Magnus Malan

| Magnus Malan SSA OMSG SD SM MP | |

|---|---|

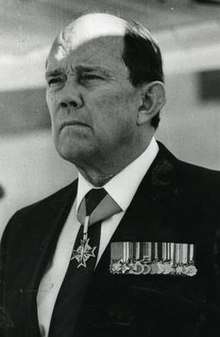

Magnus Malan circa 1990. | |

| Minister of Defence | |

|

In office 1980–1991 | |

| Prime Minister | P. W. Botha |

| Preceded by | P.W. Botha |

| Succeeded by | Roelf Meyer |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Magnus André De Merindol Malan 30 January 1930 Pretoria, South Africa |

| Died |

18 July 2011 (aged 81) Pretoria, South Africa |

| Political party | National |

| Spouse(s) | Magrietha Johanna van der Walt |

| Children | 2 sons, 1 daughter |

| Alma mater | University of Pretoria |

| Occupation | Politician and military chief |

Magnus André de Merindol Malan SSA OMSG SD SM MP (30 January 1930 – 18 July 2011) was a pivotal military man and politician during the last years of apartheid in South Africa. He served respectively as Minister of Defence in the cabinet of President P. W. Botha, Chief of the South African Defence Force (SADF), and Chief of the South African Army. Rising quickly through the lower ranks, he was appointed to strategic command positions. His tenure as chief of the defence force saw it increase in size, efficiency and capabilities.[1] As P.W. Botha's cabinet minister he posited a total communist onslaught, for which an encompassing national strategy was devised. This entailed placing policing, intelligence and aspects of civic affairs under control of generals. The ANC and Swapo were branded as terrorist organizations, while splinter groups (UNITA, RENAMO and LLA) were bolstered in neighbouring and Frontline States.[1] Cross-border raids targeted suspected bases of insurgents or activists, while at home the army entered townships from 1984 onwards to stifle unrest. Elements in the Inkhata Freedom Party were used as a proxy force, and rogue soldiers and policemen in the CCB assassinated opponents.[1]

Personal life

Malan's father was a professor of biochemistry at the University of Pretoria[2] and later a Member of Parliament (1948–1966) and Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees (1961–1966) of the House of Assembly. He started his high school education at the Afrikaanse Hoër Seunskool but later moved to Dr Danie Craven’s Physical Education Brigade in Kimberley, where he completed his matriculation. He wanted to join the South African armed forces immediately after his matric, but his father advised him first to complete his university studies. As a result of this advice, Malan enrolled at the University of Stellenbosch in 1949 to study for a Bachelor of Commerce degree.[3] However, he later abandoned his studies in Stellenbosch and went to University of Pretoria, where he enrolled for a B.Sc. Mil. degree. He graduated in 1953.

In 1962 Malan married Magrietha Johanna van der Walt;[3] the couple had two sons and one daughter.

Military career

At the end of 1949, the first military degree course for officers was advertised and Malan joined the Permanent Force as a cadet, going on to complete his BSc Mil at the University of Pretoria in 1953.[3]

He was commissioned in the Navy and served in the Marines based on Robben Island.[3] When they were disbanded, he was transferred back into the Army as a lieutenant.[4]

Malan was earmarked for high office from early on in his military career; one of the many courses he attended was the Regular Command and General Staff Officers Course in the United States of America from 1962 to 1963. He went on to serve as commanding officer of various formations, including Western Province Command,[5]:95 South West Africa Command, and the South African Military Academy.[5]:95[6]:77

In 1973 he was appointed as Chief of the South African Army and three years later as Chief of the South African Defence Force (SADF).[5]:95[7]:xiv-xv

As Chief of the SADF he implemented many administrative changes that earned him great admiration in military circles.[8] During this period he became very close to P.W. Botha, the then Minister of Defence and later Prime Minister.

Awards and decorations

Malan was awarded the following awards and decorations:[4]

_-_ribbon_bar.gif)

.gif)

Political career

In October 1980 Botha appointed Malan defence minister in the National Party government, a post he held until 1991. As a result of this appointment he joined the National Party and became Member of Parliament for Modderfontein. He was also elected to be a member of the Executive Council of the National Party.[9]

During Malan's tenure in parliament as defence minister his greatest opposition came from MPs of the Progressive Federal Party such as Harry Schwarz and Philip Myburgh, who both served as shadow defence ministers at various points during the 1980s.[10]

In July 1991, following a scandal involving secret government funding to the Inkatha Freedom Party and other opponents of the African National Congress, President F. W. de Klerk removed Malan from his influential post of defence minister and appointed him minister for water affairs and forestry.[11]

The strike craft SAS Magnus Malan of the South African Navy was named after him[12] prior to the change of government in 1994.

Later life

On 2 November 1995, Malan was charged together with 19 other former senior military officers for murdering 13 people (including seven children) in the KwaMakhutha massacre in 1987.[13] The murders were said to have been part of a conspiracy to create war between the African National Congress (ANC) and the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), and maintaining white minority rule. The charges related to an attack in January 1987 on the home of Victor Ntuli, an ANC activist, in KwaMakhutha township near Durban in KwaZulu-Natal.

Malan and the other accused were bailed and ordered to appear in court again on 1 December 1995. A seven-month trial then ensued and brought hostility between black and white South Africans to the fore once again. All the accused were eventually acquitted. President Mandela called on South Africans to respect the verdict.[14] Nonetheless in South Africa, the Malan trial has come to be seen by some as a failure of the legal process.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21]

Malan also had to appear before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[22]

On 26 January 2007, he was interviewed by shortwave/Internet talk radio show The Right Perspective.[23] It is believed to be one of the very few, if not the only, interviews Gen. Malan gave outside of South Africa. In 2006 he published an autobiography titled My Life With the SA Defence Force.[24]

Malan died at his home in Pretoria on 18 July 2011.[25][26] He was survived by his wife, 3 children and 9 grandchildren.[27][3]

Controversy

In August 2018, a book by a former apartheid-era policeman Mark Minnie and journalist Chris Steyn alleged that Malan had been involved in a paedophilia ring in the 1980s.[28] The book, The Lost Boys of Bird Island contains testimony that Malan used his position as Defence Minister to kidnap and ferry young coloured boys to an island off the coast of South Africa by helicopter, under the pretext of going on a fishing trip. They were then allegedly raped and otherwise sexually abused by Malan and other members of the ring who purportedly included local businessman Dave Allen, former minister of environmental affairs John Wiley, and at least one other government minister who is not named but is still alive.[29]

Dave Allen was later arrested for paedophilia but was found dead from an apparent suicide before he was due to appear in court.[30][31] Wiley was found dead just weeks later.[29] Mark Minnie, one of the authors of Lost Boys was found dead from an apparent suicide in August 2018.[32]

These allegations have been met with scepticism and rejection by those who were intimately acquainted with Malan, including his surviving family.[33][34][35]

In a review by investigative journalist Jacques Pauw, Minnie is described as "a sloppy, negligent and careless policeman". Pauw criticised the book's authors, especially Minnie, for the quality of the investigation and research supporting the allegations and Steyn for having a conflict of interest; and asserted that this has had a negative impact on the victims getting justice. [36]

References

- 1 2 3 "Obit – Magnus Malan: monster and militarist". City Press. 23 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ "General Magnus Malan". The Telegraph. Jul 19, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davies, Richard (18 July 2011). "Magnus Malan dies 'peacefully' at 81". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- 1 2 Location Settings (18 July 2011). "Magnus Malan's career". News24. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 Nöthling, C.J.; Meyers, E.M. (1982). "LEIERS DEUR DIE JARE (1912–1982)" (Online). Scientia Militaria – South African Journal of Military Studies (in Afrikaans). 12 (2): 89–98. doi:10.5787/12-2-631. ISSN 2224-0020. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ Uys, Ian (1992). South African Military Who's Who 1452–1992. Germiston: Fortress Publishers. ISBN 0-9583173-3-X.

- ↑ Hamann, Hilton (2001). "Introduction". Days of the Generals. Cape Town: Zebra Press (Struck Publishers). ISBN 1-86872-340-2.

- ↑ Sinclair, Allan (June 2011). "OBITUARY: GENERAL MAGNUS MALAN, 1930 - 2011". South African Military History Journal. 15 (3).

- ↑ Magnus Andre De Merindol Malan, South African History Online, accessed 3 December 2007

- ↑ Roherty, James (1992). State security in South Africa: civil-military relations under P.W. Botha. M E Sharpe Inc. ISBN 0-87332-877-9.

- ↑ Chronology 1990–1999 Archived 1 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine., South African History Online, accessed 3 December 2007

- ↑ Wessels, Andre. "The South African Navy during the years of conflict in Southern Africa 1966–1989" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Mayibuye - Volume 6 No. 8 - December 1995 | African National Congress". www.anc.org.za. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ 1995: Ex-minister charged with apartheid murders, BBC News, accessed 3 November 2006

- ↑ 10 S. Afr. J. Crim. Just. 141 (1997) Failing to Pierce the Hit Squad Veil: An Analysis of the Malan Trial; Varney, Howard; Sarkin, Jeremy

- ↑ 1989 Acta Juridica 165 (1989) Sub-Contracting the Dirty Work; Plasket, Clive

- ↑ Herbert M. Howe (1994). The South African Defence Force and Political Reform. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 32

- ↑ 16 S. Afr. J. on Hum. Rts. 415 (2000) After the Dry White Season: The Dilemmas of Reparation and Reconstruction in South Africa; Jenkins, Catherine

- ↑ The "New" South Africa: Violence Works Bill Berkeley World Policy Journal , Vol. 13, No. 4 (Winter, 1996/1997), pp. 73–80

- ↑ 117 S. African L.J. 572 (2000) Second Bite at the Amnesty Cherry – Constitutional and Policy Issues around Legislation for a Second Amnesty, A; Klaaren, Jonathan; Varney, Howard

- ↑ Shattered voices: language, violence, and the work of truth commissions, Teresa Godwin Phelps. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004 p. 64

- ↑ "PressReader.com - Connecting People Through News". www.pressreader.com. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Baines, Gary. "The life of a uniformed technocrat turned securocrat: My life with the SA Defence Force, Magnus Malan: book review." Historia 54, no. 1 (2009): 314-327.

- ↑ Douglas Martin (18 July 2011). deathsobituaries "Magnus Malan, Apartheid Defender, Dies at 81" Check

|url=value (help). The New York Times. - ↑ "Magnus Malan dies". News24. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ "Magnus Malan dies". News24. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ reporter, Citizen. "Elite ring of apartheid paedophiles allegedly preyed on coloured boys". The Citizen. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- 1 2 "Magnus Malan, two other National Party ministers 'were paedophiles'". News24. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- ↑ "Apartheid's paedophiles: 'Magnus Malan and others in sex orgies with young boys'". CityPress. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- ↑ "Police issue warning on cabinet member's suicide". UPI. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- ↑ Wilson, Gareth (14 August 2018). "Apartheid paedophile ring: Suicide note found at scene where Mark Minnie's body found". Times Live. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018.

- ↑ "Magnus se familie 'geweldig geskok'". Netwerk24 (in Afrikaans). Retrieved 2018-08-07.

- ↑ "Magnus se familie verwerp bewering 'ten sterkste'". Netwerk24 (in Afrikaans). Retrieved 2018-08-07.

- ↑ "'Loutere kaf, sê Pik oor bewerings oor Malan". Beeld (in Afrikaans). Retrieved 2018-08-07.

- ↑ "Mark Minnie: A sloppy, negligent and careless policeman".

External links

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Pieter Willem Botha |

Minister of Defence (South Africa) 1980–1991 |

Succeeded by Roelf Meyer |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by Hugo Biermann |

Chief of the South African Defence Force 1976–1980 |

Succeeded by Constand Viljoen |

| Preceded by Willem Louw |

Chief of the South African Army 1973–1976 |

Succeeded by Constand Viljoen |

| Preceded by Jan Fourie |

OC Western Province Command 1971–1972 |

Succeeded by Helm Roos |

| Preceded by Col Pieter J.G. "Vlakkies" de Vos |

OC South African Military Academy 1967–1971 |

Succeeded by Johan D. Potgieter |