Old Spanish Trail half dollar

| United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1935 |

| Mintage | 10,000 with 8 pieces for the Assay Commission |

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at the Philadelphia Mint without mint mark |

| Obverse | |

| |

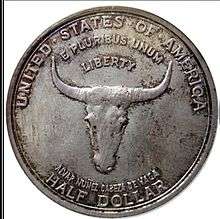

| Design | The head of a cow |

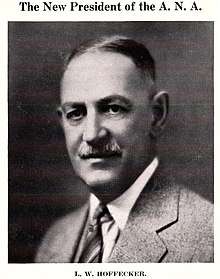

| Designer | L.W. Hoffecker |

| Design date | 1935 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Yucca plant superimposed on map of the Gulf Coast states. |

| Designer | L.W. Hoffecker |

| Design date | 1935 |

The Old Spanish Trail half dollar was designed by L.W. Hoffecker and minted in 1935.

Background

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was an officer on a Spanish expedition that landed around Tampa Bay in 1528. Their searches for treasure led to a hostile reception by the local Native Americans, and de Vaca was eventually marooned there. He and others made their way west by small boats along the coast, and eventually reached Galveston Island, where he lived with the Karankawa tribe as a medicine man before continuing west overland: in 1536 he found a Spanish patrol in northern Mexico. He returned home and wrote of his experiences.[1] Cabeza de Vaca, or "head of a cow" was a name said to have been given by the King of Spain to an ancestor for his help guiding the army through the mountains, enabling an attack on the Moors from the rear, defeating them.[2] Cabeza de Vaca's route later came to be known as the Old Spanish Trail, though his exact path is uncertain.[3]

In the 1930s, commemorative coins were not sold by the government—Congress, in authorizing legislation, usually designated an organization which had the exclusive right to purchase them at face value and vend them to the public at a premium.[4] In the case of the Old Spanish Trail half dollar, the responsible group was the El Paso Museum, acting through its chairman.[5]

Lyman William Hoffecker (usually known as L.W. Hoffecker) was an El Paso, Texas coin dealer and an official of the American Numismatic Association (ANA);[6] he would serve as its president from 1939 to 1941. In 1929, he organized the Gadsden Purchase Commission (consisting mostly of himself) to seek a commemorative coin issue for the 75th anniversary of the Gadsden Purchase. A bill that would have authorized one passed both houses of Congress in 1930, but it was vetoed by President Herbert Hoover. Undiscouraged by this, Hoffecker made a second attempt for a commemorative coin issue he would control in 1935, for the Old Spanish Trail, becoming chairman of the El Paso Museum Coin Committee. This time, he visited Washington and had discussions with a number of lawmakers, and was even granted a five-minute interview with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a talk Hoffecker said "that saved us".[7] Hoffecker later testified before Congress that he was asked to handle the arrangements of the Old Spanish Trail half dollar as the only coin collector in El Paso, something Q. David Bowers, in his volume on commemoratives, called a lie, as Hoffecker elsewhere in his correspondence refers to local collectors buying a few of the coins.[8]

Legislation

R. Ewing Thomason of Texas introduced legislation for an Old Spanish Trail half dollar into the House of Representatives on March 4, 1935. The bill was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures.[9] That committee held a hearing, at which Thomason appeared, telling the members about Texas history and assuring them the bill would result in no expense to the government. On April 2, John J. Cochran of Missouri reported the bill back to the House on behalf of the committee, recommending it pass.[10] Cochran brought two commemorative coin bills, including the one for the Old Spanish Trail piece, to the House floor on April 3 as emergency measures, explaining to members dubious that the striking of half dollars could be urgent that they were needed for a celebration that summer, and that the bill had been delayed due to the committee chairman's illness. Marion A. Zioncheck of Washington state, who had been quizzing Cochran, asked "Is this for St. Louis again?"; Cochran responded, "No; this is not for St. Louis."[11] New York's Charles D. Millard asked if the minority (Republican) members of the committee had been consulted; Cochran assured him this was so and they were in favor of the bill. William D. McFarlane of Texas asked what the expense to the federal government would be; Cochran responded, "it will not cost the Government five cents".[12] The bill passed without recorded objection, after which Cochran got the Hudson, New York Sesquicentennial half dollar passed.[13]

In the Senate, the bill was referred to the Committee on Banking and Currency.[9] That bill issued a report on May 23 by Duncan U. Fletcher of Florida, recommending it pass without amendment.[14] When the bill was brought to the Senate floor on May 28, William Henry King of Utah asked if the bill had the Treasury Department's support, but Fletcher did not know as it was a House bill; his committee had approved it as similar bills had been passed for a number of expositions and other celebrations. The Majority Leader, Joseph Taylor Robinson of Arkansas, noted there would be no expense to the government; Fletcher agreed, stating it would make some money through seignorage. The bill passed without further debate,[15] and was enacted, authorizing 10,000 half dollars, with the signature of President Roosevelt on June 5, 1935.[9]

Preparation

Hoffecker provided sketches for the half dollar, and sent them to the Bureau of the Mint for approval. Mint Director Nellie Tayloe Ross on June 27 forwarded them to the Commission on Fine Arts for its recommendation, noting that the position of Hoffecker's initials between the anniversary dates was objectionable. The Commission sent the sketches to its sculptor member, Lee Lawrie, for his approval, and he thought they would make a good coin if modeled properly. The sketches had lacked the word "Liberty", something Ross had pointed out. Lawrie felt it must be included, and suggested it be inserted between the cow's horns, which it was. Lawrie also recommended the initials be made less conspicuous. The full commission approved the designs, subject to Lawrie's criticisms being addressed.[16]

Edmund J. Senn of El Paso was hired to make the required plaster models based on the designs and the requirements of the Fine Arts Commission.[17] Hoffecker related that he had sought to hire one of two or three sculptors in the East, but each would take too long and wanted liberty to make changes. Senn was unemployed, and, by Hoffecker's account, he stood over the sculptor, who worked in Hoffecker's garage.[18] The models were sent to the Fine Arts Commission, which did not like the appearance of the cow's head and required that it be modified. It also questioned the placing of the word LIBERTY on a riband, as if it were a motto, which it is not.[19] Senn revised his models, though little change was made to the head.[20]

Design

The obverse depicts the head of a cow, intended as a rebus for Cabeza de Vaca, of whom no portrait could be found. Instead, the literal translation of his title was used. There are no other design elements on the obverse, only lettering. Arlie Slabaugh in his volume on commemoratives found the obverse "unorthodox" but "it does what it was intended to do, tells the story and then stops, leaving a generally pleasing and uncluttered design".[2]

The reverse features a yucca in bloom, superimposed against a map of the five Gulf States, with a line intended to describe de Vaca's route, running from Florida to El Paso, which is the only place named,[2] Hoffecker, in submitting the design to the Mint, stated that he hoped there would be no objection to El Paso being named, as there was precedent for it.[21] but there are dots along the route representing St. Augustine, Jacksonville, Tallahassee, Mobile, New Orleans, Galveston and San Antonio. This is inaccurate, as de Vaca traveled along the Gulf Coast for the most part by boat rather than overland.[6] Hoffecker took further liberties, as the year 1535 was not a significant date in de Vaca's travels.[1]

Swiatek, in his 2012 volume on commemoratives, describes the Old Spanish Trail issue as "beautiful and very popular".[22] Bowers noted that it was "popular with collectors from the very start, and this enthusiasm has carried through to the present day".[23]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule, in his volume on U.S. commemorative coins and medals, said of the Old Spanish Trail piece that it "can safely be designated the ugliest commemorative coin ever produced by a United States mint. It may be the strongest contestant for the title of least attractive American coin ever manufactured under official auspices between 1793 and the present."[24] He ridiculed the cow's head, saying that using it to represent Cabeza de Vaca was akin to depicting a field of roses on the dime to represent Franklin Roosevelt.[25] Vermeule noted Slabaugh's praise that the obverse told a story and then stopped, and stated, "the question is whether or not the story is worth telling on a United States half-dollar."[25]

Production and distribution

There was a note in the June 1935 edition of The Numismatist (the ANA's journal) authored by Hoffecker, stating that he, as head of the Museum Committee, would be selling the Old Spanish Trail half dollars at $2 each, plus postage. He stated that only 10,000 would be issued, and "we wish all collectors to obtain a few and will not allow any speculator to hold up the public."[26] He placed an advertisement the following month, stating that he was ready to take orders and he hoped the coins would be available from the Mint in 60 days.[27]

The Philadelphia Mint in September struck 10,000 half dollars, plus eight extra that would be held for inspection and testing at the 1936 meeting of the annual Assay Commission.[17] Hoffecker later stated in a letter to another dealer that he paid for the coins, owned them, sold them, and the only two the El Paso Museum got were gifts from himself. Accordingly, the profits would have accrued to him. When testifying before Congress in March 1936, he denied having an ownership interest in them. Bowers, whose firm holds Hoffecker's papers, stated his belief that most of the coins were distributed by Hoffecker to collectors and other interested person, and that he avoided selling to speculators. He kept a quantity for himself, though he also denied that publicly. He wrote to another dealer in 1953 that he was still selling the half dollars, a few each month. When coins from Hoffecker's estate were sold in 1967, a group of 63 Old Spanish Trail half dollars was auctioned off.[29] Hoffecker kept the coin collecting community happy in the distribution of the issue; if there were dissenters, their complaints were not printed in The Numismatist. In 1936, Hoffecker was the distributor of the Elgin, Illinois, Centennial half dollar.[30] Anthony Swiatek and Walter Breen wrote in their volume on commemoratives that "no scandal attached itself to Hoffecker".[17]

The low mintage of the issue has made it desirable by those seeking to put together a type set of commemoratives, one of each design. The Old Spanish Trail half dollar sold at retail for about $4 in 1940, in uncirculated condition. It thereafter increased in value, selling for about $38 by 1955, and $510 by 1975.[31] The deluxe edition of R. S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins, published in 2018, lists the coin for between $1,050 and $1,450, depending on condition.[32] An exceptional specimen sold at auction for $25,300 in 2005.[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 Flynn, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 Slabaugh, p. 106.

- ↑ Slabaugh, p. 107.

- ↑ Slabaugh, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Flynn, p. 353.

- 1 2 Swiatek, p. 255.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 301–02.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 306.

- 1 2 3 "Old Spanish Trail Commemorative 50-Cent Pieces". ProQuest Congressional. Retrieved September 19, 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Coinage of 50-Cent Pieces in Commemoration of the Cabeza de Vaca Expedition and Opening of the Old Spanish Trail". United States House of Representatives. April 2, 1935.

- ↑ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 4951 (April 3, 1935)

- ↑ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 4951 (April 3, 1935)

- ↑ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 4952 (April 3, 1935)

- ↑ "Coinage of 50-Cent Pieces in Commemoration of the Cabeza de Vaca Expedition and Opening of the Old Spanish Trail". United States Senate. May 23, 1935.

- ↑ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 8318 (May 28, 1935)

- ↑ Taxay, pp. 175–76.

- 1 2 3 Swiatek & Breen, p. 180.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 304.

- ↑ Taxay, p. 176.

- ↑ Taxay, p. 178.

- ↑ Flynn, p. 171.

- ↑ Swiatek, p. 258.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 310.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 191.

- 1 2 Vermeule, p. 192.

- ↑ Hoffecker, L.W. (June 1935). "The Old Spanish Trail Half Dollar". The Numismatist: 375.

- ↑ Hoffecker, L.W. (June 1935). "Old Spanish Trail Half Dollars". The Numismatist: 479.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 301.

- ↑ Bowers, pp. 305–309.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 305.

- ↑ Bowers, pp. 310–11.

- ↑ Yeoman, p. 1080.

- ↑ Flynn, p. 173.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago, IL: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins 2014 (Mega Red 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.

External links