Ed White (astronaut)

| Ed White | |

|---|---|

White in 1966 | |

| NASA Astronaut | |

| Nationality | American |

| Born |

Edward Higgins White II November 14, 1930 San Antonio, Texas, U.S. |

| Died |

January 27, 1967 (aged 36) Cape Kennedy, Florida, U.S. |

Resting place | West Point Cemetery |

Other occupation | Test pilot |

|

USMA, B.S. 1952 UMich, M.S. 1959 | |

| Rank |

|

Time in space | 4d 01h 56m |

| Selection | 1962 NASA Group 2 |

Total EVAs | 1 |

Total EVA time | 36 minutes |

| Missions | Gemini 4, Apollo 1 |

Mission insignia |

|

| Awards |

|

Edward Higgins White II (November 14, 1930 – January 27, 1967), (Lt Col, USAF), was an American aeronautical engineer, U.S. Air Force officer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut. On June 3, 1965, he became the first American to walk in space. White died along with astronauts Virgil "Gus" Grissom and Roger B. Chaffee during prelaunch testing for the first manned Apollo mission at Cape Canaveral. He was awarded the NASA Distinguished Service Medal for his flight in Gemini 4 and then awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor posthumously.

Biography

Early years, education and military service

White was born on November 14, 1930, in San Antonio, Texas, to parents Edward Higgins White Sr. (1901–1978), who became a major general in the U.S. Air Force, and Mary Rosina White (née Haller; 1900–1983).[1] He attended school in his hometown and became a member of the Boy Scouts of America,[2] where he earned the rank of Second Class Scout.[3] After graduation from high school in 1948, he was accepted to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where in 1952 he earned his Bachelor of Science degree and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Air Force.[4] Then, he attended flight school, a course that takes just over a year. Following graduation from flight school in 1953, White was assigned to the 22nd Fighter Day Squadron at Bitburg Air Base, West Germany. He spent three and a half years in West Germany flying in F-86 Sabre and F-100 Super Sabre squadrons in the defense of NATO.[5][6]

After graduating from West Point, White competed for a spot on the U.S. Olympic team in the 400 meter hurdles race.[7] He missed making the team by only 1/10 second. His hobbies included squash, handball, swimming, golf, and photography.[8]

In 1958, White enrolled in the University of Michigan under Air Force sponsorship to study Aeronautical Engineering, where he received his Master of Science degree in 1959. Following graduation, White was selected to attend the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California. He earned his credentials as a test pilot in 1959 and was assigned to the Aeronautical Systems Division at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.[8] During his career, White would log more than 3,000 flight hours with the Air Force, including about 2,200 hours in jets, and would ultimately attain the rank of lieutenant colonel.[5]

In 1953, White married Patricia Finegan, whom he met while at West Point.[6] The Whites would have two children, Edward White III (born September 16, 1953) and Bonnie Lynn White (born May 15, 1956). White was a devout Methodist.[9]

NASA career

Project Gemini

White was one of nine men chosen as part of the second group of astronauts in 1962. Within an already elite group, White was considered to be a high-flier by the management of NASA. He was chosen as Pilot of Gemini 4, with Command Pilot James McDivitt. White became the first American to make a walk in space, on June 3, 1965. He found the experience so exhilarating that he was reluctant to terminate the EVA at the allotted time, and had to be ordered back into the spacecraft. While he was outside, a spare thermal glove floated away through the open hatch of the spacecraft, becoming an early piece of space debris in low Earth orbit, until it burned up upon re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. There was a mechanical problem with the hatch mechanism, which made it difficult to open and to relatch, which added to the time constraint of the spacewalk, and could have threatened the lives of both men if McDivitt had been unable to get the hatch latched, as they could not re-enter the atmosphere with an unsealed hatch.

I'm coming back in... and it's the saddest moment of my life.

White's next assignment after Gemini 4 was as the backup for Gemini 7 Command Pilot Frank Borman. He was also named the astronaut specialist for the flight control systems of the Apollo Command/Service Module. By the usual procedure of crew rotation in the Gemini program, White would have been in line for a second flight as the command pilot of Gemini 10 in July 1966, which would have made him the first of his group to fly twice.

Apollo program

In March 1966 he was selected as senior pilot (second seat) for the first manned Apollo flight, designated AS-204, along with Command Pilot Virgil "Gus" Grissom, who had flown in space on the Mercury 4 Liberty Bell 7 mission and as commander of the Gemini 3 Molly Brown mission, and Pilot Roger Chaffee, who had yet to fly into space. The mission, which the men named Apollo 1 in June, was originally planned for late 1966 (perhaps concurrent with the last Gemini mission), but delays in the spacecraft development pushed the launch into 1967.

Death

The launch of Apollo 1 was planned for February 21, 1967. The crew entered the spacecraft on January 27, mounted atop its Saturn IB booster on Launch Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy, for a "plugs-out" test of the spacecraft, which included a rehearsal of the launch countdown procedure. Midway through the test, a fire broke out in the pure oxygen-filled cabin, killing all three men.

White's job was to open the hatch cover in an emergency, which he apparently tried to do; his body was found in his center seat, with his arms reaching over his head toward the hatch. Removing the cover to open the hatch was impossible, because the plug door design required venting normally slightly greater-than-atmospheric pressure and pulling the cover into the cabin. Grissom was unable to reach the cabin vent control to his left, where the fire's source was located. The intense heat raised the cabin pressure even more, to the point where the cabin walls ruptured. The astronauts were killed by asphyxiation and smoke inhalation.

The fire's ignition source was determined to be a spark that jumped from a wire on the far left of the spacecraft, under Grissom's seat,[11] but their deaths were attributed to a wide range of lethal hazards in the early Apollo Command Module design and workmanship and conditions of the test, including the highly pressurized 100% oxygen pre-launch atmosphere, many wiring and plumbing flaws, flammable materials used in the cockpit and the astronauts' flight suits, and a hatch which could not be quickly opened in an emergency.[12] After the incident, these problems were fixed, and the Apollo program carried on successfully to reach its objective of landing men on the Moon.

White was buried with full military honors at West Point Cemetery while Grissom and Chaffee are both buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[13]

In 1997, White was posthumously awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor. White was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1993[14] and the National Aviation Hall of Fame on July 18, 2009.[15][16]

White's wife Patricia remarried and continued to reside in Houston. On September 7, 1983, she committed suicide after surgery earlier in the year to remove a tumor.[17][18]

Organizations

He was a member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots; associate member of Institute of Aerospace Sciences; Tau Delta Phi (Engineering Honorary); and Sigma Delta Psi (Athletic Honorary).[5]

Awards and honors

- Senior Astronaut Wings[5]

- Air Force Commendation Medal[14]

- Congressional Space Medal of Honor (posthumous)[19]

- NASA Exceptional Service Medal[5]

- Golden Plate Award for Science and Exploration, 1965[20]

- Medalha Bandeirantes va Cosmonautica[5]

- Firefly Club Award[5]

- Ten Outstanding Young Men of the Nation, 1965[5]

- Five Outstanding Young Texans, 1965[5]

- Harmon Trophy, 1966

- Arnold Air Society's John F. Kennedy Trophy[5]

- Aerospace Primus Club[5]

- National Aviation Club's Achievement Award, 1966[5]

- Inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame, 1969[19]

- General Thomas D. White National Defense Award[5]

- Honorary Doctorate degree in Astronautics, University of Michigan[5]

Memorials

Schools

Many schools have been named in honor of Lt Colonel White:

- Edward White Elementary Career Academy in Chicago.[21]

- Edward H. White Middle School in White's hometown of San Antonio, Texas.[22]

- Edward H. White II Elementary School in El Lago, Texas.[23][24]

- Edward White Elementary School in Eldridge, Iowa.[25]

- Ed White Memorial High School in League City, Texas.[26]

- Edward H. White High School in Jacksonville, Florida.[27]

- Edward H. White Elementary School in Houston, Texas.[28]

- Ed White Middle School in Huntsville, Alabama.[29] Huntsville is home to NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and has strong community ties to the space program. At the same time, the Huntsville City Schools named Roger B. Chaffee Elementary School and Virgil I. Grissom High School for White's fallen Apollo 1 crewmates.[30]

- Edward H. White Memorial Youth Center, Seabrook, Texas[31]

Other sites

- Edward White Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida (closed in 2014)[32]

- Edward H. White II Park in Fullerton, California. Fullerton has also named parks in honor of Chaffee and Grissom.[33]

- Island White, an artificial island in Long Beach Harbor off Southern California.[34][35]

- Edward H. White Hall was a dormitory at Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, Texas.[36] White Hall housed the 365th Training Squadron until 2010. The 365th trains aircraft avionics technicians.

- McDivitt-White Plaza is located outside West Hall at the University of Michigan. West Hall formerly housed the College of Engineering and counts James McDivitt and Ed White among its alumni (McDivitt earned his B.S. and White earned his M.S. at the University of Michigan).[37]

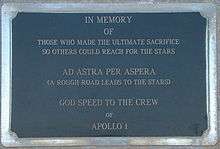

- The dismantled Launch Pad 34 at Cape Canaveral bears two memorial plaques. One reads, "They gave their lives in service to their country in the ongoing exploration of humankind's final frontier. Remember them not for how they died but for those ideals for which they lived." and the other "In memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice so others could reach for the stars. Ad astra per aspera, (a rough road leads to the stars). God speed to the crew of Apollo 1."[6]

- Edward H. White II American Legion Post 521; Pasadena, Texas.[38]

In space

- The star Iota Ursae Majoris was nicknamed "Dnoces" ("Second", as in "Edward Higgins White the Second", spelled backwards).[39]

- White Hill, 11.2 km (7.0 mi) northwest of Columbia Memorial Station on Mars, is a part of the Apollo 1 Hills.[40]

- A photograph of White performing his Gemini 4 space walk is included as one of several images on the Voyager Golden Record.[41]

Philatelic

- Eight months after his death, in September 1967, a postage stamp was issued by the United States Post Office, commemorating White's spacewalk, the first-ever by an American.[42] It was the first time in USPO history that the design was actually spread over two stamps (one which featured White, the other his Gemini capsule, the two connected by a tether), which was considered befitting the "twins" aspect of the Gemini mission.[30]

Omega Speedmaster "Ed White"

The Omega Speedmaster wristwatch reference 105.003 has come to be known as the "Ed White" as this reference was worn by White during his spacewalk. The Speedmaster remains the only watch qualified by NASA for EVA use.

In media

White was played by Steven Ruge in the 1995 film Apollo 13, by Chris Isaak in the 1998 HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, and by Matt Lanter in the 2015 ABC TV series The Astronaut Wives Club.[43][44] In 2018, he will be portrayed by Jason Clarke in First Man.[45]

See also

- Alexey Leonov - first man to conduct a spacewalk

- Fallen Astronaut

- List of spaceflight-related accidents and incidents

- Voskhod 2 - Soviet space mission which included the first spacewalk

- Accomplishments in Space Commemorative stamp

References

- ↑ Edward Higgins White II at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Astronauts and the BSA". Fact sheet. Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved March 20, 2006.

- ↑ Edward Higgins White at scouting.org Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Prior to the first graduating class from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1959, a certain percentage of officers in the U.S. Air Force were drawn from West Point and from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. In any case, the vast majority of officers in the U.S. Armed Forces are educated and trained at the three kinds of R.O.T.C. programs at hundreds of other institutes and universities across the country.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Astronaut Bio: Edward H. White II". NASA. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- 1 2 3 "The Official Site of Edward White II". Cmgww.com. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ↑ White, Mary. "Detailed Biographies of Apollo I Crew - Ed White". NASA.

- 1 2 White, Mary C. "Detailed Biographies of Apollo I Crew - Ed White". NASA. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ↑ Burgess, Colin and Doolan, Kate, with Vis, Bert (2003). Fallen Astronauts: Heroes Who Died Reaching for the Moon, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6212-4

- ↑ Composite Air-to-ground and Onboard Voice Tape Transcription of the GT-4 Mission (U) (PDF), NASA, 31 August 1965, p. 54

- ↑ Kluger, Jeffrey, Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon (Henry Holt & Co., 2017), p. 94. "At precisely 6:31 p.m., a spark jumped from a wire on the far left of the spacecraft, beneath Gus Grissom's seat. The wire ran beneath a little storage compartment with a metal door that had been opened and closed many times without anybody noticing that each time the door moved, it abraded a little more of the wire's insulation, finally leaving the wire free to spark at will. When the wire sparked during the plugs-out test, it ignited a small fire that stayed small for only a second or two. Accelerated by the pure oxygen, the flames climbed along the left-hand wall of the spacecraft, feeding on fabric and netting used for storage. That was the worst possible place for a fire to erupt, since it presented Grissom from reaching a latch that would have opened a valve and vented the high-pressure atmosphere, thus slowing the flames."

- ↑ "Findings, Determinations And Recommendations". Report of Apollo 204 Review Board. NASA. April 5, 1967.

No single ignition source of the fire was conclusively identified.

- ↑ "West Point Cemetery" (PDF). United States Military Academy West Point. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- 1 2 Ed White inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame

- ↑ Kaplan, Ron (December 17, 2008). "National Aviation Hall of Fame reveals names of "Class of 2009" inductees". National Aviation Hall of Fame web site. National Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ↑ Hannah, James (July 19, 2009). "Ed White, Jimmy Stewart inducted in Aviation Hall". Washington Post.

- ↑ UPI (1983-09-08). "Pat White's obituary in New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ↑ "PBS's "Race to the Moon" site on Pat White's suicide". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- 1 2 "The First American to walk in space". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Ellis, Lee (2004). Who's Who of NASA Astronauts. Americana Group Publishing. p. 424.

- ↑ "Edward White Elementary Career Academy". Chicago Public Schools. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Edward H. White Middle School". San Antonio, Texas: North East Independent School District. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Ed White Elementary School". Clear Creek ISD. Archived from the original on August 11, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

Our school opened in 1965 as El Lago Elementary. The name was changed in 1967 to Edward H. White II Elementary in honor of the life and accomplishments of Edward Higgins White II -- the first American to walk in space.

- ↑ "Ed H. White Elementary". Clear Creek Independent School District. Archived from the original on April 1, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ↑ "North Scott Community School District". Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Bay Area Charter Schools". Archived from the original on July 12, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Edward H. White". Duval County Public Schools. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ "History of Ed White". Ed White Elementary. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Ed White Middle School". Huntsville (Ala.) City Schools official site.

- 1 2 Jaques, Bob (June 6, 2002). "First spacewalk by American astronaut 37 years ago" (PDF). Marshall Star. NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. p. 5.

- ↑ "Ed White Memorial Youth Center". Ed White Memorial Youth Center. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Hospital Closure". HCA West Florida. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "City of Fullerton - List of Parks". Ci.fullerton.ca.us. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ↑ Michael Robert Patterson. "Fallen Astronaut". Arlingtoncemetery.net. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ↑ "pdf of City of Long Beach Economic Zones". Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the 82d Training Wing and Sheppard AFB" (PDF). Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Vielmetti, Edward (May 25, 2010). "Our neighborhoods: South University as seen from McDivitt-White Plaza". The Ann Arbor News. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Post History". American Legion Post 521. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Apollo 15 Lunar Surface Journal". NASA. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Martian Landmarks Dedicated to Apollo 1 Crew". NASA. January 27, 2004. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Here's What Humanity Wanted Aliens to Know About Us in 1977". Time. January 22, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Gemini Space Walk". Sky Image Lab. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ James, Caryn (April 3, 1998). "Television Review; Boyish Eyes on the Moon". The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ↑ "The Astronaut Wives Club: Full Cast and Crew". IMDb. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ↑ "First Man: Full Cast and Crew". IMDb. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Higgins White. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edward Higgins White |

- Official website of Edward White II

- Ed White on IMDb

- Congressional Space Medal of Honor, C-SPAN, December 17, 1997

- Unknown author. "Edward Higgins White, II". NASA.