Gene Cernan

| Gene Cernan | |

|---|---|

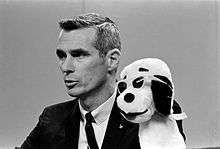

Cernan in December 1971  | |

| NASA Astronaut | |

| Nationality | American |

| Born |

Eugene Andrew Cernan March 14, 1934 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died |

January 16, 2017 (aged 82) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

Resting place | Texas State Cemetery |

Other occupation | Naval aviator, fighter pilot |

|

Purdue University, B.S. 1956 NPS, M.S. 1963 | |

| Rank |

|

Time in space | 23d 14h 15m |

| Selection | 1963 NASA Group 3 |

Total EVAs | 4 |

Total EVA time | 24 hours 11 minutes |

| Missions | Gemini 9A, Apollo 10, Apollo 17 |

Mission insignia |

|

| Retirement | July 1, 1976 |

| Awards |

|

| Website |

genecernan |

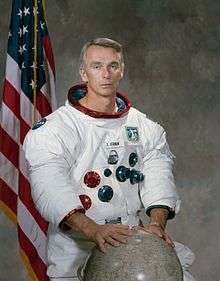

Eugene Andrew Cernan (/ˈsɜːrnən/; March 14, 1934 – January 16, 2017) was an American astronaut, naval aviator, electrical engineer, aeronautical engineer, and fighter pilot. During the Apollo 17 mission, Cernan became the eleventh person to walk on the Moon. Since he re-entered the lunar module after Harrison Schmitt on their third and final lunar excursion, he was the last person to have walked on the Moon.

Cernan traveled into space three times; as pilot of Gemini 9A in June 1966, as lunar module pilot of Apollo 10 in May 1969, and as commander of Apollo 17 in December 1972, the final Apollo lunar landing. Cernan was also a backup crew member of the Gemini 12, Apollo 7 and Apollo 14 space missions.

Biography

Early years

Cernan was born on March 14, 1934, in Chicago, Illinois; he was the son of Rose (née Cihlar) and Andrew Cernan. His father was of Slovak descent and his mother was of Czech ancestry.[1][2] Cernan grew up in the Illinois towns Bellwood and Maywood. He was a Boy Scout and earned the rank of Second Class.[3] After attending McKinley Elementary School in Bellwood and graduating from Proviso East High School in Maywood in 1952, he studied at Purdue University, where he became a member of Phi Gamma Delta fraternity. After his sophomore year, he accepted a partial Navy ROTC scholarship that required him to serve aboard USS Roanoke between his junior and senior years. In 1956, he received a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering; his final GPA was 5.1 out of 6.0.[4]

Cernan's hobbies included love for horses, sports, hunting, fishing, and aviation.[5]

Navy service

Cernan was commissioned a U.S. Navy Ensign through the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps at Purdue, and was initially stationed on the USS Saipan. Cernan changed to active duty and attended flying training at Whiting Field, Baron Field, Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, and Naval Air Station Memphis.[6]:29–31 Following flight training on the T-28 Trojan, T-33 Shooting Star, and F9F Panther, Cernan became a Naval Aviator, flying FJ-4 Fury and A-4 Skyhawk jets in Attack Squadrons 126 and 113.[6]:31–33,38–39 Upon completion of his assignment in Miramar, California, he finished his education in 1963 at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School with a Master of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering.[5]

During his naval career, Cernan logged more than 5,000 hours of flying time, including 4,800 hours in jet aircraft. Cernan also made 200 landings on aircraft carriers.[5]

NASA career

In October 1963, NASA selected Cernan as one of the third group of astronauts to participate in the Gemini and Apollo space programs.[5]

Gemini program

Cernan was originally selected with Thomas Stafford as backup pilot for Gemini 9. When the prime crew of Elliot See and Charles Bassett was killed in the crash of NASA T-38A "901" (USAF serial 63-8181) at Lambert Field on February 28, 1966, the backup crew became the prime crew—the first time in NASA history this happened.[7] Gemini 9A encountered a number of problems; the original target vehicle exploded during launch and the planned docking with a substitute target vehicle was made impossible by the failure of a protective shroud to separate after launch.[7] The crew, however, performed a rendezvous that simulated procedures that would be used in the Apollo 10 mission; the first optical rendezvous and a lunar-orbit-abort rendezvous. Cernan performed the second American EVA—the third-ever spacewalk—but overexertion caused by a lack of limb restraints prevented testing of the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit and forced the early termination of the spacewalk.[7] Cernan was also a backup pilot for the Gemini 12 mission.[8]

Apollo program

Apollo 10

Cernan was selected for the lunar module pilot position on the backup crew for Apollo 7—although that flight carried no lunar module.[9] Standard crew rotation put him in place as the Lunar Module Pilot on Apollo 10—the final dress rehearsal mission for the first Apollo lunar landing—on May 18–26, 1969. During the Apollo 10 mission, Cernan and his commander, Tom Stafford, piloted the Lunar Module Snoopy in lunar orbit to within 8.5 nautical miles (15.7 km) of the lunar surface, successfully executing every phase of a lunar landing up to final powered descent and providing NASA planners with critical knowledge of technical systems and lunar gravitational conditions to enable Apollo 11 to land on the Moon two months later.

Apollo 17

Cernan turned down the opportunity to walk on the Moon as Lunar Module Pilot of Apollo 16, preferring to risk missing a flight for the opportunity to command his own mission.[10] Cernan moved back into the Apollo rotation as commander of the backup crew of Cernan, Ronald E. Evans, and Joe Engle for Apollo 14, putting him in position through normal crew rotation to command his own crew on Apollo 17. Escalating budget cutbacks for NASA, however, brought the number future lunar missions into question. After the cancellation of Apollo 15 in its original H class profile and Apollo 19 in September 1970, pressure from the scientific community to shift Harrison Schmitt, the sole professional geologist in the active Apollo roster of astronauts, to the crew of Apollo 17, the final scheduled Apollo mission, mounted. In August 1971, NASA named Schmitt as the lunar module pilot for Apollo 17, which meant the original LM pilot Joe Engle never had the opportunity to walk on the Moon. Cernan fought to keep his crew together; given the choice of flying with Schmitt as LMP or seeing his entire crew removed from Apollo 17, Cernan chose to fly with Schmitt. Cernan eventually came to have a positive evaluation of Schmitt's abilities; he concluded that Schmitt was an outstanding LM pilot while Engle—notwithstanding his outstanding record as an aircraft test pilot—was merely an adequate one.[11]

Cernan's role as commander of Apollo 17 closed out the Apollo program's lunar exploration mission with a number of record-setting achievements. During the three days of Apollo 17's surface activity (Dec. 11-14, 1972), Cernan and Schmitt performed three EVAs for a total of about 22 hours of exploration of the Taurus–Littrow valley. Their first EVA alone was more than three times the length astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin spent outside the LM on Apollo 11. During this time Cernan and Schmitt covered more than 35 km (22 mi) using the Lunar Rover and spent a great deal of time collecting geologic samples (including a record 34 kilograms (75 lb) of samples, the most of any Apollo mission) that would shed light on the Moon's early history. Cernan piloted the rover on its final sortie, recording a maximum speed of 11.2 mph (18.0 km/h), giving him the unofficial lunar land speed record.[12]

As Cernan prepared to climb the ladder for the final time, he spoke these words, currently the last spoken by a human being standing on the lunar surface:

Bob, this is Gene, and I'm on the surface; and, as I take man's last step from the surface, back home for some time to come – but we believe not too long into the future – I'd like to just (say) what I believe history will record: that America's challenge of today has forged man's destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus–Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.

— Cernan, [13]

Cernan's status as the last person to walk on the Moon means Purdue University is the alma mater of both the first person to walk on the Moon—Neil Armstrong—and the most recent. Cernan is one of only three astronauts to travel to the Moon on two occasions; the others being Jim Lovell and John Young. As of 2018, he is also one of only twelve people to have walked on the Moon. Apollo 10 holds the record for the highest speed attained by any manned vehicle at 39,897 km/h (24,791 mph) during its return from the Moon on May 26, 1969.[8]

Post-NASA career

.jpg)

In 1976, Cernan retired from the Navy with the rank of captain and went from NASA into private business, becoming Executive Vice President of Coral Petroleum Inc. before starting his own company, The Cernan Corporation, in 1981.[5] From 1987 he was a contributor to ABC News and the weekly segment of its Good Morning America program titled "Breakthrough", which covered health, science, and medicine.[14]

In 1999, with co-author Donald A. Davis, he published his memoir The Last Man on the Moon, which is about his naval and NASA career. He is featured in the space exploration documentary In the Shadow of the Moon. in which he said, "truth needs no defense" and "nobody can take those footsteps I made on the surface of the Moon away from me".[15] Cernan also contributed to the book of the same name.

Cernan and Neil Armstrong testified before U.S. Congress in 2010 in opposition to the cancellation of the Constellation program, which had been initiated during the George W. Bush administration as part of the Vision for Space Exploration with the aim of returning humans to the Moon and eventually Mars, but was deemed underfunded and unsustainable by the Augustine Commission in 2009.[16]

Cernan paired his criticism of the cancellation of Constellation with expressions of skepticism about Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) and Commercial Crew Development (CCDev), NASA's planned replacements for that program's role in supplying cargo and crew to the International Space Station. Such companies, Cernan warned, "do not yet know what they don't know." Cernan's view of commercial space companies—in particular SpaceX, which participates in both programs—underwent a positive shift after being debriefed by SpaceX venture capitalist Steve Jurvetson as part of his effort to obtain the signatures of nine Apollo astronauts on a photograph meant as a gift to SpaceX founder Elon Musk to commemorate the first successful SpaceX cargo mission to the ISS in 2012. Eventually, Cernan was won over and signed the photograph; "As I told him these stories of heroic entrepreneurship, I could see his mind turning." Jurvetson wrote; "He found a reconciliation: 'I never read any of this in the news. Why doesn't the press report on this?'" [17]

In 2016, Cernan appeared in the documentary The Last Man on the Moon, made by British filmmaker Mark Craig and based on Cernan's 1999 memoir of the same title.[18] The film received the Texas Independent Film Award from Houston Film Critics Society and the Movies for Grownups Award from AARP The Magazine.[19][20]

Personal life

Cernan was married twice and had one daughter. His first wife was Barbara Jean Atchley, a flight attendant for Continental Airlines whom he married in 1961. They had one daughter, Tracy (born in 1963). The couple separated In 1980 and divorced in 1981. They remained friends.[21] His second marriage was to Jan Nanna Cernan, which lasted for nearly 30 years from 1987 until his death. Cernan gained two step-daughters, Kelly and Danielle.[22]

Death

| Wikinews has related news: Former NASA astronaut Eugene Cernan dies aged 82 |

Cernan died in a hospital in Houston on January 16, 2017, at the age of 82.[23] His funeral was held at St. Martin's Episcopal Church in Houston.[24] He was buried with full military honors at Texas State Cemetery—the first astronaut to be buried there—during a private service on January 25, 2017.[25][26]

Organizations

Cernan was a member of several organizations: Fellow, American Astronautical Society; member, Society of Experimental Test Pilots; member, Tau Beta Pi (National Engineering Society), Sigma Xi (National Science Research Society), Phi Gamma Delta (National Social Fraternity), and The Explorers Club.[5]

Awards and honors

- Naval Aviator Astronaut Insignia[5]

- Navy Distinguished Service Medal, Gold star device in lieu of second award[5]

- Distinguished Flying Cross[5]

- National Defense Service Medal

- NASA Distinguished Service Medal[5]

- NASA Exceptional Service Medal[5]

- Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy, 2007[27]

- International Space Hall of Fame[8]

- U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame[28]

- Great American Award, The All-American Boys Chorus, 2014[30]

- Cernan was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum in 2007.[31]

- Orbital ATK announced the naming of its Cygnus CRS OA-8E Cargo Delivery Spacecraft the S.S. Gene Cernan in honor of Cernan in October, 2017.[32] The S.S. Gene Cernan successfully launched to the International Space Station on November 12, 2017.[33]

In popular culture

On July 2, 1974, Cernan was a roaster of Don Rickles on The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast. At the end of the roast, Rickles—who attended the Apollo 17 launch—paid tribute to Cernan as a "delightful, wonderful, great hero".[34] Cernan was featured in the Discovery Channel's documentary miniseries When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions, talking about his involvement and missions as an astronaut.[35] In the 1998 Primetime Emmy Award-winning HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, he was portrayed by Daniel Hugh Kelly.[36]

A popular belief is that Cernan wrote his daughter's initials on a rock on the Moon. The story, and Cernan's relationship with his daughter, was later adapted into "Tracy's Song" by pop-rock band No More Kings. The story is inaccurate; Cernan did not write his daughter's initials on a rock. He states in the 2014 documentary The Last Man on the Moon that he wrote them in the lunar dust as he left the rover to return to the LEM and Earth.[37] The true story of leaving the initials on the lunar surface was prominently mentioned in an episode (Season 3 Episode 20: The Last Walt) of Modern Family.[38]

A recording of Cernan's voice during the Apollo 17 mission was sampled by Daft Punk for "Contact", the last track on their 2013 album Random Access Memories.[39] Cernan's last words from the lunar surface, along with Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt's recollections, were used by the band Public Service Broadcasting for the song Tomorrow, the final track of their 2015 album The Race for Space.[40]

See also

- List of spaceflight records

- Cernan Earth and Space Center, a public planetarium on the campus of Triton College in River Grove, Illinois named in Cernan's honor.

References

- ↑ Evans, Ben (April 2, 2010). "Escaping the Bonds of Earth: The Fifties and the Sixties". Springer Science & Business Media. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "United States Census, 1940". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Scouting and Space Exploration". Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Gene Cernan: Always Shoot for the Moon, Part I". Airport Journals. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Biographical Data". Johnson Space Center. December 1994. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- 1 2 Cernan, Eugene; Davis, Don (March 15, 1999). The Last Man On The Moon. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-19906-7.

- 1 2 3 Hacker, Barton C.; Grimwood, James M. (September 1974). "Chapter 14 Charting New Space Lanes". On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. NASA History Series. SP-4203. NASA. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Commanded Apollo 17, the last manned lunar mission". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Apollo 7 Crew - National Air and Space Museum". airandspace.si.edu. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Gene Cernan Oral History". Houston Oral History Project. February 5, 2009. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ↑ "A Running Start - Apollo 17 up to Powered Descent Initiation". Apollo 17 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. June 10, 2014. Archived from the original on July 12, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ Lyons, Pete (January 1988). "10 Best Ahead-of-Their-Time Machines". Car and Driver. p. 78.

- ↑ Jones, Eric M (October 28, 2010). "EVA-3 Close-out". Apollo 17 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on October 28, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ↑ "'Good Morning' Segment For Cernan". Los Angeles Times. January 8, 1987. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ Soller, Kurt (July 17, 2009), "Moonstruck: Debunking the Claims of Moon Landing Deniers", Newsweek, archived from the original on August 25, 2009, retrieved September 4, 2009

- ↑ "Armstrong: Obama NASA Plan 'devastating'". NBC News. April 13, 2010. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Apollo astronauts, SpaceX, and a special photo". Space Politics. July 12, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ↑ Heithaus, Harriet Howard. "Mark Craig, moonwalk film director, recalls it". Naples Daily News. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ↑ "AARP Movies for Grown Ups Award". The Last Man on the Moon. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Houston Film Critics Award". The Last Man on the Moon. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Astronaut Eugene Cernan's regrets after being the last man to walk on the Moon". Mirror. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Ervin, Jeremy (January 16, 2017). "Astronaut, Purdue grad Gene Cernan dead at 82". Journal and Courier. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Remembering Gene Cernan". NASA. January 16, 2017. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Hundreds attend Gene Cernan's funeral". KHOU. January 24, 2017.

- ↑ Flores, Nancy (January 17, 2017). "Astronaut Gene Cernan to be buried at Texas State Cemetery". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Newton, Noelle. "Former Astronaut Gene Cernan buried at State Cemetery". Fox News. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Wright Bros. 2000-2009 Recipients". National Aeronautic Association. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame". Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. Archived from the original on October 15, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ↑ Slovak republic website, State honours Archived April 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. : 2nd Class (click on "Holders of the Order of the 2nd Class White Double Cross" to see the holders' table)

- ↑ Graham, Jordan (November 4, 2014). "Moon's last visitor comes to town". The Orange Country Register. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Mourning the loss of Gene Cernan". Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ "S.S. Gene Cernan Fact Sheet" (PDF). Orbital ATK Newsroom. Orbital ATK. October 21, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Orbital ATK Successfully Launches Eighth Cargo Delivery Mission to the International Space Station". Orbital ATK News Room. Orbital ATK. November 12, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Don Rickles". Dean Martin Celebrity Roast. Season 1. Episode 17. February 7, 1974. NBC.

- ↑ Schwartz, John (June 6, 2008). "50 Years of NASA's Home Movies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ↑ James, Caryn (April 3, 1998). "Television Review; Boyish Eyes on the Moon". The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Last Man on Moon Left Camera Behind, Regrets NASA's Fade". Bloomberg. December 4, 2012. Archived from the original on June 22, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ "The Last Walt". Modern Family. Season 3. Episode 20. April 18, 2012. 16:45 minutes in. ABC.

When he was leaving the Moon he reached down and wrote his daughter's initials into the lunar surface.

- ↑ "Watch DJ Falcon discuss new Daft Punk album, sampling NASA space missions". Consequence of Sound. May 7, 2013. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Public Service Broadcasting - The Race For Space". therevue.ca. February 15, 2015. Archived from the original on September 2, 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gene Cernan |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eugene A. Cernan. |