Lynchburg Sesquicentennial half dollar

| United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1936 |

| Mintage | 20,000 with 13 pieces for the Assay Commission |

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at the Philadelphia Mint without mint mark |

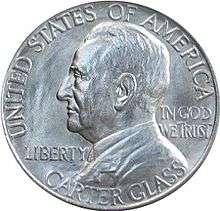

| Obverse | |

| |

| Design | Bust of Carter Glass |

| Designer | Charles Keck |

| Design date | 1936 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Liberty |

| Designer | Charles Keck |

| Design date | 1936 |

The Lynchburg Sesquicentennial half dollar was a commemorative half dollar, designed by Charles Keck, minted by the United States Bureau of the Mint in 1936. The obverse side of the coin depicts former Secretary of the Treasury and U.S. Senator Carter Glass, who was a native of Lynchburg. The reverse depicts a statue of the goddess Liberty, with Lynchburg sites behind her, including the city's Confederate monument.

Glass sponsored legislation for the half dollar, which passed Congress without difficulty. The Commission of Fine Arts proposed that ting that the coin should bear the portrait of John Lynch, founder of Lynchburg, on the obverse, but no portrait of him was known. Instead, the Lynchburg Sesqui-Centennial Association decided Senator Glass should be on the coin. Despite his opposition, this occurred, making him Glass the third living person to appear on a U.S. coin, and the first to be depicted alone.

The coins sold well when placed on sale in late summer 1936, and sales to out-of-towners were limited. The entire issue sold out, with some placed aside for sale at the sesquicentennial celebrations in October. Issued for $1, the coins have appreciated over the years, with 2018 estimates of value ranging between $225 and $365, depending on condition.

Background

The Lynchburg Sesqui-Centennial Association desired to have a commemorative half dollar honoring the anniversary of the Virginia General Assembly's recognizing Lynchburg as an incorporated municipality in 1786; it became a city in 1852.[1] In so doing, they were motivated by local pride, rather than the greediness that provoked some commemorative coin issues of the era.[2] Lynchburg was a supply center for the Confederacy during the Civil War; a Union attempt to take the city was beaten back in 1864 by Confederate General Jubal Early. In 1858, Carter Glass, later Secretary of the Treasury and a representative and senator from Virginia, was born there, and lived there in 1936.[3]

In 1936, commemorative coins were not sold by the government—Congress, in authorizing legislation, usually designated an organization which had the exclusive right to purchase them at face value and vend them to the public at a premium.[4] In the case of the Lynchburg half dollar, the responsible group was the Sesqui-Centennial Assocition.[5] Profits from the sale of coins were to defray the cost of the anniversary celebrations.[6]

Legislation

Glass introduced the bill for a Lynchburg Sesquicentennial half dollar in the Senate on April 8, 1936; it was referred to the Committee on Banking and Currency. On April 22, Alva B. Adams of Colorado reported it back to the Senate.[7] In its report, the committee noted that the bill included the standardized language it advocated because of past commemorative coin abuses: including that they be issued at only one mint, and that no fewer than 5,000 be issued at a time, have only one design, be struck within a year of enactment, and bear the date 1936 even if struck later. The committee recommended the bill pass.[8]

On April 24, Adams brought the bill before the Senate, and moved that the authorized quantity of the coins be increased from 10,000 to 20,000. Both the amendment and the bill were agreed to without debate or recorded opposition.[9] The bill then went to the House of Representatives where on May 22, Virginia's Clifton A. Woodrum brought it to the floor. Robert F. Rich of Pennsylvania, a Republican, took the floor long enough to note that "this is, perhaps, the thirtieth bill of this kind to come in here this session of Congress. It is surely the beginning of Democratic inflation, and I warn the Members of the House to beware."[10] Following laughter and applause, the bill passed,[10] and became the Act of May 28, 1936, authorizing 20,000 half dollars, with the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[5]

Preparation

On May 25, 1936, with the Lynchburg bill close to enactment, the secretary of the Sesqui-Centennial Association, Fred McWane, wrote to Charles S. Moore, chairman of the federal Commission of Fine Arts.[11] The commission was charged by a 1921 executive order by President Warren G. Harding with rendering advisory opinions regarding public artworks, including coins.[12] Moore replied on the 26th, suggesting that the coin should bear the portrait of John Lynch, founder of Lynchburg, on the obverse. McWane replied the following day, stating that there was no known portrait of Lynch, and that the Sesqui-Centennial Association was considering other possible obverses. For the reverse, McWane proposed the city's Memorial Terrace, long the first sight there that greeted visitors arriving by rail.[13]

On June 3, McWane wrote stating that the Sesqui-Centennial Association was considering Charles Keck and John David Brcin to sculpt the coin; Moore in his reply on the 9th, praised both men, but praised Keck more.[14] Keck had designed the 1915 Panama-Pacific gold dollar and the Vermont Sesquicentennial half dollar in 1927.[15] The Sesquicentennial Commission took the hint and McWane notified Moore of Keck's hiring on July 1. He also advised Moore that his commission had decided Senator Glass should appear on the obverse.[14]

Glass protested at the idea of his face appearing on a coin, but this was to no avail. He telephoned the Philadelphia Mint in the hope a law might forbid himself, as a living person, from appearing on a coin, but was told that none did. The senator stated, "I had hoped there would be an avenue of escape."[16] According to Don Taxay in his volume on U.S. commemorative coins, Glass "though the most influential man in Lynchburg, and honorary president of the Sesquicentennial Association, he found himself hopelessly outvoted".[11] On July 28, Mary Margaret O'Reilly, the Assistant Director of the Mint, forwarded Keck's models to the Fine Arts Commission; they were approved the following day.[17] Moore wrote to Glass on the 31st, predicting that the senator's depiction was one "that both your friends and posterity will approve".[14]

Design

The obverse depicts Senator Carter Glass. In so doing, the Lynchburg Sesquicentennial half dollar became the third U.S. coin to depict a living person, and the first to depict one alone—the earlier two (the Alabama Centennial half dollar (1921) and the U.S. Sesquicentennial half dollar depict jugate busts of a living person, a governor or president, with a deceased predecessor).[18] Glass also became the first person to have his signature on U.S. currency (during his term as Treasury Secretary) and his portrait on a coin.[2]

The reverse depicts a statue of the goddess Liberty, her arms outstretched in welcome. In the background is seen a portion of Monument Terrace, with the Old Lynchburg Courthouse also depicted. Before the building is the city's Confederate monument.[19] According to Anthony Swiatek in his 2012 volume on commemorative coins, "the Confederacy receives prominent recognition on this coin".[20] Amid the debate over the removal of Confederate monuments in the United States, the question of whether to remove that statue, dedicated in 1900, has been raised, but as of 2017, it remains in place.[21]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule, in his volume on U.S. commemorative coins and medals, deemed Keck's half dollar, "a successful but not startling combination of conservative elements".[22] He described the figure of Liberty on the reverse as "a Greco-Roman, actually Greek imperial, frontal Liberty placed before local landmarks".[22] Vermeule suggested that the tall, thin lettering on the reverse indicates that Keck was less influenced by his Augustus Saint-Gaudens, under whom he studied, than by the Chief Engraver of the United States Mint Charles E. Barber (served 1880–1917) and his successor George T. Morgan (1917–1925), tying the Liberty to coins and medals designed by the two, including their work on medals for the Assay Commission. He concluded that Keck's "style, as manifest in the Lynchburg Sesquicentennial half-dollar, was a recollection of the fashions perpetuated by Barber and Morgan".[23]

Production, distribution and collecting

In September 1936, the Philadelphia Mint struck 20,000 Lynchburg half dollars, plus 13 extra that would be held for inspection and testing at the 1937 meeting of the annual Assay Commission. They came on the market during a price boom in commemorative coins, and readily sold at a price of $1 each. There was an order limit of 10 per person, though this might be waived if there was a written explanation.[24] Orders were accepted in advance, and the August 1936 issue of The Numismatist (the journal of the American Numismatic Association) contained a statement from the Sesqui-Centennial Association that orders for 2,000 had been received.[25] Once 15,000 had been sold, the remainder was held to allow local residents the opportunity to buy them.[26] On September 2, McWane wrote to a potential out-of-state purchaser stating that they had all been purchased.[27] They were formally placed on sale on September 21.[24] Some were put aside for sale at the sesquicentennial celebration, held in Lynchburg from October 12 to 16, where they sold, mainly to local residents.[28]

The coins increased in price after 1936, their value helped by the wide distribution of the mintage, with no known hoards. By 1940, the value in uncirculated condition was $2, and by 1970 $40. At the height of the second commemorative coin boom in 1980, they sold for $550, dropping back to $375 by 1985.[29] The deluxe edition of R. S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins, published in 2018, lists the coin for between $225 and $365, depending on condition.[30] An exceptional specimen sold in 2008 for $4,830.[6]

References

- ↑ Taxay, p. 212.

- 1 2 Swiatek & Breen, p. 144.

- ↑ Slabaugh, pp. 124–25.

- ↑ Slabaugh, pp. 3–5.

- 1 2 Flynn, p. 355.

- 1 2 Flynn, p. 118.

- ↑ S. 448 Calendar No. 2009. United States Senate. April 22, 1936.

- ↑ Senate Committee on Banking and Commerce (April 22, 1936). Authorize the Coinage of 50-cent Pieces in Commemoration of the One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Issuance of the Charter to the City of Lynchburg, Va. p. 1.

- ↑ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 6067 (April 24, 1936)

- 1 2 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Pages 7774–75 {May 22, 1936)

- 1 2 Taxay, p. 211.

- ↑ Taxay, pp. v–vi.

- ↑ Taxay, pp. 212, 214.

- 1 2 3 Taxay, p. 214.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 376.

- ↑ Swiatek, p. 351.

- ↑ Taxay, p. 216.

- ↑ Swiatek, pp. 251–352.

- ↑ Slabaugh, p. 24.

- ↑ Swiatek, p. 352.

- ↑ Louissaint, Magdala (August 17, 2017). "Lynchburg City to Discuss Whether to Keep or Take Down Confederate Statue". WSLS. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- 1 2 Vermeule, p. 196.

- ↑ Vermeule, pp. 196–97.

- 1 2 Bowers, pp. 26, 376.

- ↑ "The Lynchburg (Va.) Half Dollar". The Numismatist. August 1936. p. 660.

- ↑ Horner, John V. (October 1936). "The Lynchburg Half Dollar". The Numismatist. p. 828.

- ↑ Swiatek, pp. 352,354.

- ↑ Swiatek & Breen, p. 376.

- ↑ Bowers, pp. 376–77.

- ↑ Yeoman, p. 1086.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago, IL: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins 2014 (Mega Red 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.

External links