Magic Kingdom

Cinderella Castle, the icon of Magic Kingdom | |

| Slogan | The Most Magical Place on Earth |

|---|---|

| Location | Walt Disney World Resort, Bay Lake, Florida, United States |

| Coordinates | 28°25′07″N 81°34′52″W / 28.41861°N 81.58111°W |

| Theme | Fairy tales and Disney characters |

| Owner | The Walt Disney Company |

| Operated by | Walt Disney Parks, Experiences and Consumer Products |

| Opened | October 1, 1971 |

| Previous names |

The Magic Kingdom Walt Disney World Magic Kingdom (1971-1990s) |

| Operating season | Year-round |

| Website | Official website |

| Walt Disney World |

|---|

| Theme parks |

| Water parks |

| Other attractions |

| Hotels |

Magic Kingdom is a theme park at the Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida, near Orlando. Owned and operated by The Walt Disney Company through its Parks, Experiences and Consumer Products division, the park opened on October 1, 1971, as the first of four theme parks at the resort. Initialized by Walt Disney and designed by WED Enterprises, its layout and attractions are based on Disneyland Park in Anaheim, California, and is dedicated to fairy tales and Disney characters.

The park is represented by Cinderella Castle, inspired by the fairy tale castle seen in the 1950 film. In 2017, the park hosted 20.450 million visitors, making it the most visited theme park in the world for the twelfth consecutive year and the most visited theme park in North America for at least the past eighteen years.[1]

History

Roy O. Disney, October 25, 1971[2][3]

Although Walt Disney had been highly involved in planning the Florida Project, he passed away before he could see the vision through. After Walt's death, Walt Disney Productions began construction on Magic Kingdom and the entire resort in 1967. The park was built as a larger, improved version of Disneyland Park in California. There are several anecdotes regarding some of the features of Walt Disney World, and Magic Kingdom specifically. According to one story, Walt Disney once saw a Frontierland cowboy walking through Tomorrowland at Disneyland. He disliked that the cowboy intruded on the futuristic setting of Tomorrowland and wanted to avoid situations like this in the new park.[4] Therefore, Magic Kingdom was built over a series of tunnels called utilidors, a portmanteau of utility and corridor, allowing employees (called "cast members") or VIP guests to move through the park out of sight from guests.

Because of Florida's high water table, the tunnels could not be put underground, so they were built at the existing grade, meaning the park is built on the second story, giving Magic Kingdom an elevation of 108 feet (33 m). The area around the utilidors was filled in with dirt removed from the Seven Seas Lagoon, which was being constructed at the same time. The utilidors were built in the initial construction and were not extended as the park expanded. The tunnels were intended to be designed into all subsequent Walt Disney World parks, but were set aside mostly because of financial constraints. Future World at Epcot and Pleasure Island each have a smaller network of utilidors.

Magic Kingdom opened as the first part of the Walt Disney World Resort on October 1, 1971, commencing concurrently with Disney's Contemporary Resort and Disney's Polynesian Village Resort. It opened with twenty-three attractions, three unique to the park and twenty replicas of attractions at Disneyland, split into six themed lands, five copies of those at Disneyland (Main Street, U.S.A., Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland) and the Magic Kingdom exclusive of Liberty Square. The Walt Disney Company promised to increase this number with a combination of replicas and unique attractions. While there is no individual dedication to Magic Kingdom, the dedication by Roy O. Disney for the entire resort was placed within its gates.

The first, and as of today, only land added to the original roster of lands in the park was Mickey's Toontown Fair. The land originally opened in 1988 as Mickey's Birthdayland to celebrate Mickey Mouse's 60th birthday. Later the land was renovated as Mickey's Starland and eventually to Mickey's Toontown Fair. The land was home to attractions such as Mickey's Country House, Minnie's Country House, The Barnstormer at Goofy's Wiseacre Farm, and Donald's Boat. It closed on February 12, 2011, to make way for the expansion of Fantasyland. The Walt Disney World Railroad station in Mickey's Toontown Fair, which opened with Mickey's Birthdayland in 1988, was closed for the duration of the construction. In 2012, the space where Mickey's Toontown Fair sat reopened as a part of Fantasyland, in a sub-land called the Storybook Circus, where the Dumbo the Flying Elephant was relocated. The Barnstormer was retained and was re-themed to The Great Goofini.[5]

Since opening day, Magic Kingdom has been closed temporarily because of seven hurricanes: Floyd, Charley, Frances, Jeanne, Wilma, Matthew, and Irma.[6] The only non-hurricane related day the park has closed is on September 11, 2001, due to the terrorist attacks that day.[7] In addition, there are four "phases" of park closure when Magic Kingdom exceeds capacity, ranging from restricted access for most guests (Phase 1) to full closure for everyone, even cast members (Phase 4).[8]

"Magic Kingdom" was often used as an unofficial nickname for Disneyland before Walt Disney World was built. The official tagline for Disneyland is "The Happiest Place On Earth", while the tagline for Magic Kingdom is "The Most Magical Place On Earth". Up until the early 1990s, Magic Kingdom was officially known as Walt Disney World Magic Kingdom, and was never printed without the Walt Disney World prefix. This purpose was to differentiate between the park and Disneyland in California, which was and is also commonly referred to as the Magic Kingdom. In 1994, to differentiate it from Disneyland, the park was officially renamed Magic Kingdom Park, but is still known as Magic Kingdom or sometimes The Magic Kingdom. Like all Disney theme parks, the official name of the park does not start with an article ("the"), though it is commonly referred to that way; however, a sign on the railroad station at the front of the park reads "Magic Kingdom".

Alcoholic beverages had been prohibited from the park since its opening, but this policy has changed in recent years. In 2012, the Be Our Guest restaurant opened selling wine and beer for the first time. This was the only place in the park where alcohol was permitted until December 2016 when four additional restaurants began selling beer and wine including Cinderella's Royal Table, Liberty Tree Tavern, Tony's Town Square Restaurant, and the Jungle Navigation Co. Ltd. Skipper Canteen.[9][10] And finally in 2018, the park officially became the second Magic Kingdom-style park to serve alcohol at all table service restaurants, after Disneyland Paris in 1993.[11]

Lands

Magic Kingdom is divided into six themed "lands." It is designed like a wheel, with the hub in front of Cinderella Castle. Pathways spoke out from the hub across the 107 acres (43 ha) of the park and lead to these six lands.[12] The 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge Walt Disney World Railroad circles around the entire 1.5-mile (2.4 km) perimeter of the park and makes stops at Main Street, U.S.A., Frontierland, and Fantasyland.[13] One of the world's busiest steam-powered railroads, it transports 3.7 million passengers each year.[13] The railroad has four steam locomotives, No. 1 Walter E. Disney (a 4-6-0 Ten-wheeler), No. 2 Lilly Belle (a 2-6-0 Mogul), No. 3 Roger E. Broggie (another 4-6-0 Ten-wheeler) and No. 4 Roy O. Disney (a 4-4-0 American).[13][14]

- Lands of the Magic Kingdom

Adventureland

Adventureland

(exterior of Tortuga Tavern)

.jpg)

Fantasyland

Fantasyland

(Bavarian theming)

Main Street, U.S.A.

Symbolically, Main Street, U.S.A. represents the park's "opening credits," where guests pass under the train station (the opening curtain), then view the names of key personnel along the windows of the buildings' upper floors. Many windows bear the name of a fictional business, such as "Seven Summits Expeditions, Frank G. Wells President", with each representing a tribute to significant people connected to the Disney company and the development of the Walt Disney World Resort. It features stylistic influences from around the country. Taking its inspiration from New England to Missouri, this design is most noticeable in the four corners in the middle of Main Street, where each of the four corner buildings represents a different architectural style. There is no opera house as there is at Disneyland; instead, there is the Town Square Theater. Christopher George Weaver, the "mayor" of Main Street U.S.A. and one of the park's most important figures, greeted guests here for 26 years before he passed away in 2017. [15]

Main Street is lined with shops selling merchandise and food. The decor is early-20th century small-town America, inspired by Walt Disney's childhood and the film Lady and the Tramp. City Hall contains the Guest Relations lobby, where cast members provide information and assistance. A working barber shop gives haircuts for a fee. The Emporium carries a wide variety of Disney souvenirs such as plush toys, collectible pins and Mickey-ear hats. Tony’s Town Square Restaurant and The Plaza Restaurant are table-service locations. At the end of Main Street is Casey's Corner, where guests enjoy traditional American ballpark fare including hot dogs and fries while enjoying old baseball tunes on the piano. The Main Street Confectionery sells sweets priced by their weight, such as candied apples, crisped rice treats, chocolates, cookies and fudge.[16] Most windows bear the name of people who were influential at Disney parks. An example of a classic Main Street, U.S.A. attraction is the 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge Walt Disney World Railroad, which transports guest throughout the park, making stops at Main Street, U.S.A., Fantasyland, and Frontierland. The railroad's previous stop at Mickey's Toontown Fair was replaced by the Fantasyland stop in 2012 . Main Street, U.S.A. also has the Main Street Vehicles attraction, which includes a 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge[17] tramway with horse-drawn streetcars, and several old-fashioned motor vehicles.

In the distance beyond the end of Main Street stands Cinderella Castle. Though only 189 feet (58 m) tall, it benefits from a technique known as forced perspective. The second stories of all the buildings along Main Street are shorter than the first stories, and the third stories are even shorter than the second, and the top windows of the castle are much smaller than they appear. The resulting visual effect is that the buildings appear to be larger and taller than they really are.

The park contains two additional tributes: the Partners statue of Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse in front of Cinderella Castle and the Sharing the Magic statue of Roy O. Disney sitting with Minnie Mouse in the Town Square section of Main Street, U.S.A. Both were sculpted by veteran Imagineer Blaine Gibson. In 2012, Disney replaced the shop in the Firehouse with a sign up for the Sorcerers of the Magic Kingdom game.

Adventureland

Adventureland represents the mystery of exploring foreign lands. It is themed to resemble the remote jungles in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, South America and the South Pacific, with an extension resembling a Caribbean town square. It contains classic attractions such as Pirates of the Caribbean, the Jungle Cruise, Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room, the Swiss Family Treehouse, and The Magic Carpets of Aladdin.

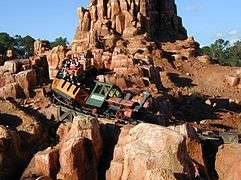

Frontierland

In Frontierland guests can relive the American Old West, from the romanticized cowboys and Native Americans, to exploring the mysteries of the Rivers of America. It contains classic attractions such as Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, Splash Mountain, and the Country Bear Jamboree. The land also contains shops such as Big Al's, Frontier Trading Post, Prairie Outpost and Supply, Briar Patch, and Splashdown Photos. Walt Disney World's Festival of Fantasy Parade begins in Frontierland and makes its way through several lands, eventually ending on Main Street, U.S.A., toward the front of the park.

Liberty Square

Liberty Square is inspired by a colonial American town set during the American Revolution. The Liberty Belle Riverboat travels down the park's Rivers of America. Liberty Square is home to such attractions as the Haunted Mansion, the Hall of Presidents, and The Muppets Present...Great Moments in American History. A sign-up location for the Sorcerers of the Magic Kingdom is behind the Christmas shop.

Fantasyland

Fantasyland is themed in a medieval-faire/carnival style, in the words of Walt Disney: "Fantasyland is dedicated to the young at heart and to those who believe that when you wish upon a star, your dreams come true." Attractions include It's a Small World, Peter Pan's Flight, The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, Mickey's PhilharMagic, Prince Charming Regal Carrousel, and Mad Tea Party. From 2012 to 2014, Fantasyland was expanded to nearly double its size and new attractions and guest offerings were added, including sub-areas themed to Beauty and the Beast, Tangled, and The Little Mermaid. New attractions such as the Seven Dwarfs Mine Train and Under the Sea: Journey of the Little Mermaid were introduced.

Castle Courtyard

The original Fantasyland attractions left after the expansion was completed are located within the castle walls this courtyard area directly behind Cinderella Castle. Attractions here include: Mickey's PhilharMagic, Prince Charming Regal Carrousel, Princess Fairytale Hall, It's a Small World, Peter Pan's Flight, Mad Tea Party and The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh.

Storybook Circus

Part of Fantasyland, Storybook Circus is located at the former site of Mickey's Toontown Fair, and is based on elements from Dumbo and the Mickey Mouse universe. Attractions include The Barnstormer and Dumbo the Flying Elephant, which was removed from its former location on January 8, 2012. Also included is the Casey Jr. Splash n' Soak Station (a water play area themed to Casey Jr., the train from Dumbo). Storybook Circus began soft openings on March 12, 2012, with more parts opening on March 31.

Mickey's Toontown Fair closed permanently on February 11, 2011, to make way for Storybook Circus. Some elements of Mickey's Toontown Fair were demolished, and others were re-themed to fit the circus concept. An expanded Dumbo the Flying Elephant ride was built, with an interactive queue, and a second Dumbo ride was built next to it, in order to increase capacity. The Barnstormer at Goofy's Wiseacre Farm was re-themed to "The Great Goofini". A big top area was built for meet-and-greets, called Pete's Silly Sideshow. This attraction features Goofy as a stuntman, Minnie as a magician, Daisy as a fortune-teller, and Donald as a snake-charmer.

Enchanted Forest

The completion of the Enchanted Forest section of the park concluded the expansion of New Fantasyland.[18] Included in the expansion was the attraction Under the Sea ~ Journey of the Little Mermaid, themed to Disney's 1989 film The Little Mermaid. The attraction is a near replica of the Disney California Adventure attraction, The Little Mermaid, Ariel's Undersea Adventure. There is also an area themed to Disney's 1991 film Beauty and the Beast, featuring the Beast's Castle with the dining experience Be Our Guest Restaurant (offering quick-service lunches and table service dinners), as well as Gaston's Tavern and Belle's cottage.[19] This portion of the New Fantasyland officially opened on December 6, 2012. Snow White's Scary Adventures was removed to build Princess Fairytale Hall, a meet-n-greet. Another attraction themed to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs called the Seven Dwarfs Mine Train opened in 2014. The attraction, which features Snow White's cottage and state of the art audio-animatronics, is the first roller coaster to move in a wobbling motion on track.[19]

Tomorrowland

Tomorrowland is set in an intergalactic city, a concept of the future as seen from around the 1950s: rockets, UFOs and robots, etc. In the words of Walt Disney: "Tomorrow can be a wonderful age. Our scientists today are opening the door of the Space Age to achievements that will benefit our children and generations to come. The Tomorrowland attractions have been designed to give you an opportunity to participate in adventures that are a living blueprint of our future." Classic attractions include Space Mountain, Walt Disney's Carousel of Progress, Astro Orbiter, Tomorrowland Transit Authority PeopleMover and the Tomorrowland Speedway. Other current attractions include Stitch's Great Escape!, Buzz Lightyear's Space Ranger Spin, and Monsters, Inc. Laugh Floor. The TRON Lightcycle Power Run roller coaster from Shanghai Disneyland will be opening to the north of Space Mountain in a new area of Tomorrowland, and it will be open before Disney World's 50th anniversary in 2021.[20][21][22]

Transportation and Ticket Center

Magic Kingdom lies more than a mile away from its parking lot, on the opposite side of the man-made Seven Seas Lagoon. Upon arrival, guests are taken by the parking lot trams to the Transportation and Ticket Center (TTC), which sells admission into the parks and provides transportation connections throughout the resort complex.

To reach the park, guests either use the Walt Disney World Monorail System, the ferryboats, or Disney Transport buses, depending on the location of their hotel or parking lot. The three hotels closest to Magic Kingdom, Disney's Contemporary Resort, Disney's Polynesian Village Resort, and Disney's Grand Floridian Resort and Spa, use either the ferry or monorail system to travel to Magic Kingdom. Guests staying at Disney's Wilderness Lodge and Disney's Fort Wilderness Campground can also ride a dedicated ferry boat to the Magic Kingdom docks. Guests of other hotels take buses to travel to the park, while guests who are not staying at any of the resort's hotels must use the monorail system or ferryboats to travel to the park from the Transportation and Ticket Center. The three ferries are clad in different trim colors and are named for past Disney executives: the General Joe Potter (blue), the Richard F. Irvine (red) and the Admiral Joe Fowler (green). The main monorail loop has two lanes. The outer lane is a direct nonstop loop between the TTC and Magic Kingdom, while the inner loop has additional stops at Disney's Contemporary Resort, Disney's Polynesian Village Resort, and Disney's Grand Floridian Resort & Spa. Epcot is accessible by a spur monorail line that was added upon that park's opening in 1982.

| Preceding station | Walt Disney World Monorail | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

One-way operation | Resort Line Magic Kingdom continuous loop clockwise | Next clockwise |

||

Next counterclockwise | Express Line Magic Kingdom continuous loop counterclockwise | One-way operation |

Attendance

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15,400,000[23] | 14,700,000[24] | 14,000,000[25] | 14,040,000[26] | 15,100,000[27] | 16,100,000[28] | 16,640,000[29] | 17,060,000[30] | 17,063,000[31] | 17,233,000[32] |

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Worldwide rank | |

| 16,972,000[33] | 17,142,000[34] | 17,536,000[35] | 18,588,000[36] | 19,332,000[37] | 20,492,000[38] | 20,395,000[39] | 20,450,000[1] | 1 |

Planned film

In 2012, Jon Favreau announced he was planning a film called Magic Kingdom.[40] The film is described as “Night at the Museum at Disneyland,” meaning that the film would tell a story where all the characters at Disney come to life at night.[40] Marc Abraham and Eric Newman of Strike Entertainment were scheduled to produce the film.[41] Writer-producer Ronald D. Moore had previously written an original script for the project, which the studio eventually declined to use, stating that Favreau and a new screenwriter would develop a new script.[41] As of 2014, Favreau was directing the 2016 adaptation of The Jungle Book, but still expressed interest in pursuing the project.[42]

In popular culture

- Adventures in the Magic Kingdom, a 1990 video game for the Nintendo Entertainment System

- Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, a 2003 science fiction novel by Cory Doctorow

- The Kingdom Keepers, a 2005 children's novel by Ridley Pearson

- The Florida Project, a 2017 drama film by Sean Baker

See also

References

- 1 2 Au, Tsz Yin (Gigi); Chang, Bet; Chen, Bryan; Cheu, Linda; Fischer, Lucia; Hoffman, Marina; Kondaurova, Olga; LaClair, Kathleen; Li, Shaojin; Linford, Sarah; Marling, George; Miller, Erik; Nevin, Jennie; Papamichael, Margreet; Robinett, John; Rubin, Judith; Sands, Brian; Selby, William; Timmins, Matt; Ventura, Feliz; Yoshii, Chris (May 17, 2018). "TEA/AECOM 2017 Theme Index & Museum Index: Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). aecom.com. Themed Entertainment Association. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Magic Kingdom 1971 Grand Opening (Video)". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Sklar, Martin (August 13, 2013). Dream It! Do It!: My Half-Century Creating Disney's Magic Kingdoms. Disney Electronic Content. ISBN 9781423184522. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ↑ Dening, Lizzy (January 7, 2014). "What lies beneath: Going underground to uncover Disney World's secrets". Mail Online.

- ↑ Smith, Thomas (December 10, 2010). "New Fantasyland Expansion Update". Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ Pedicini, Sandra. "Disney World closing early today as Hurricane Matthew approaches". OrlandoSentinel.com. Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Magic Kingdom". Disney Reporter. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011.

- ↑ Cassie (January 5, 2014). "What Happens When A Disney Park Is Closed Due to Reaching Capacity?". DisneyDining. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Disney to serve alcohol at the Magic Kingdom Park". CNN. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Once alcohol-free, Disney's Magic Kingdom to expand beer, wine sales". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Walt Disney World's Magic Kingdom Will Now Serve Alcohol In All Restaurants". Inquisitr. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Magic Kingdom Theme Park - Walt Disney World Resort". Walt Disney World.

- 1 2 3 Grant, Rich (March 18, 2015). "How Walt Disney's Love of Trains Changed the World". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ↑ Broggie (2014), pp. 393–394.

- ↑ Kubersky, Seth. "Christopher George Weaver, the 'Mayor of Main Street USA,' passes away". Attractions Magazine. Attractions Magazine. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ "Main Street Confectionery, Magic Kingdom". Walt Disney World. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Trams of the World 2017" (PDF). Blickpunkt Straßenbahn. January 24, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Thomas (January 18, 2011). "Update on New Fantasyland at Magic Kingdom Park". Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- 1 2 "Disney World's Fantasyland expansion". WOFL FOX 35. January 18, 2011. Archived from the original on January 21, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- ↑ Smith, Thomas. "New Tron Attraction Coming to Magic Kingdom Park at Walt Disney World Resort". Disney Parks Blog. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ Lambert, Marjie. "4 new rides coming to Disney World: Ratatouille, Tron, Mickey Mouse, Guardians of the Galaxy". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ Bevil, Dewayne. "Coming to Disney World: Tron, Guardians of the Galaxy ride, 'Star Wars' hotel". OrlandoSentinel.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Park Attendance Rose In 2000 For Many Amusement Parks". Ultimaterollercoaster.com. January 1, 2001. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2017.

- ↑ "Amusement Business/ERA 2001 North American Theme Park Attendance Figures". Amusement Business/ERA. 2001. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Amusement Business/ERA 2002 North American Theme Park Attendance Figures". Amusement Business/ERA. 2002. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Amusement Business/ERA 2003 North American Theme Park Attendance Figures". Amusement Business/ERA. 2003. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Amusement Business/ERA 2004 North American Theme Park Attendance Figures". Amusement Business/ERA. 2004. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Amusement Business/ERA 2005 North American Theme Park Attendance Figures". Amusement Business/ERA. 2005. Archived from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/ERA 2006 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/ERA. 2007. p. 4. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/ERA 2007 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/ERA. 2008. p. 7. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/ERA 2008 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/ERA. 2009. p. 7. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/AECOM 2009 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2010. p. 7. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/AECOM 2010 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2011. p. 23. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/AECOM 2011 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2012. p. 7. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/AECOM 2012 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2013. p. 9. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/AECOM 2013 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2014. p. 7. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/AECOM 2014 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2015. p. 7. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "TEA/AECOM 2015 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2016. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ↑ Au, Tsz Yin (Gigi); Chang, Bet; Chen, Bryan; Cheu, Linda; Fischer, Lucia; Hoffman, Marina; Kondaurova, Olga; LaClair, Kathleen; Li, Shaojin; Linford, Sarah; Marling, George; Miller, Erik; Nevin, Jennie; Papamichael, Margreet; Robinett, John; Rubin, Judith; Sands, Brian; Selby, William; Timmins, Matt; Ventura, Feliz; Yoshii, Chris (June 1, 2017). "TEA/AECOM 2016 Theme Index & Museum Index: Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). aecom.com. Themed Entertainment Association. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- 1 2 Topel, Fred (July 25, 2015). "Pixar is Helping with Jon Favreau's 'Magic Kingdom". Crave Online. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015.

- 1 2 Graser, Marc. "Jon Favreau enters Disney's 'Magic Kingdom'", Variety, November 10, 2010. WebCitation archive.

- ↑ "Jon Favreau Still Wants To Do 'Magic Kingdom'; Could Be After 'Jungle Book' - /Film". Slashfilm. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014.

Bibliography

- Broggie, Michael (2014). Walt Disney's Railroad Story: The Small-Scale Fascination That Led to a Full-Scale Kingdom (4th ed.). The Donning Company Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57864-914-3.

External links

Coordinates: 28°25′07″N 81°34′52″W / 28.41861°N 81.58111°W