Marine life of New York–New Jersey Harbor Estuary

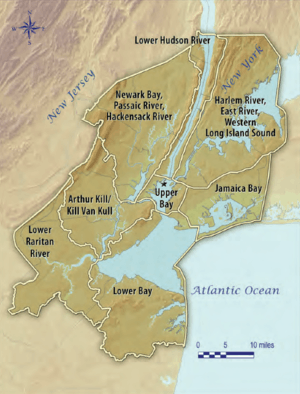

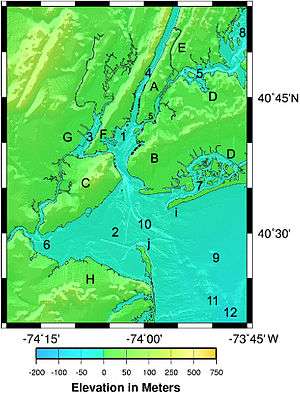

The marine life of New York–New Jersey Harbor Estuary refers to the variety of flora and fauna in and around Port of New York and New Jersey. For bodies of water within the estuary see Geography of New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary. Much of the harbor originally consisted of tidal marshes that have been dramatically transformed by the development of port facilities.[1] The estuary itself supports a great variety of thriving estuarine aquatic species; contrary to popular stereotypes, New York Harbor and its adjacent, interdependent waters are very much alive, and recovering from pollution. Tidal flow occurs as far north as Troy, over 150 miles away. The salt front (dilute salt water) can reach Poughkeepsie in drought conditions and is present in the lower reaches of the Raritan River for most of the year.[2]

Animal species

Arthropods

- American lobster (Homarus americanus) - Massachusetts Bay is not the only home of the lobster on the East Coast. Usually found south of the Verrazano Bridge, near the Southwestern end of Long Island and just off Sandy Hook. Often attracted to artificial reefs found near Lower New York Bay, where they can reach very large sizes. Depredation by man within the New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary is extremely rare.

- Atlantic rock crab (Cancer irroratus) - A common crab found on the continental shelf within ten miles of shoreline. Found in all parts of the estuary. There is some concern over it competing with the invasive European green crab for habitat, but it is believed that the presence of Callinectes genera in the bight may offer some refuge as it has been shown that the swimmer crabs of this genus like to prey upon the smaller green crab.

- Blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) - Also known as the blue claw crab. The crabs are typically found in the mouth of the Hudson River and occasionally wander into the brackish waters of small rivers and coves that pepper the western side of Long Island; up the Hudson they are found occasionally in the part of the river that runs through the lower Hudson Valley in the summertime. Up until the 1960s they could be eaten, but the State of New York currently recommends against attempting to do so on a regular basis, due to bioaccumulation of PCBs and cadmium that were discovered in the crabs in the 1970s. On the upside, a lack of hunting by man has caused this crab's numbers to grow heartily while others (notably the Chesapeake Bay) have decreased.[3]

- Ghost crab (Ocypode quadrata) - Common sight after twilight scurrying along the beaches of western Long Island and the planktonic larvae is found all throughout the estuary.

- Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) - A common visitor to Breezy Point, Rockaways, and Coney Island. Numbers in peril but not yet a candidate as an endangered species.

- Lady crab (Ovalipes ocellatus)

- Portly spider crab (Libinia emarginata)

- Ivory barnacle (Amphibalanus eburneus)

- Northern rock barnacle (Semibalanus balanoides)

- Asian shore crab (Hemigraspus sanguineus)

- Common Spider Crab (Libinia emarginata)

- Green Crab (Carcinus maenus) This species is an invasive species originally from Europe that has been present in all waters of the State of New York for many decades. It is a swimmer crab that is present in most parts of the harbor and is easily distinguished from the blue crab by being much smaller and a dull green color.

- Black fingered mud crab (Panopeus herbstii)

- Gammarid Amphipod (Family Gammaridae)

- Corophid amphipod (Family Corophiidae)

- Skeleton Shrimp ('Family Caprellida)

- Shore Shrimp, Grass Shrimp (Palaemonetes spp.)

- Sea Roach (Family idoteidae)

- White fingered mud crab (Rhithropanopeus harrisii)

Chordates

Although not aquatic animals, these birds are supported by the food and habitat the harbor provides, particularly Jamaica Bay and the Pelham Islands. Many of these birds will fly within sight of the Manhattan skyline and the estuary is a very important point for the East Coast because of its location: it is dead center in the Atlantic Flyway and many raptors and waterfowl use this spot as a rest area along their journey from New England and Canada in fall before heading further south to the Southern States and the Caribbean, reversing the journey in late March and early April.

- American herring gull (Larus smithsonianus) A common sight that is present almost year round. Some will nest on the many tall buildings afforded in all five boroughs, none of which is more than a few miles from the water.

- Black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax)

- Great blue heron (Ardea herodia)

- Snowy egret (Egretta thula) A common visitor to streams and salt marshes in the summer. Will on rare occasions be found foraging and relaxing in parks and rivers in the estuary system like the Bronx River.

- Yellow-crowned night heron (Nycticorax violaceus) - Nests on some of the uninhabited islands in the harbor and feasts upon the fish in the ocean and frogs in the streams

- American oystercatcher (Haematopus pallatius)

- American wigeon (Anas americana)

- Bald eagle (Halieeatus leucocephalus) - Has been seen up the Hudson River every winter consistently for well over a decade, feeding on a wide variety of both freshwater and saltwater fish. Has also been seen using the New Jersey Palisades and piers near the Harlem River as a perch from which to swoop down and grab its quarry in the estuary. Will occasionally make itself known in the Lower Harbor seeking schools of mackerel.

- Black skimmer (Rynchops niger)

- Brant (Branta bernicla hrota)

- Canada goose (Branta canadensis)

- Mallard (Anas platyryncha) The most common dabbling duck in the region. Will from time to time swim near the docks.

- Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) - A very common sight in the skies over western Long Island, especially during the nesting months.

Fish

- Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus)

- American butterfish (Peprilus triacanthus)

- American eel (Anguilla rostrata)

- American shad (Alosa sapidissima)

- Atlantic croaker (Micropogonias undulatus)

- Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus)

- Atlantic menhaden (Brevoortia tyrannus): A success story. In the 1940s and 1950s, the waters of the Estuary were very badly polluted and had been polluted since at least the mid 19th century. By the time of the Clean Water Act, it was ecologically near dead. As of 2018 the water is clean enough to support this fish in large numbers, which have in turn triggered the return of whales to the harbor.

- Atlantic needlefish (Strongylura marina)

- Atlantic silverside (Menidia menidia)

- Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) - Found in the depths of Upper New York Bay, in the main channel of the Hudson River. Increasingly rare on the East Coast, but New York Bay and the Hudson are known strongholds where locals do not hunt this fish.

- Black drum (Pogonias cromis)

- Bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix)

- Gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum)

- Lined seahorse (Hippocampus erectus)

- Mummichog (Fundulus heteroclitus)

- Northern pipefish (Syngnathus fuscus)

- Oyster toadfish (Opsanus tau)

- Sand lance (Ammodytes americanus)

- Scup (Stenatomus chrysops)

- Shortnose Sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum)

- Skillet fish (Gobiesox strumosus)

- Striped bass (Morone saxatilis) - One of the most prevalent species in the harbor, and the most extensively fished one. The Hudson River Estuary system has been a nursery for stripers going back before European settlement and overall it is one of the most important breeding grounds for this species in the Northeast.

- Summer flounder (Paralicthys dentatus)

- Tautog (Tautoga onitis) Locally known also as the blackfish. Attracted to artificial reefs and natural shoals in the estuary.

- Tomcod (Microgadus tomcod)

- Weakfish (Cynoscion regalis)

- White perch (Morone americana)

- Winter flounder (Pleuronectes americanus)

Sharks

Despite popular belief, sharks are perfectly capable of living in the waters of the estuary from the very small species to the giants, with 25 of them being recorded as indigenous to the waters of New York State.[4] The overwhelming majority have no interest in hunting humans as there is already plenty of good prey available for them to hunt. The exact migration pattern is not completely known, but the general belief is that the larger pelagic sharks migrate north in the spring and return again to Florida and Georgia by the end of November.

- Great white shark(Carcharodon carcharias) One of the largest living species of shark. As of 2018, recent research indicates the return of this most feared shark, including the spotting of a large female very close to Brooklyn. Has been seen near Sandy Hook and Coney Island; there is a nursery off Montauk where females are suspected to give birth and to a shark the waters surrounding New York City are a short trip away. This species has been returning to old haunts from Maryland in the South to Nova Scotia in the north, following their favorite food: gray seals. Juveniles are most commonly found in Upper New York Bay.

- Nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) Will occasionally visit artificial reefs.

- Bull shark Historically responsible for an incident in Matawan, NJ that inspired the film Jaws. Still lives in the waters seasonally, migrating south to Florida as the weather cools.

- Shortfin mako shark Isurus oxyrinchus

- Sand tiger shark Carcharias taurus

- Blue shark Prionace glauca

Mammals

- Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

- Grey seal (Halichoerus gryphus)

- Harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) - Historically both pinniped species were abundant natives in the harbor until hunting and other human activity extirpated them from the area by at least the late 19th century: there is a section of the harbor that was historically known as "Robbins Reef. " Robyn is the Dutch word for seal, proving their existence long before the American Revolution.[5] In recent years, however, these two species, along with the some more typically northerly seal species like the harp seal have been found in the harbor in pursuit of some of the species mentioned above; others are yearlings who are continuing the trend on the U.S. East Coast of seals reclaiming former habitat, heading southward from mother populations in New England and Canada and from more easterly parts of Long Island. Colonies of harbor seals can be found happily basking in the sun off Staten Island and Jamaica Bay from December through April, and as of 2011 they have been spotted playing just off Coney Island.

- Harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) - Has been seen in Upper New York Bay.

- North American river otter (Lutra canadensis) - Native to the Hudson River and occasionally is seen at the mouth of the river. Restoration efforts by the state of New York are underway and appear to be successful.

Whales

- Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) The largest of all whale species, and one of the rarest. Can be found just off Sandy Hook.

- Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

- Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Among whales, one of the most common visitors to the Harbor as of 2018. Usually humpbacks appear in the harbor around April and will not leave until late October: New York City and its surrounding waters are dead in the middle of their migration route, a huge territory that extends from Newfoundland in Canada to the strait between Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. The estuary is an excellent pit stop for mother whales wanting to teach their calves how to catch the fish that have returned in numbers not seen in over a century. In 2017 one humpback whale made international news when it breached in front of a camera less than a few miles from Battery Park and raised awareness that whales have "come home" at last to New York.[6]

- Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata)

- North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis)

From 2007-2009, an expert from Cornell University did an experiment listening in on the acoustics of the Harbor Estuary, where, to the astonishment of many, he discovered at least six species of whale vocalizing less than 20 miles from where the Statue of Liberty stands, just past the Verrazano Bridge where the water gets deeper.[7][8] Historical records show that whales were plentiful in the area going well back into colonial history: in 1697, the charter for Trinity Church received its official royal charter, which gave it not only a large chunk of land in Lower Manhattan, but also the profit from any whales or shipwrecks along the banks of the Hudson.[9] The return of these whales is evidence of the environment's improvement over the past thirty years: whales have been absent from New York's waters west of the Hamptons for over a hundred years as the water became incredibly polluted and in 1989 the population was zero. In 2009, however, a young humpback whale attempted to penetrate the gateway to the upper harbor when it passed under the Verrazano Bridge, causing the men and women ashore watching the whole debacle from Fort Hamilton a great deal of alarm, concerned for its health and the safety of the Coast Guard officers trying to herd the frightened, massive creature back out to sea (the whale returned unharmed.)[10] In late 2017, for the first time, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in partnership with the New York Aquarium began to count the whales in a census as the population has expanded mightily.[11]

Tunicates

- Golden star tunicate (Botryllus schlosseri)

- Chain tunicate (Botrylloides violaceus)

- Orange sheath tunicate (Botrylloides diegensis)

- Sea grapes (Molgula manhattensis)

- Sea vase (Ciona intestinalis)

Cnidarians

- Moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) A common sight that washes up on the shores of Rockaways, Queens every summer.

- White cross hydromedusa (Staurophora mertensi)

- Tubular hydroid (Ectopleura crocea)

Echinoderms

- Atlantic starfish (Asterias forbesi)

- Northern sea star (Asterias vulgaris)

Mollusks

Bivalves

- Atlantic bay scallop (Aequipectin irradians)

- Atlantic jackknife clam (Ensis directus) Also known as a bamboo clam or razor clam.

- Atlantic ridged marsh mussel (Geukensia demissa)

- Atlantic strawberry cockle (Americardia media)[12]

- Atlantic surf clam (Spisula solidissima) A species that is much prized as a food source. Very common near Sandy Hook.

- Blue mussel (Mytulis edulis)

- Coquina (Donax fossor) A very small species that is found where the tide meets the sand.

- Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) - Once widely found through much of the harbor and a staple of the local diet from the time of the Algonquians up through the 19th century. Oystering grounds were prevalent in the Upper Bay, as well as along the south shore of Staten Island and Jamaica Bay. The oyster still exists in the harbor but is not yet considered edible; there are plans to further clean up the areas so that the beds can be restored.

- Quahog (Venus mercenaria)

- Steamer clam (Mya arenaria)

Cephalopods

- Longfin inshore squid (Loligo pealei) - Found in Lower New York Harbor and Sheepshead Bay. Often for sale in local farmers' markets.

- Common octopus

Gastropods

- Channeled whelk (Busycon canaliculatum)

- Common periwinkle (Littorina littorea) - Almost certainly introduced in colonial times by the British as food and possibly in bilgewater from ships. Common sight clinging to rocks or wherever their favorite algae can grow.

- Eastern mudsnail (Ilanassa obsoleta)

- Oyster drill (Urosalpinx cinerea)

Annelida

Bryozoans

- Lacy Bryozoan (Membranipora membranacea)

- Orange Bryozoan (Watersipora subtorquata)

- Brown Bushy Bryozoan ('Bulgula neritina)

Algae

- Sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca)

- Hollow Green Weed (Enteromorphia spp.)

- Sour Weeds (Desmarestia spp.)

References

- ↑ NY/NJ Estuary

- ↑ Hudson Estuary Basics Dept. of Environmental Conservation, NY State.

- ↑ https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:BwGdC-rWyD4J:www.njmsc.org/education/Lesson_Plans/Key/Blue_Crab.pdf+blue+crab+hudson+river&hl=en&gl=us&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEESjHUP7Qb-721t1sNd9fx852frAADj2Kw0GDb7rRpYtuZotDLWOf2S49SV4zTZ3w_robcahjWv3pXL_yl42bRys5dfuVhx-Wf2GDE4TUqdYwHK7XSIcE_qgJgIEseF43i0rlm3O9&sig=AHIEtbTT7RSYoitcrHVyTWncnLxw4vk_6g

- ↑ "Sharks - Blue York". blueyork.org. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ↑ Goodier, John (December 2004). "The Lighthouse Encyclopedia: The Definitive Reference2004445Edited by Ray Jones. The Lighthouse Encyclopedia: The Definitive Reference. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press 2004. 274 pp., £22.50/$27.95". Reference Reviews. 18 (8): 39–39. doi:10.1108/09504120410565891. ISBN 0 7627 2735 7. ISSN 0950-4125.

- ↑ "The whales off the coast of New York". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ↑ http://www.biology-online.org/kb/article.php?p=blue-whale-discovered-singing-york

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ http://blog.insidetheapple.net/2008/09/whales-in-new-york-past-and-present.html

- ↑ http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/04/09/humpback-whale-spotted-in-new-york-harbor/

- ↑ News, A. B. C. (2017-08-29). "Why whales are returning to New York City's once polluted waters 'by the ton'". ABC News. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ↑ "GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY OF THE NEW YORK BIGHT". www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu. Retrieved 2018-06-23.

- NY/NJ Estuary

- "Fishing for Answers in an Urban Estuary" - Teaching Guide About Newark Bay for Elementary Schools (NJDEP)

- New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program - US EPA

- US EPA: Newark Bay Study 2004

- US Army Corps of Engineers: Newark Bay

- Cornell University