroccan-controlled area.[10] Their exact number and location are a source of some confusion for overseas commentators.[11]

All major settlements, the capital Laayoun, and the phosphate mine at Bou Craa lie far into the Moroccan-held side.

The fortifications were progressively built by Moroccan forces starting in 1981, and formally ending on 16 April 1987.[7] Their main function is to exclude guerrilla fighters of the Polisario Front, who have sought Western Saharan independence since before Spain ended its colonial occupation in 1975, from the Moroccan-controlled part of the territory.[12]

Consequence

Effectively, after the completion of the wall, Morocco has controlled the bulk of Western Sahara territory that lies to the north and west of it, calling these the kingdom's "Southern Provinces". The Polisario-founded Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic controls the mostly uninhabited "Free Zone", which comprises all areas to the east of the barrier. Units from the United Nations mission MINURSO separate the two sides, and enforce cease-fire regulations on their troops.

International reaction and incidents

In the summer of 2005, the Moroccan Army accelerated the expulsion (started in late 2004) of illegal immigrants detained in northern Morocco to the eastern side of the wall, into the Free Zone. The Polisario Front and the MINURSO rescued several dozen lost in the desert, who had run out of water. Others died of thirst.[13] By October, the Polisario had received 22 immigrants in Mehaires, 46 in Tifariti and 97 in Bir Lehlu. They were from African countries (Gambia, Cameroon, Nigeria, Ghana, etc.), except a group of 48 who were from Bangladesh.[14][15]

Western attention to the wall, and to the Moroccan annexation of the Western Sahara in general, has been minimal, apart from Spain. In Africa, the annexation of Western Sahara by Morocco has attracted somewhat more attention. Algeria supports the Polisario Front "in its long-running desert war to oppose Moroccan control of the disputed area".[16][17] The Organization of African Unity/African Union and United Nations have proposed negotiated solutions, though the African Union's stance on Western Sahara led to Morocco's exit from the organisation. January 30, 2017 Morocco rejoined the African Union after a 33-year absence despite resistance from member states over the status of Western Sahara. Al Jazeera wrote that 9 states voted against while 39 states supported Morocco's bid into the African Union (AU).[18] Morocco had been re-admitted with the understanding that Western Sahara will remain a member of the AU. The membership of relatively wealthy Morocco was welcomed by many members of the AU, which has been criticized for being overly dependent on non-African donor funding.

The Thousand Column

Since 2008, a demonstration called "The Thousand Column" is held annually in the desert against the barrier by international human rights activists and Sahrawi refugees. In the 2008 demonstration, more than 2,000 people (most of them Sahrawis and Spaniards, but also Algerians, Italians, and others) made a human chain demanding the demolition of the wall, the celebration of the self-determination referendum accorded by the UN and the parts in 1991, and the end of the Moroccan occupation of the territory.[19]

In the 2009 edition, a teenage Sahrawi refugee named Ibrahim Hussein Leibeit lost half of his right leg in a landmine explosion.[20][21] The incident happened when Ibrahim and dozens of young Sahrawis crossed the line into a minefield while aiming to throw stones to the other side of the wall.[22][23]

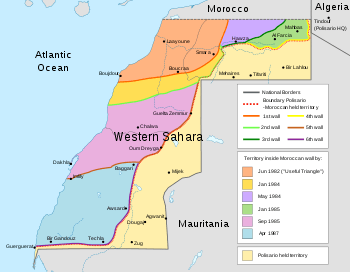

Construction of the wall

The wall was built in six stages, and the area behind the wall was expanded from a small area near Morocco in the north to most of the western and central part of the country gradually. The walls built were:

- 1st wall (Aug 1980 – Jun 1982) surrounding the "useful triangle" of El Aaiún, Smara and the phosphate mines at Bou Craa (c. 500 km (310 mi)).

- 2nd wall (Dec 1983 – Jan 1984) surrounding Amgala (c. 300 km (190 mi)).

- 3rd wall (Apr 1984 – May 1984) surrounding Jdiriya and Haouza (c. 320 km (200 mi)).

- 4th wall (Dec 1984 – Jan 1985) surrounding Mahbes and Farciya (c. 380 km (240 mi))

- 5th wall (May–Sep 1985) surrounding Guelta Zemmur, Bir Anzarane and Dakhla (c. 670 km (420 mi))

- 6th wall (Feb–Apr 1987) surrounding Auserd, Tichla and Bir Ganduz (c. 550 km (340 mi))

Gallery

Wall east of Mahbes

Wall east of Mahbes Wall south of Mahbes

Wall south of Mahbes

Satellite views

(Google Maps)

- Fence with accumulated sand

- Wall with fort

- Wall smothered by dune with fort nearby

- Wall smothered by dune with fort

- Road cut by fence

- Sand piled up high on the wall

- 5th wall with inhabited mesa

- Disused fort on 5th wall

- Abandoned fort and section of 5th wall

- Sand piled up high on the wall

- End of the road in the south with compound and fort

- Wall going over an abandoned fort

- In mountainous terrain

- Forts in the south

- Fort and wall

See also

References and notes

- ↑ "However, with the completion of the Moroccan separation wall in the 1980s,..." "separation+wall"&source=bl&ots=YiUO5Cpfxf&sig=I06JNC8TCsi5EzNdDKNccwD96mU&hl=iw&sa=X&ei=VZa1VNHA

- ↑ Deployment of MINURSO Archived 2007-10-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Western Sahara Atlas Map - June 2006

- ↑ MINURSO

- ↑ McCoull, Chad. "Country Profiles - Morocco and Western Sahara". Journal of Mine Action. ISSN 2154-1485.

- ↑ ARSO Website

- 1 2 Milestones of the conflict Archived 2007-02-21 at the Wayback Machine., page 2. Website of the United Nations MINURSO mission.

- ↑ United Nations Map No. 3691 Rev. 53 United Nations, October 2006 (Colour), Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Cartographic Section. Depicts the deployment of the MINURSO mission, as well as the Wall location.

- ↑ See also e.g. this satellite montage at Google Maps for a section of the wall in Moroccan territory. The northernmost fort that is clearly distinguishable can be seen here. (Google Maps, as of 30 November 2006)

- ↑ For example, a sand berm with fortifications much like on the main external line can be seen here, reaching the coast near Imlili, over 200 km north of the main external berm along the southern border. (Google Maps, as of 30 November 2006)

- ↑ (in Dutch) Marokkaanse veiligheidsmuur al twee decennia onomstreden Archived 2005-02-09 at the Wayback Machine., CIDI Israel website, Nieuwsbrief (2004)

- ↑ Maclean, Ruth (2018-09-22). "Build a wall across the Sahara? That's crazy – but someone still did it". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- ↑ "Patada al desierto" (in Spanish). Diario de Córdoba. 2005-10-17. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ↑ "El Polisario busca desaparecidos" (in Spanish). El País. 2005-10-18. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ↑ "De Bangladesh al desierto del Sáhara" (in Spanish). El País. 2005-10-19. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Security Problems with Neighboring States", Country Studies/Area Handbook Series, Library of Congress Federal Research Division (retrieved May 1, 2006).

- ↑ Williams, Ian and Zunes, Stephen, "Self Determination Struggle in the Western Sahara Continues to Challenge the UN" Archived 2007-01-09 at the Wayback Machine., Foreign Policy in Focus Policy Report, September 2003 (retrieved May 1, 2006).

- ↑ "Morocco rejoins the African Union after 33 years". Al Jazeera. 2017-01-31.

- ↑ Una cadena humana de más de 2.000 personas pide el derribo del muro del Sáhara El Mundo (EFE), 22 March 2008 (in Spanish)

- ↑ Demonstration in Western Sahara against Moroccan Army Wall Demotix, 9 April 2009

- ↑ Ibrahim Hussein Leibeit Focus Features, 28 May 2009

- ↑ Screenings in The Devil’s Garden: The Sahara Film Festival New Internationalist, Issue 422, 20 May 2009

- ↑ The Berlin Wall of the Desert New Internationalist, Issue 427, 10 November 2009

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moroccan Wall. |

- Map of Western Sahara, with the location of the wall marked Produced by the United Nations, showing the deployment of the MINURSO mission as of January 2014. Map No. 3691 Rev. 72 United Nations, January 2014 (Colour), Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Cartographic Section

- Landmine Monitor, LM Report 2006, [Morocco http://www.icbl.org/lm/2006/morocco.html ]

- Landmine Monitor, LM Report 2006, [Western Sahara http://www.icbl.org/lm/2006/western_sahara.html ]

- Landmine Monitor, LM Report 2006, [Algeria http://www.icbl.org/lm/2006/algeria ]

- online slideshow created by the United Nations MINURSO mission. Includes an aerial photograph of the barrier on slide 11.

- Fly over The Berm of Western Sahara in Google Earth Community

- The Thousand Column 2011 Official Website (in Spanish)

- Photos of the wall, landmines and Sahrawi victims Demotix, 27 December 2011