Maulbronn Monastery

| Maulbronn Monastery | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German: Kloster Maulbronn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Maulbronn Abbey, circa 2017

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official name | Maulbronn Monastery Complex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iv) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reference | 546rev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inscription | 1993 (17th Session) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 49°0′4″N 8°48′46″E / 49.00111°N 8.81278°E

| Imperial Monastery of Maulbronn Reichskloster Maulbronn | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1147–1806 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Imperial Abbey | ||||||||

| Capital | Maulbronn | ||||||||

| Government | Theocracy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Founded as Imperial abbey | 1147 | ||||||||

• Placed under Imperial protection | 1156 | ||||||||

• Seized by Württemberg | 1504 | ||||||||

• Monastery alternates between Protestantism and Cistercians | 1534–1651 | ||||||||

• Peace of Westphalia settles monastery to Protestantism | 1648 | ||||||||

| 1806 | |||||||||

• Seminary merged with that of Bebenhausen | 1818 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||

Maulbronn Monastery (German: Kloster Maulbronn) is a former Roman Catholic Cistercian Abbey and Protestant seminary at Maulbronn, Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg. The 850 year old, mostly Romanesque monastery complex, one of the best preserved examples of its kind in Europe, is one of the very first buildings in Germany to use the Gothic style. In 1993, the abbey was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1]

The complex, surrounded by turreted walls and a tower gate, today houses the Maulbronn town hall and other administrative offices, a police station, and several restaurants. The monastery itself contains an Evangelical seminary in the Württemberger tradition and a boarding school.

Founding

As early as 1138, the Cistercians had established a religious community in Eckenweihar, near modern day Mühlacker, a plot of land a free knight named Walter von Lomersheim had donated to the order.[2] Twelve monks and an unspecified number of lay brothers headed by Abbot Diether set out from Neubourg Abbey in Alsace for Eckenweihar on the request of von Lomersheim,[3] arriving on 23 March 1138.[4] The site was found to be geographically unsuitable for a monastery, so Günther von Henneberg, Bishop of Speyer, deeded to the Eckenweihar community the fiefdom of Mulinbrunn from Hirsau Abbey and moved them there in 1147.[5][6][lower-alpha 1] Local legends tell that the Cistercians decided to use a mule to locate water, and built the monastery at its present location when it either struck water from a stone or drank from a stream. Etymology of the name "Mulenbrunnen," the root of Maulbronn ("Maul" is German for "Mule"), reveals that the monastery was likely founded at the site of a spring and a watermill.[7]

Development

From 1156, the monastery was a Vogtei of the Holy Roman Empire, and was confirmed in 1332. However, the abbey continued chose to be under the protection of the Bishop of Speyer, who awarded the title as a sub-Vogt to his minister Heinrich von Enzberg, who would from 1236 appear in documentation as the protector of the abbey. Over the following decades, Maulbronn monastery would struggle, sometimes violently, with the von Enzbergs who tried to use their protection of the monastery to expand their own power base. From 1325 onward the Rhenish Palatine Counts were entrusted with the Vogt title.

In 1504, Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg laid siege to Maulbronn and captured it after seven days during the War of the Succession of Landshut.

In 1525, during the German Peasants' War, the monastery was looted by rebel forces. Their leader, Jäcklein Rohrbach, stayed at Maulbronn for a time and complained to Hans Wunderer of the disorganization of the peasant force who were unable to decide whether to demolish or ransom the abbey. Due to Rohrbach's intercession, Maulbronn Abbey still exists today.

Because the Duchy of Württemberg became Protestant, the monks of the abbey were no longer tolerated by the political authority of the state. The monastery was at first intended to be a collection monastery (German: Sammelkloster) for retired monks from all the remaining monasteries in Württemberg. In 1537, the abbot and the convent moved to Pairis Abbey in Alsace, the abbot died 1547 in Einsiedeln. After the defeat of the Schmalkaldic League, Ulrich had to return the monastery to the Cistercians in 1546-47.

The Peace of Augsburg gave the Duke the right to decide on the faith of his subjects. In 1556 he issued the Württemberger Klosterordnung, a decree that would form the basis for a regulated education system in all the remaining monasteries for men in Württemberg. The conversion of the monastery into a school remained legally disputed for a long time, the Emperor trying twice to reverse this development. During the Interims from 1548–1555 and 1630–1649 due to the Imperial restitution edicts, monks could return to the monastery due to the temporary political situation of the time.

The possessions of the Abbey grew first and foremost through donations and endowments. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the abbey's possessions were realigned via purchase so as to make its boundaries more compact. At the end of this development, the monastery's possessions included 20 villages, called Klosterflecken. Besides the income provided by the abbey's immediate surroundings, there were also cottage industries in Illingen, Knittlingen, and Unteröwisheim and 6000 acres of forest, spread out over 25 villages, that were administered by the abbey. Land privileges were loaned out for additional income in addition to the tithe, giving the abbey enormous income as a result, illustrated by the size of the abbey's granary. To manage this income, the abbey had seven Pfleghöfe, located in Illingen, Kirchheim am Neckar, Knittlingen, Ötisheim, Speyer, Unteröwisheim and Wiernsheim.

After the Reformation began in the year 1517, Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg built his hunting lodge and stables here. The monastery was pillaged repeatedly: first by the knights under Franz von Sickingen in 1519, then again during the German Peasants' War six years later. In 1534, Duke Ulrich secularized the monastery, but the Cistercians regained control — and Imperial recognition — under Charles V's Augsburg Interim.

In 1556, Christoph, Duke of Württemberg, established a Protestant seminary,[8] with Valentin Vannius becoming its first abbot two years later although the Reformation banned religious orders and abbots; Johannes Kepler studied there 1586–89.

In 1630, the abbey was returned to the Cistercians by force of arms, with Christoph Schaller von Sennheim becoming abbot. This restoration was short-lived, however, as Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden forced the monks to leave again two years later, with a Protestant abbot returning in 1633; the seminary reopened the following year, however the Cistercians under Schaller also returned in 1634. Under the Peace of Westphalia, in 1648, the confession of the monastery was settled in favor of Protestantism; with abbot Buchinger withdrawing in process. A Protestant abbacy was re-established in 1651, with the seminary reopening five years later. In 1692, the seminarians were removed to safety when Ezéchiel du Mas, Comte de Mélac, torched the school, which remained closed for a decade.

The monastery was secularized by King Frederick I of Württemberg, in the course of the German Mediatisation in 1807, forever removing its political quasi-independence; the seminary merged with that of Bebenhausen the following year, now known as the Evangelical Seminaries of Maulbronn and Blaubeuren.

The monastery, which features prominently in Hermann Hesse's novel Beneath the Wheel, was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1993. The justification for the inscription was as follows: "The Maulbronn complex is the most complete survival of a Cistercian monastic establishment in Europe, in particular because of the survival of its extensive water-management system of reservoirs and channels". Hesse himself attended the seminary before fleeing in 1891 after a suicide attempt, and a failed attempt to save Hesse from his personal religious crisis by a well-known theologian and faith healer.

To represent Baden-Württemberg, an image of the Abbey appears on the obverse of the German 2013 €2 commemorative coin.[9]

Architecture

Founded and built from 1147,[8] Maulbronn Monastery was constructed in a Romanesque style,[10] then native to Swabia. Examples of the "Hirsau style" are the church's uniform pillars and the rectangular frames around the Romanesque arches. Near the end of the 12th century the architecture of the Cistercians became influenced by Gothic architecture, which required less stone than the Romanesque style, and the order began disseminating it from northeastern France. At Maulbronn the "Master of the Paradise," an anonymous architect trained in Paris, erected the first example of Gothic architecture in Germany: the narthex of the church,[11] dubbed the "Paradise." The Late Gothic came to Maulbronn from the late 13th century to the mid-14th century, and again in the German Romantic era of the late 19th century.[10]

Although little of the 12th century work, such as the portal and its original doors, have been preserved,[10] the monastery as a whole survives due mostly to the Dukes of Württemberg, who obtained ownership of it in the 16th century.[12] Today, Maulbronn is considered the best preserved medieval monastery complex north of the Alps.[1]

As was customary with Cistercian monasteries,[13] Maulbronn stands on top of a sophisticated water management system.[14] By draining the wetlands around the monastery and digging a series of canals,[13] the monks created some 20 ponds and lakes and diverted the Salzach, a local stream, under the monastery to form its sewerage.[15] The water levels in these lakes could be controlled, allowing Maulbronn's monks to power their mill,[16] but also to raise fish for consumption or commerce.[17][lower-alpha 2] Much of the system remains in use,[15] and it is part of Maulbronn's UNESCO inscription.[1]

The monastery was protected by stone wall, a drawbridge gate, and five towers.[18]

Abbey

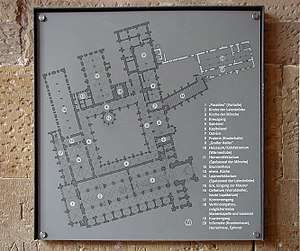

Although the Cistercian Order banned heated rooms,[12] Maulbronn has a calefactory (Room 10 on the plan) that was heated by lighting a fire in a vaulted chamber underneath the calefactory's floor. Smoke was funneled outside and the heat rose into the calefactory through 20 holes in its floor.[20]

The frescoes in the church were painted by a lay brother] known only as Ulrich. They depict the Adoration of the Magi, the entrance of Maulbronn's founder Walter von Lomersheim into the monastery as a lay brother and the coats of arms of nobles who donated funds to the monastery's construction.[19]

Duke's lodge

The Dukes of Württemberg controlled Maulbronn from the early 16th century, and Duke Louis III established a lustschloss here.[21]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maulbronn Monastery complex. |

- Gothic architecture

- Romanesque architecture

- List of Cistercian monasteries in Germany

- Salem Abbey

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ While the move from Eckenweihar to Maulbronn occurred in 1147, the deed confirming the ceding of Maulbronn from Hirsau Abbey was crafted and confirmed a decade later.[5]

- ↑ Cistercians were forbidden from eating meat, but consuming fish was allowable as they were classified as "river vegetables." The monks of Maulbronn raised their fish, most notably the mirror carp, in different bodies of water depending on their species, size, and age, then sold them to surrounding communities.[17]

Citations

- 1 2 3 UNESCO: Maulbronn Monastery Complex.

- ↑ Maulbronn Monastery: Meilensteine.

- ↑ Klöster in Baden-Württemberg: Eckenweiher.

- ↑ Klunzinger 1854, p. 12.

- 1 2 Landesarchiv Württemberg: WUB Band II, #355.

- ↑ Klöster in Baden-Württemberg: Maulbronn.

- ↑ Maulbronn Monastery: Gründungslengende.

- 1 2 Maulbronn Monastery: Gebäude.

- ↑ European Union Journal, 28 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 Maulbronn Monastery: Stilgeschichte.

- ↑ Burton & Kerr 2011, pp. 77, 78-79.

- 1 2 Jeep 2001, p. 508.

- 1 2 Burton & Kerr 2011, p. 69.

- ↑ Baden-Württemberg: Kloster Maulbronn.

- 1 2 Maulbronn Monastery: Wasserwirtschaft.

- ↑ Maulbronn Monastery: Umgebung des Klosters.

- 1 2 Maulbronn Monastery: Fischzucht.

- ↑ Burton & Kerr 2011, p. 75.

- 1 2 Burton & Kerr 2011, p. 81.

- ↑ Kinder 2002, p. 279.

- ↑ Maulbronn Monastery: Kloster.

References

- Burton, Janet B.; Kerr, Julie (2011). The Cistercians in the Middle Ages. Monastic orders. Volume 4 (Illustrated ed.). Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843836674.

- Jeep, John M. (2001). Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780824076443.

- Kinder, Terryl M. (2002). Cistercian Europe: Architecture of Contemplation. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802838872.

- Klunzinger, Karl (1854). Urkundliche Geschichte der vormaligen Cisterzienser-Abtei Maulbronn (in German). C.A. Sonnewald.

- Landesarchiv Württemberg

- "Württemberg Urkundenbuch Band II., Nr. 355, Seite 104". Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Klöster in Baden-Württemberg

- Rückert, Peter. "Zisterzienserkloster Eckenweiher - Geschichte". Klöster in Baden-Württemberg. Landesarchiv Württemberg. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Rückert, Peter. "Zisterzienserabtei Maulbronn - Geschichte". Klöster in Baden-Württemberg. Landesarchiv Württemberg. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

Online references

- "Official Journal of the European Union" (PDF). European Union. 28 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- UNESCO

- "Maulbronn Monastery Complex". UNESCO World Heritage. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Government of Baden-Württemberg (in German)

- "Kloster Maulbronn". Baden-Württemberg Landesdenkmalpflege. State of Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Baden-Württemberg State Agency of Palaces and Gardens (in German)

- "Das Kloster". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Gebäude". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Gärten". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Meilensteine". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- "Stilgeschichte". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- "Die Umgebung des Klosters". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Die Fischzucht". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Die Wasserwirtschaft". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Die Gründungslengende". kloster-maulbronn.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 16 July 2018.