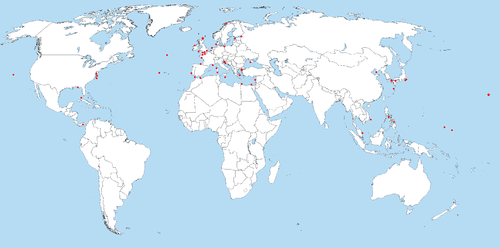

List of sunken battleships

Sunken battleships are the wrecks of large capital ships built from the 1880s to the mid 20th century that were either destroyed in battle, mined, deliberately destroyed in a weapons test, or scuttled. The battleship, as the might of a nation personified in a warship, played a vital role in the prestige, diplomacy, and military strategies of 20th century nations. The importance placed on battleships also meant massive arms races between the great powers of the 20th century such as the United Kingdom, the German Empire, Japan, the United States, France, Italy, Nazi Germany, Russia, and Spain.

Although the term "battleship" appears to have been coined in 1794,[1] the term first began to see wide usage to describe certain types of ironclad warships in the 1880s,[2] now referred to as pre-dreadnoughts. The commissioning and putting to sea of HMS Dreadnought, in part inspired by the results of the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905,[3] marked the dawn of a new era in naval warfare and defining an entire generation of warships: the battleships. This first generation, known as the "Dreadnoughts" (and later Super dreadnoughts), came to be built in rapid succession in Europe, the Americas, and Japan with ever more tension growing between the major naval powers. However, despite the enormous sums of money and resources dedicated to the construction and maintenance of the increasing number of battleships in the world, they typically saw little combat. With the exception of the naval battles of the Russo-Japanese War and Jutland, which would be one of the last large-scale battles between capital ships,[4] no decisive naval battles between battleships were fought. Although only one battleship, SMS Pommern, sank at Jutland, the faith placed in decisive naval battles evaporated in Germany in favor of continued warfare by attrition via submarines. When the First World War ended in 1918, much of the German High Seas Fleet was escorted to Scapa Flow, where almost all of the fleet under Ludwig von Reuter was scuttled to prevent its capture by the British. This was a fate shared by numerous other battleships.

Between the wars, the Washington Naval Treaty and the subsequent London Naval Treaty limited the tonnage and firepower of capital ships permitted to the navies of the world. The United Kingdom and the United States scrapped many of their aging dreadnoughts, while the Japanese began converting cruisers into fast battleships in the 1930s. In 1936, Italy and Japan refused to sign the Second London Naval Treaty and withdrew from the earlier treaties, prompting the United States and the United Kingdom to invoke an escalator clause in the treaty that allowed them to increase the displacement and armament of planned ships. The naval combat of World War Two saw many battleships belonging to the various nations destroyed as air power began to be realized as being crucial to naval warfare, rather than massive capital ships. As the battleship began to fall out of favor, some captured capital ships were decommissioned, stripped, and deliberately sunk in nuclear weapons tests.

The greatest loss of life in the sinking of a battleship was the 3,055 deaths aboard Yamato near Okinawa in 1945.[5]

Losses

Much like with battlecruisers, battleships typically sank with large loss of life if and when they were destroyed in battle. The first battleship to be sunk by gunfire alone,[6] the Russian battleship Oslyabya, sank with half of her crew at the Battle of Tsushima when the ship was pummeled by a seemingly endless stream of Japanese shells striking the ship repeatedly, killing crew with direct hits to several guns, the conning tower, and the water line or below it, which became the cause of the ship's sinking.[7][8] Battleships also proved to be very vulnerable to mines, as was evidenced in the Russo-Japanese War and both World Wars. After the Battle of Port Arthur,[9] a number of Russian and Japanese vessels were struck by mines and either sank or were scuttled to prevent their capture. A decade later, the Marine Nationale and Royal Navy lost three battleships, HMS Irresistible, HMS Ocean, and Bouvet, to Turkish mines in the waters of the Dardanelles. Torpedoes also proved to be very capable at sinking the mighty battleship: on November 21, 1944, USS Sealion sank Kongō with over 1200 casualties.[10] HMS Barham, another of the only two British battleships sunk by a submarine during the Second World War,[lower-alpha 1] was struck by three torpedoes fired from German submarine U-331.[lower-alpha 2] Barham could not make an attempt to dodge the incoming torpedoes and sank with 862 fatalities as a result of several magazine explosions that occurred after she had initially been hit by U-331's torpedoes.[13]

Although mines and torpedoes constantly threatened the battleship's dominance, it was the refinement of aerial technology and tactics that led to the replacement of the battleship with the aircraft carrier as the most important naval vessel. Initially, the large scale use of aircraft in naval combat was underrated and the idea that they could destroy battleships was dismissed. Still, the United States and the Japanese Empire experimented with offensive roles for aircraft carriers in their fleets.[14] One notable early military science pioneer of aviation in naval role was US Army General Billy Mitchell, who commandeered SMS Ostfriesland for testing of his theory in July 1921. Though these tests did not impress his contemporaries, they forced the US Navy to begin diverting some of its budget towards researching the matter further.[15] The belief that the aircraft carrier was junior to the battleship began to evaporate when the Imperial Japanese Navy, in a surprise attack, destroyed nearly the entire United States Pacific Fleet at anchor at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 solely by air power.[16] The captain of the Bismarck, Ernst Lindemann, had almost dodged the Royal Navy until he was undone by British reconnaissance aircraft. Although almost every sea battle in World War Two involved gunfire between surface warships to some degree,[17] their time as the senior ship of a nation's fleet had run its course.

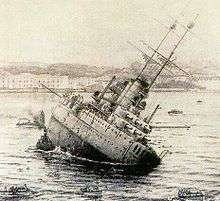

Those battleships belonging to the Central Powers that survived World War I often did not survive its aftermath. The most infamous example of the scuttling of capital ships after the First World War was the incident at Scapa Flow, where German admiral Ludwig von Reuter successfully scuttled 52 of the 74 ships of the High Seas Fleet.[18] The Austrians too disliked the idea of surrendering their fleet to their enemies, the Italians. On 1 November 1918, as the ship was being transferred to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, Austrian battleship Viribus Unitis was mined and sunk at Pola by two Italian frogmen, Raffaele Paolucci and Raffaele Rossetti, unaware of the transfer.[19] Similarly, on 27 November 1942, the Vichy French government scuttled the majority of the French fleet at Toulon. Scuttling a battleship was, repeatedly through history, a last act of defiance against an enemy.

By tradition and maritime law, sunken warships remain the property of the government of the nation that owned them, and many are treated as war graves.

Sunk in combat

The following ships were destroyed in battle and most are considered war graves.

| Name | Navy | Casualties | Date sunk | Location | Condition | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poltava[lower-alpha 3] | None | 5 December 1904[20] | Port Arthur[20] | Scrapped[24] | — |

| |

| Pobeda[lower-alpha 4] | None | 7 December 1904[27] | Port Arthur[20] | Scrapped[27] | Though 1922–23 is the most likely date of Pobeda's scrapping, there is some discussion over whether or not she served in the Japanese Imperial Navy as Suwo until being broken up in 1946.[27][28] This is unlikely because this does not appear in the Fukui's Shinzo's authoritative work, Japanese Naval Vessels at the End of World War II. | .jpg) | |

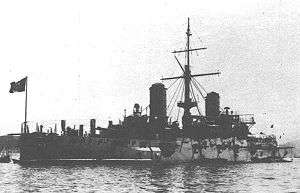

| Oslyabya | 470–514 killed[lower-alpha 5] | 27 May 1905[6] | Tsushima Strait[30] | Unknown | First all-steel capital ship to be sunk by gunfire alone.[6] |  | |

| Imperator Aleksandr III | Lost with all hands[31] | 27 May 1905[32] | Tsushima Strait[33] | Unknown | A granite obelisk stands in St. Petersburg in memory of the crew of Imperator Aleksandr III.[34] | ||

| Borodino | 854 killed, 1 captured[33] | 27 May 1905[35] | Tsushima Strait[32] | Unknown | — |

| |

| Knyaz Suvorov | 908 killed, 20 captured[31] | 27 May 1905[36] | Tsushima Strait[32] | Unknown | — |

| |

| Navarin | 741 killed, 1 captured[37][38] | 28 May 1905[39] | Tsushima Strait[38] | Unknown | — |

| |

| Sissoi Veliky | 47 killed, 613 captured[40] | 28 May 1905[41] | Tsushima Strait[32] | Unknown | — |

| |

| HMS Formidable | 547 killed[42] | 1 January 1915[42] | 50°13′N 3°4′W / 50.217°N 3.067°W Off Portland Bill, English Channel[42] | Unknown | — |

| |

| HMS Irresistible | 150 killed[43] | 18 March 1915[44] | Dardanelles[14] | Unknown | A flag from HMS Irresistible, recovered from the ship by Ottoman forces, now adorns a wall at the Istanbul Military Museum. |  | |

| HMS Goliath | 570 killed[45] | 13 May 1915[45] | Dardanelles[45] | Unknown | — |

| |

| HMS Triumph[lower-alpha 6] | 78 killed[47] | 25 May 1915[47] | Near Gaba Tepe, Gallipoli Peninsula[47] | Unknown | — |

_as_completed_January_1904.jpg) | |

| HMS Majestic | 40–49 killed[lower-alpha 7] | 27 May 1915[49] | 40°02′30″N 26°11′02″E / 40.04167°N 26.18389°E Cape Helles, Gallipoli Peninsula[49] | Unknown | — |

| |

| SMS Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm[lower-alpha 8] | 258 killed[51] | 8 August 1915[52] | Dardanelles[53] | Unknown | — |

| |

| SMS Pommern | Lost with all hands[54] | 1 June 1916[54] | North Sea[55] | Unknown | Only battleship to sink at the Battle of Jutland on either side.[55] | ||

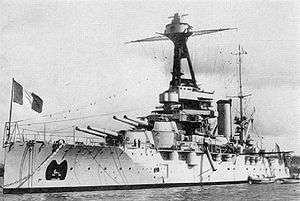

| Suffren | Lost with all hands[56] | 26 November 1916[56] | 39°10′N 10°48′W / 39.167°N 10.800°W Off Lisbon, Portugal[56] | Unknown | — |

| |

| Gaulois | Four killed[57] | 27 December 1916[58] | 36°15′N 23°42′E / 36.250°N 23.700°E Off Cape Maleas, Aegean Sea[57] | Unknown | — |

| |

| HMS Cornwallis | 15 killed[59] | 9 January 1917[60] | 35°06′N 15°11′E / 35.100°N 15.183°E Off Malta[60][61] | Unknown | — |

| |

| Danton | 296 killed[62] | 19 March 1917[62] | 38°45′35″N 8°3′30″E / 38.75972°N 8.05833°E Mediterranean Sea[62] | Upright under 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) of water.[62] | — |

| |

| SMS Viribus Unitis | 300 killed[63] | 1 November 1918[63] | 44°52′9″N 13°49′9″E / 44.86917°N 13.81917°E Pula, Croatia[63] | Unknown | SMS Viribus Unitis was blown up by Italian frogmen while it was being transferred to the newly formed Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs,[63] who had already named her Jugoslavija. |  | |

| SMS Szent István | 89 killed[64] | 10 June 1918[64] | 44°12′07″N 14°27′05″E / 44.20194°N 14.45139°E Premuda, Adriatic Sea | Capsized under 66 meters (217 ft) of water.[65] | — |

| |

| HMS Britannia | 50 killed, 80 injured[66] | 9 November 1918[67] | 35°43′N 5°53′W / 35.717°N 5.883°W Off Cape Trafalgar, Strait of Gibraltar[67] | Unknown | — |

_sinking_on_9_November_1918.jpg) | |

| HMS Royal Oak | 833 killed[68] | 14 October 1939[69] | 58°55′N 2°59′W / 58.917°N 2.983°W Scapa Flow[70] | Capsized under 33 meters (108 ft) of water.[71] Royal Oak sank with about 3,000 gallons of fuel, which became such an ecological concern that the Ministry made plans to remove the oil or even raise the ship and salvage it.[72] However, after years of work by Briggs Marine, some 16,000 gallons of fuel were removed from the wreck, and the Ministry of Defence declared it to be no longer actively leaking fuel.[73] It remains to be seen how the thousands of pounds of live munitions on board Royal Oak[74] will be addressed. | The ship's bell is the centerpiece to a memorial to those who died aboard Royal Oak at St Magnus' Cathedral in Kirkwall. | .jpg) | |

| Bretagne | 977 killed[75] | 3 July 1940[76] | Mers-el-Kébir, Algeria[76] | Scrapped[77] | — |

| |

| Kilkis[lower-alpha 9] | None | 23 April 1941[79] | Salamis Naval Base, near Salamis[79] | Scrapped[80] | — |

| |

| Lemnos[lower-alpha 10] | None | 23 April 1941[79] | Salamis Naval Base, near Salamis[79] | Scrapped[82] | — |

| |

| Bismarck | 2086 killed, 114 captured.[83] | 27 May 1941[84] | 48°10′N 16°12′W / 48.167°N 16.200°W 650 kilometers (400 mi) from Brest, North Atlantic[85] | Upright and in good condition under 4,791 meters (15,719 ft) of water.[85] | — |

| |

| Petropavlovsk[lower-alpha 11] | 326 killed[88] | 23 September 1941[88] | Leningrad[88] | Scrapped[87] | Although the Marat was sunk by two German bombs, the credit for her sinking is often given purely to Stuka pilot Oberleutnant Hans-Ulrich Rudel.[88] |  | |

| HMS Barham | 862 killed[89][90] | 25 November 1941[91] | 32°34′N 26°24′E / 32.567°N 26.400°E Off Egypt[89] | Unknown | — |

| |

| USS Arizona | 1177 killed[92] | 7 December 1941[93] | 21°21′53″N 157°57′0″W / 21.36472°N 157.95000°W Pearl Harbor[92] | Heavily damaged as a result of the attack on Pearl Harbor. After being struck off the Naval Vessel Register on 1 December 1942, Arizona was deemed to be in such terrible condition that, unlike most of the other ships around her, she could not be made serviceable again even after salvaging.[94] Arizona's surviving superstructure was removed and scrapped in 1942, and her main armament followed in the next year and a half.[95] Today, USS Arizona is part of a larger memorial dedicated to the lives lost on 7 December 1941.[96] | The amidships section had served as a ceremonial platform on the wreck but was cut away to make room for today's overlying memorial. One of the ship's bells is at the University of Arizona,[97] an anchor and a restored gun barrel is located at the Wesley Bolin Memorial Plaza, and several of her guns were later used aboard USS Nevada.[98] Other artifacts from the ship, such as items from the ship's silver service, are on permanent exhibit in the Arizona State Capitol Museum.[99] | .jpg) | |

| USS Utah | 64 killed[100] | 7 December 1941[100] | 21°22′7″N 157°57′44″W / 21.36861°N 157.96222°W Pearl Harbor | Utah capsized during the attack, and was partially salvaged but not recovered. She was later partially righted and pulled closer to shore and away from the channel.[101] Utah' wreck is almost completely submerged, with a small amount of highly corroded superstructure visible above the surface.[100] | In 1972, a memorial consisting of a 70 ft (21 m) walkway from nearby Ford Island that terminates in a platform with a flagpole and a plaque.[102] Other relics of the Utah are preserved at the Utah State Capitol and are regularly on display.[103] |  | |

| HMS Prince of Wales | 327 killed[104] | 10 December 1941[105] | 3°33′36″N 104°28′42″E / 3.56000°N 104.47833°E South China Sea[106] | Capsized under 71 meters (233 ft) of water. Reported to have been heavily salvaged.[106] | The ship's bell was recovered, restored, and displayed in the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool.[106] |  | |

| Asahi | 16 killed[107] | 25 May 1942[108] | 10°N 110°E / 10°N 110°E 100 miles (160 km) from Cape Paderan, Vietnam[108] | Unknown | — |

_(14775946872).jpg) | |

| Roma | 1393 killed[109] | 9 September 1943[110] | 41°9′28″N 8°17′35″E / 41.15778°N 8.29306°E 30 kilometers (19 mi) north of Sardinia | Capsized, blown in half underneath 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) of water.[111] | — |

_starboard_quarter_view.jpg) | |

| Hiei | 188 killed[112] | 14 November 1942[112] | 9°N 159°E / 9°N 159°E Off Guadalcanal[113] | Unknown | — |

| |

| Kirishima | 212 killed[114] | 15 November 1942[114] | Off Guadalcanal[113] | Located in 1992 by Robert Ballard, Kirishima lies upside down in 1,100 meters (3,600 ft) of water.[115] | — |

| |

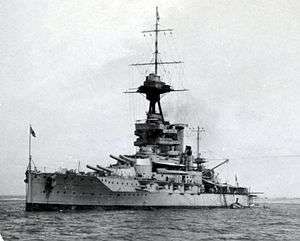

| Scharnhorst | 1932 killed, 36 captured[116] | 26 December 1943[117] | 72°16′N 28°41′E / 72.267°N 28.683°E near the Norwegian North Cape[118] | Scharnhorst, heavily damaged by the action of Battle of the North Cape, lies upside down in 290 meters (950 ft) of water.[119] | — |

| |

| Strasbourg | None | 18 August 1944[120] | Bay of Lazaret[120] | Scrapped[120] | Strasbourg was originally scuttled in Toulon harbor during the scuttling of the French fleet there in 1942, but she was raised in 1943, towed to the Bay of Lazaret, and then sunk by American aircraft 18 August 1944.[120] |  | |

| Jean Bart[lower-alpha 12] | None | 28 August 1944[122] | Toulon, France[122] | Scrapped[123] | — |

| |

| Musashi | 1023 killed[124] | 24 October 1944[125] | 13°7′N 122°32′E / 13.117°N 122.533°E Sibuyan Sea[126] | Heavily damaged by the action of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Located under 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) of water in several pieces.[127][128] | — |

| |

| Fusō | 1620 killed[129] | 25 October 1944{[129] | Surigao Strait[129] | Heavily damaged by the action of the Battle of Surigao Strait. | — |

| |

| Yamashiro | 1626 killed[130] | 25 October 1944[131] | Surigao Strait[131] | Unknown. | Diver John Bennett had claimed to have discovered the wreck of the Yamashiro, but no confirmation has since been forthcoming as of 2013.[132] |  | |

| Tirpitz | 950–1204 killed[lower-alpha 13] | 12 November 1944[118] | 69°38′50″N 18°48′30″E / 69.64722°N 18.80833°E Håkøybotn Bay, Norway[139] | Somewhat salvaged after the Second World War.[135] | Gordon Williamson states that fragments of the Tirpitz's armor are still being sold by a Norwegian company.[136] | .jpg) | |

| Kongō | 1250 killed[114] | 21 November 1944[140] | 26°9′N 121°23′E / 26.150°N 121.383°E Taiwan Strait[140] | Unknown | Kongō was originally built in England as a battlecruiser,[141] but she was extensively modified into a fast battleship in 1935.[142] She was the only Japanese battleship to be sunk by a submarine as well as the last battleship to be sunk by a submarine.[114] | ||

| Conte di Cavour | None | 23 February 1945[143] | Taranto Harbor[144] | Scrapped[145] | — |

| |

| Yamato | 3055[5] | 7 April 1945[146] | 30°22′N 128°4′E / 30.367°N 128.067°E East China Sea[147] | Broken in half at a depth of 340 meters (1,120 ft) of water. Bow section is upright, while the main section of Yamato is upside down.[147] | A nine-minute video of the 2015 survey that identified the ship is shown at the Yamato Museum at Kure,[148][149] itself founded a decade prior in 2005 near the shipyards that built Yamato.[150] The museum also features a titanic 26.3-meter (86 ft) long, 1:10 scale model of the Yamato as its centerpiece.[151] |  | |

| Haruna | 65 killed[114] | 24 July 1945[114] | Kure, Japan[114] | Scrapped[114] | — |

%2C_on_8_October_1945_(80-G-351726).jpg) | |

| Settsu | None | 29 July 1945[152] | Kure, Japan[152] | Scrapped[152] | Settsu had already foundered while attempting to flee from Kure, but American aircraft forced the crew to abandon the ship.[152] |  | |

| Ise | 50 killed[153] | 28 July 1945[153] | Kure, Japan[153] | Scrapped[153] | — |

| |

| Hyūga | 200+ killed[154] | 1 August 1945[154] | 34°10′N 132°33′E / 34.167°N 132.550°E Kure, Japan[154] | Scrapped[154] | — |

|

Converted battleships

Two battleships were converted into aircraft carriers either during construction or after entering service; both ships were sunk by combat action during World War II.

| Name | Navy | Casualties | Date sunk | Location | Condition | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Eagle | 131 killed[155] | 11 August 1942[155] | 38°3′0″N 3°1′12″E / 38.05000°N 3.02000°E near Majorca[155] | Unknown |  | |

| Shinano | 1435 killed[156] | 29 November 1944[156] | 32°7′N 137°4′E / 32.117°N 137.067°E 105 kilometers (65 mi) south of mainland Japan under 4,000 meters (13,000 ft) of water.[156] | Unknown |  | |

Lost at sea

The following battleships were lost at sea for reasons other than combat, such as foundering or being mined.

| Name | Navy | Casualties | Date sunk | Location | Condition | Fate | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Victoria | 358 killed[157] | 22 June 1893[157] | Near Tripoli, Lebanon[157] | According to the dive team that discovered Victoria, the ship lies vertically upright under 140 meters (460 ft) of water. Due to Victoria's weight and propulsion, she became deeply embedded in the soft sea floor. Only about 70 meters (230 ft) of the ship is visible above the sea floor today.[157] | Accidentally rammed and sunk by HMS Camperdown[157] |  | |

| Petropavlovsk | 679 killed[158] | 13 April 1904[159] | Yellow Sea[160] | Unknown | Struck a mine[160] |  | |

| Hatsuse | 496 killed[161] | 15 May 1904[162] | 38°37′N 121°20′E / 38.617°N 121.333°E Yellow Sea[163] | Unknown | Struck a mine[162] |  | |

| Yashima | None | 15 May 1904[164] | 38°34′N 121°40′E / 38.567°N 121.667°E Yellow Sea[165] | Unknown | Struck two mines[165] |  | |

| HMS Montagu | None | 30 May 1906[166] | Lundy Island, England[166] | Almost entirely salvaged.[167] | Foundered on Lundy Island[166] | _Aground_Lundy_Island_1906.jpg) | |

| Liberté | 250 killed[168] | 25 September 1911[168] | Toulon, France[169] | Scrapped[169] | Destroyed by internal explosion[170] |  | |

| HMS Audacious | One killed[171] | 27 October 1914[171] | 55°32′16″N 7°24′33″W / 55.53778°N 7.40917°W 39 kilometers (24 mi) of Tory Island[172][173] | Capsized under 64 meters (210 ft) of water.[174][172] | Struck a mine[175] |  | |

| HMS Bulwark | 736 killed[176] | 26 November 1914[176] | 51°25′N 0°39′E / 51.417°N 0.650°E Off Sheerness, England[176] | Unknown | Destroyed by internal explosion[176] |  | |

| HMS Ocean | Unknown | 18 March 1915[177] | Dardanelles[177] | Unknown | Struck a mine[177] | .jpg) | |

| Bouvet | 639 killed[58] | 18 March 1915[178] | 40°01′15″N 26°16′30″E / 40.02083°N 26.27500°E Dardanelles[178] | Unknown | Struck a mine[179] |  | |

| Benedetto Brin | 454 killed[180] | 27 September 1915[180] | Brindisi, Italy[180] | Unknown | Destroyed by internal explosion[181] |  | |

| HMS King Edward VII | None | 6 January 1916[182] | Off Cape Wrath, Scotland.[182] | Capsized under 108 meters (354 ft) of water.[183] | Struck a mine[182] | _sinking_on_6_January_1916.jpg) | |

| HMS Russell | 125 killed[184] | 27 April 1916[185] | 35°54′N 14°36′E / 35.900°N 14.600°E Off Valletta, Malta[184][185] | Capsized under 110 meters (360 ft) of water.[184][185] | Struck a mine[184][185] |  | |

| Leonardo da Vinci | 448 killed[186] | 2 August 1916[187] | Taranto, Italy[188] | Scrapped[187][189] | Destroyed by internal explosion[186] |  | |

| Imperatritsa Mariya | 228 killed[190] | 20 October 1916[191] | Sevastopol, Ukraine[191] | Scrapped[192] | Destroyed by internal explosion[190] |  | |

| Regina Margherita | 675 killed[193] | 12 December 1916[194] | Off Valona, Albania[194] | Capsized, laying on her starboard side at a depth of 68 meters (223 ft).[195] | Struck two mines[195] |  | |

| Peresvet[lower-alpha 14] | 116–167 killed[lower-alpha 15] | 4 January 1917[198] | Off Port Said, Egypt[198] | Unknown | Struck a mine[198] |  | |

| HMS Vanguard | 843 killed[200] | 9 July 1917[201] | 58°51′24″N 3°6′22″W / 58.85667°N 3.10611°W Scapa Flow[201] | Unknown, rests under 14.2 meters (47 ft) of water.[201] | Destroyed by internal explosion[201] |  | |

| Kawachi | 600–700 killed[lower-alpha 16] | 2 July 1918[204] | 34°0′N 131°36′E / 34.000°N 131.600°E | Partially salvaged.[206] | Destroyed by internal explosion[206] |  | |

| HMS Prince George[lower-alpha 17] | None | 30 December 1921[207] | 52°44′5″N 4°38′23″E / 52.73472°N 4.63972°E Off Camperduin, the Netherlands[207] | Upright and visible from shore, partially scrapped.[207] | Foundered off Camperduin, the Netherlands[207] |  | |

| France | Three killed[208] | 26 August 1922[208] | 47°27′6″N 3°2′0″W / 47.45167°N 3.03333°W Quiberon Bay, France[208] | Unknown | Foundered in Quiberon Bay[208] |  | |

| España | None | 26 August 1923[209] | Cape Tres Forcas, Morocco[209] | Somewhat salvaged, including a 305 mm (12.0 in) and a 102 mm (4.0 in) gun, but mostly destroyed by severe storms.[209] | Foundered[209] | .jpg) | |

| Alfonso XIII[lower-alpha 18] | Five killed[211] | 30 April 1937[211] | 43°31′26″N 3°40′44″W / 43.52389°N 3.67889°W Off Santander, Spain[211] | Unknown | Struck a mine[212] |  | |

| Jaime I | None | 17 June 1937[213] | Cartagena, Spain | Scrapped[214] | Destroyed by internal explosion[213] | .svg.png) | |

| SMS Schlesien | None | 3 May 1945[215] | Off Zinnowitz, Germany[215] | Scrapped[216][215] | Struck a mine[215] |  | |

| Mutsu | 1121 killed[217] | 8 June 1943[218] | 33°58′N 132°24′E / 33.967°N 132.400°E Seto Inland Sea[218] | Due to salvaging efforts that ceased in the 1990s,[218] the only major piece of the wreckage that remains is a 35-meter (115 ft) stretch of the hull from the bridge to turret No. 1 at a depth of about 12 meters (39 ft).[219] | Destroyed by internal explosion[218] |  | |

| USS Oklahoma | None | 17 May 1947[220] | Unknown, northeast of Hawaii[220] | Unknown | Sank in a storm[lower-alpha 19] |  | |

| São Paulo | None | November 1951[222][223] | Unknown | Unknown | Sank in a storm[lower-alpha 20] |  | |

| Giulio Cesare[lower-alpha 21] | 608 killed[227] | 29 October 1955 | 44°37′7″N 33°32′8″E / 44.61861°N 33.53556°E Sevastopol, Ukraine | Scrapped[228] | Destroyed by internal explosion[lower-alpha 22] |  |

Scuttled

The following battleships were intentionally sunk while not engaged in battle.

| Name | Navy | Casualties | Date sunk | Location | Condition | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dingyuan | None | 10 February 1895 | Weihaiwei | Unknown | - |

| |

| Sevastopol | 11 killed[231] | 2 January 1905[232] | Port Arthur[231] | Unknown | — |

| |

| HMS Hood | None | 4 November 1914[233] | 50°34′9″N 2°25′16″W / 50.56917°N 2.42111°W Portland Harbour[233] | Upside down, divable | — |

||

| Masséna | None | 9 November 1915[234] | Cape Helles, Gallipoli[234] | Unknown | — |

| |

| Slava | Three killed[235] | 17 October 1917[236] | Moon Sound, Estonia[236] | Scrapped[237] | — |

| |

| Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya[lower-alpha 23] | None | 18 June 1918[192] | 44°42′23″N 47°48′43″E / 44.70639°N 47.81194°E Novorossiysk, Russia[192] | Unknown | — |

| |

| SMS König | None | 21 June 1919[240] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[240] | Capsized under about 35 meters (115 ft) of water.[241] Somewhat damaged by metal scavenging.[242] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow[240] |  | |

| SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm | One killed[243] | 21 June 1919[243] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[243] | Capsized under about 45 meters (148 ft) of water.[244] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow. |  | |

| SMS Markgraf | Two killed[245] | 21 June 1919[245] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[245] | Capsized under about 45 meters (148 ft) of water.[246] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow. |  | |

| SMS Kaiser | None | 21 June 1919[247] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[247] | Scrapped[247] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow and then broken up starting 1930.[247] |  | |

| SMS Friedrich der Grosse | None | 21 June 1919[247] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[247] | Scrapped[247] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow and then broken up.[247] Friedrich der Grosse's bell was returned to the Federal Republic of Germany and today is on display at the German Navy sea base at Glücksburg.[247] |  | |

| SMS Kaiserin | None | 21 June 1919[247] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[247] | Scrapped[247] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow and then broken up.[247] |  | |

| SMS Prinzregent Luitpold | None | 21 June 1919[247] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[247] | Scrapped[247] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow and then broken up.[247] |  | |

| SMS König Albert | None | 21 June 1919[247] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[247] | Scrapped[247] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German Fleet in Scapa Flow and then broken up.[247] |  | |

| SMS Grosser Kurfürst | None | 21 June 1919[240] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[240] | Scrapped[240] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German Fleet in Scapa Flow and then broken up.[240] Her bell was purchased at auction by the National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth, Hampshire.[248] |  | |

| SMS Bayern | None | 21 June 1919[249] | Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow[249] | Scrapped[249] | Sunk in the scuttling of the German Fleet in Scapa Flow and then broken up. Her bell is on display at the Kiel Fördeklub.[249] |  | |

| Rostislav | None | November 1920[250] | 45°25′0″N 36°37′43″E / 45.41667°N 36.62861°E Strait of Kerch[250] | Partially salvaged, reported to be extant albeit sinking into silt.[251] | — |

| |

| Dunkerque | None | 27 November 1942[252] | Toulon, France[252] | Scrapped[252] | — |

||

| Provence | 27 November 1942[77] | Toulon, France[77] | Scrapped[77] | — |

| ||

| HMS Centurion | None | 9 June 1944[253] | Off Normandy[253] | Unknown | HMS Centurion's badge is on display at Shugborough Hall.[254] |  | |

| Courbet | None | 9 June 1944[255] | Off Sword Beach, Normandy[255] | Scrapped[255] | — |

| |

| SMS Schleswig-Holstein | None | 21 March 1945[256] | Marienburg (Malbork), Poland[257] | Reported to be submerged and in poor condition.[258] | Schleswig-Holstein's bell is on display Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr in Dresden as of 1990.[216] |  | |

| Gneisenau | None | 27 March 1945[259][260] | Gotenhafen (Gdynia), Poland[260] | Scrapped[261] | The damage that finally put Gneisenau out of action was a raid by the Royal Air Force on the night of 26–27 February 1942 that killed 112 men, and injured another 21.[262] She would finally be permanently sunk as a blockship in 1945 to impede Soviet forces advancing on the city of Gotenhafen.[260] One of her guns, dubbed "Caesar," was removed and placed at Austrått Fort, near Trondheim as the coastal gun "Orlandert."[260] It is today maintained as a museum.[263] |  | |

| SMS Zähringen | None | 26 March 1945[264] | Gotenhafen (Gdynia), Poland[264] | Scrapped[264] | — |

|

Expended as targets

The following battleships were intentionally sunk as targets. While cheaper disposable targets were conventionally used to maintain crew proficiencies, actual ships were sometimes used to test theories about armor, ammunition, or tactics in real circumstances.

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ There is a case for the number of British-built battleships sunk by submarines being three rather than two, as the Japanese warship Kongō was a British-built battlecruiser reconstructed as a fast battleship.

- ↑ U-331's captain, Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Diedrich von Tiesenhausen, believed that only one of his torpedoes struck Barham.[11] von Tiesenhausen was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross for this action.[12]

- ↑ Poltava was sunk by Japanese artillery 5 December 1904 during the Siege of Port Arthur,[20] then she was captured, refloated, given the Japanese name Tango, and refitted.[21][22][23] She was sold back to the Russian Empire during World War I and renamed Chesma.[22][24]

- ↑ Pobeda, like Poltava, was sunk by Japanese artillery at the Siege of Port Arthur on 7 December 1904,[25] but was refloated by the Japanese and given the name Suwo, and also refitted.[26]

- ↑ McLaughlin gives the death toll at 470 men,[29] while Campbell gives 514.[8] Neither Forczyk nor McLaughlin give numbers for the amount of sailors rescued,[6] but Campbell states that 385 men were saved by Russian destroyers.[8]

- ↑ Originally, Triumph was built for the Chilean Navy and christened Libertad, or Liberty.[46]

- ↑ R. A. Burt's British Battleships 1889–1904 states 49 men died in HMS Majestic's sinking,[48] while according to Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921, only 40 men were killed.[49]

- ↑ SMS Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm would be sold to the Ottoman Empire in 1910, and she was renamed Barbaros Hayreddin.[50]

- ↑ Prior to her service in the Hellenic Navy, Kilkis was the American battleship USS Mississippi.[78]

- ↑ Before being purchased by the Greek government and renamed, Lemnos was the American battleship USS Idaho.[81]

- ↑ Also known by the names Marat, after the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat,[86] and Volkhov.[87]

- ↑ In 1936, Jean Bart was renamed the Océan to free the name up for the Richelieu-class battleship of the same name, then under construction.[121]

- ↑ Ranges for casualties aboard the Tirpitz range wildly. William Garzke and Robert Dulin place the number of fatalities at "about 950,"[133] but Siegfried Breyer and Erich Gröner give a specific 1204 deaths.[134][135] The numbers in between are provided by Gordon Williamson, with a death toll of 971,[136] Niklas Zetterling and Michael Tamelander with an estimate of nearly 1000,[137] and John Sweetman with a figure of 1000 out of a crew of 1900.[138]

- ↑ The ship launched as Peresvet and was scuttled by the Russian Empire at the Siege of Port Arthur on 7 December 1904, but was raised and put to sea again by the Japanese and christened the Sagami.[196] The Japanese then sold the ship back to the Russians, who gave her the name Chesma.[197]

- ↑ Anthony Preston gives the death toll of the ship's second (and final) sinking at 167[198] while McLaughlin, in Russian & Soviet Battleships, gives a more modest 116 fatalities.[199]

- ↑ The number of casualties that resulted from the explosion of the Kawachi are high, they are disputed amongst the sources provided. Hans Lengerer's journal Battleships Kawachi and Settsu says that 600 men died,[202] and Sander Kingsepp tacks on an additional 18 fatalities.[203] Gardiner and Gray and Jentschura, Jung and Mickel, however, agree on a figure of 700 killed.[204][205]

- ↑ Sometime in mid-1918, Prince George was renamed Victoria II,[207] after her sister ship HMS Victorious,[49] but her name reverted to Prince George in February 1919.[49]

- ↑ The Alonso XIII was renamed the España,[210] the name of her sister ship, which had foundered in 1923,[209] after the unpopular king of Spain had been exiled.[210]

- ↑ USS Oklahoma has been sunk twice. She was first sunk during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.[221] After the war, she was refloated and was tugged in May 1947 but sank in a storm on 17 May more than 500 miles (800 km) from Hawaii, nearly taking the two tugboats with her to the ocean floor.[220]

- ↑ Sources are disputed as to the date of the sinking. M. J. Whitley and several Brazilian gives the date at 6 November,[222][224] but contemporary newspapers use 4 November.[223][225]

- ↑ After World War Two, the Giulio Cesare was given to the Soviet Union and was given the name Novorossiysk.[226][227]

- ↑ The destruction of the Novorossiysk is surrounded in controversy. The official explanation for the explosion that sank her was that a German mine left over from the Second World War blew up while she was in port (which was substantiated by the presence of such mines within 50 m (160 ft)), but theories abounded that Italian frogmen were responsible.[228][229][230]

- ↑ Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya was laid down as Ekaterina II, but this was only a formality.[238] Later, she was renamed Svobodnaya Rossiya (Russian: Free Russia) by February Revolutionists.[239]

- ↑ USS Texas was renamed the San Marcos 15 February 1911 to free the name for USS Texas.[265]

- ↑ On 6 June 1905, the Imperator Nikolai I was renamed Iki.[270]

- ↑ On 30 April 1919, the Iowa was renamed Coast Battleship No. 4 to free her name for one of the six new South Dakota-class battleships,[278] which would be abandoned.

- ↑ After being raised and put into Japanese service, the Retvizan was renamed the Hizen.[282]

- ↑ After being captured by the Japanese, the Oryol was given the name Iwami.[284]

Citations

- ↑ "Battleship", The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 4 April 2000.

- ↑ Stoll, J. Steaming in the Dark?, Journal of Conflict Resolution Vol. 36 No. 2, June 1992.

- ↑ Breyer 1973, p. 115.

- ↑ Jeremy Black, "Jutland's Place in History," Naval History (June 2016) 30#3 pp. 16–21.

- 1 2 "Combined Fleet – tabular history of Yamato". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Forczyk 2009, p. 62.

- ↑ Forczyk 2009, pp. 61–62.

- 1 2 3 Campbell 1978, pp. 128–31.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 239.

- ↑ Stille 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ Jones 1979, pp. 225–32.

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Kapitänleutnant Freiherr Hans-Diedrich von Tiesenhausen". uboat.net. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ↑ Jones 1979, pp. 258–59.

- 1 2 Grant 2008, p. 273

- ↑ Reid, John Alden. "Bomb the Dread Noughts!" Air Classics, 2006.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 274.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 273: "In the event, World War II did involve a good number of battles in which exchange of gunfire between of gunfire between large surface warships was crucial, or even the sole action, and in most engagements it played at least a part."

- ↑ Herwig 1980, p. 256.

- ↑ Franco Favre, La Marina nella Grande Guerra. Le operazioni navali, aeree, subacquee e terrestri in Adriatico, pp. 262–64.

- 1 2 3 4 McLaughlin 2003, p. 164.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 451.

- 1 2 Lengerer (September 2008), p. 52.

- ↑ Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, p. 19.

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2003, p. 91.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, pp. 115, 163–64.

- ↑ Lengerer 2008, pp. 41, 43–44.

- 1 2 3 Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, p. 20.

- ↑ McLaughlin (September 2008), p. 49.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 61.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 251.

- 1 2 Forczyk 2009, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Grant 2008, p. 250.

- 1 2 Campbell 1978, p. 135.

- ↑ "Cathedrals and churches of Saint Petersburg – St.Nicholas Cathedral". Paltra Travel. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Forczyk 2009, pp. 67, 70.

- ↑ Campbell 1978, p. 187.

- ↑ Forczyk 2009, p. 70.

- 1 2 Warner & Warner 2002, p. 514.

- ↑ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 122.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 83.

- ↑ Bogdanov 2004, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 Burt 1988, pp. 170–72.

- ↑ Burt 1988, p. 174.

- ↑ Chesneau 1979, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Burt 1988, pp. 158–59.

- ↑ Burt 1988, p. 262.

- 1 2 3 Burt 1988, p. 276.

- ↑ Burt 1988, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 7.

- ↑ Langensiepen & Güleryüz 1995, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Langensiepen & Güleryüz 1995, p. 28.

- ↑ Hore 2006, p. 66.

- ↑ Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 390.

- 1 2 Staff 2010, p. 13.

- 1 2 Campbell 1998, p. 338.

- 1 2 3 Caresse 2010, p. 26.

- 1 2 Caresse 2012, pp. 133–34.

- 1 2 Grant 2008, p. 263.

- ↑ Burt 1988, p. 209.

- 1 2 Burt 1988, p. 214.

- ↑ Chesneau 1979, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 Amos, Jonathan (19 February 2009). "Danton wreck found in deep water". BBC News. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Slučaj bojnog broda 'Viribus Unitis'" (in Croatian).

- 1 2 Sieche 1991, pp. 127, 131.

- ↑ Sieche 1991, pp. 138, 142.

- ↑ Burt 1988, p. 253.

- 1 2 "HMS Britannia Sunk". The Daily Telegraph. 11 November 1918.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 291.

- ↑ "People associated with HMS Royal Oak". scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Wrecks.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 290.

- ↑ "Wreck of HMS Royal Oak". scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Wrecks.

- ↑ Arlidge, John (18 February 2001), "New battle engulfs Royal Oak", The Observer

- ↑ Royal Oak Oil Removal Programme, Briggs Marine, retrieved 27 January 2012

- ↑ "Technology gives new view of HMS Royal Oak" (PDF), DLO News, Defence Logistics Organisation, August 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-13

- ↑ Rohwer 2005, p. 31.

- 1 2 Grant 2008, p. 302.

- 1 2 3 4 Whitley 1998, p. 44.

- ↑ Gardiner 1979, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 384.

- ↑ Hore 2006, p. 89.

- ↑ Sondhaus 2014, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ "Idaho". Naval History & Heritage Command. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 246.

- ↑ Grant 2008, pp. 282–83.

- 1 2 Ballard 1990, p. 221.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 324.

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2003, pp. 413–14.

- 1 2 3 4 McLaughlin 2003, p. 402.

- 1 2 Burt 2012, p. 135.

- ↑ Rohwer 2005, p. 118.

- ↑ Admiralty Historical Section, pp. 201–02.

- 1 2 DANFS Arizona.

- ↑ "Pearl Harbor Raid, 7 December 1941, USS Arizona during the Pearl Harbor Attack". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ Stillwell 1991, p. 279.

- ↑ Wright 2002, pp. 78, 80.

- ↑ "Arizona, USS (battleship) (shipwreck)". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ↑ "U.S.S. Arizona Bell". University of Arizona. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ↑ DANFS Nevada.

- ↑ "Flagship of the Fleet: Life and Death of the USS Arizona". Current Exhibits. Arizona Capitol Museum. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- 1 2 3 DANFS Utah.

- ↑ National Park Service. "USS Arizona Memorial: Submerged Cultural Resources Study (Chapter 2)". Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Pearl Harbor Area Attractions". Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "USS Utah – The 100th Anniversary". Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Chesneau 1980, p. 13.

- ↑ Garzke, William; Dulin, Robert; Denlay, Kevin. "Death of a Battleship: A Reanalysis of the Tragic Loss of HMS Prince of Wales" (PDF). Pacific Wrecks. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 Julian Ryall, Tokyo; Joel Gunter (25 October 2014). "Celebrated British warships being stripped bare for scrap metal". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander & Cundall, Peter (2013). "IJN Subchaser CH-9: Tabular Record of Movement". Kusentei!. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 Hackett, Bob & Kingsepp, Sander (2010). "IJN Repair Ship Asahi: Tabular Record of Movement". Kido Butai. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ↑ Mattesini 2002, pp. 529–30.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, pp. 404, 428.

- ↑ "Divers locate wreck of battleships sunk on way to Malta". Times of Malta. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Combined Fleet – tabular history of Hiei". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- 1 2 Grant 2008, p. 318.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Stille 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Lundgren, Robert. DiGiulian, Tony, ed. "Kirishima Damage Analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 176.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 165.

- 1 2 Grant 2008, p. 281.

- ↑ Williamson 2003, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 Jordan & Dumas 2009, p. 93.

- ↑ Le Masson 1969, p. 65.

- 1 2 Whitley 1998, p. 36.

- ↑ Dumas 1985, p. 231.

- ↑ Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander. "IJN Battleship MUSASHI: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Imperial Battleships.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 322.

- ↑ Patricia Denise Chiu (March 3, 2015). "Explorers find 'most famous' Japanese WWII battleship off Romblon's Sibuyan Island". GMA News.

- ↑ "Microsoft's Allen Says WWII Battleship Musashi Found". The Japan Times. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Mari (13 March 2015). "Japanese WWII battleship Musashi Exploded Under Water, New Footage Suggests". StarTribune. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett; Sander Kingsepp; Allyn Nevitt. "Fuso Tabular record of movements". Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Combinedfleet.com.

- ↑ Tully 2009, p. 21.

- 1 2 Grant 2008, p. 323.

- ↑ Tully, Anthony P. (9 May 2001). "Important Announcement: Dives at Surigao Strait". A.P. Tully Message Board. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 273.

- ↑ Breyer 1989, p. 26.

- 1 2 Gröner 1990, p. 35.

- 1 2 Williamson 2003, p. 40.

- ↑ Zetterling & Tamelander 2009, p. 327.

- ↑ Sweetman 2004, p. 248.

- ↑ Hafsten 1991, p. 221.

- 1 2 Wheeler 1980, p. 183.

- ↑ Stille 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Stille 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Cernuschi & O'Hara 2010, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Cernuschi & O'Hara 2010, pp. 81–85, 88.

- ↑ Brescia 2012, p. 59.

- ↑ Grant 2008, p. 327.

- 1 2 "Remains of sunken Japanese battleship Yamato discovered". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. 4 August 1985. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ Yohei Izumida (May 8, 2016). "Kure to embark on underwater survey of mighty Yamato warship". Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ Yohei Izumida (July 17, 2016). "New footage of sunken Yamato given to media before showing". Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Outline". Hiroshima, Japan: Yamato Museum. 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "Yamato—Kure Maritime Museum Leaflet" (PDF). Hiroshima, Japan: Yamato Museum. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander. "IJN SETTSU: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Combined Fleet.

- 1 2 3 4 Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander; Ahlberg, Lars. "IJN ISE: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Combined Fleet.

- 1 2 3 4 Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander. "IJN HYUGA: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Combined Fleet.

- 1 2 3 Smith 1995, p. 189.

- 1 2 3 Tully, Anthony P. (2001). "IJN Shinano: Tabular Record of Movement". Kido Butai. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Daily Star, 4 September 2004.

- ↑ Taras 2000, p. 27.

- ↑ Balakin 2004, p. 39.

- 1 2 Vinogradov 2011, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Forczyk 2009, p. 46–47.

- 1 2 Forczyk 2009, p. 46.

- ↑ Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, p. 18.

- ↑ Warner & Warner 2002, pp. 279–82.

- 1 2 Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Burt 1988, p. 205.

- ↑ Burt 1988, p. 206.

- 1 2 Hearst 1911, p. 651.

- 1 2 Gardiner 1979, p. 297.

- ↑ Chiles 2011, p. 133.

- 1 2 Jellicoe 1919, p. 141.

- 1 2 "HMS Audacious". Deep image underwater shipwreck exploring. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ↑ Bishop, Leigh. "Sheer Scale of a Sleeping Dreadnought". Divernet. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ Brown 2003, p. 161.

- ↑ Jellicoe 1919, pp. 143–44.

- 1 2 3 4 Para 2015, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Burt 1988, pp. 156, 174.

- 1 2 Gardiner 1979, p. 295.

- ↑ Gardiner 1979, p. 294.

- 1 2 3 Hocking 1990, p. 79.

- ↑ "Le "due vite" della nave da battaglia Benedetto Brin" [The "Two Lives" of the Battleship Benedetto Brin] (in Italian). Ministero Della Difesa. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 Burt 1988, pp. 247–48.

- ↑ Burt 1988, pp. 249, 251.

- 1 2 3 4 Burt 1988, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 4 Chesneau 1979, p. 9.

- 1 2 Whitley 1998, pp. 157–58.

- 1 2 Preston 1972, p. 176.

- ↑ Giorgerini 1980, pp. 272, 277.

- ↑ Allen 1964, pp. 23–26.

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2003, pp. 242, 306–07.

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2003, p. 306.

- 1 2 3 McLaughlin 2003, pp. 242, 310.

- ↑ Hocking 1990, p. 583.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 343.

- 1 2 Ruberti, Fabio. "Regina Margherita" (PDF). iantexpeditions.com. IANTD Expedditions. Retrieved 14 September 2005.

- ↑ Lengerer 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ McLaughlin (September 2008), pp. 47, 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Preston 1972, p. 207.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 115.

- ↑ "People associated with HMS Vanguard". scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Wrecks.

- 1 2 3 4 "History of HMS Vanguard". scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Wrecks.

- ↑ Lengerer 2006, pp. 66–84.

- ↑ Kingsepp 2007, pp. 99–100.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 239.

- 1 2 3 Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, p. 24.

- 1 2 Lengerer 2006, pp. 83–84.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burt 1988, p. 133.

- 1 2 3 4 New York Times, 27 August 1922.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fernández & March 2007, p. 106.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 378.

- 1 2 3 Proceedings 1940, p. 813.

- ↑ Roskill 1976, p. 381.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 376.

- ↑ Platón 2001, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 4 Slavick 2003, p. 233.

- 1 2 Gröner 1990, p. 22.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Williams 2009, pp. 129–32.

- ↑ Williams 2009, pp. 140–41.

- 1 2 3 Newell 1957, pp. 39, 42.

- ↑ DANFS Oklahoma.

- 1 2 Whitley 1998, p. 29.

- 1 2 "Planes Fail to Find Warship Lost at Sea," Chicago Daily Tribune, 11 November 1951, 27.

- ↑ de Oliveira Ribeiro, Paulo. "Os Dreadnoughts da Marinha do Brasil: Minas Geraes e São Paulo". Poder Naval Online. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- ↑ "Lost Warship Hunt Given Up," Los Angeles Times, 11 December 1951, 13.

- ↑ Whitley 1998, p. 162.

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2003, pp. 419, 422.

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2003, p. 423.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2007, pp. 142–52.

- ↑ Greene & Massignani 2004, pp. 195–98.

- 1 2 Balakin 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ Forczyk 2009, p. 47.

- 1 2 Burt 1988, p. 90.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 192.

- ↑ Staff 2008, p. 116.

- 1 2 Staff 2008, pp. 116–17.

- ↑ Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 294.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 228.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 242.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gröner 1990, p. 28.

- ↑ "SMS König 3D Shipwreck". scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Wrecks.

- ↑ MacDonald 1998, p. 73–75.

- 1 2 3 Staff 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ "SMS Kronprinz 3D Shipwreck". scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Wrecks.

- 1 2 3 Staff 2010, p. 36.

- ↑ "SMS Markgraf 3D Shipwreck". scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Wrecks.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Gröner 1990, p. 26.

- ↑ "Bristol garden's WW1 German battleship bell sells for £5,000". BBC News Online. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Gröner 1990, p. 30.

- 1 2 Melnikov 2006, p. 47.

- ↑ Yolkin, A. "Kladbische korablei (Кладбище кораблей)". www.wreck.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 Whitley 1998, p. 52.

- 1 2 Lenton 1998, p. 574.

- ↑ "The Mansion House". Staffordshire County Council. n.d. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Whitley 1998, p. 38.

- ↑ Schultz 1992, pp. 228–48.

- ↑ Williamson 2003, p. 6.

- ↑ "The battleship that started World War Two". Diver. May 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 4 Gröner 1990, p. 32.

- ↑ Breyer 1990, p. 34.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 150.

- ↑ Williamson 2003, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Gröner 1990, p. 17.

- ↑ DANFS Texas.

- 1 2 Allen 1993, p. 250.

- ↑ Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 48.

- 1 2 Brown 1997, pp. 176–77.

- ↑ "HMS Empress of India Wreck in Lyme Bay". Teign Dive. Teign Diving Centre. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2003, pp. 44–45.

- 1 2 3 DANFS Indiana.

- ↑ DANFS Massachusetts.

- 1 2 "USS Massachusetts learn about the history audio transcript" (PDF). Florida's "Museums in the Sea". Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- 1 2 "The Naval Bombing Experiments: Bombing Operations". Naval History & Heritage Command. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 Schleihauf 2007, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 DANFS Alabama.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 334.

- 1 2 3 DANFS Iowa.

- ↑ "USS Iowa (Battleship # 4), 1897–1923. Later renamed Coast Battleship # 4". Department of the Navy — Naval Historical Center. 13 April 2003. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- 1 2 Wildenberg 2014, p. 114.

- 1 2 DANFS Virginia.

- 1 2 Lengerer (September 2008), p. 59.

- ↑ McLaughlin 2000, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 Lengerer (September 2008) 2.

- 1 2 Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, p. 23.

- 1 2 London Times, 22 January 1925.

- 1 2 Brown 2006, p. 22.

- ↑ Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 32.

- ↑ Ireland 1996, pp. 186–87.

- 1 2 Delgado & Murphy 1991.

- ↑ Ireland 1996, pp. 186-87.

- 1 2 Tully, A.P. (2003). "Nagato's Last Year: July 1945 – July 1946". Mysteries/Untold Sagas of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ London Times, 3 March 2007.

- ↑ "Bikini Atoll Dive Tourism Information". Bikini Atoll Divers. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 DANFS Pennsylvania.

- 1 2 3 Banks 2002, p. 38.

- 1 2 Friedman 1985, p. 420.

- ↑ Bonner 1996, p. 108.

References

- Admiralty Historical Section (2002). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean: November 1940 – December 1941. Whitehall Histories, Naval Staff Histories. 2. Whitehall History in association with Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5205-9.

- Balakin, Sergei (2004). Морские сражения русско-японской войны 1904–1905 [Naval Battles of the Russo-Japanese War] (in Russian). Morskaya Kollektsya (Maritime Collection). LCCN 2005429592.

- Ballard, Robert D. (1990). Bismarck: Germany's Greatest Battleship Gives Up its Secrets. Madison Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7858-2205-9.

- Banks, Herbert C. (ed.) (2002). USS New York (BB-34): The Old Lady of the Sea. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56311-809-8.

- Bogdanov, M. A. (2004). Eskadrenny bronenosets Sissoi Veliky (Эскадренный броненосец "Сисой Великий"). Stapel Series (in Russian). Vol. 1. M. A. Leonov. ISBN 5-902236-12-6.

- Bonner, Kermit (1996). Final Voyages. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56311-289-8.

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8.

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battlecruisers of the World, 1905–1970. Macdonald/Jane's. ISBN 0-356-04191-3.

- Breyer, Siegfried (1989). Battleship "Tirpitz". Schiffer Pub. ISBN 978-0-88740-184-8.

- Breyer, Siegfried (1990). The German Battleship Gneisenau. Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88740-290-6.

- Brown, David K. (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. Chatham. ISBN 1-86176-022-1.

- Brown, David K. (2003). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922 (reprint of the 1999 ed.). Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-531-4.

- Brown, David Keith (2006) [2000]. Nelson to Vanguard: Warship Design and Development, 1923–1945. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-602-5.

- Burt, R. A (1988). British Battleships 1889–1904. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-061-0.

- Burt, R. A. (2012). British Battleships, 1919–1939 (2nd ed.). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-052-8.

- Campbell, N.J.M. (1978). Preston, Antony, ed. The Battle of Tsu-Shima, Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4. II. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87021-976-6.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Caresse, Philippe (2010). "The Drama of the Battleship Suffren". In Jordan, John. Warship 2010. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1.

- Caresse, Phillippe (2012). "The Battleship Gaulois". In Jordan, John. Warship 2012. Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-156-9.

- Cernuschi, Enrico; O'Hara, Vincent P. (2010). "Taranto: The Raid and the Aftermath". In Jordan, John. Warship 2010. Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1.

- Chesneau, Roger (1979). Kolesnik, Eugene, ed. Conway's All The World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Chiles, James R. (2011). Inviting Disaster: Lessons From the Edge of Technology. Harper Business. ISBN 0-06-662082-1.

- Delgado, James P.; Murphy, Larry E. (1991). "Chapter 4: Site Descriptions". The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb. nps.gov. National Park Service. ASIN B0014H9NEW. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- Dumas, Robert (1985). "The French Dreadnoughts: The 23,500 ton Courbet Class". In John Roberts. Warship. IX. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-984-7. OCLC 26058427.

- Evans, David; Peattie, Mark (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-715-1. OCLC 12214729.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1922. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8. OCLC 12119866.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Grant, R.G. (18 August 2008). Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7566-3973-0.

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (2004). The Black Prince and the Sea Devils: The Story of Valerio Borghese and the Elite Units of the Decima MAS. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81311-4.

- Giorgerini, Giorgio (1980). "The Cavour & Duilio Class Battleships". In Roberts, John. Warship IV. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-205-6.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6. OCLC 22101769.

- Hafsten, Bjørn (1991). Flyalarm: Luftkrigen over Norge 1939–1945. Sem & Stenersen. ISBN 82-7046-058-3.

- Herwig, Holger (1980). "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hocking, Charles (1990). Dictionary of Disasters at Sea During The Age of Steam. The London Stamp Exchange. ISBN 0-948130-68-7.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads: An Illustrated History of Battleships From 1860 to the First World War. Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- Ireland, Bernard (1996). Jane's Battleships of the 20th Century. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-470997-0.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Jones, Geoffrey P. (1979). Battleship Barham. William Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0416-0.

- Jordan, John; Dumas, Robert. French battleships 1922–1956. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-034-5.

- Langensiepen, Bernd; Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-610-1.

- Le Masson, Henri (1969). The French Navy 1. Navies of the Second World War. Doubleday.

- Lenton, H. T. (1998). British & Empire Warships of the Second World War. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-048-7.

- MacDonald, Rod (1998). Dive Scapa Flow. Mainstream. ISBN 978-1-85158-983-8.

- Mattesini, Francesco (2002). La Marina e l'8 settembre. Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare. OCLC 61487486.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2000). Preston, Anthony, ed. The Retvizan: An American Battleship for the Czar. Warship. 2000–2001. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-791-0.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2003). Russian & Soviet Battleships. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-481-4.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2007). Jordan, John, ed. The Loss of the Battleship Novorossiisk. Warship 2007. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-84486-041-8.

- Melnikov, R. M (2006). Eskadrenny bronenosets "Rostislav" (1893–1920) (Эскадренный броненосец "Ростислав" (1893–1920)) (in Russian). M. A. Leonov. ISBN 5-902236-34-7.

- Newell, Gordon (1957). Pacific Tugboats. Superior Publishing.

- Para, Andy (23 September 2015). Call the Hands. Lulu.com. ISBN 1326409298.

- Platón, Miguel (2001). Hablan los militares: testimonios para la historia, 1939-1996. Planeta. ISBN 84-08-03783-8.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Reilly, John C.; Scheina, Robert L. (1980). American Battleships 1896–1923: Predreadnought Design and Construction. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-524-7.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Roskill, Stephen (1976). Naval Policy Between the Wars, Volume 1. Collins. ISBN 0-00-211561-1.

- Schleihauf, William (2007). "The Baden Trials". In Preston, Anthony. Warship 2007. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84486-041-8.

- Schultz, Willi (1992). Linienschiff Schleswig-Holstein: Flottendienst in drei Marinen. Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. ISBN 3-7822-0502-2.

- Slavick, Joseph P. (2003). The Cruise of the German Raider Atlantis. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-537-8.

- Smith, Peter C. (1995). Eagle's War: War Diary of an Aircraft Carrier. Crécy Books. ISBN 0-947554-60-2.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2014). The Great War at Sea: A Naval History of the First World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107036901.

- Staff, Gary (2008). Battle for the Baltic Islands 1917: Triumph of the Imperial German Navy. Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-787-7.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918 (1). Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Stille, Mark (2008). Imperial Japanese Navy Battleship 1941–1945. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-280-6.

- Stillwell, Paul (1991). Battleship Arizona: An Illustrated History. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-023-8. OCLC 2365447.

- Sweetman, John (2004). Tirpitz: Hunting the Beast. Sutton Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-7509-3755-9.

- Taras, Alexander (2000). Корабли Российского императорского флота 1892–1917 гг [Ships of the Imperial Russian Navy 1892–1917]. Library of Military History (in Russian). Kharvest. ISBN 978-985-433-888-0.

- Tully, Anthony P. (2009). Battle of Surigao Strait. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35242-2.

- Vinogradov, Sergei; Fedechkin, Aleksei (2011). Bronenosnyi kreyser "Bayan" i yego potomki. Od Port-Artura do Moonzunda [Armoured cruiser "Bayan" and her offspring. From Port Artur to Moonsund.] (in Russian). Yauza / EKSMO. ISBN 978-5-699-51559-2.

- Warner, Denis; Warner, Peggy (2002). The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905 (2nd ed.). Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.

- Wheeler, Keith (1980). War Under the Pacific. Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-3376-1.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-184-X.

- Wildenberg, Thomas (2014). Billy Mitchell's War with the Navy: The Army Air Corps and the Challenge to Seapower. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781612513324.

- Williams, Mike (2009). Jordan, John, ed. Mutsu – An Exploration of the Circumstances Surrounding Her Loss. Warship 2009. Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-089-0.

- Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Battleships 1939–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-498-6.

- Zetterling, Niklas; Tamelander, Michael (2009). Tirpitz: The Life and Death of Germany's Last Super Battleship. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-18-7.

Journals

- Allen, M. J. (1964). "The Loss & Salvage of the "Leonardo da Vinci"". Warship International. Naval Records Club. I (Reprint).

- Allen, Francis J. (1993). ""Old Hoodoo": The Story of the U.S.S. Texas". Warship International. International Naval Research Organization. XXX (3). ISSN 0043-0374.

- Fernández, Rafael; Mitiukov, Nicholas; Crawford, Kent (March 2007). "The Spanish Dreadnoughts of the España class". Warship International. International Naval Research Organization. 44 (1): 106. ISSN 0043-0374. OCLC 1647131.

- Magazines, Hearst (November 1911). "French Battleship Blown up in Toulon Harbor". Popular Mechanics.

- Kingsepp, Sander (March 2007). Ahlberg, Lars, ed. "Reader Reactions and Questions". Contributions to the History of Imperial Japanese Warships (Paper II). (subscription required)

- Lengerer, Hans (September 2006). Ahlberg, Lars, ed. "Battleships Kawachi and Settsu". Contributions to the History of Imperial Japanese Warships (Paper I). (subscription required)

- Lengerer, Hans (September 2008). Ahlberg, Lars, ed. "Tango (ex-Poltava)". Contributions to the History of Imperial Japanese Warships (Paper V).

(subscription required)(contact the editor at lars.ahlberg

- Lengerer, Hans (September 2008). Ahlberg, Lars, ed. "Hizen (ex-Retvizan)". Contributions to the History of Imperial Japanese Warships (Paper V). (subscription required)

- Lengerer, Hans (September 2008). Ahlberg, Lars, ed. "Sagami (ex-Peresvet) and Suwō (ex-Pobeda)". Contributions to the History of Imperial Japanese Warships (Paper V). (subscription required)(contact the editor at lars.ahlberg@halmstad.mail.postnet.se for subscription information)

- McLaughlin, Stephen (September 2008). Ahlberg, Lars, ed. "Peresvet and Pobéda". Contributions to the History of Imperial Japanese Warships (Paper V). (subscription required)

- "Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute". 66. United States Naval Institute. 1940.

- Sieche, Erwin F. (1991). "S.M.S. Szent István: Hungaria's Only and Ill-Fated Dreadnought". Warship International. International Warship Research Organization. XXVII (2). ISSN 0043-0374.

- Wright, Christopher C., ed. (Mar 2002). "The US Navy's Study of the Loss of the Battleship Arizona". Warship International. International Naval Research Organization. XXXIX–XL (3–4, 1). ISSN 0043-0374.

Online resources

- Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander. "Combined Fleet". combinedfleet.com.

- "Alabama II (Battleship No. 8)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- "Arizona". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command (NH&HC). 9 November 2004. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "Indiana". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 14 March 2004. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Iowa". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Massachusetts". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Nevada". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "Oklahoma". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Texas". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Utah". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- "Virginia". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "Pennsylvania". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

News publications

- Blanford, Nicholas (4 September 2004). "Divers discover British ship wreck after 111 years". The Daily Star. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- "The Sinking of H.M.S. Monarch" (43866). The Times. 22 January 1925. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Ecott, Tim (3 March 2007). "World's best wreck diving". The Times. Retrieved 11 September 2009. (subscription required)

- "French Battleship wrecked, 3 men lost". New York Times. 27 August 1922. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

_sinking_1921.jpg)

_-_NH_52583.jpg)

_underway_c1922.jpg)

_after_aireal_bombing_test.jpg)

_in_November_1944.jpg)

_sinking_off_Kwajalein03_1948.jpg)

_aground_and_burning_off_Waipio_Point%2C_after_the_end_of_the_Japanese_air_raid..jpg)