Menno van Coehoorn

| Menno, Baron van Coehoorn | |

|---|---|

Menno, Baron van Coehoorn. | |

| Born |

March, 1641 Britsum, Friesland, Dutch Republic |

| Died |

17 March 1704 (aged 62–63) The Hague |

| Buried | Wijkel |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ | Infantry, then Engineers |

| Years of service | 1657 – 1704 |

| Rank |

Lieutenant General Ingenieur Generaal der Fortificatiën General of Artillery |

| Commands held |

Garrison Commander Namur 1692 Zeelandic Flanders 1702 |

| Battles/wars |

Second Anglo-Dutch War Franco-Dutch War; Siege of Maastricht (1673) Siege of Grave 1674 Seneffe 1674 Battle of Cassel (1677) Battle of Saint-Denis (1678) Nine Years' War; Fleurus (1690) Siege of Namur (1692) Siege of Namur (1695) War of the Spanish Succession Sieges of Venlo and Roermond 1702 |

Menno, Baron van Coehoorn (March 1641 – 17 March 1704) was a Dutch soldier and engineer regarded as one of the most significant figures in Dutch military history. During his lifetime, he and his French counterpart Vauban were the acknowledged experts in siege warfare and the design of fortifications.

Life

Van Coehoorn was born in March 1641, one of six sons of Goosewijn van Coehoorn and Aaltje van Hinckena on the Lettinga State in the village of Britsum near Leeuwarden in the Dutch province of Friesland. His father was an officer of German descent in a Friesland regiment of the Dutch States Army and a member of the petty nobility.

Menno was educated at home with his brothers, then later at the University of Franeker by his uncle Bernardus Fullenius, where he showed a talent for mathematics and military drawing.[1] In 1657, he was commissioned as a Lieutenant in his father's company,[lower-alpha 1] which formed part of the permanent garrison in Maastricht.[2]

In 1678, Van Coehoorn married Magdalena van Scheltinga; they had four surviving children, Goosewijn (1678-1737), Gertruda (1679-1757), Hendrik (1683-1756) and Amalia (1683-1708). Magdalena died in 1683 and he later married Truytje van Wigara (dates unknown). He died on 17 March 1704.[3]

Early career

Promoted Captain in October 1660 by the Frisian stadtholder William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz, Van Coehoorn first saw action in 1665 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War when he helped repulse an English-funded invasion by the Bishop of Munster. During the Franco-Dutch War of 1672-78, he was wounded at the unsuccessful defense of Maastricht in 1673, then fought at Grave and Seneffe in 1674. He was promoted Major by Henry Casimir II, Prince of Nassau-Dietz, took part in the battles of Cassel and Saint-Denis and ended the war as a Lieutenant-Colonel.[1]

In the Netherlands, 1672 is still referred to as the Rampjaar or Year of Disaster. The rapid fall of major fortresses like Nijmegen and Fort Crèvecœur near 's-Hertogenbosch demonstrated the Republic's vulnerability and the obsolescence of its defences. This caused intense debate in two areas; first, where to locate defenses, which led to the concept of 'Barrier Fortresses' and ultimately the Barrier Treaties.[4] The second was how to design fortifications that could withstand a long siege in the flat terrain of the Netherlands.

Design Principles

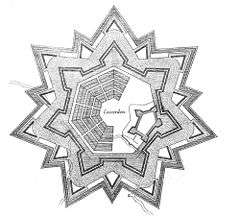

Van Coehoorn formulated his ideas in a public debate over the design of a new fortress at Coevorden with Captain Louis Paen, a fellow officer who in 1679 produced a well-received critique of the Dutch drill manual.[5] This resulted in the 1682 publication of Van Coehoorn's Versterckinge des Vijfhoeks met al syne buytenwerken or Fortification of the Pentagon and all its outer works, followed in 1685 by his best-known work Nieuwe Vestingbouw op een natte of lage horisont or New Fortress Construction on a Wet or Low Horizon.[1]

Since maintaining a large standing army was too expensive for most states, the purpose of permanent fortifications was to provide time to mobilise forces.[6] The Dutch were nearly overrun in 1672 by the speed with which fortresses like Nijmegen and Fort Crèvecœur near 's-Hertogenbosch fell,[lower-alpha 2] being saved only by the desperate measure of activating the Hollandic Water Line. Van Coehoorn's approach accepted that the flat terrain of the Netherlands and huge cost of construction meant an effective defence could not rely solely on fortifications. His designs included the following principles;

Active defence; defenders would constantly disrupt the besiegers rather than simply sitting behind their walls.[7] This in turn required the provision of open areas within the fortifications to assemble a counter-attacking force.

Multiple defence lines; the existing practice of all round defence meant a breach in one area often led to the rapid surrender of the whole position. Instead, Van Coehoorn created multiple 'Inner' and 'Outer' defence zones that funnelled attackers through successive 'killing zones' of flanking fire; [lower-alpha 3]

Denial of terrain; "... he protected his works by digging alternate ranks of wet and dry ditches. The dry ditches and covertways were cut down to within a few inches of the water table ... (if the besiegers) cut into the floor in the normal way, they would soon be flooded out;"[9]

Van Coehoorn claimed his methods used two-thirds of the materials required for similar French fortifications, although this was largely because the high water table common in the Netherlands made the danger of mining academic.[10] [lower-alpha 4]

Another feature of his defensive works was the use of inundations or water where possible. Although not completed until years after his death, Van Coehoorn designed the Zuider Waterlinie, which ran from Sluis along North Brabant to Nijmegen. His recommendation of another using the IJssel and the Dutch portion of the Lower Rhine to defend the east formed the basis of a NATO defence line constructed in the 1950s, codenamed Plans 'C' for Coehoorn and 'D' for Deventer.[12]

Namur; the Sieges of 1692 and 1695

There was interest in his ideas but they remained untested; this changed with the outbreak of the 1688-1697 Nine Years War which placed great emphasis on manoeuvre and siege warfare.[13] Van Coehoorn was present at the capture of Kaiserswerth and Bonn in 1690; his exact role is unclear but Frederick of Prussia was impressed enough to offer him a position as Major-General in his army.[2] He refused and in 1691 William appointed him commander of Namur where he was finally able to implement his ideas on defensive strategy.

Namur was divided into the 'City' on the flat northern bank of the River Sambre and the Citadel on high ground to the south controlling access to the Sambre and Meuse rivers. Van Coehoorn strengthened the 'inner' Citadel with new outworks at Fort William and La Casotte but did not have time to do the same for the 'outer' City area. His garrison of 5,000 [lower-alpha 5] was also too small for the active defence he had planned, many being poorly-trained Spanish troops with little interest in fighting for the Dutch.[14]

In the first Siege of Namur in May 1692, the City fell in less than five days, with the Citadel and its 500 Dutch defenders holding out until 30 June. This was partly due to the terms negotiated by Van Coehoorn when surrendering the City. He agreed not to fire on the City from the Citadel in return for the French not attacking from that direction, making it almost impregnable.[14]

Regardless, the defence was a significant achievement and William III promoted Van Coehoorn to Major-General and commander of the vital city of Liège. He also supervised the construction of new defences at Huy which the Dutch lost in July 1693 but recaptured in September 1694.

The focus of the 1695 Allied campaign was the second Siege of Namur. The fortifications had been strengthened by Vauban, while Marshall Boufflers had a garrison of 13,000 that was large enough to conduct an active defence. Van Coehoorn was put in charge of siege operations; the outer City was quickly captured but by mid-August the Citadel remained largely intact. William was growing impatient; siege warfare was a balance between acceptable casualties and time, particularly in an age when far more soldiers died of sickness than in combat. Van Coehoorn established a battery of 200 guns and on 21 August began a continuous 24 hour bombardment of the Citadel's lower defences. Assaults on the resulting breaches were extremely bloody, including 3,000 casualties in three hours on 30 August but the defenders surrendered on 4 September.[15]

The two sieges of Namur were the key events of the Nine Years War in Flanders and made Van Coehoorn's reputation. Nieuwe Vestingbouw was translated into English, French and German among others and reprinted on a regular basis while his ideas were widely used elsewhere, including Mannheim, Belgrade and Temesvar. Ironically, Boufflers' defence of Namur was the best example of Van Coehoorn's defensive principles. He ...demonstrated one could effectively win a campaign by losing a fortress but exhausting the besieging force...(Boufflers) conducted a classic active defence and contested every advance as best he could.[16]

Rather than the accepted practice of targeting multiple areas, both Vauban and Van Coehoorn focused their siege artillery on specific parts of the fortifications. Overwhelming defences with massive firepower was known as the 'Van Coehoorn method,' while Vauban preferred a more gradual approach.[17] He argued this was more efficient in the use of artillery and less costly in terms of casualties but it relied on the then accepted convention that defenders surrendered when 'a practicable breach' had been made.[lower-alpha 6][18] Both methods had their supporters.

Later career

.jpg)

In recognition of his part in the capture of Namur, Van Coehoorn was promoted Lieutenant General and appointed Ingenieur Generaal der Fortificatiën and General of Artillery. His brother Gideon replaced him as Colonel of the Nassau Friesland Regiment, while Van Coehoorn himself transferred to a Holland regiment; this increased his influence, since he now reported to William, rather than the Frisian Stadholder Hendrik Casimir.

The 1697 Treaty of Ryswick ending the Nine Year War allowed the Dutch to garrison Nieuwpoort, Charleroi, Luxembourg, Mons and Namur in the Spanish Netherlands although these all fell rapidly to the French in 1701.[4] In his new role, Van Coehoorn was responsible for the Dutch Republic's fortifications.

One of his strengths was adapting his methods to fit individual sites and minimising costs, essential skills as the Dutch had insufficient funds for all the repairs and additions needed.[19] Nijmegen and Bergen op Zoom were prioritised for upgrades although both were incomplete in 1701 when the War of the Spanish Succession broke out.[20] Van Coehoorn was appointed Governor of Sluis and military commander in Zeeuws Vlaanderen or Zeelandic Flanders.

John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, commander of the Anglo-Dutch forces advocated a more aggressive strategy, arguing one battle was more beneficial than taking 12 fortresses and Van Coehoorn himself supported this approach.[21] However, the Dutch had survived a century of almost constant warfare by keeping their army together; losing a battle might lose them the war and they considered Marlborough's approach unnecessarily risky.[22]

Instead, the Allies spent 1702 and 1703 taking towns such as Venlo and Roermond in the modern Dutch province of Limburg,[lower-alpha 7] as well as Liège, Bonn and Huy. Failure to take Antwerp in May 1703 ended hopes of a quick victory while a Dutch army under Slangenburg was surrounded by a French force several times their size at Ekeren on 30 June and only just escaped. Recriminations were considerable, with Slangenburg blaming his commander Obdam but also Marlborough and Van Coehoorn for failing to support him.

Van Coehoorn was a difficult character with few friends while William's death in March 1702 deprived him of his most powerful sponsor and much of his influence.[23] The campaigns of 1702 and 1703 showed his limitations as a field officer and led to criticism from both Marlborough and Dutch colleagues.[lower-alpha 8][24] In early 1704, he spoke with the Envoy of Savoy about possible opportunities in their army but died on 17 March in The Hague attending a conference with Marlborough.[25] He is buried at Wijckel where the Frisian States sponsored the erection of a monument over his grave.

Other

In May 1701, Van Coehoorn demonstrated a light-weight mortar to William, later known as the Coehorn (sic). Designed to provide cover for infantry assaults, it was first used at Kaiserworth in 1702 and variations remained in service during the US Civil War in 1861.[26]

The Menno van Coehoorn Foundation was established in 1932 to preserve the cultural heritage of historical fortifications in the Netherlands and their associated wildlife.

His son Gosewijn Theodor van Coehoorn (1678-1736) wrote a biography of his father, The Life Of Menno Baron Van Coehoorn which is still in print. In his five book "Saga"The Witcher Polish fantasy writer Andrzej Sapkowski named one of the Nilfgaard marshals Van Coehoorn.

Notes

- ↑ At that period, Captains 'owned' their companies and were responsible for payment of wages etc

- ↑ Nijmegen surrendered after five days, Fort Crèvecœur in two.

- ↑ Variously delivered from loopholed redoubts in the re-entrant places-of-arms, from earthen faussebrayes, and long, concave double-bastioned flanks. These works were screened from view by their low profiles, and, in the case of the flanks, by narrow, tower-like orillons of solid masonry;"[8]

- ↑ Van Coehoorn gives three "methods" to illustrate his principles; in the first, the weight of the defense rests on the complex formed by a combined bastion and faussebraye. In the second, the emphasis is transferred to a continuous envelope; in the third bastions and envelope are replaced by enormous ravelins and lunettes.Cf. plates 39-41 in Duffy pp. 68-70 In his later career Van Coehoorn did not slavishly follow these principles, but paid much attention to local circumstances.[11]

- ↑ Other sources suggest 8,000 - 9,000.

- ↑ Defenders who fought on past that point were often massacred and the town pillaged.

- ↑ Distinct from the modern Belgian/Flemish province of the same name

- ↑ 'Mr Van Coehoorn enrages us with his delays and all the measures that must be made because he never lets us know beforehand what he needs.' Marlborough to Heinsius, Venlo, 24 September 1702.

References

- 1 2 3 Eysten, p. 620

- 1 2 Duffy, p. 63

- ↑ Eysten, p. 622

- 1 2 Duffy, p. 35

- ↑ Van Nimwegen, Olaf (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588-1688. Boydell Press. p. 105. ISBN 1843835754.

- ↑ Afflerbach & Strachan, p. 159

- ↑ Nolan, Cathal (2008). "Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare". Google Books U.K. Greenwood. p. 84. ISBN 0313330468. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ↑ Duffy, p. 67

- ↑ Duffy, p. 68

- ↑ Duffy, pp. 68-69

- ↑ Duffy, p. 71

- ↑ Hoof van, JCPM. "Menno van Coehoorn, een historische schets". Menno van Coehoorn Foundation. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ↑ Childs (1991), p. 2

- 1 2 Martin de la Colonie, p. 16

- ↑ Lenihan, Padraig (2011). "Namur Citadel, 1695: A Case Study in Allied Siege Tactics". War in History. 18 (3): 25–26. doi:10.1177/0968344511401296.

- ↑ Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. pp. 248–249. ISBN 0582056292.

- ↑ Ostwald, pp. 285-286

- ↑ Afflerbach & Strachan, pp.159-160

- ↑ Duffy, pp. 65-70

- ↑ Duffy, p. 34

- ↑ Van Hoof, Jaep (2004). Menno van Coehoorn 1641 - 1704, Vestingbouwer ~ belegeraar ~ infanterist. Instituut voor Militaire Geschiedenis. p. 83.

- ↑ Bromley, A.S (ed) (1970). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 6, The Rise of Great Britain and Russia, 1688-1715 (1979 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 416. ISBN 0521293960.

- ↑ Ostwald, p. 114

- ↑ Ostwald, p. 237

- ↑ Duffy, p. 64

- ↑ Duffy, p. 65

Sources

- Afflerbach, Holger (ed), Strachan, Hew (ed) (2012). How Fighting Ends: A History of Surrender. OUP. ISBN 0199693625. ;

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719089964. ;

- Childs, John (1990). The British Army of William III, 1689-1702. Manchester University Press. ;

- Coehoorn, M. van (1685). "Nieuwe vestingbouw, op een natte of lage horisont; etc". Google Books (in Dutch). Hendrik Rintjes. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- Coehoorn, Gozewijn Theodoor van, Sypesteyn, Willem Jan van (1860). Het Leven Van Menno Baron Van Coehoorn (in Dutch). Kessinger Publishing Co. ISBN 1104059185.

- Duffy, Christopher (1985). "The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great 1660-1789". Google Books. Routledge. ISBN 1138924644. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- Eysten (1911). "Coehoorn (Menno baron van), in: P.J. Blok, P.C. Molhuysen (eds)., Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek. Deel 1". Digitale Bibliotheek der Nederlandse Letteren (in Dutch). pp. 620–622. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- Hoof van, Joep (2004). "Menno van Coehoorn 1641 - 1704, Vestingbouwer ~ belegeraar ~ infanterist" (in Dutch). Instituut voor Militaire Geschiedenis. Missing or empty

|url=(help) ; - Lenihan, Padraig (2011). "Namur Citadel, 1695: A Case Study in Allied Siege Tactics". Sage. doi:10.1177/0968344511401296. Missing or empty

|url=(help) ; - Martin de la Colonie, Horsley, Walter (1904). The Chronicles of an Old Campaigner M. de la Colonie, 1692-1717 (2015 ed.). Scholars Choice. ISBN 1296409791. ;

- Ostwald, Jamel (2006). Vauban Under Siege: Engineering Efficiency and Martial Vigor in the War of the Spanish Succession. Brill. ISBN 9004154892. ;

- Roo van Alderwerelt, J.K.H. de (1862). "De Vestingoorlog en de Vestingbouw in hunne ontwikkeling beschouwd". Google Books (in Dutch). M.J. Visser. Retrieved June 8, 2018. ;

- Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV. iUniverse. ;

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Menno van Coehoorn. |