Michael Collins (astronaut)

| Michael Collins | |

|---|---|

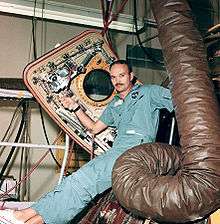

Collins in July 1969 | |

| Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs | |

|

In office January 6, 1970 – April 11, 1971 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Dixon Donnelley |

| Succeeded by | Carol Laise |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

October 31, 1930 Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | USMA, B.S. 1952 |

| Occupation | Test pilot |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | United States Air Force |

| Years of service | 1952–1970 (active duty) |

| Rank |

|

| NASA astronaut | |

| Status | Retired |

Time in space | 11 days, 2 hours, 04 minutes, 43 seconds |

| Selection | 1963 NASA Group 3 |

Total EVAs | 2 |

Total EVA time | 1 hour 28 minutes |

| Missions | Gemini 10, Apollo 11 |

Mission insignia |

|

| Retirement | January 1970 |

| Awards |

|

Michael Collins (born October 31, 1930) (Major General, USAF, Ret.) is an American former astronaut and test pilot. Selected as part of the third group of fourteen astronauts in 1963, he flew into space twice. His first spaceflight was on Gemini 10, in which he and Command Pilot John Young performed two rendezvous with different spacecraft and undertook two extra-vehicular activities (EVAs, also known as spacewalks). His second spaceflight was as the Command Module Pilot for Apollo 11. While he stayed in orbit around the Moon, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left in the Lunar Module to make the first manned landing on its surface. He is one of 24 people to have flown to the Moon. Collins was the fourth person, and third American, to perform an EVA; and is the first person to have performed more than one EVA.

Prior to becoming an astronaut, he graduated from the United States Military Academy, and from there he joined the United States Air Force and flew F-86 Sabre fighters at Chambley-Bussieres Air Base. He was accepted to the U.S. Air Force Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in 1960. He unsuccessfully applied for the second astronaut group, but was accepted for the third group.

After retiring from NASA in 1970, Collins took a job in the Department of State as Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs. A year later, he became the director of the National Air and Space Museum and held this position until 1978, when he stepped down to become undersecretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In 1980, he took the job as vice president of LTV Aerospace. Collins resigned in 1985 to start his own consulting firm. He was married to Patricia Collins until her death in April 2014. They had three children together.

Childhood and education

Collins was born in Rome, Italy, on October 31, 1930,[1][2] to U.S. Army Major General James Lawton Collins, who served in the army for 38 years.[3] For the first 17 years of his life, Collins lived in many places: Rome; Oklahoma; Governors Island, New York; Puerto Rico; San Antonio, Texas; and Alexandria, Virginia. He took his first ride in a plane in Puerto Rico aboard a Grumman Widgeon.[4] Collins studied for two years in the Academia del Perpetuo Socorro in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[5]

After the United States entered World War II, the family moved to Washington, D.C., where Collins attended St. Albans School and graduated in 1948.[6] His mother wanted him to enter into the diplomatic service, but he decided to follow his father, two uncles, brother and cousin into the armed services. He received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, which also had the advantage of being free of tuition and other fees. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree, finishing 185th out of 527 cadets in 1952, the same class as fellow astronaut Ed White. His decision to join the United States Air Force for his active service was based on both the wonder of what the next 50 years might bring in aeronautics, and also to avoid accusations of nepotism had he joined the Army where his uncle, General J. Lawton Collins, was the Chief of Staff of the United States Army.[7] The Air Force Academy was in its initial construction phase, and would not graduate its first class for several years. In the interim, graduates of the Military Academy were eligible for Air Force commissions, which Collins received.[8]

Military service

After entering the Air Force, Collins completed flight training at Columbus Air Force Base, Mississippi, in the T-6 Texan, then moved to San Marcos Air Force Base and James Connally Air Force Base, Texas. He was chosen for advanced day fighter training at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, flying F-86 Sabres. This was followed by an assignment to the 21st Fighter-Bomber Wing at George Air Force Base, California, where he learned how to deliver nuclear weapons. He transferred with the 21st when it was relocated to Chaumont-Semoutiers Air Base, France, in June 1954.[9]

During a NATO exercise in the summer of 1956, Collins was forced to eject from an F-86 after a fire started aft of the cockpit.[10] He was safely rescued and returned to Chaumont AB, where a wait of several hours ensued, as the base's flight surgeon had joined search parties looking for Collins.[11]

Collins met Patricia Finnegan, his future wife, in an officers' mess. She was from Boston, Massachusetts and was working for the Air Force service club. After getting engaged, they had to overcome a difference in religion. Collins was nominally Episcopalian, while Finnegan came from a staunchly Roman Catholic family. After seeking permission to marry from Finnegan's father, and delaying their wedding when Collins was redeployed to West Germany during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, they married in the summer of 1957.[12] They had a daughter, actress Kate Collins circa 1959.[13]

After Collins was reassigned to the United States, he attended an aircraft maintenance officer course at Chanute Air Force Base, Illinois. He would later describe this school as "dismal" in his autobiography; he found the classwork boring, flying time scarce, and the equipment outdated. Upon completing the course, he commanded a Mobile Training Detachment (MTD) and traveled to air bases around the world.[14] The detachment trained mechanics on the servicing of new aircraft and pilots how to fly them. He later commanded a Field Training Detachment (FTD), which is very similar to an MTD, except the students travel to him.[15]

Test pilot

With the help of his time as a member of an MTD, Collins accumulated over 1,500 hours of flying, the minimum required for the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California. He successfully applied and reported on August 29, 1960, becoming a member of Class 60-C (which included future astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Irwin). Following months of intensive training, Collins was one of the few chosen for a position in fighter operations.[16]

Collins used to smoke heavily, but decided to quit in 1962 after suffering a particularly bad hangover. The next day, he spent what he described as the worst four hours of his life in the right-hand seat of a bomber flicking switches while going through the initial stages of nicotine withdrawal.[17]

The turning point for Collins in his decision to become an astronaut was the Mercury Atlas 6 flight of John Glenn on February 20, 1962, and the thought of being able to circle the Earth in 90 minutes. He immediately applied for the second group of astronauts that year. To raise their numbers, the Air Force sent their best applicants to a "charm school". Medical and psychiatric examinations at Brooks Air Force Base, Texas and interviews at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston followed. In mid-September he found out he had not been accepted, it was a blow even though he did not anticipate to be accepted. Collins still rates the second group of nine as the best group of astronauts ever selected by NASA.[18]

That same year the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School became the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School, as the Air Force tried to enter into the research of space. Collins applied for a new course offered into the basics of spaceflight (other students included Charles Bassett, Edward Givens and Joe Engle). Along with classwork they also flew up to about 90,000 feet in F-104 Starfighters. As they passed through the top of their huge arc, they would experience a brief period of weightlessness. Finishing this course he returned to fighter ops in May 1963.[19]

At the start of June of that year, NASA once again called for astronaut applications. Collins went through the same process as with his first application, though he did not take the psychiatric evaluation. He was at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas on October 14 when Deke Slayton called and asked if he was still interested in becoming an astronaut. Charlie Bassett was also accepted in the same group.[20]

He has logged approximately 5,000 hours flying time.[21]

Space program

For the third group of astronauts, training began with a 240-hour course of the basics of spaceflight. Fifty-eight hours of this was devoted to geology, something that Collins did not readily understand and in which he never became very interested.[22] At the end, Alan Shepard, who was head of the astronaut office, asked the fourteen to rank their fellow astronauts in the order they would want to fly with them in space. Collins picked David Scott in the number one position.[23]

Project Gemini

After this basic training, the third group were assigned specializations, with Collins receiving his first choice of pressure suits and extravehicular activities (EVAs, also known as spacewalks). His job was to monitor the development and act as a liaison between the Astronaut Office and contractors.[24] Collins was bothered during the secretive planning of Ed White's EVA on Gemini 4, because he was not involved.[25]

In late June 1965, Collins received his first crew assignment: the backup pilot for Gemini 7.[26] He was the first of the 14 to receive a crew assignment, though would not be the first to fly; that honor went to David Scott on Gemini 8.[27]

Gemini 10

.jpg)

After the successful completion of Gemini 7, on January 24, 1966 Collins was assigned to the prime crew of Gemini 10 with John Young, with White moving onto the Apollo program.[28] Since Gemini 9's EVA ran into problems, the remaining Gemini objectives had to be completed on the last three flights. While the overall number of objectives increased, the difficulty of Collins' EVA was scaled significantly back. There was no backpack or astronaut maneuvering unit (AMU), as there had been on Gemini 8.[28]

Their three-day mission called for them to rendezvous with two different Agena Target Vehicles, undertake two EVAs, and perform 15 different experiments. The training went smoothly, as the crew learned the intricacies of orbital rendezvous, controlling the Agena and, for Collins, EVA. For what was to be the fourth ever EVA, underwater training was not performed, mostly because Collins did not have the time. To train to use the nitrogen gun he would use for propulsion, a super smooth metal surface about the size of a boxing ring was set up. He would stand on a circular pad that used gas jets to raise itself off the surface. Using the nitrogen gun he would practice propelling himself across the "slippery table".[29]

Collins and Young completed all of the major objectives of the flight.[30] The mission called for multiple dockings with the Agena target, but Collins' error in using the sextant caused them to burn valuable fuel, causing mission control to call off this objective.[31] Once docked, the Agena thrust the astronauts to a new altitude record, 474 miles above the Earth and greater than the 295 miles achieved by Voshkod 2.[32]

For his first EVA Collins did not leave the Gemini capsule, but stood up through the hatch with a device that resembled a sextant. In his biography he said he felt at that moment like a Roman god riding the skies in his chariot.[33] The EVA started on the dark side of the Earth so that Collins could take photos of the Milky Way. His eyes teared up, forcing an early end to the EVA.[34]

Prior to Collins' second EVA, the Agena spacecraft was jettisoned. Young positioned the capsule close enough to Agena 8 for Collins to get to it while attached to his 49 foot umbilical. Collins thought it took much longer to complete tasks than he expected, as Cernan had experienced during his spacewalk. He removed a micro-meteor experiment from the exterior of the spacecraft, and configured his nitrogen maneuvering thruster. Collins had difficulty re-entering the spacecraft, and required Young to pull him back in with the umbilical. The duo continued with more experiments, and then splashed down in the Atlantic, 3.5 miles from the amphibious assault ship USS Guadalcanal.[35]

Apollo program

Shortly after Gemini 10, Collins was assigned to the backup crew for the second manned Apollo flight, with Commander Frank Borman, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Thomas Stafford and Collins as Lunar Module Pilot (LMP). Along with learning the new Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM) and the Apollo Lunar Module (LM), Collins received helicopter training, as these were thought to be the best way to simulate the landing approach of the LM. After the completion of Project Gemini, it was decided to cancel the Apollo 2 flight, since it would just repeat the Apollo 1 flight. In the process of crews being reassigned, Collins was moved to the CMP position on the Apollo 8 prime crew, since his new crewmates were Borman and William Anders. Deke Slayton had decided the CMP should have some spaceflight experience, something Anders did not have. Three years later, this change would be the reason Collins orbited the Moon while Armstrong and Aldrin walked on its surface.[36]

Staff meetings were always held on Fridays in the Astronaut Office and it was here that Collins found himself on January 27, 1967. Don Gregory was running the meeting in the absence of Alan Shepard and so it was he who answered the red phone to be informed there was a fire in the Apollo 1 CM. When the enormity of the situation was ascertained, it fell on Collins to go the Chaffee household to tell Martha Chaffee her husband had died. The Astronaut Office had learned to be proactive in informing astronauts' families of a death quickly, because of the death of Theodore Freeman in an aircraft crash, when a newspaper reporter was the first to his house.[37]

Collins and David Scott were sent by NASA to the Paris Air Show in May 1967. There they met cosmonauts Pavel Belyayev and Konstantin Feoktistov, with whom they drank vodka on the Soviet's Tupolev Tu-134. Collins found it interesting that some cosmonauts were doing helicopter training like their American counterparts, and Belyayev said that he hoped to make a circum-lunar flight soon. The astronauts' wives had accompanied them on the trip, and Collins and his wife Pat were somewhat forced by NASA and their friends to travel to Metz where they had been married ten years before. There, they found a third wedding ceremony had been arranged for them (ten years previously they had already had civil and religious ceremonies).[38]

Medical problems

During 1968, Collins noticed that his legs were not working as they should, first during handball games, then as he walked down stairs, his knee would almost give way. His left leg also had unusual sensations when in hot and cold water. Reluctantly he sought medical advice and the diagnosis was a cervical disc herniation, requiring two vertebrae to be fused together.[39] The surgery was performed at Wilford Hall Hospital at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas. The planned recuperation time was three to six months.[40] He spent three months in a neck brace. It also removed Collins from the crew of Apollo 9 and moved Jim Lovell up to the prime crew. When the Apollo 8 mission was changed from a CSM/LM in Earth orbit, to a CSM-only flight around the Moon, both prime and backup crews for the Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 swapped places.[41]

Apollo 8

Having trained for the flight, Collins was made a capsule communicator (CAPCOM), an astronaut stationed at Mission Control responsible for communicating directly with the crew during a mission.[42] As part of the Green Team, he covered the launch phase up to translunar injection, the rocket burn that sent Apollo 8 to the Moon.[43] The successful completion of the first manned circum-lunar flight was followed by the announcement of the Apollo 11 crew of Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins. At that time in January 1969, it was not certain this would be the lunar landing crew, depending on the success of Apollo 9 and Apollo 10 testing the Lunar Module.[44]

Apollo 11

As CMP, Collins's training was completely different from the LM and lunar EVA, and was sometimes done without Armstrong or Aldrin being present. Along with simulators, there were size measurements for pressure suits, centrifuge training to simulate the 10 g reentry, and practicing docking with a huge rig at NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, Virginia, just to name a few. Since he would be the active participant in the rendezvous with the LM, Collins compiled a book[45] of 18 different rendezvous schemes for different scenarios including where the LM did not land, or launched too early or too late. This book ran for 117 pages.[45]

The famous mission patch of Apollo 11 was the creation of Collins. Jim Lovell, the backup commander, mentioned the idea of eagles, a symbol of the United States. Collins liked the idea and found a painting by artist Walter Weber in a National Geographic book, Water, Prey, and Game Birds of North America,[46] traced it and added the lunar surface below and Earth in the background. The idea of an olive branch, a symbol of peace, came from a computer expert at the simulators. The call sign Columbia for the CSM came from Julian Scheer, the NASA Assistant Administrator for Public Affairs. He mentioned the idea to Collins in a conversation and Collins could not think of anything better.[47] It was during the training for Apollo 11 Collins told Deke Slayton he did not want to fly again. Slayton offered to get him back into the crew sequence after the flight, and according to Collins, this would probably have been as backup commander of Apollo 14 followed by commander of Apollo 17.[48]:343

During his day flying solo around the Moon, Collins never felt lonely. Although it has been said "not since Adam has any human known such solitude",[49] Collins felt very much a part of the mission. In his autobiography he wrote "this venture has been structured for three men, and I consider my third to be as necessary as either of the other two". During the 48 minutes of each orbit he was out of radio contact with Earth, the feeling he reported was not loneliness, but rather "awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation".[50]

After spending so much time with the CSM, Collins felt compelled to leave his mark on it, so during the second night following their return from the Moon, he went to the lower equipment bay of the CM and wrote:

- "Spacecraft 107 — alias Apollo 11 — alias Columbia. The best ship to come down the line. God Bless Her. Michael Collins, CMP"[51]

In a July 2009 interview with The Guardian, Collins revealed he was very worried about Armstrong and Aldrin's safety. He was also concerned in the event of their deaths on the Moon, he would be forced to return to Earth alone and, as the mission's sole survivor, be regarded as "a marked man for life".[52]

Post-NASA activities

After being released from a 18-day quarantine, the crew embarked on a 45-day "Giant Leap" tour across the United States and around the world. Prior to this trip NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine had told Collins that Secretary of State William P. Rogers was interested in appointing Collins to the position of Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs. After the crew returned to the U.S. in November, Collins sat down with Rogers and accepted the position on the urgings of President Richard Nixon.[53] He worked in that role until Carol Laise replaced him in September 1973.[54]

Collins retired from NASA in 1970 and retired from the U.S. Air Force Reserves with the rank of Major General in 1970.[55][56][57] In 1971, Collins was appointed director of the National Air and Space Museum.[58] He held this position until 1978,[58] when he stepped down to become undersecretary of the Smithsonian Institution.[56] Collins completed the Harvard Business School's Advanced Management Program in 1974, and in 1980 became Vice President of LTV Aerospace in Arlington, Virginia. He resigned in 1985 to start his own consulting firm, Michael Collins Associates.[59]

He wrote an autobiography in 1974 entitled Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys. New York Times writer John Wilford wrote that it is "generally regarded as the best account of what it is like to be an astronaut."[60] He has also written Liftoff: The Story of America's Adventure in Space (1988), a history of the American space program, Mission to Mars (1990), a non-fiction book on human spaceflight to Mars, and Flying to the Moon and Other Strange Places (1976), revised and re-released as Flying to the Moon: An Astronaut's Story (1994), a children's book on his experiences. Along with his writing, he has painted watercolors mostly relating to his Florida Everglades home, or aircraft that he flew; they are rarely space-related.[61] Until recently he did not sign his paintings to avoid them increasing in price just because they had his autograph on them.[62]

Collins lived with his wife, Pat, in Marco Island, Florida and Avon, North Carolina until her death in April 2014.[63]

Legacy

Collins was a long-time trustee of the National Geographic Society and presently serves as Trustee Emeritus.[60] He is also a fellow of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.[21][64]

Collins was inducted into three halls of fame: the International Space Hall of Fame (1977),[9] the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame (1993),[1] and the National Aviation Hall of Fame (1985). In 2008 he was inducted into the Aerospace Walk of Honor in Lancaster, California.[65]

The International Astronomical Union honored him by naming an asteroid after him, 6471 Collins.[9] Also, like the other two Apollo 11 crew members, he has a lunar crater named after him.[66]

He was awarded the Air Force Distinguished Flying Cross in 1966 for his work in the Gemini Project.[67] Deputy Administrator Robert Seamans pinned the NASA Exceptional Service Medal on Collins and Young in 1966 for their role in the Gemini 10 mission.[68]

He was awarded Air Force Command Pilot Astronaut Wings.[21] Collins, along with the rest of the Apollo 11 crew, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Nixon in 1969 at a state dinner held in their honor.[69] The three were awarded the Collier Trophy in 1969. The National Aeronautic Association president awarded a duplicate trophy to Collins and Aldrin at a ceremony.[70][71] The trio received the international Harmon Trophy for aviators in 1970,[72][73] conferred to them by Vice President Spiro Agnew in 1971.[74] Agnew also presented them the Hubbard Medal of the National Geographic Society in 1970. He told them, "You've won a place alongside Christopher Columbus in American history".[75] He also received the Iven C. Kincheloe Award from the Society of Experimental Test Pilots (SETP) in 1970.[76][77] In 1971, Collins was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame.[78]

In 1999, while celebrating the 30th anniversary of the lunar landing, Vice President Al Gore, who was also the vice chancellor of the Smithsonian Institution's Board of Regents, presented the Apollo 11 crew with the Smithsonian's Langley Gold Medal for aviation. After the ceremony, the crew went to the White House and presented President Bill Clinton with an encased moon rock.[79][80] The crew was awarded the New Frontier Congressional Gold Medal in the Capitol Rotunda in 2011. During the ceremony, NASA administrator Charles Bolden said, "Those of us who have had the privilege to fly in space followed the trail they forged."[56][81]

Collins is one of the astronauts featured in the documentary In the Shadow of the Moon.[82] In 1989, some of his personal papers were transferred to Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.[59] He had a small part as "Old Man" in the 2009 movie, Youth in Revolt.[83]

English rock group Jethro Tull has a song "For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me", which appears on the Benefit album from 1970. The song compares the feelings of misfitting from vocalist Ian Anderson (and friend Jeffrey Hammond) with the astronaut's own, as he is left behind by the ones who had the privilege of walking on the surface of the Moon.[84] In the 1996 TV movie Apollo 11, Collins was played by Jim Metzler.[85] In the 1998 HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, he was played by Cary Elwes.[86] In the 2009 TV movie Moon Shot, he was played by Andrew Lincoln.[87] In 2013, indie pop group The Boy Least Likely To released the song "Michael Collins" on the album The Great Perhaps. The song uses Collins' feeling that he was blessed to have the type of solitude of being truly separated from all other human contact in contrast with modern society's lack of perspective.[88][89] American folk artist John Craigie recorded a song titled "Michael Collins" for his 2017 album No Rain, No Rose. The song embraces his role as an integral part of the Apollo 11 mission with the chorus, "Sometimes you take the fame, sometimes you sit back stage, but if it weren't for me them boys would still be there."[90] In the 2018 film First Man, he was portrayed by Lukas Haas.[91]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Michael Collins". Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Astronaut Fact Book" (PDF). NASA. April 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Barnes, Bart (2002-05-12). "James Collins Jr., 84; General, Military Historian". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 8–13.

- ↑ San Juan's Young King Who Climbed to the Moon. 1969 Congressional Record, Vol. 115, Pages H25639-H25640 (September 16, 1969). Accessed November 26, 2015.

- ↑ Bonner, Alice (May 10, 1977). "Ferdinand Ruge, St. Albans English Master, Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Patrick, Bethany Kelly. "Air Force Col. Michael Collins". Military.com. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Piloted the command module on Apollo 11, the first manned moon-landing mission". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Barbtree 2014, p. 184.

- ↑ Collins 2009, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Hansen 2005, pp. 346–347.

- ↑ Stark, John (July 14, 1986). "Soap Sleaze-Pot Kate Collins, An Astronaut's Daughter, Is Shooting for the Moon". People magazine. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ↑ Collins 2009, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ "1998 Distinguished Graduate Award". West Point Association of Graduates. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 13–17.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 153–155.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 25–33.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 34–40.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 40–46.

- 1 2 3 "Biographical Data" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Collins 2001, p. 77.

- ↑ Collins 2001, p. 114.

- ↑ Collins 2009, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Reichl 2016, p. 91.

- ↑ "NASA Gemini VIII First Docking Turns To Wild Ride in Orbit, Quickly Became In-Flight Emergency". Space Coast Daily. February 17, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- 1 2 Reichl 2016, p. 123.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 177–198.

- ↑ "Astronauts splash down safely; mission proves much yet to be learned in space". Palladium-Item. Richmond, Indiana. July 22, 1966. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Reichl 2016, p. 125.

- ↑ Reichl 2016, p. 126.

- ↑ Collins 2001, p. 78.

- ↑ Reichl 2016, p. 127.

- ↑ Reichl 2016, pp. 127–129.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 269–274.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 278–282.

- ↑ Skipper, Ben (July 20, 2014). "Moon Landing 45th Anniversary: Who Is Michael Collins The Forgotten Astronaut?". International Business Times. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Astronaut Gets Out of Hospital". Abilene Reporter-News. Abilene, Texas. Associated Press. July 31, 1968. p. 46 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 288–294.

- ↑ Ertel, Ivan D.; Newkirk, Roland W.; et al. (1969–1978). "Appendix 6: Crews and Support for Manned Apollo Flights". The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology. IV. Compiled by Sally D. Gates, History Office, JSC, with Cyril E. Baker, Astronaut Office, JSC. Washington, D.C.: NASA. LCCN 69060008. OCLC 23818. NASA SP-4009. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Day 1: The Green Team and Separation". Apollo Flight Journal. NASA. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ Collins 2001.

- 1 2 Collins 2001, p. 339.

- ↑ "The Making of the Apollo 11 Mission Patch". NASA. July 14, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Hansen 2005, pp. 325–332.

- ↑ Collins, Michael (2009). Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys (40th anniversary ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-53194-3.

- ↑ "July 24 Mission Logs". NASA. July 21, 1969. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ↑ Collins 2001, p. 402.

- ↑ "Michael Collins' Inscription inside Apollo 11 Command Module "Columbia"". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ McKie, Robin (July 19, 2009). "How Michael Collins became the forgotten astronaut of Apollo 11". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ Collins 2001, pp. 454–455.

- ↑ "Eyes of Nepalese". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. November 27, 1973. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Biographical Data". Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Congressional Gold Medal to Astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins. 2000 Congressional Record, Vol. 146, Page H4714 (June 20, 2000). Accessed April 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Michael Collins Fast Facts". CNN. October 26, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- 1 2 "National Air and Space Museum, Office of the Director – Agency History". Siarchives.si.edu. August 29, 2002. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "A Guide to the Michael Collins Papers 1907–1989". Ead.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- 1 2 Wilford, John Noble (July 17, 1994). "The Health Care Debate: The Astronauts". New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Michael Collins Interview". STEM in 30. Interviewed by Beth Wilson. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Michael Collins". Astronaut Central. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ↑ Marquard, Bryan (May 4, 2014). "Patricia Collins, 83; wrote about being an astronaut's wife". Boston Globe. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Fellow Classes". SETP. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ↑ "2008 Honorees". City of Lancaster. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ↑ Gaherty, Geoff (April 19, 2013). "How to See Where Astronauts Walked on the Moon". Space.com. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Michael Collins". The Hall of Valor Project. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Whoosh to Altitude Record 'Tremendous Thrill' to Astros". Independent. Long Beach, California. UPI. August 2, 1966. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ ""Three Very Brave Men" Given Presidential Toast and Medals". The Gastonia Gazette. Gastonia, North Carolina. Associated Press. August 14, 1969. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Collier 1960–1969 Recipients". National Aeronautic Association. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Apollo 11 Honor". The Burlington Free Press. Burlington, Vermont. May 7, 1970. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Two R.A.F. Pilots to Share Harmon Aviator's Trophy". New York Times. September 7, 1970. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Apollo 11 Astronauts Add Harmon Trophy to Collection". The Montgomery Advertiser. Montgomery, Alabama. Associated Press. September 6, 1970. p. 52 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "3 Astronauts get Harmon Trophies". The Times. Shreveport, Louisiana. Associated Press. May 20, 1971. p. 20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Agnew Gives Medals to Apollo 11 Crew". The La Crosse Tribune. La Crosse, Wisconsin. Associated Press. February 18, 1970. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Collins, Michael". National Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Iven C. Kincheloe Recipients". Society of Experimental Test Pilots. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Sprekelmeyer, Linda, ed. (2006). These we honor: the International Aerospace Hall of Fame. International Aerospace Hall of Fame. San Diego, California: Donning Co. Publishers. ISBN 9781578643974.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan. "Moon Anniversary Celebrated". NBC News. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Apollo 11 astronauts honored for 'astonishing' mission". CNN. July 20, 1999. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "NASA Legends Awarded Congressional Gold Medal". NASA. November 16, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ↑ Schwartz, John (September 4, 2007). "Film Takes Us Back 38 Years, to That First Walk". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ↑ Vancher, Barbara (January 8, 2010). "Michael Cera hopes that movie captures the heart of the book". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

...astronaut Michael Collins filmed a bit part as a man selling a broken-down trailer.

- ↑ Eder, Bruce. "Jethro Tull – Benefit review". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ King, Susan (November 17, 1996). "Moon Over 'Apollo 11'". The Los Angeles Times. p. 433 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ James, Caryn (April 3, 1998). "Television Review; Boyish Eyes on the Moon". The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ↑ Marill, Alvin H. (October 11, 2010). Movies Made for Television: 2005-2009. Scarecrow Press. p. 66.

- ↑ Cox, Jamieson (April 25, 2013). "The Boy Least Likely To". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Beats Per MinuteAlbum Review: The Boy Least Likely To – The Great Perhaps – Beats Per Minute". Beats Per Minute.

- ↑ Moring, JT (April 2017). "John Craigie: Millennial Storyteller". San Diego Troubadour. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Ryan Gosling's Neil Armstrong movie to open Venice Film Festival". BBC. July 19, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

Bibliography

- Barbtree, Jay (July 8, 2014). Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight. Macmillan. ISBN 9781743540657.

- Butler, Carol L. (1998). NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Biographical Data Sheet (PDF). Retrieved February 14, 2006.

- Collins, Michael (2001). Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys. Lindbergh, Charles (foreword). Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1028-X.

- Collins, Michael (2009). Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys. Lindbergh, Charles (foreword). Cooper Square Press. ISBN 9780374531942.

- Hansen, James (2005). First Man: The Life of Neil Armstrong. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5631-X.

- Reichl, Eugen (2016). Project Gemini. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer. ISBN 978-0-7643-5070-2.

- Uusma, Bea, (2003). The Man Who Went to the Far Side of the Moon: The Story of Apollo 11 Astronaut Michael Collins. ISBN 9780736227896 (Cengage Learning)

External links

- Statement From Apollo 11 Astronaut Michael Collins, NASA Public Release no. 09-164. Collins's statement on the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, July 9, 2009

- Astronautix biography of Michael Collins

- Collins at Encyclopedia of Science

- Michael Collins, David Mindell (April 1, 2015). Apollo 11's Michael Collins visits MIT/AeroAstro. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Dixon Donnelley |

Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs January 6, 1970 – April 11, 1971 |

Succeeded by Carol Laise |