Maryland Tercentenary half dollar

| United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1934 |

| Mintage | 25,000 with 15 pieces for the Assay Commission |

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at the Philadelphia Mint without mint mark |

| Obverse | |

| |

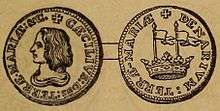

| Design | Bust of Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore |

| Designer | Hans Schuler |

| Design date | 1934 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Arms of Maryland |

| Designer | Hans Schuler |

| Design date | 1934 |

The Maryland Tercentenary half dollar depicts Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore on the obverse.[1]

Background

The Maryland Tercentenary Commission desired a commemorative half dollar honoring the 300th anniversary of the 1634 arrival of English settlers in what is now the state of Maryland. These early inhabitants had founded St. Mary's City on land granted by Charles I of England to Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore.[2][3] The Tercentenary Commission wanted to use profits from the coin to defray the expenses of the Tercentenary celebrations.[4]

In 1934, commemorative coins were not sold by the government—Congress, in authorizing legislation, usually designated an organization which had the exclusive right to purchase them at face value and vend them to the public at a premium.[5] In the case of the Maryland half dollar, the responsible group was the Tercentenary Commission, acting through its president or secretary.[6]

Legislation

Maryland's two senators, Millard E. Tydings and Phillips Lee Goldsborough, introduced a bill for a Maryland Tercentenary half dollar on March 6, 1934, and it was referred to the Committee on Banking and Currency.[7] That committee issued a report, through Senator Goldsborough, on March 13, recommending the bill pass without amendment.[8] The bill was brought to the House floor on March 20, and passed without any recorded discussion.[9]

The bill was transmitted to the House of Representatives and referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures. That committee made report on April 25, 1934, through New York Representative Andrew Somers, recommending the bill pass, but with several amendments, including increasing the authorized mintage from 10,000 to 25,000 and requiring that the federal government would not pay for the coinage dies and other preparations for the coinage.[10] Somers brought the bill to the House floor on May 2, and when he asked the House to consider it, Sam Rayburn of Texas stated that if there was to be debate, he would object. Somers stated that to his knowledge, there would be no debate. Thomas L. Blanton, also of Texas, proposed an amendment to increase the mintage further to 100,000, but this was merely pro forma, to be able to ask Somers questions. Somers stated that the figure of 25,000 had been arrived at in consultation with the Treasury Department. Blanton felt there was a need for more silver coins in circulation, but he and Somers agreed that commemorative coins, which rarely entered circulation and were generally picked out quickly, were not the answer. He withdrew his amendment, and the bill passed without further discussion.[11]

As the two houses of Congress had passed versions of the bill that were not identical, it returned to the Senate. On May 3, Goldsborough moved that the Senate accept the House's amendments, and the bill passed without debate.[12] It became the Act of May 9, 1934, authorizing 25,000 half dollars, with the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[6]

Preparation

Designs for the coin had already been prepared while the bill was pending, and on May 9, the date of passage, the commission's secretary, Hans Caemmerer, sent a telegram to the sculptor-member of the Commission of Fine Arts, Lee Lawrie, stating that the Treasury Department needed an immediate answer as to whether the designs were suitable. Lawrie journeyed by train to Philadelphia to visit the Mint there and confer with the Chief Engraver, John R. Sinnock. Lawrie had a number of suggestions, including deleting a dot between the words HALF and DOLLAR and respacing the letters in those words. The coin's designer, Hans Schuler of the Maryland Institute College of Art, made changes and brought the coin's plaster models back to the mint on the 14th; Sinnock generally approved of the changes but Lawrie had additional suggestions, including moving the words IN GOD WE TRUST from the reverse to the obverse, adjacent to Lord Baltimore, who had decreed religious freedom in Maryland. He also felt that Lord Baltimore's garments were not accurate, since he was portrayed with a broad collar Lawrie deemed more typical of Puritans rather than Cavaliers such as Baltimore, a Catholic.[13]

Schuler made the lettering changes, but would not accept the criticism of the collar, stating that he had based his depiction on a well-known painting of Baltimore by Gerard Soest. Lawrie did not argue further, and with the Tercentenary Commission anxious to have the coins struck as quickly as possible, the Commission of Fine Arts gave its approval. To save time, coinage dies for the issue were prepared by the Medallic Art Company of New York.[14]

Design

The obverse shows Lord Baltimore. Since the time of issue, a number of numismatic writers have criticized the manner in which he is depicted, especially his collar. Anthony Swiatek and Walter Breen, in their joint work on commemoratives, state that Schuler's reliance on the Soest painting "does not excuse the Puritan collar worn by Lord Baltimore, the Cavalier of Cavaliers. Schuler would have done better to go to Lord Baltimore's own coins, which show a very different portrait."[4] Don Taxay noted, "since Schuler's own coinage depicts him in a loosely draped garment, the [Fine Art] Commission's objection to the puritan collar was probably well founded."[15]

The reverse side features the Coat of Arms of Maryland;[16] the arms of Lord Baltimore quartered with those of his wife.[17][18] The Maryland piece and the York County, Maine Tercentenary half dollar (1936) are the only U.S. coins to have a cross as part of the design. The state motto, FATTI MASCHII PAROLE MEMINE, sometimes translated from Italian as "deeds are manly, words womanly" appears.[19] Swiatek and Breen noted in 1988 that the state "has not shown any disposition to repudiate this sexist rubbish".[17] The Maryland General Assembly in 2017 passed an act disavowing that translation, and stating that it meant "strong deeds, gentle words".[20] The sculptor's initials, HS, are found next to the M in MARYLAND, on the reverse.[16]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule, in his volume on U.S. commemorative coins and medals, complained that the Maryland piece "looks more like an advertising medal than a commemorative half-dollar".[21] He deemed the obverse conventional "save for the facing bust, which has been so often taken for good design by mediocre medalists".[22]. The reverse, which Vermeule called "standard fare" on numismatic items, "could almost be a policeman's badge".[23]

Production and distribution

In July 1934, the Philadelphia Mint struck 25,000 Maryland half dollars, plus 15 extra that would be held for inspection and testing at the 1935 meeting of the annual Assay Commission. They were delivered to the Tercentenary Commission on July 10, and were put on sale at $1 each.[24] This made the Maryland coin the first authorized under the Roosevelt administration to be issued. The Texas Centennial half dollar had been authorized by Congress in 1933, but would not be struck until October 1934.[19] By the end of 1934, about 15,000 Maryland half dollars had been sold.[25] By this time, the tercentenary celebrations had ended, and the commission lowered the price to $.75.[24] The price was lowered even more, to $.65, and the commission exhausted its stock. When Texas coin dealer L.W. Hoffecker enquired in May 1935, the commission advised him it was sold out, and that about 8,000 had been sold in bulk to dealers. Hoffecker testified before Congress in March 1936 about commemorative coin abuses, and stated that he had learned that about 1,000 had gone to a dealer in the Southwest, and when he visited the Tercentenary Commission's offices, the elevator operator told him that he had bought 500 to lay aside for the future.[25]

The Maryland Tercentenary half dollar sold at retail for about $1.50 in 1935, but had fallen back to about $1.25 in uncirculated condition in 1940. It thereafter increased in value, selling for about $10 by 1955, and $300 by 1985.[26] The deluxe edition of R. S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins, published in 2018, lists the coin for between $130 and $325, depending on condition. Between two and four pieces are known in proof condition,[27] including two that had been belonged to Chief Engraver Sinnock.[28] One such specimen sold at auction for $109,250 in 2012.[27]

References

- ↑ "American Numismatic Association". Money.org. 2015-11-02. Retrieved 2016-12-22.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 261.

- ↑ Swiatek, pp. 217–18.

- 1 2 Swiatek & Breen, p. 153.

- ↑ Slabaugh, pp. 3–5.

- 1 2 Flynn, pp. 351–52.

- ↑ "Province of Maryland 300th Anniversary Commemorative 50-Cent Peices [sic]". ProQuest Congressional. Retrieved September 19, 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Coins in Commemoration of Founding of Province of Maryland". United States Senate. March 13, 1934.

- ↑ 1934 Congressional Record, Vol. 80, Page 4890 (March 20, 1934)

- ↑ "Coins in Commemoration of Founding of Province of Maryland". United States House of Representatives. April 25, 1934.

- ↑ 1934 Congressional Record, Vol. 80, Page 7916 (May 2, 1934)

- ↑ 1934 Congressional Record, Vol. 80, Page 7992 (May 3, 1934)

- ↑ Taxay, pp. 137–40.

- ↑ Taxay, pp. 140–41.

- ↑ Taxay, p. 141.

- 1 2 Slabaugh, p. 87.

- 1 2 Swiatek & Breen, p. 151.

- ↑ Flynn, p. 121.

- 1 2 Swiatek, p. 218.

- ↑ "Chapter 496" (PDF). State of Maryland. May 4, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 184.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 186.

- ↑ Vermeule, pp. 184, 186.

- 1 2 Flynn, p. 122.

- 1 2 Bowers, p. 262.

- ↑ Bowers, pp. 263–64.

- 1 2 Yeoman, p. 1071.

- ↑ Swiatek & Breen, p. 164.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago, IL: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins 2014 (Mega Red 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.

External links